Abstract

The impact of four effective population-based interventions, focusing on individual behavioural change and aimed at reducing tobacco-attributable morbidity, was assessed by modeling with respect to effects on reducing prevalence rates of cigarette smoking, population-attributable fractions, reductions of disease-specific morbidity and its cost for Canada. Results revealed that an implementation of a combination of four tobacco policy interventions would result in a savings of 33,307 acute care hospital days, which translates to a cost savings of about $37 million per year in Canada. Assuming 40% coverage rate for all individually based interventions, the two most effective interventions, in terms of avoidable burden due to morbidity, would be nicotine replacement therapy and physicians’ advice, followed by individual behavioural counselling and increasing taxes by 10%. Although a sizable reduction in the number of hospital days and accumulated costs could be achieved, overall these interventions would reduce less than 3% of all tobacco-attributable costs in Canada.

1. Introduction

Smoking is one of the most important risk factors for the burden of disease. Tobacco use is responsible for high levels of morbidity and mortality. Smoking causes a substantially increased risk of mortality from lung cancer, upper aerodigestive cancer, several other cancers, heart disease, stroke, chronic respiratory disease and a range of other medical causes [1]. In the developed world in the year 2000, smoking was reported to be the risk factor with the largest attributable mortality and attributable disability adjusted life years (DALYS); specifically, 12.2% of all DALYS were attributed to this risk factor [2].

The second Canadian Cost Study indicated that the social costs for substance abuse in Canada are high, with a cost of $39.8 billion in 2002 [3,4]. The economic costs of tobacco abuse were the highest among all substances, with a cost of $17.0 billion, which represented 42.7% of the total substance abuse costs in Canada.

Given the evident overload of tobacco-attributable social burden, tobacco control measures have gained more importance. The use of cost-effective tobacco control measures is the key to further reduce the burden of tobacco smoking [5,6]; for the field of substance abuse see [7–9]. Analysis of avoidable burden and avoidable costs of tobacco-attributable morbidity in Canada was thus necessary in finding such effective measures.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of Interventions

The intervention selection was undertaken in two steps:

1) A collection of evidence for the most common interventions via a search of meta-analyses with a special emphasis on Cochrane Reviews; and 2) an expert consultation to select the best fitting types of interventions for Canada.

2.2. Methodological Considerations for Statistical Modeling

Based on previous publications [10–12], we decided to model the impact of different interventions in terms of burden of disease. This procedure can be justified by the fact that for tobacco abuse (The term “abuse” here is used in the economical definition and does not necessarily effect the psychiatric definition of DSM-IV)–contrary to alcohol abuse and illicit drugs–the overwhelming majority of direct costs materializes in health care [3,13,14].

The usual epidemiological model, as defined by burden of disease studies, especially on the international level [2,15–17], operates with one-dimensional risk factors and foresees the following steps:

- → Estimation of population disease with sex and age specific population-attributable fractions, in the case of tobacco with smoking-attributable fractions (SAF).

- → Based on SAF, tobacco-attributable morbidity expressed in the number of acute care hospital days.

2.3. Computing Smoking-Attributable Fractions

The contribution of a risk factor to disease or mortality, relative to some alternative exposure scenario (i.e., PAF, defined as the proportional reduction in population disease or mortality that would occur if exposure to the risk factor were reduced to an alternative exposure scenario, ceteris paribus [18,19]), is given by the generalized “potential impact fraction” in Equation 1, or its discrete version when the exposure variable is categorical [19–21]:

| RR(x) | relative risk at exposure level x |

| P(x) | population distribution of exposure |

| P′(x) | counterfactual distribution of exposure (often 0 = no exposure for tobacco) |

| m | maximum exposure level |

Since most diseases are multifactorial (caused by a multiple number of risk factors), and because some risk factors act through other more proximal factors, population-attributable fractions for multiple risk factors for the same disease can add up to more than 100% [22,23]. For example, some of the cardiovascular disease events may be due to a combination of smoking, physical inactivity and an inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables (all acting partially through obesity, cholesterol, and blood pressure). Such cases would be attributed to all of these risk factors. While the lack of additivity may seem problematic initially, multiple-causality offers the opportunity to tailor prevention based on the availability and the cost of the interventions. In terms of tobacco interventions, this means that the projected morbidity gains will be achieved through constellations, in which some of the gains could also be achieved by other interventions; e.g. the morbidity reduction of tobacco taxation on CHD could in part be achieved by improving physical fitness in the population. To estimate tobacco-attributable morbidity, SAFs were calculated using the discrete version of Equation 1.

