Double Taxation Treaties as a Catalyst for Trade Developments: A Comparative Study of Vietnam’s Relations with ASEAN and EU Member States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- Those identified as residents of a country must fulfil their tax obligations in that country for all of their income regardless of the sources of income;

- (ii)

- Those identified as non-residents of a country must fulfil their tax obligations for all of their incomes arising therein. Methods to identify residents and sources of income vary across nations, and in some circumstances, a business entity or individual may be a resident of two or more countries. Double taxation could, therefore, be present in several means, for example, two or more countries may levy taxes on the global income of a single taxpayer, who is identified as the resident of these countries. In another case, a taxpayer’s income which is recognized to generate in the territory of multiple countries must be taxed jointly by the related governments.

2. Impact of Double Taxation Treaties: What Does Literature Say?

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Empirical Evidence

3. Vietnam’s Tax Treaty Signing Situation and Trade Activities with ASEAN

3.1. Vietnam’s Tax Treaty Signing Situation

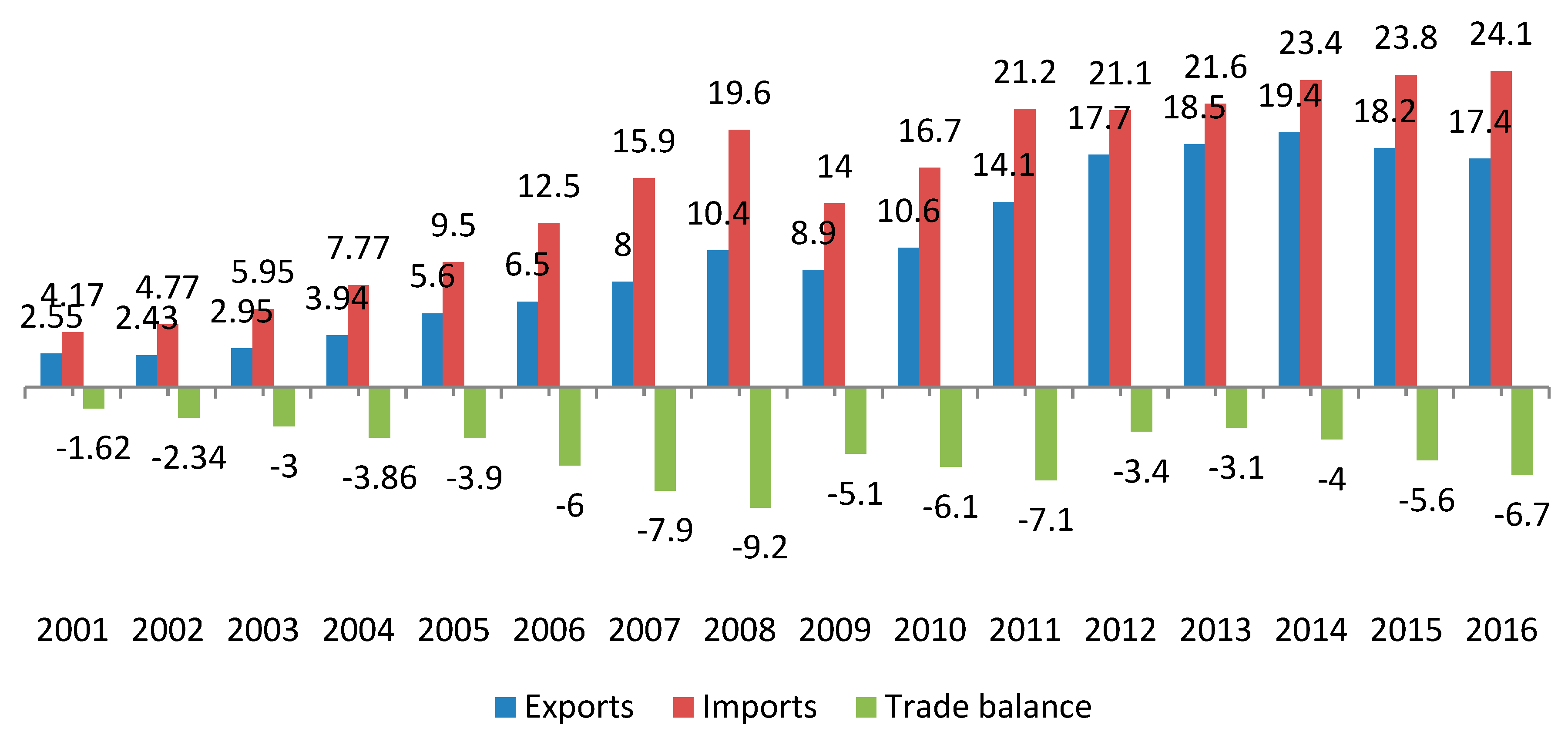

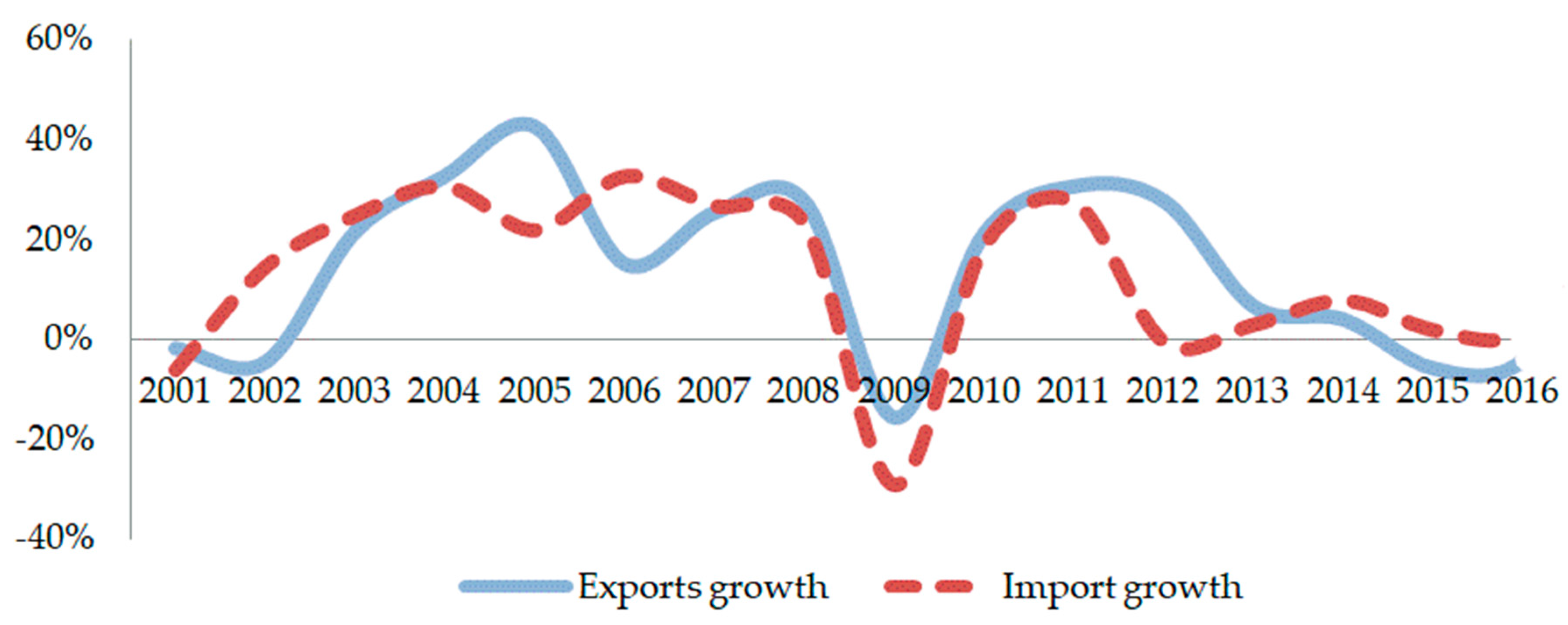

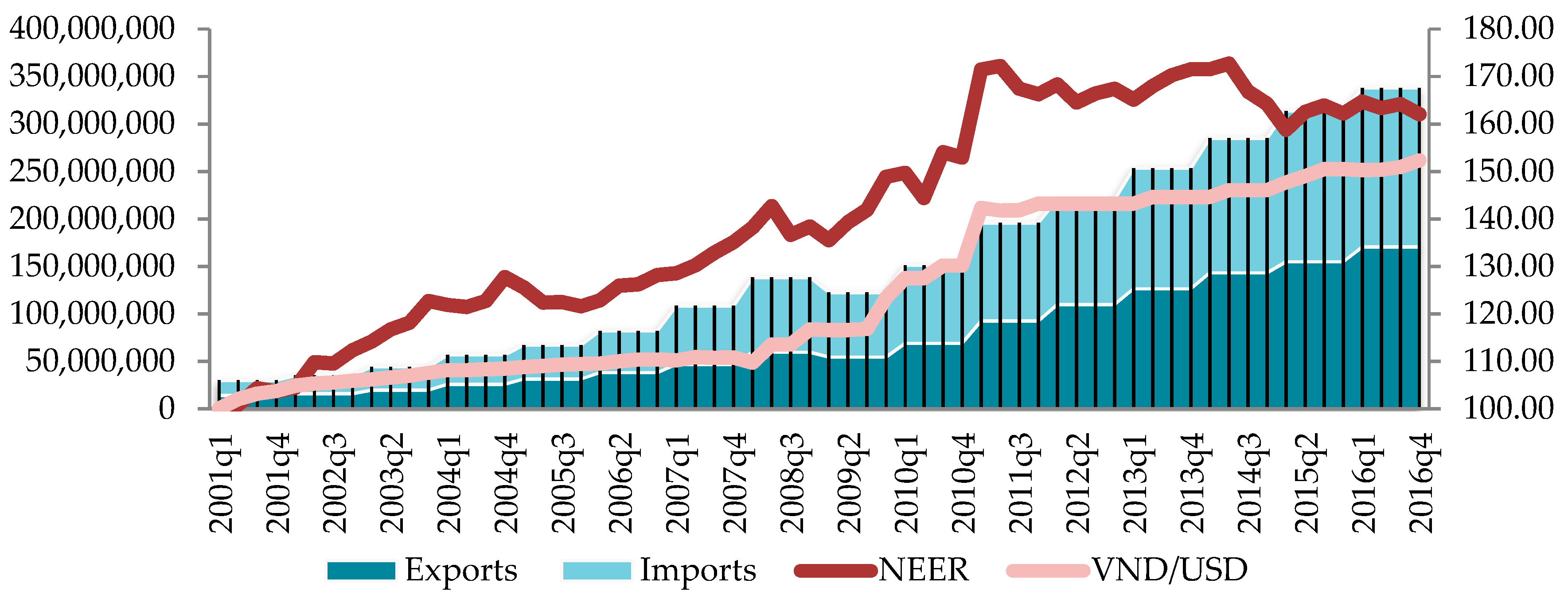

3.2. Bilateral Trade between Vietnam and ASEAN during 2001–2016

4. Methodology

4.1. Gravity Equations

- -

- lnYi,t and lnYj,t: denote logs of the per capita GDP of Vietnam and country j at time t, respectively (in constant 2010 USD);

- -

- lnNj,t: refers to a log of the population of country j at time t. It is noteworthy that both Yj and Nj indicators showcase the market capacity of the trading partner;

- -

- lnDij: is the log of great circle distance1 (in kilometres) between the capital cities of Vietnam and country j, which represents the trade costs of Vietnam;

- -

- lnReri/j,t: denotes the log of real exchange rate of VND (Vietnamese dong) against trading partner j’s currency, measured based on the nominal exchange rate adjusted for the effect of the price index. The formula for this indicator is as follows.where Neri/$ and Nerj/$ are the nominal exchange rate of VND and j’s currency vis-à-vis USD, i.e., the value of each currency in exchange for a single dollar; CPIi and CPIj refer to the consumer price index of Vietnam and country j. For each pair of countries, the Rer is normalized by setting 2001 as the base year (2001=100). Besides, it is worth noting that a rise in the Reri/j refers to the depreciation of VND against partner currency;

- -

- Border: a dummy variable capturing the border effect, taking the value of 1 if Vietnam and j share a common land border, 0 otherwise;

- -

- Landlockedj: a dummy variable for landlocked trading partner, taking the value of 1 if country j does not have direct access to the sea, 0 otherwise. In theory, being entirely enclosed by land would be detrimental to these partner countries in developing international trade by sea, thereby inhibiting their economic development;

- -

- Bloc: a set of dummies representing the regional trade agreement effect, which encompass three separate cases as follows.

