Determinants of EMNEs’ Entry Mode Decision with Environmental Volatility Issues: A Review and Research Agenda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

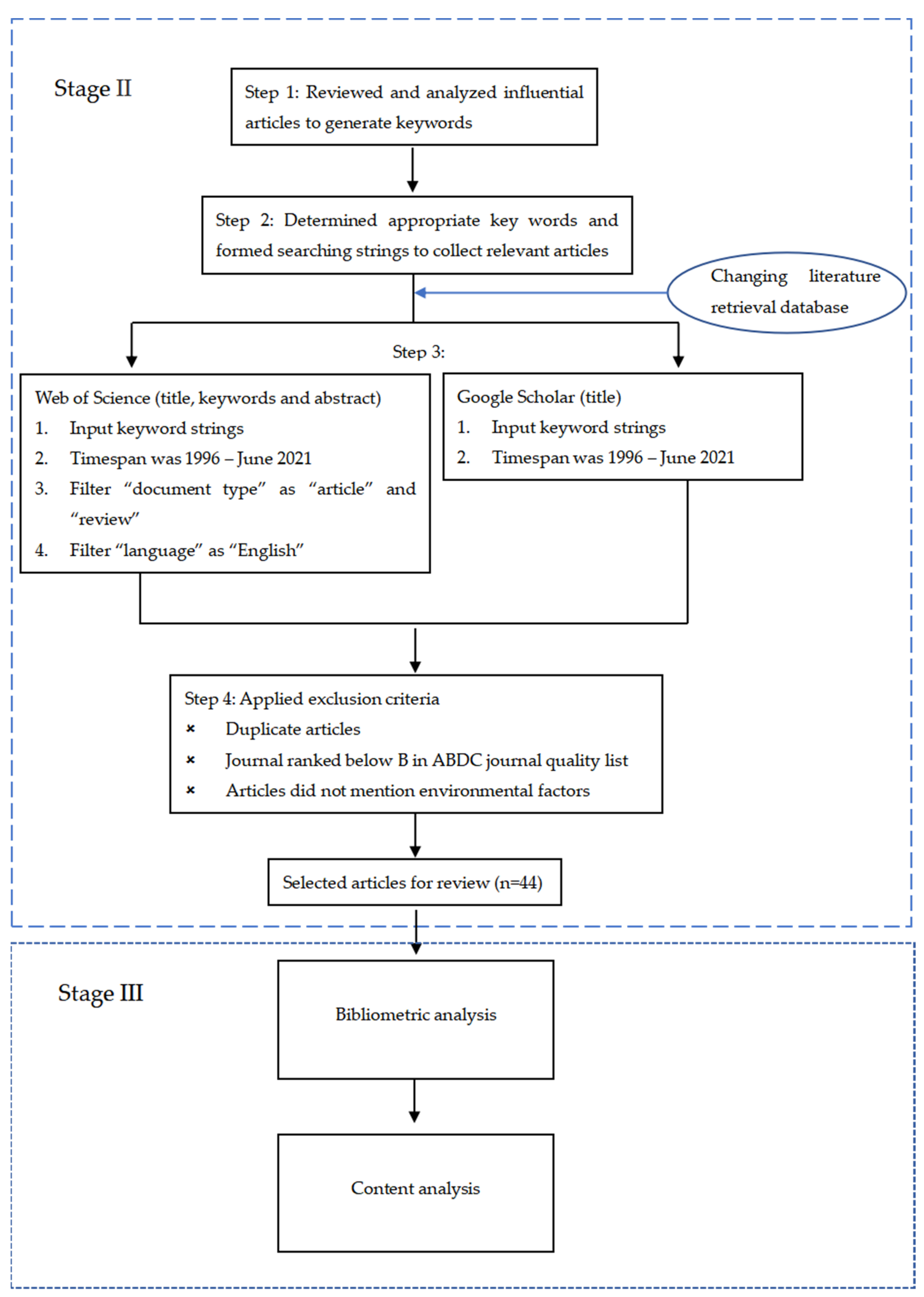

2. Methods

2.1. Stage I: Planning the Review

2.2. Stage II: Conducting the Review

2.3. Stage III: Reporting and Dissemination of Findings

3. Bibliometric Analysis

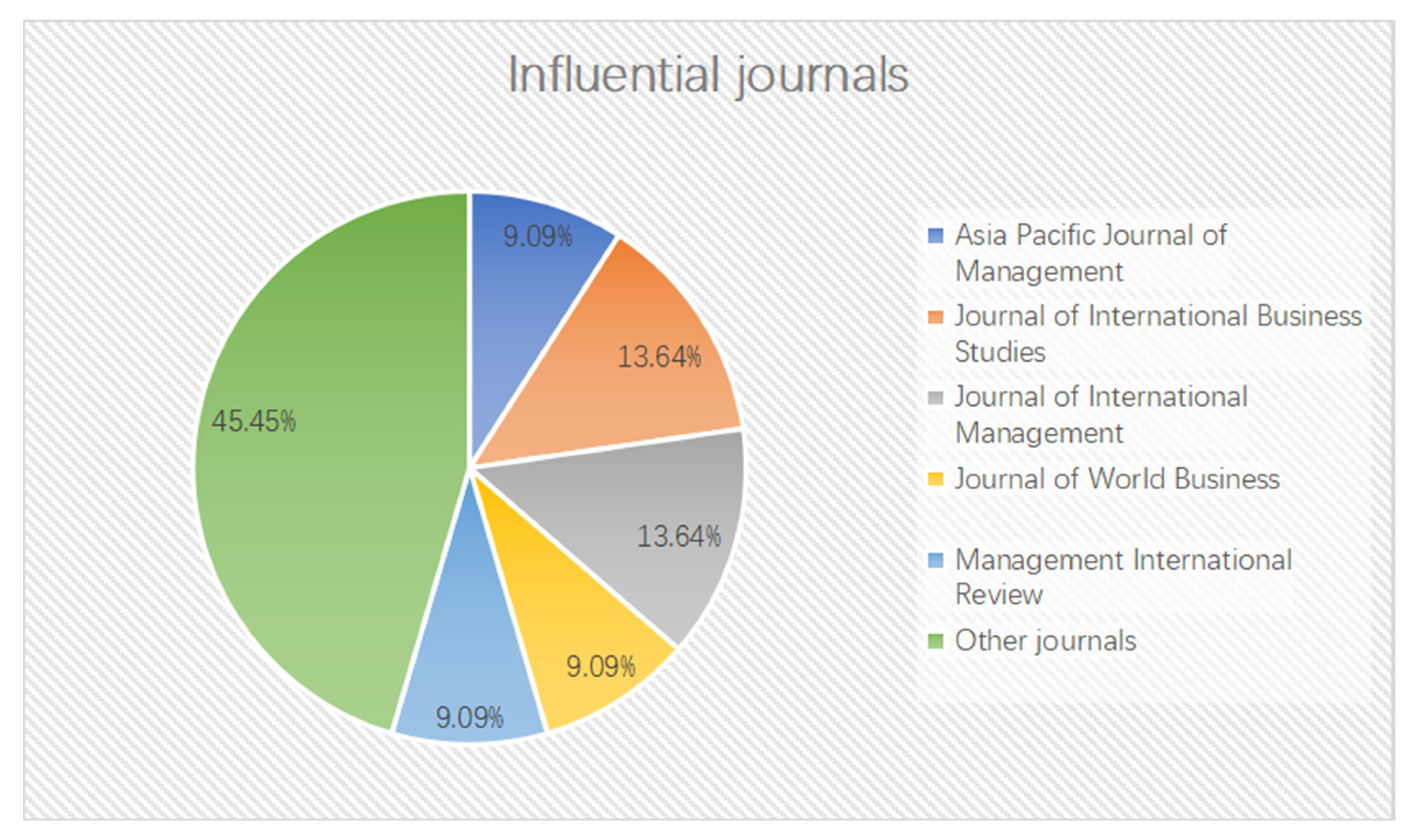

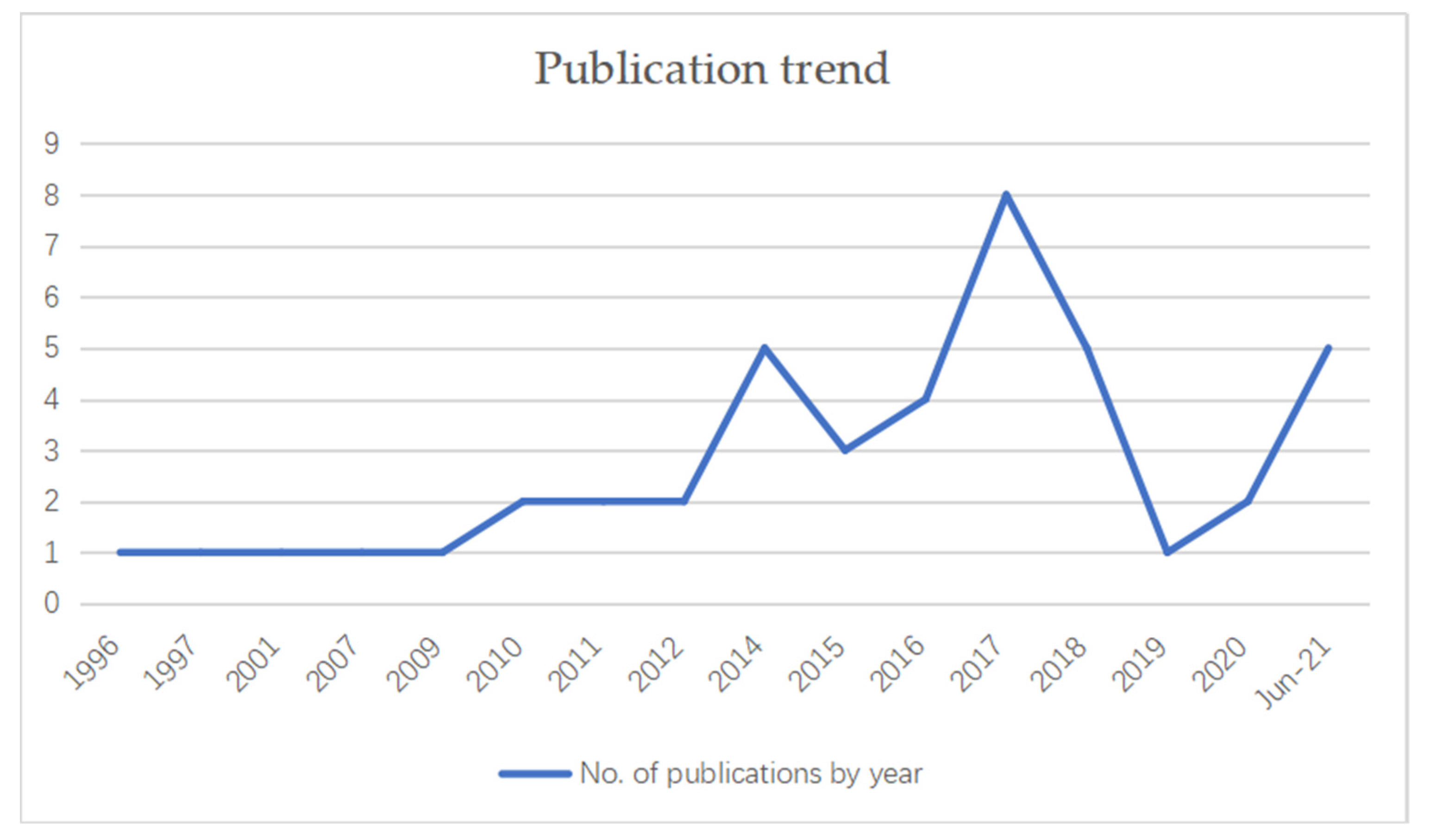

3.1. Journal and Year Distribution

3.2. Theories/Perspectives Used

3.3. Emerging Economies Have Been Studied

4. Content Analysis

4.1. Country-Level Factors

4.1.1. Cross-National Distance

4.1.2. Cultural Attributes

4.1.3. Government-Related Factors

4.1.4. Historical and Social Factors

4.2. Industry-Level Factors

4.2.1. Industry Conditions

4.2.2. Financial Indicators at Industry Level

4.2.3. Industrial Characteristics and Trends

4.2.4. Technological Level of Domestic Industries

5. Discussion and Future Research Direction

5.1. Varieties of Environmental Volatility Factors

5.2. Varieties of Emerging Economies

5.3. Varieties of Companies’ Scale

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahammad, Mohammad Faisal, Ziko Konwar, Nikolaos Papageorgiadis, Chengang Wang, and Jacob Inbar. 2018. R&D capabilities, intellectual property strength and choice of equity ownership in cross-border acquisitions: Evidence from BRICS acquirers in Europe. R & D Management 48: 177–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahsan, Mujtaba, and Martina Musteen. 2011. Multinational enterprises’ Entry Mode Strategies and Uncertainty: A Review and Extension. International Journal of Management Reviews 13: 376–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, Ilan, John Anderson, Ziaul Haque Munim, and Alice Ho. 2018. A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 35: 573–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athow, Brian, and Robert G Blanton. 2002. Colonial style and colonial legacies: Trade patterns in British and French Africa. Journal of Third World Studies 19: 219–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bhimani, Hardik, Anne-Laure Mention, and Pierre-Jean Barlatier. 2019. Social media and innovation: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144: 251–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, Vanessa P. G., Ilan Alon, Thelma Valéria Rocha, and Jefferson R. B. Galetti. 2021. International governance mode choice: Evidence from Brazilian franchisors. Journal of International Management 27: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, John. 2010. Evaluating the Evaluators: Media Freedom Indexes and What They Measure. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgcs_monitoringandeval_videos/1/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Chen, Kathy. 1994. China drafts measures to limit foreign investment in state assets. Wall Street Journal 18: A12, cited in Pan, Yigang. 1996. Influences on foreign equity ownership level in joint ventures in China. Journal of International Business Studies 27: 1–26. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Tain-Jy. 2006. Liability of foreignness and entry mode choice: Taiwanese firms in Europe. Journal of Business Research 59: 288–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ruiyuan, Lin Cui, Sali Li, and Robert Rolfe. 2017. Acquisition or Greenfield Entry Into Africa? Responding to Institutional Dynamics in an Emerging Continent. Global Strategy Journal 7: 212–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Shih-Fen S., and Jean-Francois Hennart. 2004. A hostage theory of joint ventures: Why do Japanese investors choose partial over full acquisitions to enter the United States? Journal of Business Research 57: 1126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, Ankita, Manish Popli, and Yi Li. 2021. Determinants of Equity Ownership Stake in Foreign Entry Decisions: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 23: 244–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhouni, Abdulrahman, Gwyneth Edwards, and Mehdi Farashahi. 