2.4. Smoking Risk Relations

As indicated by Equation 1, the calculation of tobacco-attributable morbidity was based on the combination of relative risks (RRs) and prevalence of exposure. The selection of tobacco-related diseases and causes of morbidity relied on the comprehensive reviews by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [24] and the U.S. Government [1]. These reviews consider the following criteria in judgments of causality: consistency, strength of association, specificity, temporality, coherence, dose-response, and experimental evidence. Once identified, the conditions were translated into corresponding International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and 10 codes. The list of these conditions is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tobacco-attributable conditions included in this study and relative risks from English et al. [25].

The RRs were abstracted from a comprehensive review of the determinants of health prepared by the Australian Government, which contained systematic meta-analyses of the health effects of tobacco smoking [25]. The RRs for ex-smokers and current smokers are listed in Table 1. The SAFs for morbidity were calculated by combining the RRs with the exposure prevalence.

2.5. Prevalence of Smoking in Canada

Smoking prevalence for different levels of smoking consumption for Canada, as a whole, were obtained from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2003 (CCHS cycle 2.1), a population based representative survey conducted by Statistics Canada [26]. All prevalence estimates were sex- and age group-specific. However, the categorization of smoking status varied by specified disease and were based on the RRs available in the meta-analyses. For each disease, for which the identified meta-analysis included dose-response-specific RR, prevalence estimates were also dose-specific (e.g., never, former, current, 1–14, 15–24, 25+ cigarettes per day). Current smokers, those who reported occasional smoking or daily smoking, were further categorized by the number of cigarettes smoked per day, when sufficient information existed to do so.

In order to model smoking behaviour in Canada with pressure towards reducing smoking rates, we assumed a scenario based on the literature; e.g. trends observed in regions of North America and Australia featuring intense efforts to reduce tobacco related harm. These scenarios were based on the following (see also [27]):

- Yearly quitting rates of 10%;

- The assumption that 80% of smokers wanted to quit;

- The assumption of an annual incidence rate (new cases of smokers before and after intervention in the specified year) of 0.46% for current female non-smokers, and prevalence proportionate incidence rate for males.

2.6. Morbidity Data

The number of acute care hospital days in Canada for 2002 was obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), on the national and the provincial level according to ICD-10 codes. The national level data was composed of only seven provinces and two territories (Alberta, British Columbia, Newfoundland, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Yukon Territory). For the national level, data was provided for each disease condition, as well as for each sex and age 20+. Based on these figures, the data for Canada, as a whole, were estimated using the total population: the disease-specific rate of occurrence observed in the data provided was applied to the total population of Canada to obtain the estimated number of disease-specific occurrences.

The Hospital Morbidity Database (HMDB), held by CIHI, captures information on patients separated through discharge or death from acute care facilities in Canada. This database provides national data on acute care hospitalizations by diagnoses and procedures excluding day procedures (e.g., day surgeries), outpatient, and emergency department visits. The HMDB also includes data on newborns but not stillborns and cadaveric donor “discharges”. Also to note, figures are based on facility geography, that is, where the hospital is located, thus possible non-Canadians may be included. Additionally, the statistics reflect the number of hospitalizations, which is somewhat higher than the number of individuals diagnosed since individuals with multiple admissions during a single year would be counted more than once.

The number of hospital days (i.e., length of stay) is associated with the condition coded as Most Responsible Diagnosis (MRD) on the patient’s hospital record. This means that the MRD accounts for the most of the days a patient stays in a hospital. A diagnosis of MRD is described as the most significant condition of the patients’ that is responsible for his/her stay in the hospital. When multiple diagnoses are classified as the most responsible, coders are instructed to code the diagnosis responsible for the longest length of stay [28]. As the hospital days based on the MRD may overlap in cases with more than one MRD, the calculated hospital days had to be adjusted to the overall hospital days in Canada. This adjustment implied a province-specific application of a shrinkage factor, derived by dividing the number of hospital days in a province by the number of MRD hospital days in the same province.

