Global Top E-Commerce Companies: Transparency Analysis Based on Annual Reports

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- The board, the CEO and the audit committee (Klein 2002; Brennan 2006; Christopher 2010; Allegrini and Greco 2011; Cucari et al. 2017; Kolev et al. 2019);

- Implications of corporate governance on company performance (Erhardt et al. 2003; Bauer et al. 2004; Renders et al. 2010);

- Relationships between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Arora and Dharwadkar 2011; Simpson and Taylor 2013; Pucheta-Martínez and Gallego-Álvarez 2019; Naciti et al. 2022);

- Corporate governance and information disclosure (Tiron Tudor 2006; Bauwhede and Willekens 2008; Roychowdhury et al. 2019).

3. Methods

- -

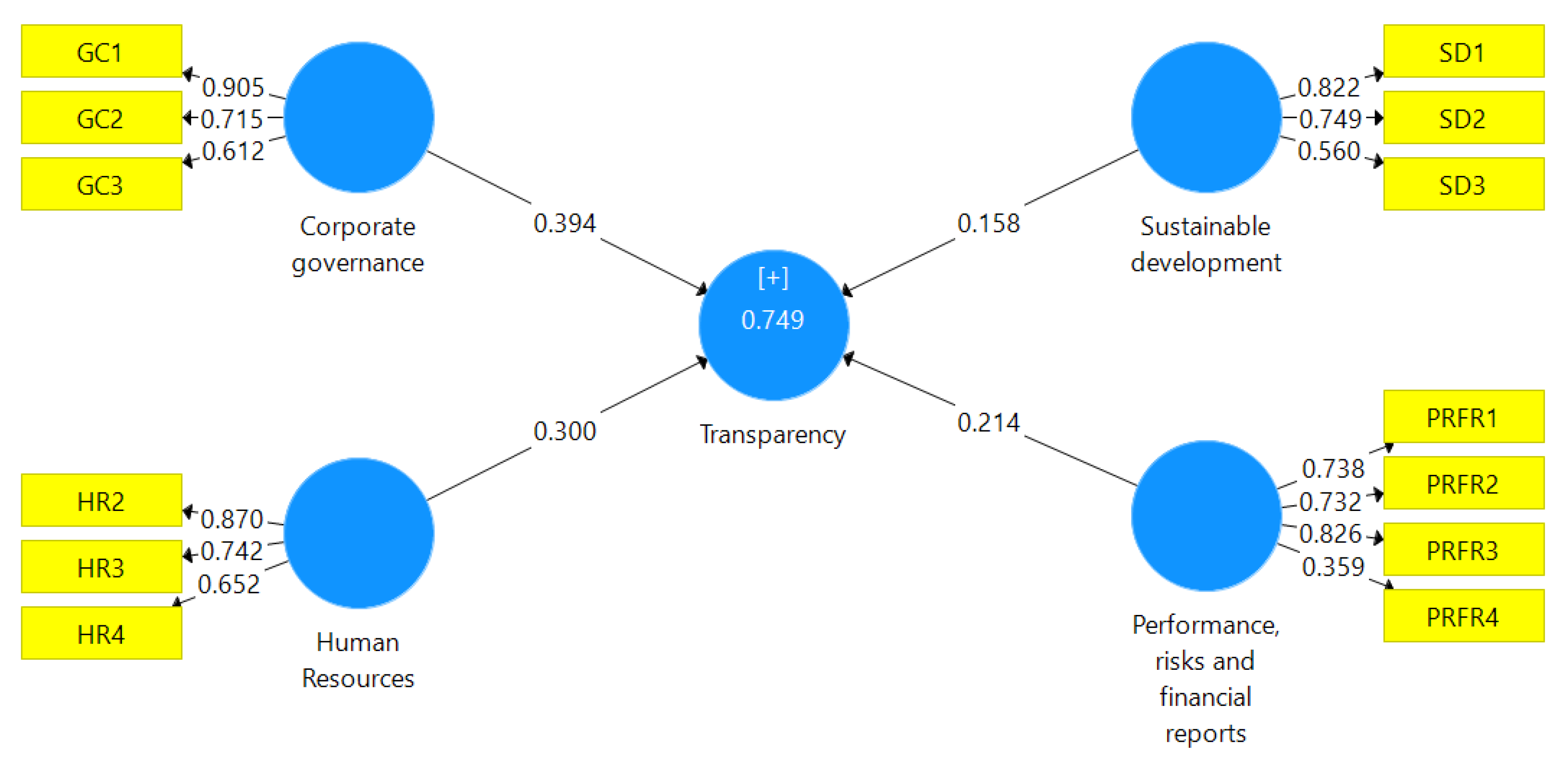

- H1: the structure of corporate governance has a significant influence on company transparency;