2017. Psychic distance and ownership in acquisitions: Direction matters. Journal of International Management 23: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Yoona, Lin Cui, Yi Li, and Xizhou Tian. 2020. Focused and ambidextrous catch-up strategies of emerging economy multinationals. International Business Review 29: 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Chris Changwha, Simon Shufeng Xiao, Jeoung Yul Lee, and Jingoo Kang. 2016. The Interplay of Top-down Institutional Pressures and Bottom-up Responses of Transition Economy Firms on FDI Entry Mode Choices. Management International Review 56: 699–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Lin, and Fuming Jiang. 2012. State ownership effect on firms’ FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms. Journal of International Business Studies 43: 264–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, Lin, Di Fan, Xiaohui Liu, and Yi Li. 2017. Where to Seek Strategic Assets for Competitive Catch-up? A configurational study of emerging multinational enterprises expanding into foreign strategic factor markets. Organization Studies 38: 1059–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Maeseneire, Wouter, and Tine Claeys. 2012. SMEs, foreign direct investment and financial constraints: The case of Belgium. International Business Review 21: 408–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbag, Mehmet, Ekrem Tatoglu, and Keith W. Glaister. 2009. Equity-based entry modes of emerging country multinationals: Lessons from Turkey. Journal of World Business 44: 445–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbag, Mehmet, Martina McGuinness, and Hüseyin Altay. 2010. Perceptions of Institutional Environment and Entry Mode. Management International Review 50: 207–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, Douglas, Ilya R. P. Cuypers, and Gokhan Ertug. 2016. The effects of within-country linguistic and religious diversity on foreign acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies 47: 319–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driffield, Nigel, Tomasz Mickiewicz, and Yama Temouri. 2014. Institutions and Equity Structure of Foreign Affiliates. Corporate Governance-an International Review 22: 216–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dzikowski, Piotr. 2018. A bibliometric analysis of born global firms. Journal of Business Research 85: 281–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Kimberly M., Bruce T. Lamont, R. Michael Holmes, Sangbum Ro, Leon Faifman, Kaitlyn DeGhetto, and Heather Parola. 2018. Institutional determinants of ownership positions of foreign acquirers in Africa. Global Strategy Journal 8: 242–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaster, Christian, Manuel Portugal Ferreira, and Dan Li. 2021. The influence of generalized and arbitrary institutional inefficiencies on the ownership decision in cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, John, Ananda Mukherji, and Jyotsna Mukherji. 2009. Examining relational and resource influences on the performance of border region SMEs. International Business Review 18: 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, Nolan, Rusty Karst, and Jack Clampit. 2016. Emerging market MNE cross-border acquisition equity participation: The role of economic and knowledge distance. International Business Review 25: 267–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, Bernard Michael, and Elmar Lukas. 2006. The choice between greenfield investment and cross-border acquisition: A real option approach. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 46: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gubbi, Sathyajit R. 2015. Dominate or Ally? Bargaining Power and Control in Cross-Border Acquisitions by Indian Firms. Long Range Planning 48: 301–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, Mohamed Yacine, Adah-Kole Emmanuel Onjewu, Witold Nowiński, and Paul Jones. 