Millennial Generation’s Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing, Perceived Financial Risk, Knowledge of Riba, and Marketing Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Development of the Hypothesis

2.1. Theories

2.2. Attitude

2.3. Subjective Norm

2.4. Profit and Loss Sharing

2.5. Percieved Financial Risk

2.6. Knowledge of Riba

2.7. Relationship Marketing

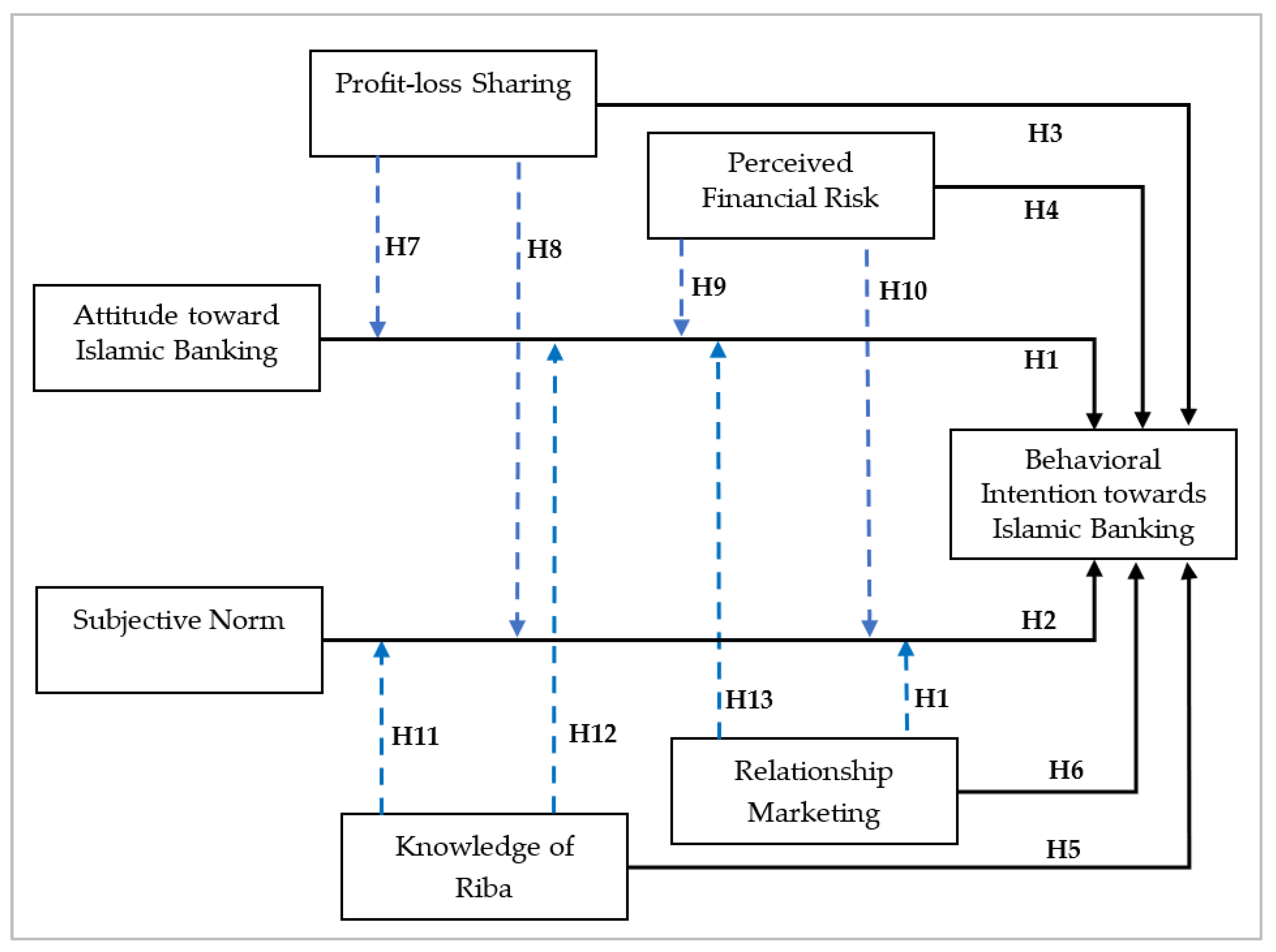

2.8. Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing

2.9. Moderating Role of Perceived Financial Risk

2.10. Moderating Role of Knowledge of Riba

2.11. Moderating Role of Relationship Marketing

2.12. Conceptual Research Model

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Empirical Estimation

3.1.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.1.2. Measurement Reflective Model