- -

- H2: the content of human resource policies has a positive impact on the level of company transparency;

- -

- H3: there is a direct proportional ratio between the degree of company transparency and sustainable development policies;

- -

- H4: the accounting and risk management policies, as well as the system of performance appraisal, have a significant impact on company transparency in its decision-making process.

4. Results

5. Discussion

- 40–250 (Xplora Tech AS, Delticom, Smartphoto Group)—10%;

- 250–5000 (Alumex PLC, Cnova, Rakuten, Wix)—13%;

- 5000–50,000 (Shopify, Pinduoduo, Prosus, Ebay, Zalando, Smurfit Kappa Gp, Otto Group)—23%;

- 50,000–500,000 (Meituan, Best buy, Apple, Alibaba Group Holding Limited, Costco, Jingdon, Target, Kroger)—26%;

- 500,000–2,200,000 (BigCommerce, Amazon, Walmart)—10%.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | E-Commerce Company Name |

|---|---|

| 1. | Alibaba Gr. Holding Ltd. |

| 2. | Alumex PLC |

| 3. | Amazon |

| 4. | Apple |

| 5. | Best buy |

| 6. | BigCommerce |

| 7. | Costco |

| 8. | Cnova |

| 9. | Delticom |

| 10. | Ebay |

| 11. | Home Depot |

| 12. | Jingdon |

| 13. | Just Eat Takeaway |

| 14. | Kroger |

| 15. | Meituan |

| 16. | Otto Group |

| 17. | Pinduoduo |

| 18. | Prosus |

| 19. | Rakuten |

| 20. | Showroomprive |

| 21. | Shopify |

| 22. | Smartphoto Group |

| 23. | Smurfit Kappa Gp |

| 24. | Suning |

| 25. | Target |

| 26. | Walmart |

| 27. | Wayfair |

| 28. | Weebly |

| 29. | WIX |

| 30. | Xplora |

| 31. | Zalando |

References

- Abdel-Maksoud, Ahmed, David Dugdale, and Robert G. Luther. 2005. Non-financial performance measurement in manufacturing companies. The British Accounting Review 37: 261–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, Indra, and James Guthrie. 2004. Human capital reporting in a developing nation. The British Accounting Review 36: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexopoulos, Ilias, Kostas Kounetas, and Dimitris Tzelepis. 2018. Environmental and Financial Performance. Is there a win-win or a win-loss situation? Evidence from the Greek manufacturing. Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1275–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allegrini, Marco, and Giulio Greco. 2011. Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Journal of Management & Governance 17: 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ansoff, H. Igor, Daniel Kipley, Alfred O. Lewis, Roxanne Stevens, and Rick Ansoff. 2019. Implanting Strategic Management, 3rd ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, Güler, Aslı Aybars, and Ozlem Kutl. 2010. Managing corporate performance: Investigating the relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance in emerging markets. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 59: 229–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Glen, and Deborah Lewis. 2019. Corporate Financial Management, 6th ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, Punit, and Ravi Dharwadkar. 2011. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Moderating Roles of Attainment Discrepancy and Organization Slack. Corporate Governance: An International Review 19: 136–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar-Diez, Elisa, María D. Odriozola, and José Luis Fernández Sánchez. 2015. Transparency through European corporate governance codes. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 13: 244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkemeyer, Ralf, Breeda Comyns, Frank Figge, and Giulio Napolitano. 2014. CEO statements in sustainability reports: Substantive information or background noise? Accounting Forum 38: 241–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Rob, Nadja Guenster, and Rogér Otten. 2004. Otten Empirical evidence on corporate governance in Europe: The effect on stock returns, firm value and performance. Journal of Asset Management 5: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauwhede, Heidi Vander, and Marleen Willekens. 2008. Disclosure on Corporate Governance in the European Union. Corporate Governance: An International Review 16: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuren, Ilse Maria, Nelson Hein, and Roberto Carlos Klann. 2008. Impact of the IFRS and US-GAAP on economic-financial indicators. Managerial Auditing Journal 23: 632–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Gauri, Ole-Kristian Hope, and Tony Kang. 2006. Does corporate governance transparency affect the accuracy of analyst forecasts? Accounting and Finance 46: 715–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birca, Alic. 2018. Organizations involvement in the sustainable development of human resources. Annals of the ‘Constantin Brancusi’ University of Targu Jiu. Economy Series. pp. 14–24. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/cbujrnlec/y_3a2018_3av_3aspecial_3ap_3a14-24.htm (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Bold, Frank. 2017. Compliance and Reporting under the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive: Requirements and Opportunities. Brussels and Brno: Frank Bold Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, Marianne, Julia B. Earp, D. Scott Showalter, and Paul F. Williams. 2017. Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Stakeholder Concerns: Is There a Disconnect? Accounting Horizons 31: 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, Matthias, and Sascha Schmidt. 2008. Defining the strategic role of boards and measuring boards’ effectiveness in strategy implementation. Corporate Governance 8: 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Niamh. 2006. Boards of directors and firm performance: Is there an expectations gap? Corporate Governance: An International Review 14: 577–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, Eugene F., and Phillip R. Daves. 2007. Intermediate Financial Management, 9th ed. Belmont: Thomson Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Burhan, Annisa Hayatun N., and Wiwin Rahmanti. 2012. The impact of sustainable reporting on company’s performance. Journal of Economics Business and Accountancy Ventura 15: 257–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes-Lorente, José, Jerónimo Burgos-Jiménez, and María José Álvarez Gil. 2004. Stakeholders’ environmental influence. An empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry. Scandinavian Journal of Management 19: 333–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, Tzu-Kuan, and Yi-Hsin Wang. 2015. Determinants of social disclosure quality in Taiwan: An application of Stakeholder Theory. Journal of Business Ethics 129: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Frederick D. S., and Gerhard G. Mueller. 