- ASEAN: receives the value of 1 if country j is a member of ASEAN and participates in ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), 0 otherwise;

- ASEAN+3: receives the value of 1 if country j join the comprehensive partnership agreement between ASEAN and the ‘plus three’ nations, namely, China, Japan and Republic of Korea, 0 otherwise;

- EU: receives the value of 1 if country j is a member of the EU, 0 otherwise;

- -

- Dttij,t: a dummy variable denoting the existence of tax treaty, taking the value of 1 if country j has successfully concluded the double taxation treaty with Vietnam, 0 otherwise;

- -

- t denotes for the time.

- -

- Bloc × Dttij,t: denotes the interaction term between trade bloc and tax treaty;

- -

- Other variables are in Equation (2).

4.2. Data

- -

- Data on bilateral trade volume (including exports and imports) of Vietnam with each trading partner are collected from the International Trade Center (ITC) database;

- -

- Data on per capita GDP and population are extracted from the World Development Indicators (WDI);

- -

- Distance between trading partners is calculated based on the ‘great circle distance between capital cities’ database (www.chemical-ecology.net).

- -

- Data on exchange rate of each currency against USD and CPI—Consumer Price Index (used to work out the real exchange rate) are obtained from the International Financial Statistics (IFS).

- -

- Data on the membership of AFTA, ASEAN+3 and the EU are recorded from the official websites of these organisations (asean.org and europa.eu). The list of double taxation treaties of Vietnam is updated from the website of Vietnam’s General Department of Taxation (www.gdt.gov.vn).

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Empirical Results

- (i)

- the per capita incomes of Vietnam and its partners.

- (ii)

- the population of the partner countries.

- (iii)

- the downfall of VND, could foster the bilateral trade of Vietnam. Such positive tendency is also reflected through the effect of both sharing a common border and signing a double taxation treaty.

5.2. Discussions

- -

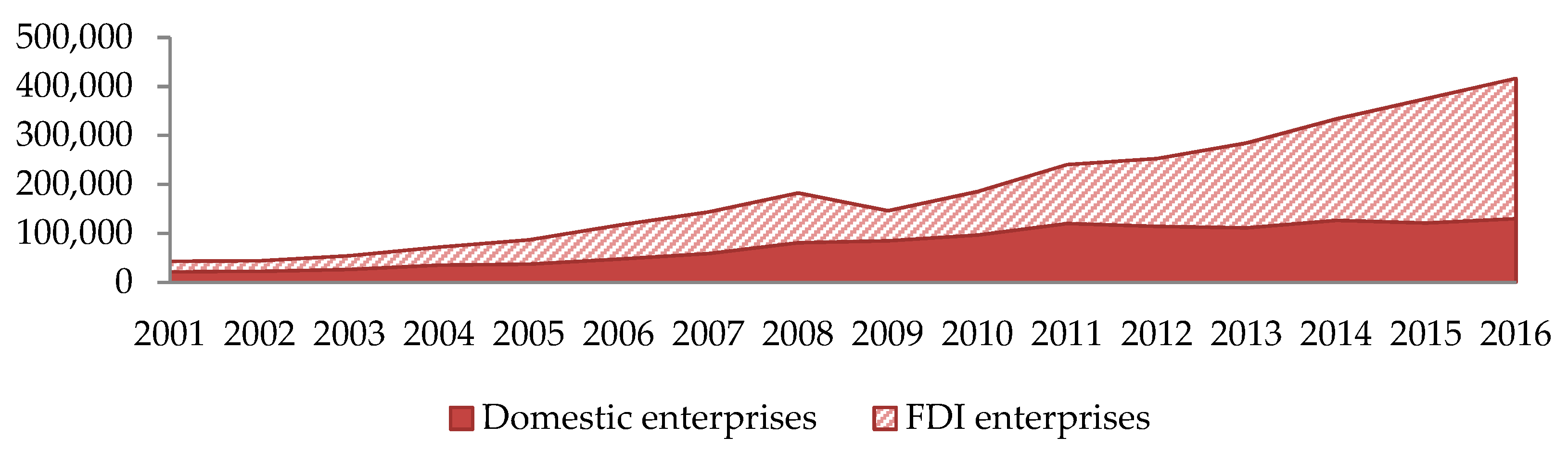

- According to Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) statistics, the period of 2011–2016 saw a marked increase in the proportion of foreign-invested enterprises whose report losses (to relieve the tax burden), of which the net loss margin of wholly foreign-invested enterprises always outweighs that of joint venture enterprises (Figure 5 will provide an overview on shares of domestic and foreign dỉrect investment enterprises to trade volume of Vietnam, and Table 6 will give a snapshot of the business performance of FDI enterprises in Vietnam from 2001–2016 due to a limited data source and assessment). This situation arises since, in comparison to other developing economies, Vietnam’s tax treaties tend to safeguard its taxing right to a higher degree against developed countries from ASEAN or the EU3.

