Introduction

The World Health Report 2006 [

3], a clarion call for action, is dedicated entirely to the human resources for health crisis amidst growing concerns that the global targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) may not be attainable in the face of this crisis. This paper describes the extent of the global health workforce crisis and focuses on the reasons for, and the effects of the crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. A description is then made of the tested and tried strategies and documented best practices used in addressing the crisis, and these include country-led and country-specific actions. Global responsibility and collective solidarity, including solutions beyond the health sector, are needed if the health workforce crisis is to be successfully tackled for positive impact on health outcomes in the overall context of human development.

Findings

The global face of the human resources for health (HRH) crisis

There is growing recognition globally that the health workforce shortage has reached epic proportions. The shortages affect nearly all countries across the globe. The World Health Organization estimates that a total of 4¼ million health workers are needed to fill the gap [

1].

The Global health workforce by density

Amidst the shortages, the serious issue of global mal-distribution of health workers reflects inequities that are even more marked than inequities in health status. To achieve the MDGs, the minimum level of health workforce density is estimated at 2.5 health workers per 1,000 people [

1]. Out of 46 countries in the sub-Saharan Africa region, only 6 have workforce density over 2.5 per 1,000 people. Indeed, Africa’s health workforce density averages 0.8 workers per 1000 population, significantly lower compared to the other regions and to the world median density of 5 per 1,000 population [

2].

Asia, with about 50 percent of the world’s population, has 30 percent of the global stock of doctors, nurses, and midwives. Together, Europe and North America have 20 percent of the world’s people, but have almost half of the physicians and 60 percent of the nurses. Africa has only an average of 2.3 health workers (all categories combined) per 1000 population, compared to 18.9 and 24.8 for Europe and the Americas respectively (

Table 1) [

3]. The availability of health workers has now become an indicator that differentiates the “haves” from the “have-nots”, the developed countries from the developing, and the rich nations from the poor ones, with the nations of Europe and North America having the highest densities of trained health workers.

