Prevalence and Antimicrobial-Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pools and Hot Tubs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial Isolation and Confirmation with PCR

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

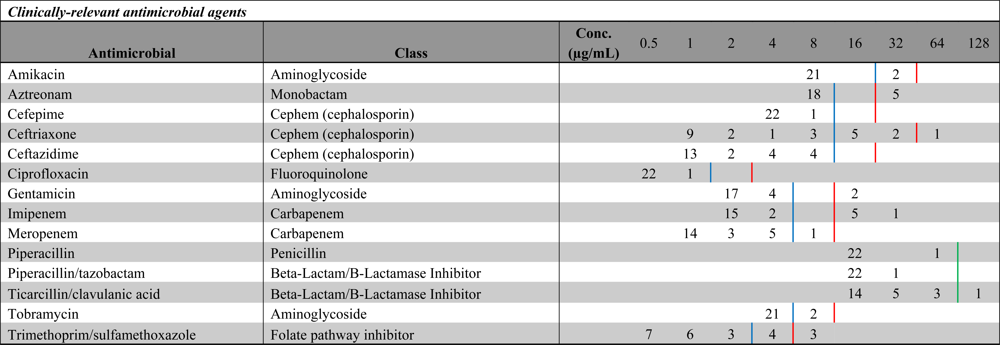

3. Results and Discussion

Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Bodey, GP; Bolivar, R; Fainstein, V; Jadeja, L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis 2008, 5, 279–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K; Iwai, S; Kumasaka, K; Horikoshi, A; Inada, S; Inamatsu, T; Ono, Y; Nishiya, H; Hanatani, Y; Narita, T; Sekino, H; Hayashi, I. Survey of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the Tokyo Johoku Association of Pseudomonas Studies. J. Infect. Chemother 2001, 7, 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Aeschlimann, J. The role of multidrug efflux pumps in the antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, PD; Wolter, DJ; Hanson, ND. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2009, 22, 582–610. [Google Scholar]

- Strateva, T; Yordanov, D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa—A phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J. Med. Microbiol 2009, 58, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Gales, AC; Jones, RN; Turnidge, J; Rennie, R; Ramphal, R. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates: occurrence rates, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and molecular typing in the global SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis 2001, 32, S146–S155. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, Y; Troillet, N; Karchmer, AW; Samore, MH. Health and economic outcomes of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Intern. Med 1999, 159, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Zichichi, L; Asta, G; Noto, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa folliculitis after shower/bath exposure. Int. J. Dermatol 2000, 39, 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Berrouane, YF; McNutt, LA; Buschelman, BJ; Rhomberg, PR; Sanford, MD; Hollis, RJ; Pfaller, MA; Herwaldt, LA. Outbreak of severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections caused by a contaminated drain in a whirlpool bathtub. Clin. Infect. Dis 2000, 31, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai-Komada, N; Hirano, M; Nagata, I; Ejima, Y; Nakamura, M; Koike, KA. Risk of transmission of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa through use of mobile bathing service. Environ. Health Prev. Med 2006, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, S; Sigge, A; Wiedeck, H; Trautmann, M. Analysis of transmission pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa between patients and tap water outlets. Crit. Care Med 2002, 30, 2222–2228. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel-Hill, E; Henry, DA; Speert, DP. Pseudomonas. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 9th ed; Murray, PR, Baron, EJ, Jorgensen, JH, Landry, ML, Pfaller, MA, Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 734–748. [Google Scholar]

- Dulabon, LM; LaSpina, M; Riddell, SW; Kiska, DL; Cynamon, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute prostatitis and urosepsis after sexual relations in a hot tub. J. Clin. Microbiol 2009, 47, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Muraca, P; Stout, JE; Yu, VL. Comparative assessment of chlorine, heat, ozone, and UV light for killing Legionella pneumophila within a model plumbing system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1987, 53, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Price, D; Ahearn, DG. Incidence and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in whirlpools. J. Clin. Microbiol 1988, 26, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, CF; Smith, PG. The survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during bromination in a model whirlpool spa. Lett. Appl. Microbiol 1992, 14, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aloush, V; Navon-Venezia, S; Seigman-Igra, Y; Cabili, S; Carmeli, Y. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gasink, LB; Fishman, NO; Weiner, MG; Nachamkin, I; Bilker, WB; Lautenbach, E. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: assessment of risk factors and clinical impact. Am J Med 2006, 119, 526e19–526e25. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environmental Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 18th ed; American Public Health Association: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Section 9213,; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reasoner, DJ; Geldreich, EE. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1985, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J; Lee, CS; Hugunin, KM; Maute, CJ; Dysko, RC. Bacteria in drinking water supply and their fate in gastrointestinal tracts of germ-free mice: a phylogenetic comparison study. Water Res 2010, 44, 5050–5058. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; eighteenth informational supplement (document M100-S18); The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- NSPF Pool and Spa Operator Handbook; National Swimming Pool Foundation: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2007.