2021. The determinants of SMEs’ export entry: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Business Research 125: 262–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Xia, Xiaohui Liu, Tianjiao Xia, and Lan Gao. 2018. Home-country government support, interstate relations and the subsidiary performance of emerging market multinational enterprises. Journal of Business Research 93: 160–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Yan, Xue-Feng Shao, Sang-Bing Tsai, Di Fan, and Wei Liu. 2021. E-Government and Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence From Chinese Cities. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM) 29: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, Witold J., and Andrew Delios. 2001. Uncertainty, imitation, and plant location: Japanese multinational corporations, 1990–1996. Administrative Science Quarterly 46: 443–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hensmans, Manuel, and Guangyan Liu. 2018. How Do the Normativity of Headquarters and the Knowledge Autonomy of Subsidiaries Co-Evolve? Capability-Upgrading Processes of Chinese Subsidiaries in Belgium. Management International Review 58: 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1980. Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization 10: 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtgrave, Maximilian, and Mert Onay. 2017. Success through trust, control, and learning? Contrasting the drivers of SME performance between different modes of foreign market entry. Administrative Sciences 7: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilhan-Nas, Tulay, Tarhan Okan, Ekrem Tatoglu, Mehmet Demirbag, Geoffrey Wood, and Keith W. Glaister. 2018. Board composition, family ownership, institutional distance and the foreign equity ownership strategies of Turkish MNEs. Journal of World Business 53: 862–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, Gavin, Robert Westwood, Nidhi Srinivas, and Ziauddin Sardar. 2011. Deepening, broadening and re-asserting a postcolonial interrogative space in organization studies. Organization 18: 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, Ben L., and Tsvetomira V. Bilgili. 2015. When history matters: The effect of historical ties on the relationship between institutional distance and shares acquired. International Business Review 24: 921–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyun Gon, Ajai S. Gaur, and Debmalya Mukherjee. 2020. Added cultural distance and ownership in cross-border acquisitions. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management 27: 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittilaksanawong, Wiboon. 2017. Institutional distances, resources and entry strategies Evidence from newly industrialized economy firms. International Journal of Emerging Markets 12: 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, Somnath. 2017. The moderating influence of market potential and prior experience on the governance quality-equity participation relationship Evidence from acquisitions in BRIC. Management Decision 55: 203–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, Somnath, B. Elango, and Sumit K. Kundu. 2014. Cross-border acquisition in services: Comparing ownership choice of developed and emerging economy MNEs in India. Journal of World Business 49: 409–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ruby P., Qimei Chen, Daekwan Kim, and Jean L. Johnson. 2008. Knowledge transfer between multinational corporations’ headquarters and their subsidiaries: Influences on and implications for new product outcomes. Journal of International Marketing 16: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peng-Yu, and Klaus E. Meyer. 2009. Contextualizing experience effects in international business: A study of ownership strategies. Journal of World Business 44: 370–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yi, Banruo Zhang, Di Fan, and Zijie Li. 2021. Digital media, control of corruption, and emerging multinational enterprise’s FDI entry mode choice. Journal of Business Research 130: 247–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Yanze, Axele Giroud, and Asmund Rygh. 2021. Emerging multinationals’ strategic asset-seeking M&As: A systematic review. International Journal of Emerging Markets 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Ru-Shiun, Mike Chen-ho Chao, and Alan Ellstrand. 