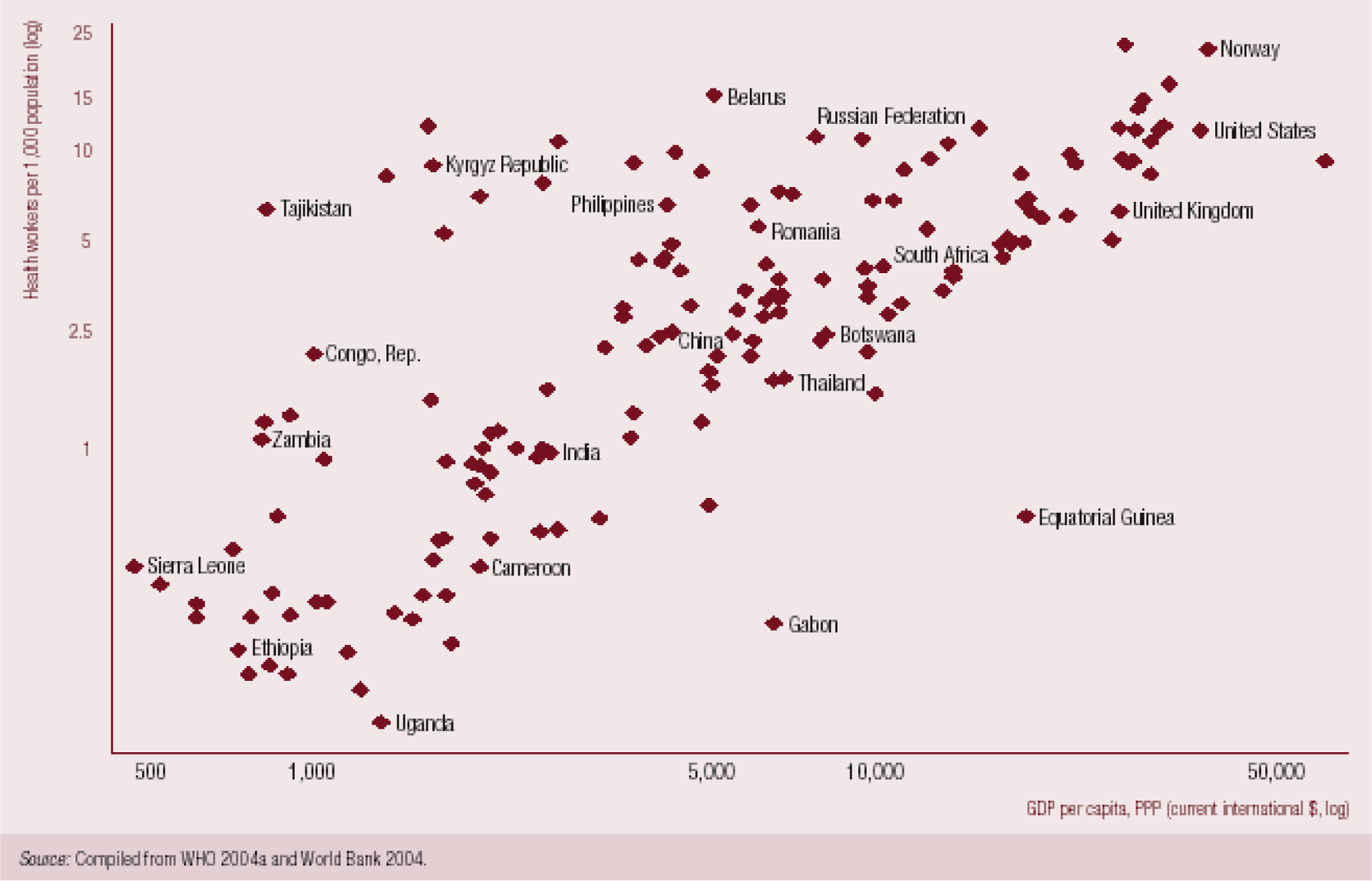

Human resources for health and national wealth

In general, countries with higher per capita GDP and incomes have more health workers (

Figure 1). Norway and the United States of America are among the countries with the highest per capita income and the greatest density of health workers per 1000 population. Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest per capita income as well as the lowest health worker density. However, some exceptions exist where countries with abundant material resources and high income (e.g. Gabon and Equatorial Guinea) still have relatively inadequate numbers of health workers. Inequities also exist within countries, with urban, wealthier areas having greater proportions of all trained health workers than rural and poorer areas of countries.