2.7. Estimating Avoidable Morbidity and Its Cost

The baseline scenario costs of acute care hospitalizations were estimated by multiplying the SAF for conditions known to be affected or caused by tobacco smoking by the aggregate number of acute care hospital days for each condition by age and sex. These figures were then multiplied by the per diem cost of acute care hospital days, by condition and by province or territory, using costs obtained from a variety of sources (Table 2, [3,29]). The total national figures were then calculated by aggregating the total costs due to tobacco-attributable conditions across provinces and territories.

Table 2.

Total cost per night in acute care hospital per province and territory, and Canada, 2002.

To compute the avoidable costs of the interventions related to acute care hospital days, we applied the estimated percentage changes in the SAF caused by the intervention for each tobacco-attributable condition to the baseline figures. We, thereby, obtained the changes in costs for all tobacco-attributable conditions, which were then aggregated to provide the estimated avoidable cost of each intervention.

3. Results

3.1. Collection of Evidence for Most Common Interventions

Fifty-one systematic reviews were found with respect to the effectiveness of specific smoking-related interventions. Seven experts were contacted to identify four evidence-based intervention strategies to reduce tobacco-attributable morbidity in Canada. As a result, the following interventions were selected based on the feedback of the experts:

a) Public policy interventions:

1) Price increase

There is a strong link between the price of cigarettes and its consumption: increases in the cost of cigarettes to the consumer will decrease consumption rates and, therefore, decrease tobacco-related problem rates.

b) Interventions focusing on individual behavioural change (counselling, brief advice, therapy):

2) Individual behavioural counselling (IBC) for smoking cessation

IBC was defined as a face-to-face encounter between a smoking patient and a counsellor trained in assisting smoking cessation. This excludes counselling delivered by doctors and nurses as part of clinical care.

3) Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smoking cessation

NRT included chewing gum, transdermal patches, nasal spray, inhalers (a cigarette-like device which delivers nicotine to the buccal mucosa by sucking) and tablets or lozenges.

4) Physician advice for smoking cessation

Physician advice to stop smoking was defined as verbal instructions from the physician with a ‘stop smoking’ message irrespective of whether or not information was provided about the harmful effects of smoking. Advise as part of multifactorial lifestyle counselling (e.g., including dietary and exercise advice) was excluded. Therapists were physicians, or physicians supported by another healthcare worker.

Table 3 provides a summary of the effectiveness of the selected interventions.

Table 3.

Interventions and their effectiveness.