2017a. Unpacking Institutional Distance: Addressing Human Capital Development and Emerging-Market Firms’ Ownership Strategy in an Advanced Economy. Thunderbird International Business Review 59: 281–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Rushiun, Kevin Lee, and Scott Miller. 2017b. Institutional impacts on ownership decisions by emerging and advanced market MNCs. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management 24: 454–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Ru-Shiun, Mike Chen-Ho Chao, and Monica Yang. 2016. Emerging economies and institutional quality: Assessing the differential effects of institutional distances on ownership strategy. Journal of World Business 51: 600–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaming, Na Yang, Linjie Li, and Yuanyuan Liu. 2021. Co-evolution of emerging economy MNEs and institutions: A literature review. International Business Review 30: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Fang-Yi. 2016. Factors leading to foreign subsidiary ownership: A multi-level perspective. Journal of Business Research 69: 5228–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jane Wenzhen, Wen Li, Aiqi Wu, and Xueli Huang. 2018. Political hazards and entry modes of Chinese investments in Africa. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 35: 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yadong, Huan Zhang, and Juan Bu. 2019. Developed country MNEs investing in developing economies: Progress and prospect. Journal of International Business Studies 50: 633–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yadong. 2001. Equity sharing in international joint ventures: An empirical analysis of strategic and environmental determinants. Journal of International Management 7: 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Tage Koed, and Per Servais. 1997. The internationalization of born globals: An evolutionary process? International Business Review 6: 561–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, Shige, and Kent E. Neupert. 2000. National culture, transaction costs, and the choice between joint venture and wholly owned subsidiary. Journal of International Business Studies 31: 705–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Shavin, and Ajai S. Gaur. 2014. Spatial geography and control in foreign acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies 45: 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Shavin, K. Sivakumar, and PengCheng Zhu. 2011. A comparative analysis of the role of national culture on foreign market acquisitions by US firms and firms from emerging countries. Journal of Business Research 64: 714–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Shavin, Xiaohua Lin, and Carlyle Farrell. 2016. Cross-national uncertainty and level of control in cross-border acquisitions: A comparison of Latin American and US multinationals. Journal of Business Research 69: 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Nobuhiro, and Ryosuke Okazawa. 2009. Colonial experience and postcolonial underdevelopment in Africa. Public Choice 141: 405–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjoen, Hans, and Stephen Tallman. 1997. Control and performance in international joint ventures. Organization Science 8: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moraes, Natália Valmorbida, Fernando Henrique Lermen, and Márcia Elisa Soares Echeveste. 2021. A systematic literature review on food waste/loss prevention and minimization methods. Journal of Environmental Management 286: 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morosini, Piero, Scott Shane, and Harbir Singh. 1998. National cultural distance and cross-border acquisition performance. Journal of International Business Studies 29: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschieri, Caterina, Roberto Ragozzino, and Jose Manuel Campa. 