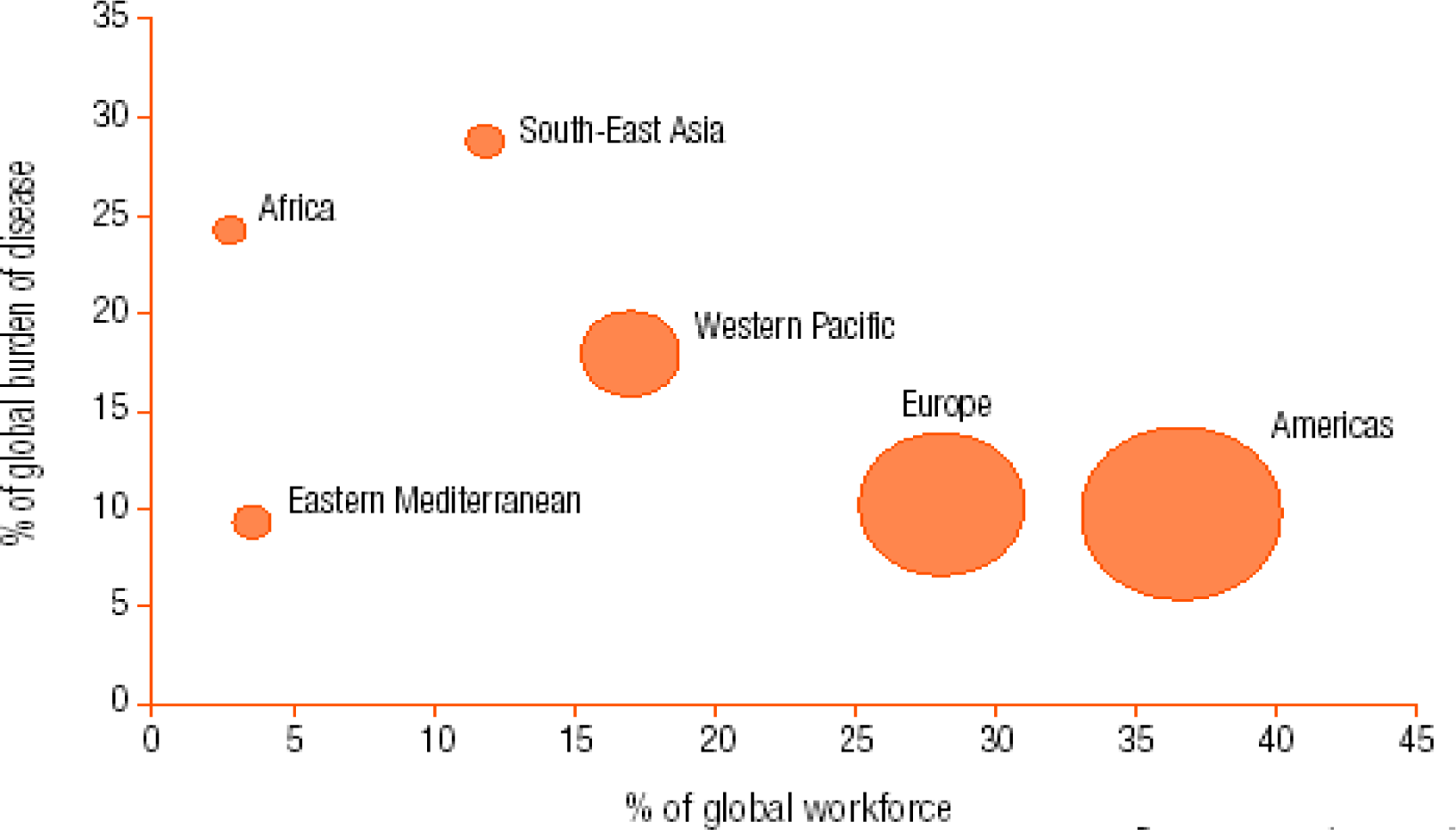

Distribution of health workers and burden of disease

Ideally, countries with the highest burden of disease should have the greatest numbers of skilled health workers. Unfortunately, this is not the case in today’s world. Between regions, sub-Saharan Africa faces the greatest challenges (

tables 2,

3 and

figures 2,

3). The region has about 11% of the world’s population, bears over 24% of the global disease burden, is home to only 3% of the global health workforce, and spends less than 1% of the world’s financial resources on health. On the other hand, the Americas (mainly USA and Canada) are home to 14% of the world’s population, bear only 10% of the world’s disease burden, but have 37% of the global health workforce and spend about 50% of the world’s financial resources for health. It is worthy of note that a good proportion of the health workforce in the Americas originates from sub-Saharan Africa. Details are presented later on in this paper.