- -

- In principle, in order to record a net loss in the income statement, foreign-invested enterprises may be in “cahoots” with their foreign affiliation under common ownership or control to increase the cost of importing materials and/or reduce the export price. Alongside the preferential treatment brought by tax treaties, some accounting adjustment of foreign-invested enterprises, for instance, to increase the input costs and/or lower export revenues, may result in (i) the ‘imports dominance’ effect and (ii) net losses in business. Under the circumstances, enterprises have benefitted from ‘double non-taxation’. A report by IMF (2019) showes that the MNEs can “shift their profits to lower tax jurisdiction” if the developing countries have not much experienced and effective provision to protect against. Somehow, developing with less power negotiation will accept the bilateral tax treaties—even that country cannot benefit from the agreement—due to economic reason such as increasing FDI inflow or diplomatic issues (see more detail in Zolt 2018; IMF 2014, 2019; OECD 2015).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Action Aid. 2017. Double Taxation Treaties in Vietnam: Red Carpet for Whom? Available online: actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/policy_brief_new_1_0.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Azémar, Céline, and Andrew Delios. 2008. Tax competition and FDI: The special case of developing countries. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 22: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Paul L. 2014. An analysis of double taxation treaties and their effect on foreign direct investment. International Journal of the Economics of Business 21: 341–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuta-Misu, Nicoleta, and Florin Tudor. 2010. The International Double Taxation—Causes and avoidance. Acta Universitatis Danubius Economica 5: 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel, Fabrian, Matthias Busse, and Eric Neumayer. 2010. The impact of double taxation treaties on foreign direct investment: Evidence from large dyadic panel data. Contemporary Economic Policy 28: 366–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, Jeffrey H. 1985. The Gravity Equation in International Trade: Some Microeconomic Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics 67: 474–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, Bruce A. 2005. A review of the empirical literature on FDI determinants. Atlantic Economic Journal 33: 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Julia, and Daniel Fuentes. 2014. A Legal and Economic Analysis of Double Taxation Treaties between Austria and Developing Countries. Wien: Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC). [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Julia, and Martin Zagler. 2014. An Economic Perspective on Double Tax Treaties with(in) Developing Countries. World Tax Journal 6: 242–81. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Julia, and Martin Zagler. 2017. The true art of the tax deal: Evidence on aid flows and bilateral double tax agreement. The World Economy 41: 1478–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunschweig, Anna. 2014. Double Taxation Treaties’ Impact on International Trade. Master’s Thesis, Lund University School of Economics & Management, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Carrère, Cèline. 2006. Revisiting the effects of regional trade agreements on trade flows with proper specification of the gravity model. European Economic Review 50: 223–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, Rosa F. 2004. The Relationship between Foreign Direct Investment and International Trade Substitution or Complementarity? A Survey. Porto: CETE, Universidade do Porto. [Google Scholar]