3.1.3. Structural Estimation Model

4. Empirical Findings

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ab. Rahim, Fithriah, and Hanudin Amin. 2011. Determinants of Islamic Insurance Acceptance: An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Business and Society 12: 37. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, Rose, and Ahmad Lutfi Abdul Razak. 2015. Exploratory Research into Islamic Financial Literacy in Brunei Darussalam. In Researchgate.Net. Bandar Seri Begawan: Universitas Islam Sultan Sharif Ali. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Rahman, Aisyah, Radziah Abdul Latif, Ruhaini Muda, and Muhammad Azmi Abdullah. 2014. Failure and Potential of Profit-Loss Sharing Contracts: A Perspective of New Institutional, Economic (NIE) Theory. Pacific Basin Finance Journal 28: 136–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, Ali, and Shang Jie. 2022. Understanding Farmers’ Decision-Making to Use Islamic Finance through the Lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Islamic Marketing, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Abu Umar Faruq, and M. Kabir Hassan. 2007. Riba and Islamic Banking. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance 3: 961–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Gatot Nazir, Umi Widyastuti, Santi Susanti, and Hasan Mukhibad. 2020. Determinants of the Islamic Financial Literacy. Accounting 6: 961–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Selim, Muhammad Mohiuddin, Mahfuzur Rahman, Kazi Md Tarique, and Md Azim. 2021. The Impact of Islamic Shariah Compliance on Customer Satisfaction in Islamic Banking Services: Mediating Role of Service Quality. Journal of Islamic Marketing 13: 1829–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, Hendy Mustiko, Izra Berakon, and Alex Fahrur Riza. 2020. The Effects of Subjective Norm and Knowledge about Riba on Intention to Use E-Money in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 12: 1180–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, Hendy Mustiko, Izra Berakon, and Muamar Nur Kholid. 2019. The Moderating Role of Knowledge about Riba on Intention to Use E-Money: Findings from Indonesia. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE 6th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications, ICIEA 2019, Tokyo, Japan, April 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 2012. Martin Fishbein’s Legacy: The Reasoned Action Approach. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 640: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 2020. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2: 314–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1977. Attitude-Behavior Relations: A Theoretical Analysis and Review of Empirical Research. Psychological Bulletin 84: 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-alak, Basheer A. 2014. Impact of Marketing Activities on Relationship Quality in the Malaysian Banking Sector. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21: 347–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaity, Mohamed, and Mahfuzur Rahman. 2019. The Intention to Use Islamic Banking: An Exploratory Study to Measure Islamic Financial Literacy. International Journal of Emerging Markets 14: 988–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albashir, Walid, Zainuddin Yuserrie, and Shrikant Panigrahi. 2017. Conceptual Framework on Usage of Islamic Banking amongst Banking Customers in Libya. International Journal of Innovation and Business Strategy (IJIBS) 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Afzaal, Guo Xiaoling, Mehkar Sherwani, and Adnan Ali. 2017. Factors Affecting Halal Meat Purchase Intention: Evidence from International Muslim Students in China. British Food Journal 119: 527–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaiee, Laith, and Nahla Al-Nazer. 2010. Investigate the Impact of Relationship Marketing Orientation on Customer Loyalty: The Customer’s Perspective. International Journal of Marketing Studies 2: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hanudin, Abdul Rahim Abdul-Rahman, and Dzuljastri Abdul-Razak. 2013. An Integrative Approach for Understanding Islamic Home Financing Adoption in Malaysia. International Journal of Bank Marketing 31: 544–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hanudin, and M. Kabir Hassan. 2022. Millennials’ Acceptability of Tawarruq-Based Ar-Rahnu in Malaysia. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Muslim, Sajad Rezaei, and Maryam Abolghasemi. 2014. User Satisfaction with Mobile Websites: The Impact of Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Trust. Nankai Business Review International 5: 258–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, Z. Hafsa Orhan. 2013. Survey on Customer Related Studies in Islamic Banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing 4: 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, Okeke, and Nwachukwu Kene Kingsley. 2020. Assessment of the Banking Behaviour of Generation Y University Students and the Future of Retail Banking in North Central Nigeria. Research Journal of Social Sciences 2: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, Hayat M., and Khuram Shahzad Bukhari. 2011. Customer’s Criteria for Selecting an Islamic Bank: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2: 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, Amer, Abdul Jamal, Wijaya Kamal, Ramlan Mohdrahimie, Abdul Karim Roslemohidin, and Zaiton Osman. 2015. The Effects of Social Influence and Financial Literacy on Savings Behavior: A Study on Students of Higher Learning Institutions in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. International Journal of Business and Social Science 6: 110–19. Available online: file:/https://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_6_No_11_1_November_2015/12.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Basha, Mohamed Bilal, Abid Mahmood Muhammad, and Gail Alhafidh. 2021. Bank Selection for SMEs: An Emirati Student Perspective. Transnational Marketing Journal 3: 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Irfan, and Chendragiri Madhavaiah. 