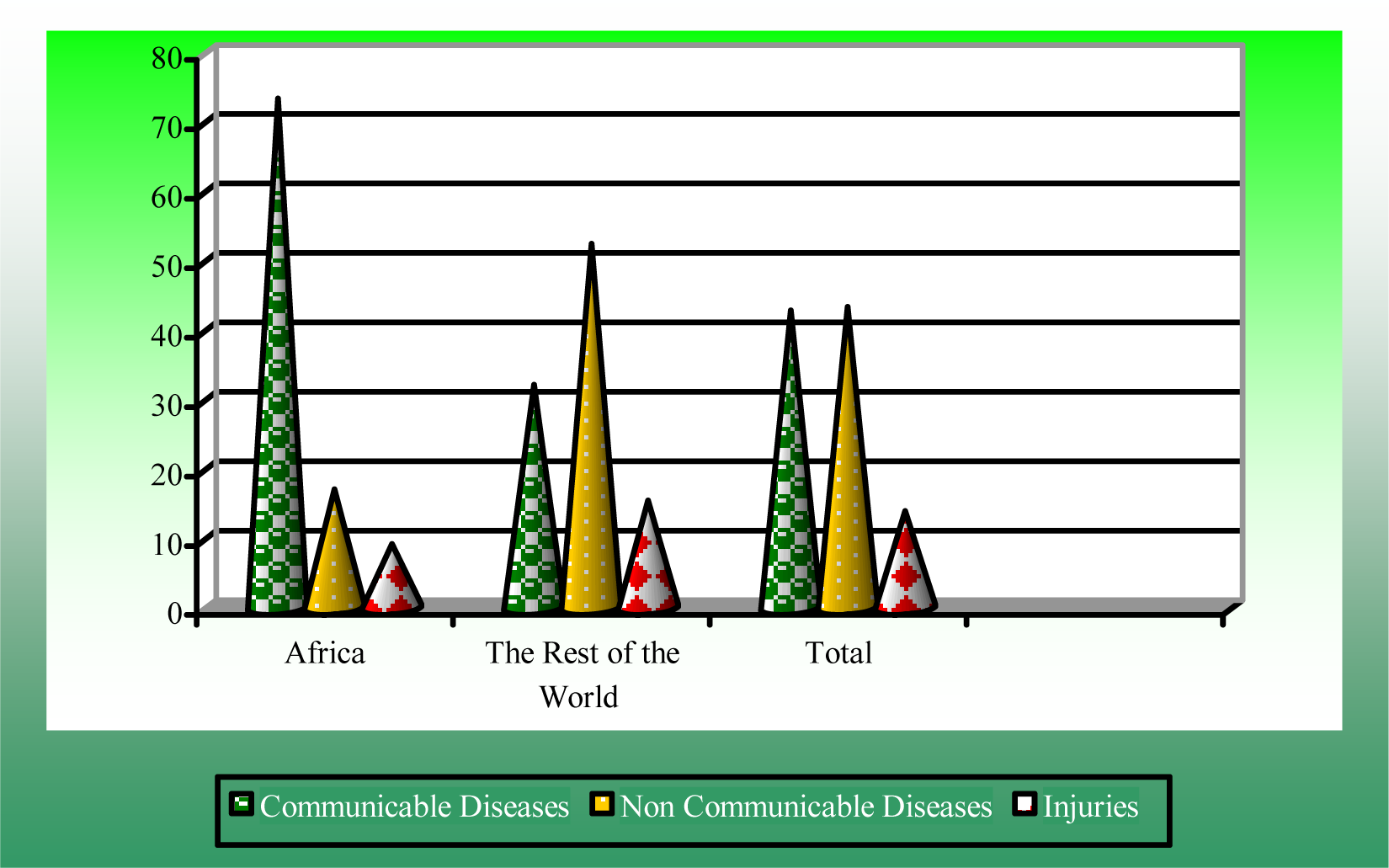

Table 2 summarizes the differences between the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa carries about 74% of the global burden of communicable diseases (

table 3,

fig. 2), among which are the three biggest causes of morbidity and mortality, namely malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS-related illnesses.