3.2. Exposure

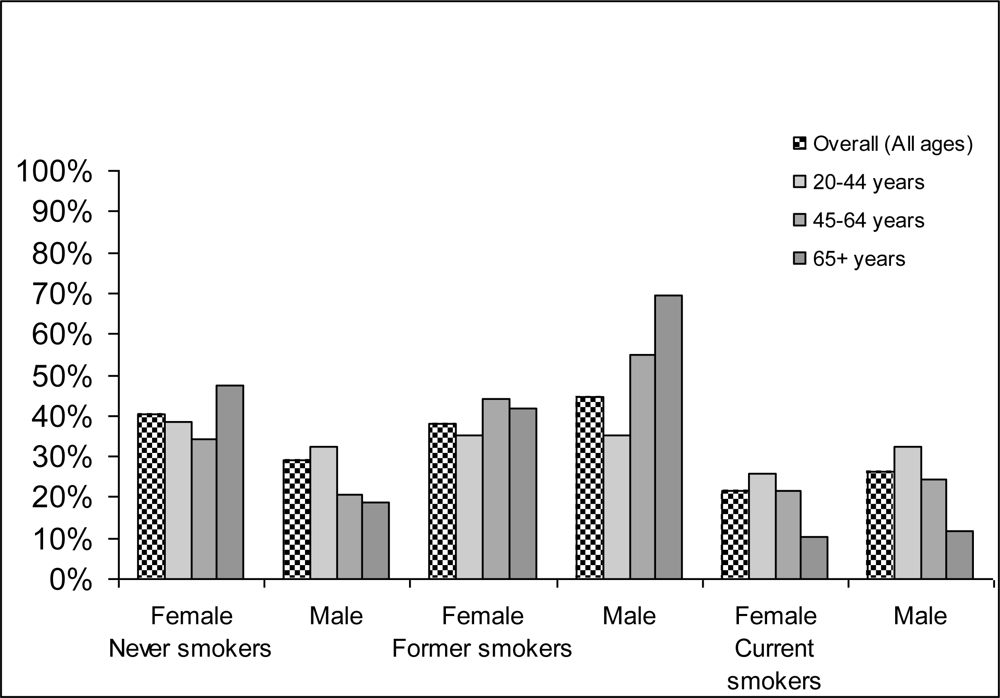

Figure 1 provides an overview of exposure to smoking in Canada by sex and age. As expected, men smoked more than women on average, and smoking prevalence decreased with age.

Figure 1.

Prevalence in percentage of different smoking categories by gender and age in Canada in 2002.Source: Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2003 [26]

3.3. Tobacco-Attributable Morbidity in Canada 2002

Overall, 1,408,252 hospital days were estimated to be attributable to tobacco (815,059 for men and 593,193 for women) in Canadian population over 20 years old in 2002. This constitutes 6.6% of all hospital days in acute care hospitals in Canada (men: 8.5%; women: 5.0%).

The two single disease categories ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and lung cancer made up the majority of tobacco-attributable acute care hospital days - about 40% (35.9% in men, 45.3% in women). Specifically, IHD accounted for 25% of the total tobacco-attributable hospital days (350,793 hospital days; men: 173,418; women: 177,375). The next largest single category was lung cancer (15%; 209,627 hospital days, men: 118,788, women: 90,839).

3.4. Effectiveness of Interventions

Table 4 translates the effects of selected interventions into the common metric of smoking prevalence rates in the Canadian adult population (operationalized as all inhabitants 15 years and older).

Table 4.

Detailed results of effectiveness of different interventions for smoking cessation on prevalence of smoking in Canada (2002).

3.5. Avoidable Morbidity and Its Cost in Canada

Table 5 shows the effectiveness of interventions on morbidity, measured as acute care hospital days, in Canada. The results revealed that an implementation of the four aforementioned interventions related to tobacco policy combined would result in a savings of 33,307 acute care hospital days.

Table 5.

Interventions and their impact on tobacco-attributable acute hospital days (all cause), 20+ years in Canada (2002).

This would result in cost savings of about $37 million in Canada per year (Table 6).

Table 6.

Net savings of tobacco-attributable cost (CND $) due to implementation of selected interventions in Canada (2002).