2015. Consumer Attitude and Behavioural Intention towards Internet Banking Adoption in India. Journal of Indian Business Research 7: 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechler, Steven M. 1995. New Social Movement Theories. Sociological Quarterly 36: 441–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, David, Audrey Gilmore, and Susan Walsh. 2004. Balancing Transaction and Relationship Marketing in Retail Banking. Journal of Marketing Management 20: 431–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, Elfreda A. 1986. Diffusion Theory: A Review and Test of a Conceptual Model in Information Diffusion. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 37: 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T. C. Edwin, David Y. C. Lam, and Andy C. L. Yeung. 2006. Adoption of Internet Banking: An Empirical Study in Hong Kong. Decision Support Systems 42: 1558–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Jyh Shen, and Chung Chi Shen. 2012. The Antecedents of Online Financial Service Adoption: The Impact of Physical Banking Services on Internet Banking Acceptance. Behaviour and Information Technology 31: 859–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Beng Soon, and Ming Hua Liu. 2009. Islamic Banking: Interest-Free or Interest-Based? Pacific Basin Finance Journal 17: 125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, Robert A., and Denise M. Rousseau. 1988. Behavioral Norms and Expectations: A Quantitative Approach to the Assessment of Organizational Culture. Group & Organization Management 13: 245–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, Russell, and Marie S. Mitchell. 2005. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management 31: 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, Humayon A., and John R. Presley. 2000. Lack of Profit Loss Sharing in Islamic Banking: Management and Control Imbalances. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services 2: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Fred D., Richard P. Bagozzi, and Paul R. Warshaw. 1989. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science 35: 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Madariaga, J. Garcia, and Carmen Valor. 2007. Stakeholders Management Systems: Empirical Insights from Relationship Marketing and Market Orientation Perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics 71: 425–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, Hein, Margo Dijkstra, and Piet Kuhlman. 1988. Self-Efficacy: The Third Factor besides Attitude and Subjective Norm as a Predictor of Behavioural Intentions. Health Education Research 3: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusuki, Asyraf Wajdi, and Nurdianawati Irwani Abdullah. 2007. Why Do Malaysian Customers Patronise Islamic Banks? International Journal of Bank Marketing Managerial Finance Iss International Journal of Bank Marketing 25: 142–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, Ihsan, Miftahuddin Murad, Ahmad Rafiki, and Mitra Musika Lubis. 2020a. The Application of the Theory of Reasoned Action on Services of Islamic Rural Banks in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 12: 951–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, Mohamad Irhas, Dyah Sugandini, Agus Sukarno, Muhamad Kundarto, and Rahajeng Arundati. 2020b. The Theory of Planned Behavior and Pro-Environmental Behavior among Students. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 11: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseidi, Reham I. 2018. Determinants of Halal Purchasing Intentions: Evidences from UK. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 167–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, Cengiz, and Radi El-Bdour. 1989. Attitudes, Behaviour and Patronage Factors of Bank Customers towards Islamic Banks. International Journal of Bank Marketing 7: 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, Precious Chikezie, and Anayo D. Nkamnebe. 2022. Determinants of Islamic Banking Adoption among Non-Muslim Customers in a Muslim Zone. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 13: 666–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, Mauricio S., and Paul A. Pavlou. 2003. Predicting E-Services Adoption: A Perceived Risk Facets Perspective. International Journal of Human Computer Studies 59: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1975. Chapter 1. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Jen Ruei, Cheng Kiang Farn, and Wen Pin Chao. 2006. Acceptance of Electronic Tax Filing: A Study of Taxpayer Intentions. Information and Management 43: 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, Philip, and J. Barton Cunningham. 1997. Islamic Banking: A Study in Singapore. International Journal of Bank Marketing 15: 204–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, Christian. 2004. The Relationship Marketing Process: Communication, Interaction, Dialogue, Value. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 19: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, Martin S. 2019. Habit and Physical Activity: Theoretical Advances, Practical Implications, and Agenda for Future Research. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 42: 118–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Jr., Lucy M. Matthews, Ryan L. Matthews, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1: 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019a. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2019b. Multivariate Data Analysis. New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, Ayesha, and Omar Masood. 2011. Selection Criteria for Islamic Home Financing: A Case Study of Pakistan. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 3: 117–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Ahasanul, Abdullah Sarwar, Farzana Yasmin, Arun Kumar Tarofder, and Mirza Ahsanul Hossain. 2015. Non-Muslim Consumers’ Perception toward Purchasing Halal Food Products in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 6: 133–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, Sudin, Norafifah Ahmad, and Sandra L. Planisek. 1994. Bank Patronage Factors of Muslim and Non-Muslim Customers. International Journal of Bank Marketing 12: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, Joo Gim, and Ronald E. Goldsmith. 