1992. International Accounting, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 610p. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, Joe. 2010. Corporate governance—A multi-theoretical approach to recognizing the wider influencing forces impacting on organizations. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 21: 683–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, Philip L., and Robert A. Wood. 1984. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance. The Academy of Management Journal 27: 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cucari, Nicola, Salvatore Esposito de Falco, and Beatrice Orlando. 2017. Diversity of Board of Directors and Environmental Social Governance: Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 250–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Burgos-Jiménez, Jerónimo, Diego Alfonso Vazquez-Brust, J. A. Plaza-Úbeda, and Jeroen Dijkshoorn. 2013. Environmental protection and financial performance: An empirical analysis in Wales. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 33: 981–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, Thomas, and Kai Hockerts. 2002. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment 11: 130–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, David. 2010. Financial statement and investment decision. International Journal of Business and Commerce 3: 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, James B. 2016. Modern Gross Profit Analysis. The Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 27: 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljelly, Abuzar M. A. 2004. Liquidity-profitability tradeoff: An empirical investigation in an emerging market. International Journal of Commerce and Management 14: 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, Khaled, and David Paton. 2009. The impact of financial performance on evironmental policy: Does firm life cycle matter? Business Strategy and the Environment 18: 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, Niclas L., James D. Werbel, and Charles B. Shrader. 2003. Board of Director Diversity and Firm Financial Performance. Corporate Governance 11: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EU/European Union. 2014. Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Text with EEA relevance, L 330. Bruxelles: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Feleagă, Niculae, Liliana Feleagă, Voicu Dan Dragomir, and Adrian Doru Bigioi. 2011. Guvernanţa corporativă în economiile emergente: Cazul României. Economie teoretică şi aplicată 18: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Kiran Jude, Vinesh Raja, and Andrew Whalley. 2006. Lessons from implementing the balanced scorecard in a small and medium size manufacturing organization. Technovation 26: 623–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, Belen, Silvia Romero, and Silvia Ruiz. 2014. Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. Journal of Business Ethics 122: 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegener, Mark K. 2005. Determinants of board participation in the strategic decisions of small corporations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29: 627–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Roger H. 1988. Outside directors and the privately-owned firm: Are they necessary? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 13: 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Jennifer, Allen H. Huang, Shivaram Rajgopal, and Amy Y. Zang. 2008. CEO Reputation and Earnings Quality. Contemporary Accounting Research 25: 109–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, Rosemary R., and William F. Wempe. 2009. Lean manufacturing, non-financial performance measures, and financial performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 29: 214–40. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer, Olivier, Howard Thomas, and Anna Goussevskaia. 2008. The structure and evolution of the strategic management field: A content analysis of 26 years of strategic management research. International Journal of Management Reviews 10: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Huiqi, Myung S. Park, and Sang Hyun Suh. 2020. Non-financial performance measures, CEO compensation, and firms’ future value. Journal of Business Research 110: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, Katarzyna. 2016. Financial Liquidity and Profitability Management in Practice of Polish Business. In Financial Environment and Business Development. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics. Cham: Springer, pp. 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goram, Paul J., Theodore Mock, and Gary S. Monroe. 2011. Financial analysts’ evaluation oh enhanced disclosure of non-financial performance indicators. The British Accounting Review 43: 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, Hugh, Maclyn Clouse, and Tracy Xu. 2021. Human resource reporting: Implications for corporate governance. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review 5: 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2013. Editorial—Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Planning 46: 1–12. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2233795 (accessed on 27 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hategan, Camelia-Daniela, Nicoleta Sirghi, Ruxandra-Ioana Curea-Pitorac, and Vasile-Petru Hategan. 2018. Doing well or doing good: The relationship between corporate social responsibility and profit in Romanian companies. Sustainability 10: 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helfat, Constance E., and Jeffrey A. Martin. 2015. Dynamic Managerial Capabilities: Review and Assessment of Managerial Impact on Strategic Change. Journal of Management 41: 1281–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, Christian, and Stefan Schaltegger. 2006. Corporate Sustainability Reporting. An Overview. In Sustainability Accounting and Reporting. Edited by Stefan Schaltegger, Martin Bennett and Roger Burritt. Dordrecht: Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-4079-5/978-1-4020-4974-3. [Google Scholar]