- LeChevallier, MW; Cawthon, CD; Lee, RG; Lechevallier, MW; Cawthon, CD; Lee, RG. Factors promoting survival of bacteria in chlorinated water supplies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1988, 54, 649–654. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, AJ; Wenzel, RP. Epidemiology of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis 1984, 6, S627–S642. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases; Mandell, GL, Dolan, R, Bennett, JE, Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1820–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogues, AM; Boulestreau, H; Lashéras, A; Boyer, A; Gruson, D; Merle, C; Castaing, Y; Bébear, CM; Gachie, JP. Contribution of tap water to patient colonisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a medical intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect 2007, 67, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hoiby, N; Pers, C; Johansen, HK; Hansen, H. Excretion of beta-lactam antibiotics in sweat—A neglected mechanism for development of antibiotic resistance? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 2855–2857. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z; Weinberg, HS; Meyer, MT. Trace analysis of trimethoprim and sulfonamide, macrolide, quinolone, and tetracycline antibiotics in chlorinated drinking water using liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2007, 79, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, GE; Tobin, RS; Junkins, B; Kushner, DJ. Effect of chlorination on antibiotic resistance profiles of sewage-related bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1984, 48, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

| Location | Pool/Spa Size (m3) | Approximate Bather Load (per day) | Average Water Temperature (°C) | Average Free Chlorine (mg/L) | Average Total Chlorine (mg/L) | Turbidity (NTU) | P. aeruginosa-positive (%) Water (n) | P. aeruginosa-positive (%) Swab (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot tub–Residential | ∼1.80 | ∼1 | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | 100% (6/6) | 100% (4/4) |

| Hot tub–Public 1 | 8,593 | 60 | 39.1 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/5) |

| Hot tub–Public 2 | 14,237 | 50 | 38.9 | >10 | >10 | 0.2 | 0% (0/4) | 75% (6/8) |

| Swimming Pool 1 | 2,130,187 | 50 | 29.4 | 6.2 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 0% (0/4) | 25% (1/4) |

| Swimming Pool 2 | 3,758,770 | 220 | 26.2 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 0.1 | 0% (0/4) | 25% (1/4) |

| Swimming Pool 3 | 927,009 | 120 | 28.7 | 6.5 | >10 | 0.3 | 25% (1/4) | 0% (0/4) |

| Swimming Pool 4 | 590,997 | 110 | 27.4 | 7.8 | >10 | 0.4 | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/4) |

| Swimming Pool 5 | 24,383 | 65 | 29.4 | 6.9 | >10 | 0.2 | 0% (0/4) | 25% (1/4) |

| Swimming Pool 6 | Not Available | Not Available | 26.7 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 0.4 | 0% (0/8) | 0% (0/8) |

| Swimming Pool 7 | Not Available | Not Available | 28.6 | 9.8 | >10 | 0.1 | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/4) |

| Swimming Pool 8 | Not Available | Not Available | 32.4 | >10 | >10 | 0.1 | 0% (0/4) | 33% (3/9) |

| Additional antimicrobial agents tested | ||

|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial | Class | % Resistant |

| Ampicillin | Penicillin | 74 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | Beta-Lactam/B-Lactamase Inhibitor | 74 |

| Cefazolin | Cephem (cephalosporin) | 96 |

| Cefotetan | Cephem (cephalosporin) | 74 |

| Cefoxitin | Cephem (cephalosporin) | 78 |

| Cefpodoxime | Cephem (cephalosporin) | 30 |

| Cefuroxime | Cephem (cephalosporin) | 74 |

| Nitrofurantoin | Nitrofurantoin | 96 |

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Lutz, J.K.; Lee, J. Prevalence and Antimicrobial-Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pools and Hot Tubs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 554-564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020554

Lutz JK, Lee J. Prevalence and Antimicrobial-Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pools and Hot Tubs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011; 8(2):554-564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020554

Chicago/Turabian StyleLutz, Jonathan K., and Jiyoung Lee. 2011. "Prevalence and Antimicrobial-Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pools and Hot Tubs" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8, no. 2: 554-564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020554

APA StyleLutz, J. K., & Lee, J. (2011). Prevalence and Antimicrobial-Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Swimming Pools and Hot Tubs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(2), 554-564. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8020554