- Fukase, Emiko, and Will Martin. 1999. A Quantitative Evaluation of Vietnam’s Accession to the ASEAN Free Trade Area. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2220. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2014. Spillovers in International Corporate Taxation. IMF Policy Paper, 050914. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/050914.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2019. Corporate Taxation in the Global Economy. IMF Policy Paper, 2019007. Available online: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/PP/2019/PPEA2019007.ashx (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Kadet, Jeffery M. 2016. BEPS: A Primer on Where It Came from and Where It’s Going. Tax Notes 150: 793. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2739659 (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Kahouli, Bassem, and Anis Omri. 2017. Foreign direct investment, foreign trade and environment: New evidence from simultaneous-equation system of gravity models. Research in International Business and Finance 42: 353–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limão, Nuno, and Anthony J. Venables. 2001. Infrastructure, geographical disadvantage, transport costs, and trade. World Bank Economic Review 15: 451–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Marc A. 1979. The effects of devaluation on the trade balance and the balance of payments: Some new results. Journal of Political Economy 87: 600–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Angharad, and Lynne Oats. 2016. Principles of International Taxation, 5th ed. West Sussex: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Quynh Huy. 2018. Determinants of Vietnam’s Exports: An Application of the Gravity Model. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 25: 103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nho, Pham V., Dao Ngoc Tien, and Doan Quang Hung. 2014. Analyzing the Determinants of Services Trade Flows between Vietnam and European Union: Gravity Model Approach. MPRA Paper, 63995. Munich: Munich Personal RePEc Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, Dennis. 2013. International Trade without CES: Estimating Translog Gravity. Journal of International Economics 89: 271–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2015. Preventing the Artificial Avoidance of Permanent Establishment Status, Action 7—2015 Final Report. OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. Paris: OECD Publishing, Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241220-en (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2017. Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Mogens. 2011. International Double Taxation. Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer Law International. [Google Scholar]

- Sattinger, Michael. 1978. Trade Flows and Differences between Countries. Atlantic Economic Journal 6: 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, Jan. 1962. Shaping the World Economy: Suggestions for an International Economic Policy. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bergeijk, Peter A. G., and Steven Brakman. 2010. The Gravity Model in International Trade: Advances and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Dennis, and Mordechai E. Kreinin. 1983. Determinants of international trade flows. Review of Economics and Statistics 65: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolt, Eric M. 2018. Tax Treaties and Developing Countries. Forthcoming in 72 Tax Law Review; UCLA School of Law, Law-Econ Research Paper No. 18-10. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3248010 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

| 1 | The minimum geographical distance on the surface of the earth. |

| 2 | The central reference rate is pegged to three benchmarks: (i) demand and supply of VND; (ii) the exchange rates for a basket of 8 major trading partner currencies, including USD, EUR, CNY, THB, JPY, SGD, KRW and TWD; (iii) adjustments to balance macroeconomic needs. |