- IFAC/International Federation of Accountants. 2021. COP26 Key Takeaways for Business and Accountants. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/contributing-global-economy/discussion/climate-summit-spotlights-business-and-accountants (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- IFRS/International Financial Reporting Standards. 2001. The #1 Website for Global Accounting News. Available online: https://www.iasplus.com/en/standards/ifrs/ifrs1 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Iwata, Hiroki, and Keisuke Okada. 2011. How does environmental performance affect financial performance? Evidence from Japanese manufacturing firms. Ecological Economics 70: 1691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janning, Finn, Wafa Khlif, and Coral Ingley. 2020. The Illusion of Transparency in Corporate Governance. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, ISBN 978-3-030-35779-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Stewart, Geoff Frost, Janice Loftus, and Sandra Lee Van der Laan. 2007. An empirical examination of the market returns and financial performance of entities engaged in sustainability reporting. Australian Accounting Review 17: 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2006. How to implement a new strategy without disrupting your organization. Harvard Business Review 84: 100–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Md Habib-Uz-Zaman, and Rashidozzaman Khan. 2010. Human capital disclosure practices of top Bangladeshi companies. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting 14: 329–49. [Google Scholar]

- King, Andrew. 2007. Cooperation between corporations and environmental groups: A transaction cost perspective. The Academy of Management Review 32: 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, April. 2002. Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33: 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolev, Kalin, David B. Wangrow, Vincent L. Barker, and Donald J. Schepker. 2019. Board Committees in Corporate Governance: A Cross-Disciplinary Review and Agenda for the Future. Journal of Management Studies 56: 1138–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasher, William R. 2014. Practical Financial Management, 8th ed. Boston: CENGAGE Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Mengge, and Jinxin Yang. 2019. Effects of CEO duality and tenure on innovation. Journal of Strategy and Management 12: 536–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, Jan-Bernd. 1989. Latent Variable Path Modelling with Partial Least Squares. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- López-Arceiz, Francisco José, Ana José Bellostas-Pérezgrueso, José Mariano Moneva-Abadía, and María Pilar Rivera-Torres. 2017. The role of corporate governance and transparency in the generation of financial performance in socially responsible companies. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad 47: 44–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, Giacomo, and Simone Toccafondi. 2012. The role of stakeholders in sustainability reporting assurance. Journal of Business Ethics 107: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, Martin, Ronan McIvor, Raymond Treacy, and Tony Wall. 2018. A study of human capital reporting in the United Kingdom. Accounting Forum 42: 130–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, Abagail, and Donald Siegel. 2000. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal 21: 603–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, Jose M., and Eduardo Ortas. 2010. Corporate environmental and financial performance: A multivariate approach. Industrial Management & Data Systems 110: 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Naciti, Valeria, Fabrizio Cesaroni, and Luisa Pulejo. 2022. Corporate governance and sustainability: A review of the existing literature. Journal of Management and Governance 26: 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Yuriko, Akihiro Amano, Kanichiro Matsumura, Kiminori Genba, and Makiko Nakano. 2006. Relationship between environmental performance and financial performance: An empirical analysis of japanese corporations. Business Strategies and the Environment 16: 106–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needles, Belverd E., and Marian Powers. 