2014. Does regional integration change the effects of country-level institutional barriers on M&A? The case of the European Union. Management International Review 54: 853–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachum, Lilach, and Srilata Zaheer. 2005. The persistence of distance? The impact of technology on MNE motivations for foreign investment. Strategic Management Journal 26: 747–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, Paolo, and Elisabetta Raguseo. 2017. On the contingent value of IT-based capabilities for the competitive advantage of SMEs: Mechanisms and empirical evidence. Information & Management 54: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Minh Ha, and Quan Minh Quoc Binh. 2021. Entry Mode Choice of FDI Firms in Emerging Markets: An Evidence from Vietnam. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 57: 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øyna, Stine, Tamar Almor, B. Elango, and Shlomo Y. Tarba. 2018. Maturing born globals and their acquisitive behaviour. International Business Review 27: 714–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Yigang. 1996. Influences on foreign equity ownership level in joint ventures in China. Journal of International Business Studies 27: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Yigang, Lefa Teng, Atipol Bhanich Supapol, Xiongwen Lu, Dan Huang, and Zhennan Wang. 2014. Firms’ FDI ownership: The influence of government ownership and legislative connections. Journal of International Business Studies 45: 1029–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, Chinmay, Deeksha Singh, and Ajai S. Gaur. 2020. Home country learning and international expansion of emerging market multinationals. Journal of International Management, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Damon J., and Ezra W. Zuckerman. 2001. Middle-status conformity: Theoretical restatement and empirical demonstration in two markets. American Journal of Sociology 107: 379–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinto, Cláudia Frias, Manuel Portugal Ferreira, Christian Falaster, Maria Tereza Leme Fleury, and Afonso Fleury. 2017. Ownership in cross-border acquisitions and the role of government support. Journal of World Business 52: 533–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Penghua, Mengli Lv, and Yuping Zeng. 2020. R&D Intensity, Domestic Institutional Environment, and SMEs’ OFDI in Emerging Markets. Management International Review 60: 939–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Malika, and Yi Yang. 2007. Determinants of foreign ownership in international R&D joint ventures: Transaction costs and national culture. Journal of International Management 13: 110–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, Robert, and Byungchae Jin. 2008. Does knowledge spill to leaders or laggards? Exploring industry heterogeneity in learning by exporting. Journal of International Business Studies 39: 132–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalera, Vittoria, Debmalya Mukherjee, and Lucia Piscitello. 2020. Ownership strategies in knowledge-intensive cross-border acquisitions: Comparing Chinese and Indian MNEs. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 37: 155–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, Zhi, and Francisco Puig. 2018. Spatial Dependence of the FDI Entry Mode Decision: Empirical Evidence From Emerging Market Enterprises. Management International Review 58: 171–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, Bih-Lian, and Tzong-Chen Wu. 2012. Equity-based entry modes of the Greater Chinese Economic Area’s foreign direct investments in Vietnam. International Business Review 21: 508–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Sunny Li, Mike W. Peng, Bing Ren, and Daying Yan. 2012. A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M&As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs. Journal of World Business 47: 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpend, Regis, and Bryan Ashenbaum. 2012. The intersection of power, trust and supplier network size: Implications for supplier performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management 48: 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur-Wernz, Pooja, and Shantala Samant. 