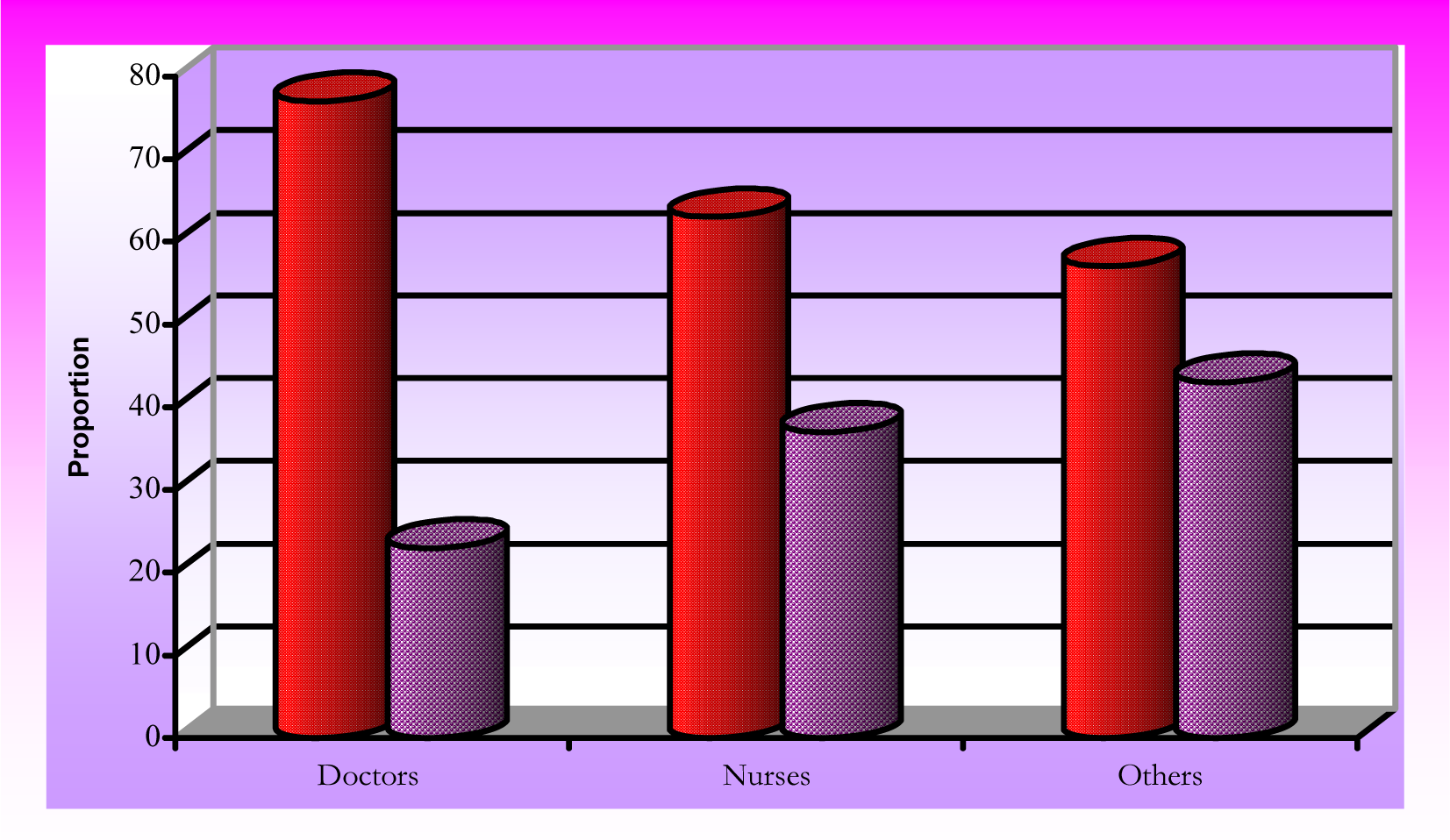

The urban-rural divide regarding HRH

In general, amidst the inter-country and inter-regional imbalances in the density of the health workforce, there are also intra-country inequities, with greater numbers and better trained health workers concentrated in urban areas, to the detriment of rural areas (

fig. 4).

Many factors influence the geographical distribution of health worker density world-wide. The most common factors that force health workers away from jobs in rural areas are the lack of incentives and amenities, as well as limited opportunities for career progression. With the very low salaries of health workers in sub-Saharan Africa, health workers in urban areas tend to compensate through unauthorized private practice, or resort to predatory behaviour such as extracting under-the-counter payments from patients, or misappropriating drugs or other supplies (4). In Tanzania, the capital city of Dar-es-Salaam alone has nearly 30 times as many medical officers and medical specialists as any of the rural districts [

5].

The extent of the HRH crisis in sub-Saharan Africa

The global problem of inadequate human resources for health is most acute in sub-Saharan Africa where the scope of the health workforce crisis is alarming. There is simply insufficient adequately trained human capacity, of all cadres, in the region to absorb, apply and make efficient use of the interventions being offered by many new health initiatives. Among the key problems contributing to the shortages are the insufficient training opportunities. Africa is woefully lacking in facilities to train health workers. Two-thirds of sub-Saharan African countries have only one medical school, and 11 sub-Saharan countries have no medical school at all. In general, the health personnel to population ratios in sub-Saharan African countries have been higher than those of the rest of the world (5). In the 1980s, one doctor catered for 10,800 persons in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 1 for 1,400 in all developing countries combined, and 1 for 300 in industrialized countries. In the same period, one nurse catered for 2,100 persons in Africa, compared to 1 for 1,700 persons in all developing countries combined, and 1 for 170 in industrialized countries [

6]. In Mozambique in 2006, 3 physicians and 21 nurses cater for 100,000 inhabitants, a workforce density most certainly incompatible with the possibility of achieving or sustaining 80% of essential health priority program me goals [

6].