1999. External Information Search for Banking Services. International Journal of Bank Marketing 17: 305–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, Joseph. 2015. Culture and Social Behavior. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 3: 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, Nancy B. 2007. Transporting Pedagogy: Implementing the Project Approach in Two First-Grade Classrooms. Journal of Advanced Academics 18: 530–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidajat, Taofik, and Muliawan Hamdani. 2017. Measuring Islamic Financial Literacy. Advanced Science Letters 23: 7173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Mohammad Enamul, M. Kabir Hassan, Nik Mohd Hazrul Nik Hashim, and Tarek Zaher. 2019. Factors Affecting Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Effects of Customer Marketing Practices and Financial Considerations. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 24: 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Mohammad Enamul, Nik Mohd Hazrul Nik Hashim, and Mohammad Hafizi Bin Azmi. 2018a. Moderating Effects of Marketing Communication and Financial Consideration on Customer Attitude and Intention to Purchase Islamic Banking Products: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Mohammad Enamul, Nik Mohd Hazrul Nik Hashim, and Mohammed Abdur Razzaque. 2018b. Effects of Communication and Financial Concerns on Banking Attitude-Behaviour Relations. Service Industries Journal 38: 1017–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBS. 2021. Development of Islamic Economics Based on Publicity. Indonesia Banking School. Available online: http://ibs.ac.id/en/development-of-islamic-economics-based-on-publicity/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Jalil, Md Abdul, and Muhammad Khalilur Rahman. 2014. The Impact of Islamic Branding on Consumer Preference towards Islamic Banking Services: An Empirical Investigation in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Banking and Finance 2: 209–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jham, Vimi, and Kaleem Mohd Khan. 2008. Determinants of Performance in Retail Banking: Perspectives of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Marketing. Singapore Management Review 30: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Josiassen, Alexander, Bryan A. Lukas, and Gregory J. Whitwel. 2017. Country-of-Origin Contingencies: Competing Perspectives on Product Familiarity and Product Involvement. The Eletronic Library 34: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Junaidi, Junaidi, Suhardi M. Anwar, Roslina Alam, Niniek F. Lantara, and Ready Wicaksono. 2022. Determinants to Adopt Conventional and Islamic Banking: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, Hajime, and Kenichi Kashiwagi. 2019. Factors Affecting Customers’ Continued Intentions to Use Islamic Banks. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 24: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamla, Rania, and Rana Alsoufi. 2015. Critical Muslim Intellectuals’ Discourse and the Issue of ‘Interest’ (Ribā): Implications for Islamic Accounting and Banking. Accounting Forum 39: 140–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalek, Aiedah Abdul, and Sharifah Hayaati Syed Ismail. 2015. Why Are We Eating Halal—Using the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Halal Food Consumption among Generation Y in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 5: 608–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Eojina, Sunny Ham, Il Sun Yang, and Jeong Gil Choi. 2013. The Roles of Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control in the Formation of Consumers’ Behavioral Intentions to Read Menu Labels in the Restaurant Industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 35: 203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lada, Suddin, Geoffrey Harvey Tanakinjal, and Hanudin Amin. 2009. Predicting Intention to Choose Halal Products Using Theory of Reasoned Action. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 2: 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, Michel, Marcelo Vinhal Nepomuceno, and Marie Odile Richard. 2010. How Do Involvement and Product Knowledge Affect the Relationship between Intangibility and Perceived Risk for Brands and Product Categories? Journal of Consumer Marketing 27: 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Kyun, and Wei Na Lee. 2009. Country-of-Origin Effects on Consumer Product Evaluation and Purchase Intention: The Role of Objective versus Subjective Knowledge. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 21: 137–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverin, Andreas, and Veronica Liljander. 2006. Does Relationship Marketing Improve Customer Relationship Satisfaction and Loyalty? International Journal of Bank Marketing 24: 232–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Barbara R. 1982. Student Accounts—A Profitable Segment? European Journal of Marketing 16: 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, Sandra Maria Correia, Hans Rüdiger Kaufmann, and Samuel Rabino. 2014. Intentions to Use and Recommend to Others: An Empirical Study of Online Banking Practices in Portugal and Austria. Online Information Review 38: 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujja, Sulaiman, Mustafa Omar Mohammad, and Rusni Hassan. 2016. Modelling Public Behavioral Intention to Adopt Islamic Banking in Uganda: The Theory of Reasoned Action. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 9: 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdzan, Nurul Shahnaz, Rozaimah Zainudin, and Sook Fong Au. 2017. The Adoption of Islamic Banking Services in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaquias, Rodrigo F., and Yujong Hwang. 2016. An Empirical Study on Trust in Mobile Banking: A Developing Country Perspective. Computers in Human Behavior 54: 453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrik, Carter A., and Yeqing Bao. 2005. Exploring the Concept and Measurement of General Risk Aversion. Advances in Consumer Research 32: 531–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marimuthu, Maran, Chan Wai Jing, Lim Phei Gie, Low Pey Mun, and Tan Yew Ping. 2010. Islamic Banking: Selection Criteria and Implications. Global Journal of Human Social Science 10. [Google Scholar]