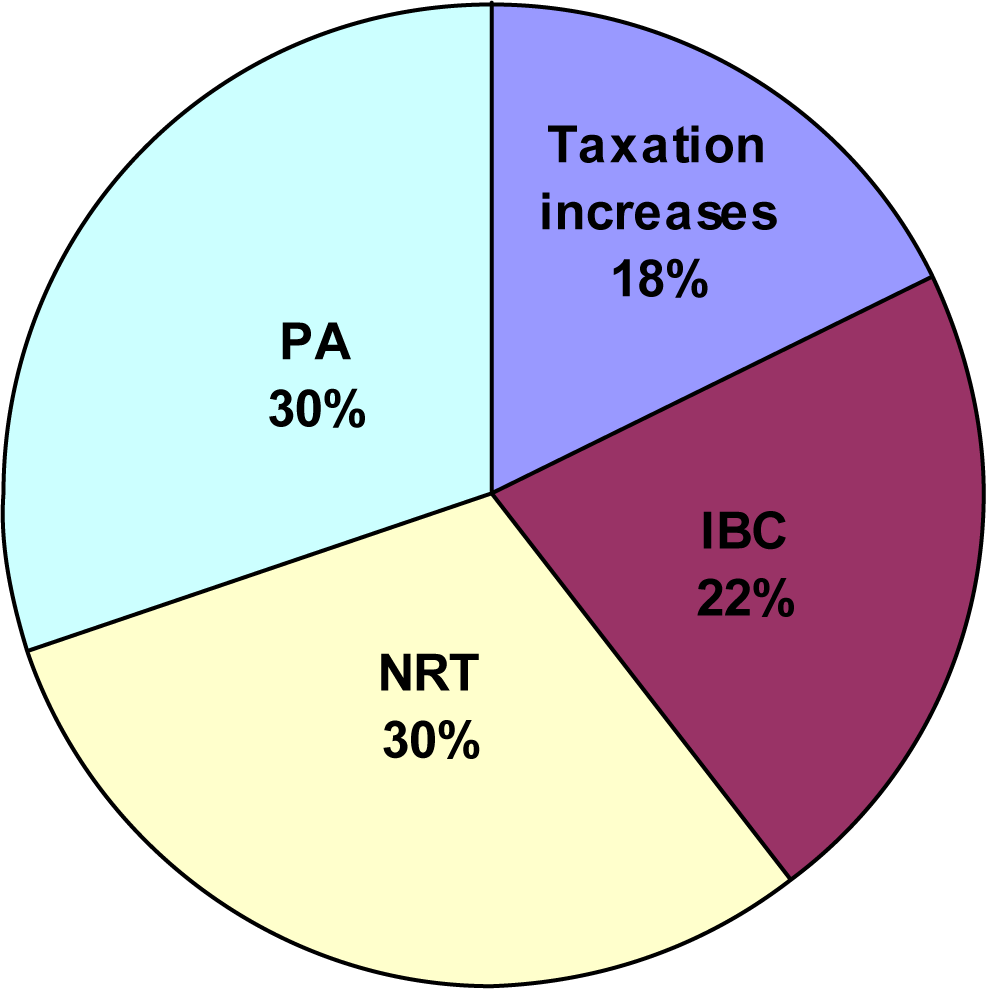

The most effective intervention in terms of avoidable burden due to morbidity was nicotine replacement therapy and physician’s advice (savings more than $11 million per each intervention, 60% of total savings), followed by individual behavioural counselling (more than $8 million per year, 22% of total savings) and increasing taxes (more than $6.5 million per year, 18% of total savings; Tables 5, 6 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interventions and their impact on tobacco-attributable acute hospital days (all cause), 20+ years in Canada (2002).IBC–Individual behavioural counsellingNRT–Nicotine replacement therapyPA–Physician’s advice

Additionally, this study estimated the effect of the interventions on the burden and the cost of two of the biggest contributors: IHD and lung cancer. The results revealed that an implementation of the four interventions related to tobacco policy combined would result in a savings of 20,264 acute care hospital days due to IHD and 1,052 acute care hospital days due to lung cancer in Canada. This would result in cost savings of about $22.5 million (57% of total savings) for IHD and more than $1.2 million for lung cancer in Canada per year.

3.6. Limitations and Conclusion of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, the effects of all interventions were modeled as if they occurred instantaneously, therefore the combined effect of four interventions is possibly overestimated. In addition, the study did not estimate over what periods of time that these benefits in morbidity and cost would be achievable. Furthermore, the choice of implementing a single intervention or combined interventions serves as lower and upper estimates, respectively, for this study.

The study also overestimates the effects on chronic health conditions that are solely attributable to tobacco. For example, if some intervention could reduce tobacco consumption to zero at a certain point in time, tobacco-related disease burden would not be zero immediately thereafter. Instead, some burden of disease would persist due to previous tobacco consumption. For instance, there will be some people already having tobacco-attributable lung cancer and some people may even develop new lung cancer or other cancer in the future based on their past tobacco exposure.

The study also did not take into consideration the effects of the ongoing interventions aimed to prevent multifactorial diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

In addition, current estimates of avoidable acute care hospital days due to tobacco use and its cost do not reflect the rates of return that the society might achieve. In order to compute the potential rates of return on expenditure, it is necessarily to conduct a cost benefit analysis.