In selected sub-Saharan African countries, between 20% and 60% of all physicians trained in these countries now work abroad (

table 4). The migration of skilled health workers, infamously known as the “brain drain”, is one of the most prevalent causes of the health workforce crisis in the region.

Forces influencing the HRH Crisis in sub-Saharan Africa

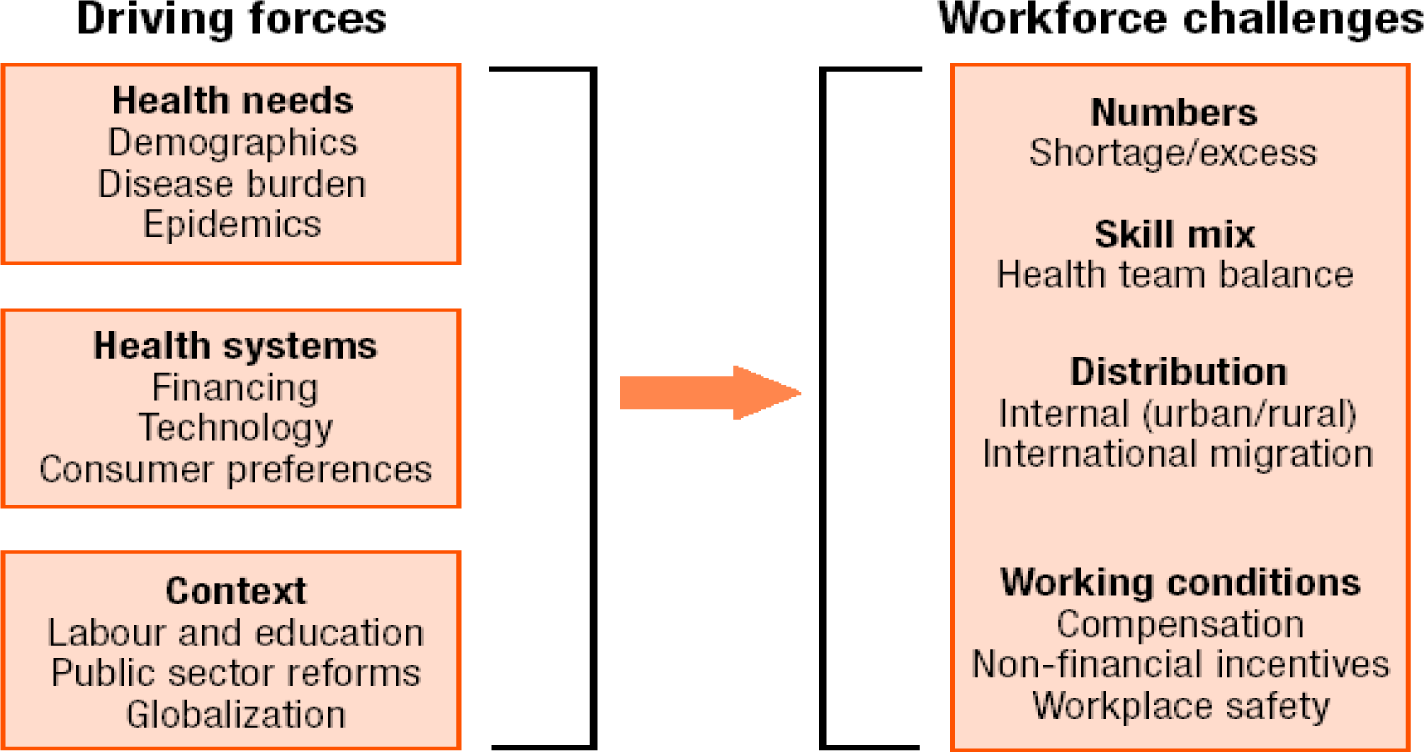

There are numerous forces (“push” and “pull” factors) that influence the health workforce crisis in sub-Sahara. These range from “driving forces” to “workforce challenges” (

figure 5) seeking to describe and to explain the extent and the rationale of the crisis.

Health needs

The high burden of disease and epidemics, especially the HIV/AIDS pandemic, has put a terrible strain on the health workforce, given that the production of health workers has not kept pace with the need. Besides, the HIV/AIDS pandemic has also taken its dreadful toll on the health workforce itself. With the increasing deaths from AIDS, the numbers of those who are supposed to help fight the disease are dwindling. In many sub-Saharan African countries, between 18% and 41% of the workforce is already infected with HIV [

5]. Burnout of remaining practicing health workers is cause and consequence of the HRH crisis.