- Mbawuni, Joseph, and Simon Gyasi Nimako. 2018. Muslim and Non-Muslim Consumers’ Perception towards Introduction of Islamic Banking in Ghana. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 9: 353–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrindle, Mark. 2014. The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations. Randwick: UNSW Press. ISBN1 1742240194. ISBN2 9781742240190. [Google Scholar]

- Metawa, Saad A., and Mohammed Almossawi. 1998. Banking Behavior of Islamic Bank Customers: Perspectives and Implications. International Journal of Bank Marketing 16: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindra, Rachel, Juma Bananuka, Twaha Kaawaase, Rehma Namaganda, and Juma Teko. 2022. Attitude and Islamic Banking Adoption: Moderating Effects of Pricing of Conventional Bank Products and Social Influence. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 13: 534–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nor, Amirudin, and Shafinar Ismail. 2020. Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS) and Non-PLS Financing in Malaysia: Which One Should Be the One? KnE Social Sciences 4: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhlis, Safiek, Nik Hazimah, Nik Mat, and Hayatul Safrah Salleh. 2008. Commercial Bank Selection: The Case of Undergraduate Students in Malaysia. International Review of Business Research Papers 4: 258–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mulia, Dipa, Hardius Usman, and Novia Budi Parwanto. 2020. The Role of Customer Intimacy in Increasing Islamic Bank Customer Loyalty in Using E-Banking and m-Banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing 12: 1097–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, Hussam, Zdenka Musova, Viacheslav Natorin, George Lazaroiu, and Martin Boďa. 2021. Comparison of Factors Influencing Liquidity of European Islamic and Conventional Banks. Oeconomia Copernicana 12: 375–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyahidah, Siti, Ermawati Ermawati, and Nurdin Nurdin. 2021. The Effect of Riba Avoidance and Product Knowledge on the Decision to Become a Customer of Islamic Banks. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum C., and Ira H. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Keunyoung, and Liza Abraham. 2016. Effect of Knowledge on Decision Making in the Context of Organic Cotton Clothing. International Journal of Consumer Studies 40: 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OJK. 2021. Sharia Banking Statistics. Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. Indonesia. Available online: https://www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/syariah/data-dan-statistik/statistik-perbankan-syariah/default.aspx (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Othman, A., and L. Owen. 2001. Adopting and Measuring Customers Service Quality (SQ) in Islamic Banks: A Case Study in Kuwait Finance House. International Journal of Islamic Financial Service 3: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Penz, Elfriede, and Margaret K. Hogg. 2011. The Role of Mixed Emotions in Consumer Behaviour: Investigating Ambivalence in Consumers’ Experiences of Approach-Avoidance Conflicts in Online and Offline Settings. European Journal of Marketing 45: 104–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, Ian, and Charise Woo. 2008. Understanding Compulsive Buying Tendencies among Young Australians: The Roles of Money Attitude and Credit Card Usage. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 26: 441–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollay, Richard W., and Banwari Mittal. 1993. Here’s the Beef: Factors, Determinants, and Segments in Consumer Criticism of Advertising. Journal of Marketing 57: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourkiani, Masoud, Mehrdad Goudarzvand Chegini, Samin Yousefi, and Shiva Madahian. 2014. Service Quality Effect on Satisfaction and Word of Mouth in Insurance Industry. Management Science Letters 4: 1773–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, G., Keshavamurthy Ramamurthy, and Sree Nilakanta. 1994. Implementation of Electronic Data Interchange: An Innovation Diffusion Perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems 11: 157–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T., Kamel Rouibah, M. Gopi, and Gary John Rangel. 