2019. Relationship between international experience and innovation performance: The importance of organizational learning for EMNEs. Global Strategy Journal 9: 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Chiung-Hui, and Ruby P. Lee. 2010. Host environmental uncertainty and equity-based entry mode dilemma: The role of market linking capability. International Business Review 19: 407–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Aiwei. 2009. The choice of market entry mode: Cross-border M&A or greenfield investment. International Journal of Business and Management 4: 239–45. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.688.2156&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Wang, Yanyu, Zhenzhen Xie, Wei Xie, and Jizhen Li. 2019. Technological capabilities, political connections and entry mode choices of EMNEs overseas R&D investments. International Journal of Technology Management 80: 149–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Yingqi, Bo Liu, and Xiaming Liu. 2005. Entry modes of foreign direct investment in China: A multinomial logit approach. Journal of Business Research 58: 1495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Jie, Nan Zhou, Seung Ho Park, Zaheer Khan, and Martin Meyer. 2021. The Role of FDI Motives in the Link between Institutional Distance and Subsidiary Ownership Choice by Emerging Market Multinational Enterprises. British Journal of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Zhenzhen, and Jiatao Li. 2017. Selective imitation of compatriot firms: Entry mode decisions of emerging market multinationals in cross-border acquisitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 34: 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Monica. 2015. Ownership participation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions by emerging market firms Antecedents and performance. Management Decision 53: 221–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Monica, and MaryAnne Hyland. 2012. Similarity in Cross-border Mergers and Acquisitions: Imitation, Uncertainty and Experience among Chinese Firms, 1985–2006. Journal of International Management 18: 352–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Xiaoli, and Mark Shanley. 2008. Industry determinants of the “merger versus alliance” decision. Academy of Management Review 33: 473–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yiu, Daphne, and Shige Makino. 2002. The choice between joint venture and wholly owned subsidiary: An institutional perspective. Organization Science 13: 667–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Jisun, Seung-Hyun Lee, and Kunsoo Han. 2015. FDI motives, market governance, and ownership choice of MNEs: A study of Malaysia and Thailand from an incomplete contracting perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32: 335–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, Srilata. 2002. The liability of foreignness, redux: A commentary. Journal of International Management 8: 351–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Gerard George. 2017. International entrepreneurship: The current status of the field and future research agenda. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating a New Mindset, 253–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Hongxin, Yadong Luo, and Taewon Suh. 2004. Transaction cost determinants and ownership-based entry mode choice: A meta-analytical review. Journal of International Business Studies 35: 524–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Nan. 2018. Hybrid state-owned enterprises and internationalization: Evidence from emerging market multinationals. Management International Review 58: 605–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Ying, and Deepak Sardana. 2020. Multinational enterprises’ risk mitigation strategies in emerging markets: A political coalition perspective. Journal of World Business 55: 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Journal Name | Number of Relevant Articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 4 |