Health systems

Poor economic growth and successive fiscal difficulties appear to be the immediate causes of the crisis. On the one hand, budgetary stringency under health sector reforms that accompany structural adjustment programmes has reduced African governments’ ability to attract, employ and retain well-trained health workers. Likewise, inadequate investment in the health sector, with unmet needs in the training of all cadres of health workers, and in the refurbishment of health care facilities, has resulted in inadequate numbers and skills of health workers, and in the migration of health workers.

Global context

The low birth rate in developed countries, with the resulting low numbers of persons training to be health workers, as well as the increasingly large populations of the elderly that require high levels of care, pull large numbers of health workers from the developing to the developed countries.

Diverse workforce challenges

The shortages of health workers in the public sector while there are large numbers of unemployed, trained and skilled health workers in-country (health and/or public sector reforms).

Presence of health workers with skills not suited for the health needs of their countries or communities (skill mix). For both doctors and nurses, African countries have largely focused on clinical training and specialties, rather than on the more relevant public health training. Example of doctors in the Philippines retraining themselves as nurses to pursue lucrative opportunities in changing export markets.

Internal mal-distribution (unequal and inequitable distribution) of health workers, with most located in urban areas, and moving from the public to private sector.

International migration of skilled health workforce (brain drain) from the developing to developed countries.

Dismal working conditions for health workers, including unsafe workplaces, inadequate compensation and incentives (financial and otherwise), and insufficient or no career development opportunities.

Overall, the combined effects of accelerated retrenchment, voluntary retirement and departure, internal and external migration for all reasons, and sickness and death from communicable and noncommunicable diseases, place sub-Saharan Africa at the epicentre of the global health workforce crisis.