2007. Financial Accounting, 9th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Anne Ellerup, and Christa Thomsen. 2007. Reporting CSR: What and how to say it? Corporate Communications: An International Journal 12: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2004. Principles of Corporate Governance. Paris: OECD Publications Service. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2015. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, Mohamed A., Ashraf Khallaf, Kimberly C. Gleason, and Tahat Yasean Tahat. 2020. Non-financial performance measures disclosure, quality strategy, and organizational financial performance: A mediating model. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2: 652–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oncioiu Holban, Ionica, Anca-Gabriela Petrescu, Florentina-Raluca Bîlcan, Marius Petrescu, and Delia-Mioara Popescu. 2010. Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Financial Performance. Sustainability 12: 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkila, Tiina Johanna. 2009. Corporate argumentation for acceptability: Reflections of environmental values and stakeholder relations in corporate environmental statements. Journal of Business Ethics 87: 285–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jong-Hun, Changsu Kim, Young Kyun Chang, Dong-Hyun Lee, and Yun-Dal Sung. 2018. CEO hubris and firm performance: Exploring the moderating roles of CEO power and board vigilance. Journal of Business Ethics 147: 919–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, John A., and Richard B. Robinson. 2011. Strategic Management: Formulation, Implementation & Control, 12th ed. New York: Mcgraw Hill Higher Education, 992p. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, John Ben, and Neeraj Dwivedi. 2013. A third dimension to understanding voluntary disclosures. Journal of Business Strategy 34: 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, María Consuelo, and Isabel Gallego-Álvarez. 2019. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the discclosure of corporate social responsability issues. Corporate Social Responsability and Environmental Management 26: 612–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Yan, Amama Shaukat, and Rajesh Tharyan. 2016. Environmental and social disclosures: Link with corporate financial performance. The British Accounting Review 48: 102–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radomska, Joanna. 2014. Operational risk associated with the strategy implementation. Management 18: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raucci, Domenico Raucci, Lara Tarquinio, Daniela Rupo, and Salvatore Loprevite. 2020. Non-Financial Performance Indicators: The Power of Measures to Operationalize the Law. In Sustainability and Law. Edited by Volker Mauerhofer, Daniela Rupo and Lara Tarquinio. Cham: Springer, pp. 275–91. [Google Scholar]

- Renders, Annelies, Ann Gaeremynck, and Piet Sercu. 2010. Corporate-governance ratings and company performance: A cross-European study. Corporate Governance: An International Review 18: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. Smart PLS 3. Smart PLS GmbH Boenningstedt. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Rosenstein, Joseph, Albert V. Bruno, William D. Bygrave, and Natalie T. Taylor. 1993. The CEO, venture capitalists, and the board. Journal of Business Venturing 8: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, Sugata, Nemit Shroff, and Rodrigo S. Verdi. 2019. The Effects of Financial Reporting and Disclosure on Corporate Investment: A Review. Journal of Accounting and Economics 68: 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruigrok, Winfried, Simon I. Peck, and Hansueli Keller. 2006. Board characteristics and involvement in strategic decision-making: Evidence from Swiss companies. Journal of Management Studies 43: 1201–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, Harry J., and Anil K. Gupta. 1994. Impact of agency risks and task uncertainty on venture capitalist–CEO interactions. Academy of Management Journal 37: 1618–32. [Google Scholar]