2009. A Decomposed Theory of Reasoned Action to Explain Intention to Use Internet Stock Trading among Malaysian Investors. Computers in Human Behavior 25: 1222–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, Dzuljastri Abdul, and Fauziah Md Taib. 2011. Consumers’ Perception on Islamic Home Financing: Empirical Evidences on Bai Bithaman Ajil (BBA) and Diminishing Partnership (DP) Modes of Financing in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselius, Ted. 1971. Consumer Rankings of Risk Reduction Methods. Journal of Marketing 35: 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, Methaq Ahmed, and Fahad Ali Algammash. 2016. The Effect of Attitude toward Advertisement on Attitude toward Brand and Purchase Intention. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management United Kingdom 4: 509–20. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, Sarminah, Muhammad Kashif, Shanika Wijeneyake, and Michela Mingione. 2021. Islamic Religiosity and Ethical Intentions of Islamic Bank Managers: Rethinking Theory of Planned Behaviour. Journal of Islamic Marketing 13: 2421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, Marko, Joseph F. Hair, Jun Hwa Cheah, Jan Michael Becker, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher-Order Constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal 27: 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsios, Nikolaos, and Spyros Hadjidakis. 2018. Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) in Saving Behaviour of Pomak Households. International Journal of Financial Research 9: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sayani, Hameedah, and Hela Miniaoui. 2013. Determinants of Bank Selection in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Bank Marketing 31: 206–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, Jeroen, and Martin Wetzels. 2007. A Meta-Analysis of the Technology Acceptance Model: Investigating Subjective Norm and Moderation Effects. Information and Management 44: 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shome, Anamitra, Fauzia Jabeen, and Rajesh Rajaguru. 2018. What Drives Consumer Choice of Islamic Banking Services in the United Arab Emirates? International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 11: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Muhammad Zahid. 2022. Modern Money and Islamic Banking in the Light of Islamic Law of Riba. International Journal of Finance and Economics 27: 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, Sreeram, Mala Srivastava, and Anupam Rastogi. 2017. Attitudinal Factors, Financial Literacy, and Stock Market Participation. International Journal of Bank Marketing 35: 818–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, Nizar, and Marzouki Rani. 2015. Consumer Attitudes and Purchase Intentions toward Islamic Banks: The Influence of Religiosity. International Journal of Bank Marketing 33: 143–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Kavita, and Narendra K. Sharma. 2011. Exploring the Multidimensional Role of Involvement and Perceived Risk in Brand Extension. International Journal of Commerce and Management 21: 410–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Kavita, and Narendra K. Sharma. 2013. Consumer Attitude towards Brand Extension: A Comparative Study of Fast Moving Consumer Goods, Durable Goods and Services. Journal of Indian Business Research 5: 177–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Mrinalini, Gagan Deep Sharma, and Achal Kumar Srivastava. 2019. Human Brain and Financial Behavior: A Neurofinance Perspective. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 35: 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, Dwi, Christopher Gan, Tomy Andrianto, Tuan Ahmad Tuan Ismail, and Nono Wibisono. 2021. Holistic Tourist Experience in Halal Tourism Evidence from Indonesian Domestic Tourists. Tourism Management Perspectives 40: 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, Perengki, Mohammad Enamul Hoque, Nik Mohd Hazrul Nik Hashim, Najeeb Ullah Shah, and Mohammad Nur A. Alam. 2022. Moderating Effects of Perceived Risk on the Determinants–Outcome Nexus of e-Money Behaviour. International Journal of Emerging Markets 17: 530–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, Rakhi, and Mala Srivastava. 2014. Adoption Readiness, Personal Innovativeness, Perceived Risk and Usage Intention across Customer Groups for Mobile Payment Services in India. Internet Research 24: 369–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambiah, Seethaletchumy, Hishamuddin Ismail, and Chinnasamy A. Malarvizhi. 2011. Islamic Retail Banking Adoption: A Conceptual Framework. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 5: 649–57. [Google Scholar]