| 2 | British Journal of Management | 1 |

| 3 | Corporate Governance—An International Review | 1 |

| 4 | Cross Cultural and Strategic Management | 2 |

| 5 | Emerging Markets Finance and Trade | 1 |

| 6 | Global Strategy Journal | 2 |

| 7 | International Business Review | 2 |

| 8 | International Journal of Emerging Markets | 1 |

| 9 | International Journal of Technology Management | 1 |

| 10 | International Marketing Review | 1 |

| 11 | Journal of Business Research | 3 |

| 12 | Journal of International Business Studies | 6 |

| 13 | Journal of International Management | 6 |

| 14 | Journal of World Business | 4 |

| 15 | Management Decision | 2 |

| 16 | Management International Review | 4 |

| 17 | Organization science | 1 |

| 18 | R & D Management | 1 |

| 19 | Thunderbird International Business Review | 1 |

| Total | 44 |

| Theories/Perspectives | Total Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Institution theory/institution-based view (IBV) | 34 | 36.56 |

| Transaction cost economics (TCE) | 18 | 19.35 |

| RBV/KBV/dynamic capabilities | 8 | 8.60 |

| Agency theory | 4 | 4.30 |

| Bargaining power theory | 4 | 4.30 |

| Information asymmetry | 3 | 3.23 |

| OLI model/eclectic paradigm | 3 | 3.23 |

| Organizational capability theory | 2 | 2.15 |

| Resource dependence theory | 2 | 2.15 |

| Springboard perspective | 2 | 2.15 |

| Contingency theory | 1 | 1.08 |

| Cultural/cultural distance theory | 1 | 1.08 |

| Social network theory | 1 | 1.08 |

| Stakeholder perspective | 1 | 1.08 |

| Uppsala model | 1 | 1.08 |

| Others | 8 | 8.60 |

| Total | 93 | 100 |

| Independent Variables | Reference |

|---|---|

| Cross-national distance | |

| Institutional distance | (Wu et al. 2021; Malhotra et al. 2016; Liou et al. 2016; Kedia and Bilgili 2015; Ellis et al. 2018; Pinto et al. 2017; Kittilaksanawong 2017; Lahiri et al. 2014; Yang 2015; Liou et al. 2017a; Scalera et al. 2020) |

| Cognitive distance | (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018; Liou et al. 2017b) |

| Normative distance | (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018; Liou et al. 2017b) |

| Regulative distance | (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2018; Liou et al. 2017b) |

| Cultural distance | (Malhotra et al. 2011; Malhotra et al. 2016; Yang 2015; Pan 1996; Demirbag et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2020; Tseng and Lee 2010) |

| Sociocultural distance | (Mjoen and Tallman 1997) |

| Linguistic distance | (Dow et al. 2016; Demirbag et al. 2009) |

| Religious distance | (Dow et al. 2016) |

| Geographic distance | (Malhotra and Gaur 2014) |

| Psychic distance | (Chikhouni et al. 2017) |

| Cultural attributes | |

| Home country power distance | (Richards and Yang 2007) |

| Level of linguistic diversity in the host country | (Dow et al. 2016) |

| Level of religious diversity in the host country | (Dow et al. 2016) |

| Government-related factors | |

| Relationship between home and host countries | (Demirbag et al. 2010) |

| Host country’s risk | (Richards and Yang 2007; Pan 1996; Demirbag et al. 2009; Demirbag et al. 2010; Moschieri et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2018; Tseng and Lee 2010; Bretas et al. 2021) |