- Scaltrito, Davide. 2015. Assessing Disclosure Quality: A Methodological Issue. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing 11: 466–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherer, Andreas Georg, and Christian Voegtlin. 2020. Corporate governance for responsible innovation: Approaches to corporate governance and their implications for sustainable development. Academy of Management Perspectives 34: 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, Andrew K., and Edward C. Tomlinson. 2016. Organizational Transparency a New Perspective on Managing Trust in Organization-Stakeholder Relationships. Journal of Management 42: 1784–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, Renard Y. J. 2015. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Journal of Environmental Management 164: 180–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Justine, and John R. Taylor. 2013. Corporate Governance, Ethics and CSR, 1st ed. London: Kogan Page, 297p, ISBN 978-0749463854. [Google Scholar]

- Stanwick, Sarah D., and Peter A. Stanwick. 2000. The relationship between environmental disclosures and financial performance: An empirical study of US firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 7: 155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, Rao A. V., and Daniel Zeghal. 1997. Human resource Information Disclosure in Annual reports: An international Comparison. Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting 2: 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theyel, Gregory, and Kay Hofmann. 2012. Stakeholder relations and sustainability practices of U.S. small and medium-sized manufacturers. Management Research Review 35: 1110–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron Tudor, Adriana. 2006. Disclosure and Transparency of Romanian Listed Companies. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=920580 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Tracy, Artiach, Darren Lee, David Nelson, and Julie Walker. 2010. The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Accounting and Finance 50: 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- UN/United Nations. 2016. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Official Journal of the European Union L 282/4. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22016A1019(01)&from=EN (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Valaskova, Katarina, Tomas Kliestik, and Dominika Gajdosikova. 2021. Distinctive determinants of financial indebtedness: Evidence from Slovak and Czech enterprises. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 16: 639–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horne, James C., and John M. Wachowicz Jr. 2005. Fundamentals of Financial Management, 12th ed. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

| No. Line | The Symbol of Main Categories | List of Independent Variables |

|---|---|---|

| I. | CG | Corporate governance |

| 1.1. | CG1 | Corporate governance structure |

| 1.2. | CG2 | Managerial strategies |

| 1.3. | CG3 | Advising committees of the Board of Directors |

| II. | HR | Human Resources |

| 2.1. | HR1 | Number of employees |

| 2.2. | HR2 | Company’s personnel reward policy |

| 2.3. | HR3 | Innovations and initiatives |

| 2.4. | HR4 | Professional experience of top managers |

| III. | SD | Sustainable development |

| 3.1. | SD1 | Business overview |

| 3.2. | SD2 | Key events |

| 3.3. | SD3 | Research and Development |

| IV. | PRFR | Performance, risks and financial reports |

| 4.1. | PRFR1 | Financial performance |

| 4.2. | PRFR2 | Risk management |

| 4.3. | PRFR3 | Financial reports |

| No. Line | Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CG | 0.620 | 0.702 | 0.794 | 0.568 |

| 2. | HR | 0.635 | 0.685 | 0.802 | 0.578 |

| 3. | PRFR | 0.604 | 0.670 | 0.770 | 0.526 |

| 4. | SD | 0.618 | 0.540 | 0.758 | 0.517 |

| No. Line | Relationship | Path Coefficient | T Statistics | p Values | Validation of the Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CG → Transparency | 0.394 | 4.521 | 0.000 | Yes |

| 2. | HR → Transparency | 0.300 | 2.800 | 0.005 | Yes |

| 3. | PFS → Transparency | 0.214 | 2.414 | 0.016 | Yes |

| 4. | SD → Transparency | 0.158 | 1.691 | 0.091 | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bostan, I.; Bîrcă, A.; Bîrcă, A.; Sandu, C.B. Global Top E-Commerce Companies: Transparency Analysis Based on Annual Reports. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15070313

Bostan I, Bîrcă A, Bîrcă A, Sandu CB. Global Top E-Commerce Companies: Transparency Analysis Based on Annual Reports. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(7):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15070313

Chicago/Turabian StyleBostan, Ionel, Alic Bîrcă, Aliona Bîrcă, and Christiana Brigitte Sandu. 2022. "Global Top E-Commerce Companies: Transparency Analysis Based on Annual Reports" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 7: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15070313

APA StyleBostan, I., Bîrcă, A., Bîrcă, A., & Sandu, C. B. (2022). Global Top E-Commerce Companies: Transparency Analysis Based on Annual Reports. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(7), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15070313