- Thambiah, Seethaletchumy, Uchenna Cyril Eze, Khong Sin Tan, Robert Jeyakumar Nathan, and Kim Piew Lai. 2010. Conceptual Framework for the Adoption of Islamic Retail Banking Services in Malaysia. Journal of Electronic Banking Systems 2010: 750059. [Google Scholar]

- Thwaites, Des, and Lizanne Vere. 1995. Bank Selection Criteria—A Student Perspective. Journal of Marketing Management 11: 133–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingchi Liu, Matthew, James L. Brock, Gui Cheng Shi, Rongwei Chu, and Ting Hsiang Tseng. 2013. Perceived Benefits, Perceived Risk, and Trust: Influences on Consumers’ Group Buying Behaviour. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 25: 225–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootelian, Dennis H., and Ralph M. Gaedeke. 1996. Targeting the College Market for Banking Services. Journal of Professional Services Marketing 14: 161–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Mark, and Christine Jubb. 2018. Bank and Product Selection—An Australian Student Perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 126–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Mark, Christine Jubb, and Chee Jin Yap. 2020. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and Student Banking in Australia. International Journal of Bank Marketing 38: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Shakir, and Kun Ho Lee. 2012. Do Customers Patronize Islamic Banks for Sharia Compliance. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 17: 206–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Shakir, and Kun Ho Lee. 2016. Do Customers Patronize Islamic Banks for Shari’a Compliance? In Islamic Finance: Principles, Performance and Prospects. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Shakir, Ian A. Harwood, and Dima Jamali. 2018. ‘Fatwa Repositioning’: The Hidden Struggle for Shari’a Compliance Within Islamic Financial Institutions. Journal of Business Ethics 149: 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, Hardius, Nucke Widowati Kusumo Projo, Chairy Chairy, and Marissa Grace Haque. 2022. The Exploration Role of Sharia Compliance in Technology Acceptance Model for E-Banking (Case: Islamic Bank in Indonesia). Journal of Islamic Marketing 13: 1089–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Susan, Audrey Gilmore, and David Carson. 2004. Managing and Implementing Simultaneous Transaction and Relationship Marketing. International Journal of Bank Marketing 22: 468–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watjatrakul, Boonlert. 2013. Intention to Use a Free Voluntary Service: The Effects of Social Influence, Knowledge and Perceptions. Journal of Systems and Information Technology 15: 202–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, Umi, Ati Sumiati, Herlitah, and Inaya Sari Melati. 2020. Financial Education, Financial Literacy, and Financial Behaviour: What Does Really Matter? Management Science Letters 10: 2715–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Kaylene C., and Robert A. Page. 2015. Marketing to the Generations. Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business 3: 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yasri, Yasri, Perengki Susanto, Mohammad Enamul Hoque, and Mia Ayu Gusti. 2020. Price Perception and Price Appearance on Repurchase Intention of Gen Y: Do Brand Experience and Brand Preference Mediate? Heliyon 6: e05532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulaihati, Sri, Santi Susanti, and Umi Widyastuti. 2020. Teachers’ Financial Literacy: Does It Impact on Financial Behaviour? Management Science Letters 10: 653–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 436 | 79.85 |

| Men | 110 | 20.15 | |

| Age | <20 years | 216 | 39.56 |

| ≥20 years | 330 | 60.44 | |

| Bath | 2016 | 8 | 1.47 |

| 2017 | 43 | 7.88 | |

| 2018 | 136 | 24.91 | |

| 2019 | 359 | 65.75 | |

| Allowance/month (IDR) | <1 million | 518 | 94.87 |

| 1–4 million | 26 | 4.76 | |

| >4 million | 2 | 0.37 | |

| Total | 546 | 100.00 |

| Constructs/Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward Islamic Banking | 0.814 | 0.878 | |

| Choosing Islamic banking service is a good idea. | 0.830 | ||

| When it comes to banking, I prefer Islamic banking service. | 0.867 | ||

| The majority of important people in my life have chosen Islamic banking. | 0.792 | ||

| A member of my family prefers Islamic banking services. | 0.713 | ||

| Subjective Norm | 0.828 | 0.885 | |

| I know a lot of people who use Islamic banking services. | 0.787 | ||

| Islamic banking service is used by important people in my life. | 0.820 | ||

| The majority of people I know would support my decision to use Islamic banking service. | 0.813 | ||

| The majority of people I know believe I should use Islamic banking. | 0.827 | ||

| Profit-loss Sharing | 0.838 | 0.925 | |

| If the business managed by Mudharabah makes a profit, the partner and capital owner will share the profit according to the proportions agreed upon before the contract was signed. | 0.928 | ||

| The profit earned in a Musyarakah contract must be shared proportionally. | 0.928 | ||

| Perceived Financial Risk | 0.753 | 0.857 | |

| It is critical to avoid financial losses. | 0.751 | ||

| Satisfactory banking services are important to me | 0.865 | ||

| It is critical that using a bank’s service does not cause me any inconvenience. | 0.830 | ||

| Knowledge of Riba | 0.712 | 0.838 | |

| The process of exchanging similar goods with a different dose or level is Riba | 0.770 | ||

| The additional money required in a debt transaction is Riba. | 0.832 | ||

| In an installment transaction, the penalty is referred to as Riba. | 0.786 | ||

| Relationship Marketing | 0.936 | 0.946 | |

| Customer contact at the bank is governed by a set of guidelines. | 0.758 | ||

| Customers are treated with respect by employees. | 0.815 | ||

| The bank has a high level of integrity. | 0.853 | ||

| The bank has a good reputation. | 0.809 | ||

| bank communicate frequently | 0.828 | ||

| The bank’s employees communicate in a friendly manner. | 0.857 | ||

| The bank makes every effort to establish long-term relationships. | 0.802 | ||

| I am satisfied with all of the services provided. | 0.766 | ||

| Continue to be a client in order to benefit from the relationship. | 0.826 | ||

| Behavioral Intention towards Islamic Banking | 0.867 | 0.903 | |

| I intend to continue using Islamic banking services. | 0.822 | ||

| I will recommend the online service to my friends and family. | 0.771 | ||

| If someone asks for my opinion, I will recommend Islamic banking services. | 0.810 | ||