In this study only four exemplary interventions were modeled as a demonstration of the possibility of improving population health and saving public health expenditures associated with tobacco smoking. There are many more effective population-based intervention and interventions focusing on individual behavioural change which would further reduce tobacco-attributable burden and its associated costs. It is our hopes that this study can positively influence the decision making on tobacco control in Canada.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the “Small Project Grants for Canadian Researches” awarded to S. Popova from the Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. In addition, this contribution was, in part, enabled by funding from various sources allocated to the Second Canadian Study on Social Costs of Substance Abuse, under the umbrella of the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

In addition, support to CAMH for salary of scientists and infrastructure has been provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

References

- USDHHS – US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General; USDHHS, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J; Baliunas, D; Brochu, S; Fischer, B; Gnam, W; Patra, J; Popova, S; Sarnocinska-Hart, A; Taylor, B. The Costs of Substance Abuse in Canada 2002; Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J; Gnam, W; Popova, S; Baliunas, D; Brochu, S; Fischer, B; Patra, J; Sarnocinska-Hart, A; Taylor, B. The social costs of alcohol, illegal drugs and tobacco in Canada 2002. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2007, 68, 886–895. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, M; O’Brien, B; Stoddart, GL; Torrance, GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, M; McGuire, A. Economic Evaluation in Health Care: Merging Theory with Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J. Ökonomische Aspekte von Substanzmissbrauch. In Lehrbuch der Suchterkrankungen; Gastpar, M, Mann, K, Rommelspacher, H, Eds.; G Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999; pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J; Frick, U; Fischer, B. Zur Ökonomie des Suchtmittelgebrauchs. In Oekonomie der Sucht und Suchttherapie; Tretter, F, Erbas, B, Sonntag, G, Eds.; Pabst: Lengerich, Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tretter, F; Erbas, B; Sonntag, G. Okonomie der Sucht und Suchtterapie; Pabst: Lengerich, Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati, M; Lopez, AD; Rodgers, AD; Vander Hoorn, S; Murray, CJL; Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of Ddisease. Lancet 2002, 360, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati, M; Vander Hoorn, S; Rodgers, A; Lopez, A; Mathers, C. Estimates of global and regional potential health gains from reducing multiple major risk factors. Lancet 2003, 362, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya, K; Ciecierski, C; Guindon, E; Bettcher, D; Evans, D; Murray, C. WHO framework convention on tobacco control: development of an evidence based global public health treaty. BMJ 2003, 327, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Single, E; Robson, L; Xie, X; Rehm, J. The costs of substance abuse in Canada; Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Single, E; Robson, L; Xie, X; Rehm, J. The economic costs of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs in Canada, 1992. Addiction 1998, 93, 991–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C; Lopez, A. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C; Evans, D; Archarya, A; Blatussen, R. Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ 2000, 9, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, O. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am. J. Epidemiol 1974, 99, 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, G; Heuch, I. Attributable fractions: fundamental concepts and their visualization. Stat. Methods Med. Res 2001, 10, 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, SD. The estimation and interpretation of attributable risk in health research. Biometrics 1976, 32, 829–849. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, SD. Prevention of multifactorial disease. Am. J. Epidemiol 1980, 112, 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K. Causes. Am. J. Epidemiol 1976, 104, 587–592. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K; Greenland, S. Causation and Casual Inference, 2nd ed; Lippincott-Raven Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- IARC – International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking; IARC: Lyon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- English, D; Holman, C; Milne, E; Winter, M; Hulse, G; Codde, G; Bower, G; Corti, B; de Klerk, N; Knuiman, M; Kurinczuk, J; Lewin, G; Ryan, G. The quantification of drug caused morbidity and mortality in Australia 1995; Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health: Canberra, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, cycle 2.1; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, Cannada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J; Zahringer, S; Egli, S. The Epidemiologic and Economic Evaluation of Different Forms of Tobacco Prevention for Switzerland: an Analysis of Exemplary Interventions using Secondary Data; Insitut fur Suchtforschung (ISF): Zurich, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- CIHI-Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data Quality Documentation: Discharge Abstract Database 2002–2003; CIHI: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- CIHI-Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian MIS Database: Hospital Finance Performance Indicators 1999–2000 to 2001–2002; CIHI: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ranson, K; Jha, P; Chaloupka, F; Nguyen, S. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco-control policies. In Tobacco Control in Developing Countries; Jha, P, Chaloupka, F, Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, T; Stead, LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Silagy, C; Lancaster, T; Stead, L; Mant, D; Fowler, G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, T; Stead, L. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004, 4. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).