| Host country’s environmental dynamism, complexity, hostility | (Luo 2001) |

| Host country’s digital media freedom | (Li et al. 2021) |

| Host country’s partner state ownership | (Pan 1996) |

| Host country’s market potential | (Nguyen and Binh 2021; Malhotra et al. 2011) |

| Host country’s market orientation | (Luo 2001) |

| Host country’s export orientation | (Luo 2001) |

| Host country’s government effectiveness | (Lahiri 2017; Driffield et al. 2014) |

| Host country’s corruption level | (Lahiri 2017; Driffield et al. 2014; Demirbag et al. 2010) |

| Host country’s law and order | (Lahiri 2017; Driffield et al. 2014; Demirbag et al. 2010) |

| Host country’s institutional environment | (Chen et al. 2017; Pan et al. 2014; Falaster et al. 2021) |

| Host country’s legal requirements | (Mjoen and Tallman 1997) |

| Host country’s strength of IP institutions | (Ahammad et al. 2018) |

| Host country’s regulatory restrictions | (Cui and Jiang 2012) |

| Home country’s government pressure | (Chung et al. 2016) |

| Home country’s government support | (Pinto et al. 2017) |

| Home country’s regulatory restrictions | (Cui and Jiang 2012) |

| Host country’s factor market | (Chen et al. 2017) |

| Foreign origin and industry clusters | (Shen and Puig 2018) |

| Historical and social factors | |

| Colonial ties | (Ellis et al. 2018) |

| Host country’s fractionalization | (Ellis et al. 2018) |

| Independent Variables | Reference |

|---|---|

| Industry conditions | |

| Competitive intensity | (Pan 1996) |

| Industry relatedness | (Ahammad et al. 2018; Yang 2015) |

| Market turbulence | (Tseng and Lee 2010) |

| Financial indicators at industry-level | |

| Local purchasing for production inputs | (Yu et al. 2015) |

| Local market for its sales | (Yu et al. 2015) |

| Large capital requirements | (Nguyen and Binh 2021) |

| Industrial characteristics and trends | |

| Industry experiences by peer firms | (Xie and Li 2017) |

| Imitation power | (Yang and Hyland 2012) |

| Technological level of domestic industries | |

| Home country industry technological capabilities | (Wang et al. 2019) |

| Research Gaps in Extant Studies | Reasons | Future Research Direction | Drivers | Future Prospect Offered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of research on external environmental factors | 1. Scholars mainly focused on DMNEs in the past because DMNEs dominated the international market. 2. The external environment was relatively stable in the past decades. | Varieties of environmental volatility factors | 1. EMNEs play an increasingly important role in the global economy. 2. The international environment has become complex and turbulent in recent years. | 1. Longitudinal research provides valuable opportunities to explore some exciting research questions. 2. Research on dynamic environmental volatility factors provides a deeper understanding of the influences. 3. Makes the studies more dynamic and comprehensive, facilitating the development of extant theories. |

| Lack of research on EMNEs from less concerning emerging economies | The internationalization of EMNEs from dominant emerging economies (e.g., BRICs) is more proactive and taking an increasing share in international business. | Varieties of emerging economies | Environmental factor changes in the volatile circumstances will have different impacts on different economies. | 1. Helps scholars to further understand the similarities and differences of the relationship between the environmental factors and EMNEs’ entry mode choice in different economies. 2. Help scholars better understand the boundary conditions of environmental factors affect EMNEs’ entry mode decision-making under volatile circumstances. |

| Lack of research on SMEs | 1.Large EMNEs are the dominant participants in international business. 2. The data of listed companies are easier to obtain. | Varieties of companies’ scale | 1. SMEs are expected to have heterogeneous risk preferences, impacting entry mode choice. 2. SMEs might be more flexible under a new environment. 3. The international expansion of SMEs from emerging economies has become an important phenomenon in the international market. 4. Born global firms as a specific category of SMEs that deserves more attention. | 1. Help scholars understand the similarities and differences of the environmental drivers on enterprises of different sizes. 2. Enables researchers to extend relevant theories regarding environmental factors that affect SMEs’ entry mode choice under turbulent circumstances. 3. Provides scholars with great opportunities to develop theories which might be more suitable for the internationalization of SMEs from emerging economies. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Gao, R.; Wang, J. Determinants of EMNEs’ Entry Mode Decision with Environmental Volatility Issues: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100500

Li Y, Gao R, Wang J. Determinants of EMNEs’ Entry Mode Decision with Environmental Volatility Issues: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(10):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100500

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yameng, Ruosu Gao, and Jingyi Wang. 2021. "Determinants of EMNEs’ Entry Mode Decision with Environmental Volatility Issues: A Review and Research Agenda" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 10: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100500

APA StyleLi, Y., Gao, R., & Wang, J. (2021). Determinants of EMNEs’ Entry Mode Decision with Environmental Volatility Issues: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(10), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100500