| I will tell others about the Islamic banking service in a positive light. | 0.834 | ||

| I will recommend the online service to my friends and family.I intend to use the online Islamic banking service on a regular basis in the future. | 0.796 |

| Constructs | AVE | Correlation of Constructs Based on Fornell-Lakarckers Criterion | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.644 | 0.802 | ||||||

| Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.651 | 0.55 | 0.807 | |||||

| Knowledge of Riba (KNO) | 0.634 | 0.386 | 0.438 | 0.796 | ||||

| Perceived Financial Risk (RIS) | 0.667 | −0.47 | −0.51 | −0.48 | 0.817 | |||

| Profit-loss Sharing (SHA) | 0.861 | 0.398 | 0.604 | 0.415 | −0.42 | 0.928 | ||

| Relationship Marketing (REL) | 0.662 | 0.489 | 0.693 | 0.42 | −0.59 | 0.55 | 0.813 | |

| Subjective Norm (SUB) | 0.659 | 0.668 | 0.549 | 0.319 | −0.39 | 0.348 | 0.524 | 0.812 |

| Constructs | AVE | Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.644 | 1 | ||||||

| Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.651 | 0.646 | 1 | |||||

| Knowledge of Riba (KNO) | 0.634 | 0.499 | 0.549 | 1 | ||||

| Perceived Financial Risk (RIS) | 0.667 | 0.582 | 0.619 | 0.661 | 1 | |||

| Profit-loss Sharing (SHA) | 0.861 | 0.48 | 0.699 | 0.533 | 0.523 | 1 | ||

| Relationship Marketing (REL) | 0.662 | 0.559 | 0.759 | 0.509 | 0.703 | 0.622 | 1 | |

| Subjective Norm (SUB) | 0.659 | 0.817 | 0.643 | 0.411 | 0.483 | 0.414 | 0.591 | 1 |

| Relationships | Path | STDEV | t-Value | p-Value | Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | |||||

| Attitude (ATT) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.144 | 0.044 | 3.240 | 0.001 | H1 Supported |

| Subjective Norm (SUB) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.130 | 0.041 | 3.181 | 0.001 | H2 Supported |

| Profit-loss Sharing (SHA) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.258 | 0.038 | 6.770 | 0.000 | H3 Supported |

| Perceived Financial Risk (RIS) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | −0.062 | 0.044 | 1.477 | 0.140 | H4 Supported |

| Knowledge of Riba (KNO) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.065 | 0.036 | 1.798 | 0.072 | H5 Supported |

| Relationship Marketing (REL) → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.380 | 0.045 | 8.470 | 0.000 | H6 Supported |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| ATT*SHA → Behavioral Intention (INT) | −0.129 | 0.050 | 2.588 | 0.010 | H7 Not Supported |

| SUB*SHA → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.104 | 0.052 | 2.033 | 0.042 | H8 Supported |

| ATT*RIS → Behavioral Intention (INT) | −0.022 | 0.046 | 0.451 | 0.652 | H9 Not supported |

| SUB*RIS → Behavioral Intention (INT) | −0.017 | 0.054 | 0.382 | 0.703 | H10 Not supported |

| ATT*KNO → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.133 | 0.044 | 3.068 | 0.002 | H11 Supported |

| SUB*KNO → Behavioral Intention (INT) | −0.157 | 0.045 | 3.606 | 0.000 | H12 Supported |

| ATT*REL → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.055 | 0.056 | 1.019 | 0.308 | H13 Not supported |

| SUB*REL → Behavioral Intention (INT) | 0.022 | 0.058 | 0.349 | 0.727 | H14 Not supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asyari; Hoque, M.E.; Hassan, M.K.; Susanto, P.; Jannat, T.; Mamun, A.A. Millennial Generation’s Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing, Perceived Financial Risk, Knowledge of Riba, and Marketing Relationship. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15120590

Asyari, Hoque ME, Hassan MK, Susanto P, Jannat T, Mamun AA. Millennial Generation’s Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing, Perceived Financial Risk, Knowledge of Riba, and Marketing Relationship. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(12):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15120590

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsyari, Mohammad Enamul Hoque, M. Kabir Hassan, Perengki Susanto, Taslima Jannat, and Abdullah Al Mamun. 2022. "Millennial Generation’s Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing, Perceived Financial Risk, Knowledge of Riba, and Marketing Relationship" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 12: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15120590

APA StyleAsyari, Hoque, M. E., Hassan, M. K., Susanto, P., Jannat, T., & Mamun, A. A. (2022). Millennial Generation’s Islamic Banking Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Role of Profit-Loss Sharing, Perceived Financial Risk, Knowledge of Riba, and Marketing Relationship. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(12), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15120590