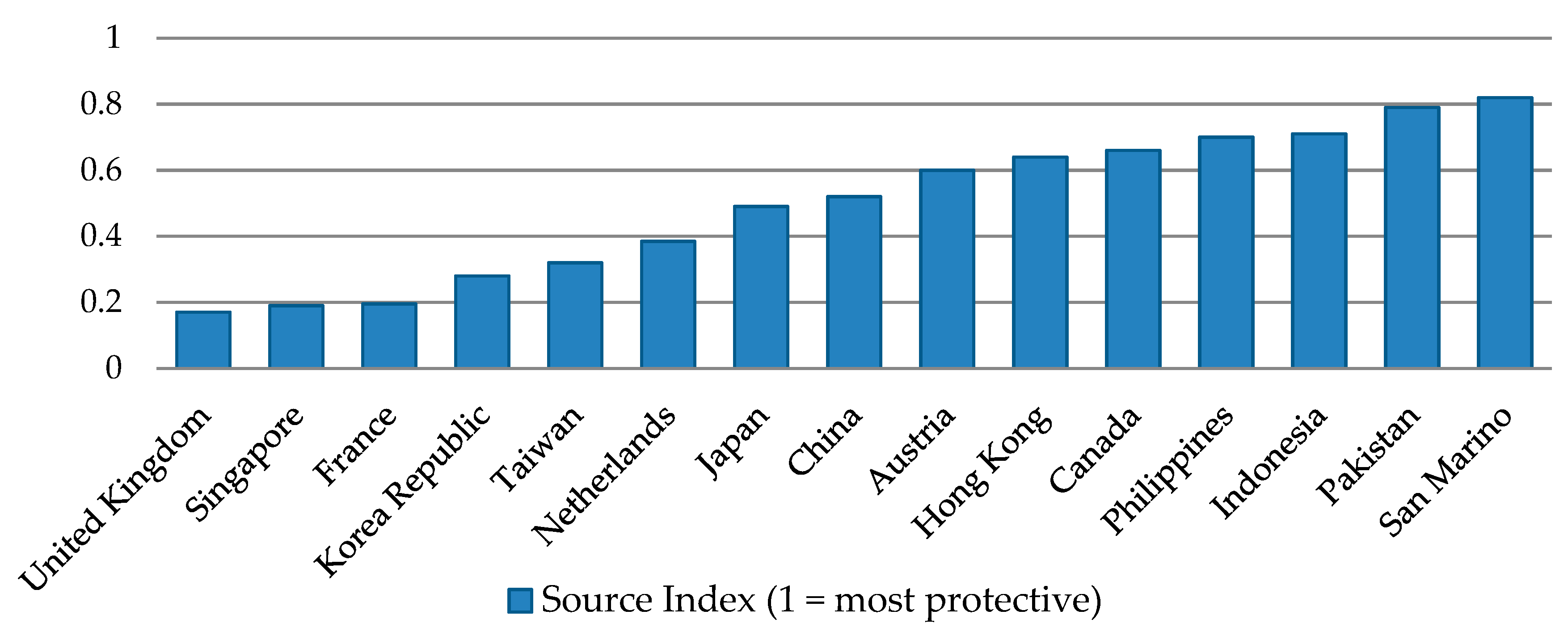

| 3 | Based on Action Aid’s (2017) calculations, Vietnam’s average source index reaches 0.56 while the average across all developing countries is just 0.45. |

| No. | Double Taxation Treaty | Signing Date | Effective Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vietnam–Thailand | 23 December 1992 | 29 December 1992 |

| 2 | Vietnam–Singapore * | 2 March 1994 | 9 September 1994 |

| 12 September 2012 | 11 January 2013 | ||

| 3 | Vietnam–Malaysia | 7 September 1995 | 13 August 1996 |

| 4 | Vietnam–Laos | 14 January 1996 | 30 September 1996 |

| 5 | Vietnam–Indonesia | 22 December 1997 | 10 February 1999 |

| 6 | Vietnam–Myanmar | 12 May 2000 | 12 August 2003 |

| 7 | Vietnam–Philippines | 14 November 2001 | 29 September 2003 |

| 8 | Vietnam–Brunei | 16 August 2007 | 1 January 2009 |

| Variables | Unit | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral trade between Vietnam and j (Tij) | USD thousand | 2,276,979 | 6,173,491 | 20 | 7.20 × 107 |

| Exports from Vietnam to j (Xij) | USD thousand | 1,092,218 | 2,896,238 | 10 | 3.85 × 107 |

| Imports from j into Vietnam (Mij) | USD thousand | 1,184,762 | 3,942,454 | 3 | 5.00 × 107 |

| GDP per capita of Vietnam (Yi) | USD | 1233 | 285 | 800 | 1735 |

| GDP per capita of j (Yj) | USD | 26,717 | 22,364 | 382 | 111,968 |

| Population of j (Nj) | People | 7.42 × 107 | 2.17 × 108 | 284,968 | 1.38 × 109 |

| Distance between Vietnam and j (Dij) | km | 7328 | 3931 | 482 | 18,958 |

| Real exchange rate of VND per foreign currency (Reri/j) | 383 | 2470 | 1.97 | 31,947 | |

| Border effect (Border) | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 | |

| Landlocked country (Landlockedj) | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | |

| Trade bloc (Bloc) | Including 3 dummies as follows. | ||||

| • ASEAN | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | |

| • ASEAN+3 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | |

| • EU | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Tax treaty effect (Dttij) | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Explanatory Variables | ASEAN | ASEAN+3 | EU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | |

| lnYi | 2.82 *** | 2.80 *** | 2.84 *** | 2.83 *** | 2.83 *** | 2.86 *** |

| lnYj | 1.06 *** | 1.07 *** | 1.02 *** | 1.02 *** | 1.02 *** | 1.02 *** |

| lnNj | 1.03 *** | 1.02 *** | 1.01 *** | 1.00 *** | 1.01 *** | 1.01 *** |

| lnDij | −1.17 *** | −1.16 *** | −1.20 *** | −1.19 *** | −1.33 *** | −1.37 *** |

| lnReri/j | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.21 *** |

| Border | 1.14 *** | 1.31 *** | 0.98 *** | 1.06 *** | 1.08 *** | 1.07 *** |

| Landlocked | −0.36 ** | −0.39 *** | −0.34 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.42 *** |

| Bloc | 0.62 *** | 0.15 | 0.45 *** | 0.13 | −0.05 | −0.31 ** |

| Dttij | 0.24 ** | 0.20 * | 0.25 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.31 *** | 0.15 |

| Bloc×Dttij | 0.60 ** | 0.37 | 0.46 ** | |||

| Explanatory Variables | ASEAN | ASEAN+3 | EU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | |

| lnYi | 3.18 *** | 3.18 *** | 3.19 *** | 3.21 *** | 3.11 *** | 3.12 *** |

| lnYj | 0.97 *** | 0.97 *** | 0.92 *** | 0.92 *** | 0.89 *** | 0.89 *** |

| lnNj | 1.06 *** | 1.06 *** | 1.03 *** | 1.04 *** | 1.06 *** | 1.06 *** |

| lnDij | −0.84 *** | −0.84 *** | −0.93 *** | −0.94 *** | −1.14 *** | −1.16 *** |

| lnReri/j | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.24 *** |

| Border | 1.30 *** | 1.24 *** | 1.11 *** | 1.00 *** | 1.17 *** | 1.17 *** |

| Landlocked | −0.28 * | −0.27 * | −0.26 * | −0.24 | −0.40 ** | −0.44 *** |

| Bloc | 0.85 *** | 0.99 *** | 0.43 ** | 0.87 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.15 |

| Dttij | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.20 * | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| Bloc×Dttij | −0.18 | −0.50 | 0.31 | |||

| Explanatory Variables | ASEAN | ASEAN+3 | EU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (2) | Equation (4) | |

| lnYi | 2.31 *** | 2.26 *** | 2.33 *** | 2.30 *** | 2.35 *** | 2.37 *** |

| lnYj | 1.45 *** | 1.47 *** | 1.40 *** | 1.39 *** | 1.40 *** | 1.40 *** |

| lnNj | 1.14 *** | 1.13 *** | 1.11 *** | 1.09 *** | 1.11 *** | 1.11 *** |

| lnDij | −1.47 *** | −1.44 *** | −1.51 *** | −1.50 *** | −1.67 *** | −1.70 *** |

| lnReri/j | 0.18 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.22 *** |

| Border | 1.59 *** | 2.02 *** | 1.35 *** | 1.61 *** | 1.52 *** | 1.51 *** |

| Landlocked | −0.42 ** | −0.49 *** | −0.38 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.41 ** |

| Bloc | 0.93 *** | −0.25 | 0.68 *** | −0.28 | −0.25 * | −0.40 ** |

| Dttij | 0.58 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.71 *** | 0.61 *** |

| Bloc×Dttij | 1.51 *** | 1.11 *** | 0.28 | |||

| Time | Percentage of Enterprises Raising Investment Capital | Percentage of Enterprises with Increased Labour Force | Percentage of Enterprises Reporting Profits | Percentage of Enterprises Reporting Losses | Average Total Revenue (Millions of USD, Constant 2010 Prices) | Average Total Cost (Millions of USD, Constant 2010 Prices) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 4.8 | 28.4 | 57.7 | 24.8 | 1.36 | 1.08 |

| 2012 | 5.2 | 31.0 | 60.4 | 27.5 | 1.54 | 0.97 |

| 2013 | 5.1 | 30.0 | 63.6 | 24.1 | 1.45 | 0.94 |

| 2014 | 16.1 | 62.4 | 57.9 | 34.2 | 1.14 | 0.71 |

| 2015 | 11.4 | 62.4 | 55.1 | 37.6 | 0.69 | 1.42 |

| 2016 | 11.0 | 63.3 | 59.0 | 33.4 | 0.73 | 0.49 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pham, A.D.; Pham, H.; Ly, K.C. Double Taxation Treaties as a Catalyst for Trade Developments: A Comparative Study of Vietnam’s Relations with ASEAN and EU Member States. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2019, 12, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040172

Pham AD, Pham H, Ly KC. Double Taxation Treaties as a Catalyst for Trade Developments: A Comparative Study of Vietnam’s Relations with ASEAN and EU Member States. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2019; 12(4):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040172

Chicago/Turabian StylePham, Anh D., Ha Pham, and Kim Cuong Ly. 2019. "Double Taxation Treaties as a Catalyst for Trade Developments: A Comparative Study of Vietnam’s Relations with ASEAN and EU Member States" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12, no. 4: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040172

APA StylePham, A. D., Pham, H., & Ly, K. C. (2019). Double Taxation Treaties as a Catalyst for Trade Developments: A Comparative Study of Vietnam’s Relations with ASEAN and EU Member States. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(4), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040172