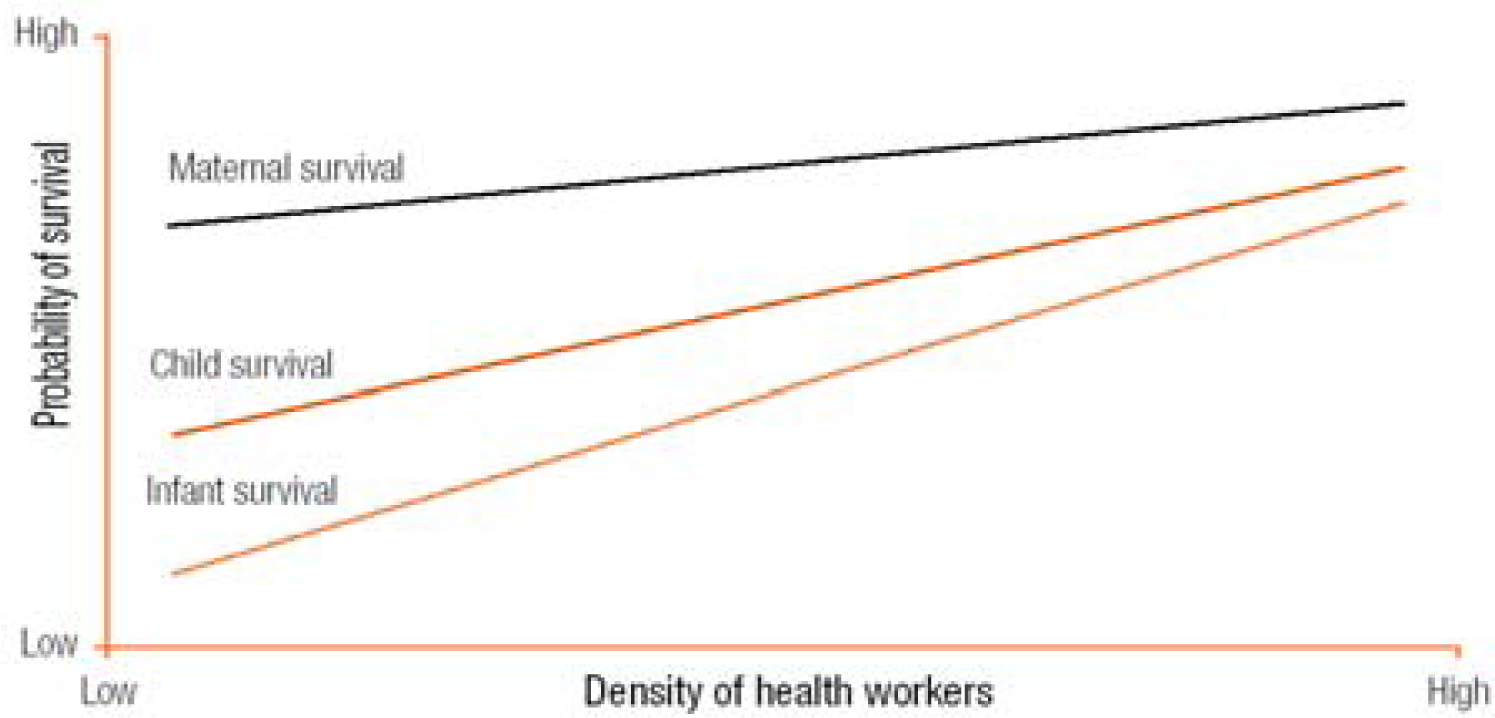

Effects of the HRH crisis

The global shortage of human resources for health is a crisis of epic proportions, posing an ominous threat to health development in the overall context of human development. Health care delivery is a labour-intensive service industry. Health service providers are the backbone of a health system’s core values: they treat and care for people, ease pain and suffering, prevent disease and mitigate risk, and are the link connecting knowledge to health action. There is ample evidence that health worker numbers and quality health care are positively correlated, especially in the domains of immunization coverage, primary care, and infant, child and maternal survival (

figure 6). Pressing health needs across the globe cannot be met without adequate numbers of well-trained and available health workers.

The attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), a blueprint agreed upon by countries and leading development institutions for meeting the needs of the world’s poorest people, faces major impediments on account of the health workforce crisis. The goals to reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, combat HIV/AIDS and other diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria, and to ensure access to essential medicines will not be met in sub-Saharan Africa if there is no drastic and immediate improvement in the availability and quality of essential health workers. Emerging global threats such as outbreaks of avian influenza will overwhelm local and national health systems and will undoubtedly not be contained by the present global levels of health workers.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic is a uniquely vicious peril to the health workforce. HIV/AIDS is responsible for a lot of the attrition of the health workforce through HIV-related mortality. A Kenyan study cites hospital-bed occupancy rates that have reached 190% due to HIV/AIDS [

8]. Increased need for testing and follow-up of suspected HIV-infected patients has also been noted as an additional burden on already over-stretched staff, thus increasing overall workload requirements.

In the HIV/AIDS literature, scaling up treatment with antiretroviral drugs was estimated to require between 20% and 50% of the entire available health workforce in four African countries, but less than 10% of health workers in the other 10 countries surveyed [

9]. In addition to that, the opportunity costs for treating HIV have proven immense in the presence of the health workforce crisis. A recent review in Zambia showed that as Anti Retroviral Therapy (ART) is scaled up, there is a decline in routine immunization coverage. The limited number of available health workers cannot adequately manage to carry out both tasks effectively [

10].

The critical shortages in human resources for health constitute one of the key causes of exclusion to access to quality health care, and this is especially true in rural Africa. The WHR 2006 while acknowledging that many more mothers and children currently have access to reproductive, maternal and child care entitlements than ever before in history, also observes that in many countries, however, universal access to the goods, services and opportunities that improve or preserve health is still a distant goal. The report observes that in too many countries a varying but large proportion of the populations remains excluded from the health benefits that others in the same country enjoy. This is particularly true for most sub-Saharan countries where the health worker crisis results in the exclusion of the rural poor to quality health care. In the 42 countries that in 2000 contributed 90% of all deaths of children under five years of age, 60% of children with pneumonia failed to get the antibiotic they needed, and 70% of children with malaria failed to receive treatment [

11]. The lack of trained health workers in most instances contributed heavily to the failure to receive treatment.

Tackling the HRH Crisis

The High Level Forum on MDGs held in Abuja in December 2004 acknowledged that unless action is taken urgently to address the human resource for health crisis, many countries will fail to reach their Millennium Development Goals and this would not merely represent a missed deadline but a real calamity for the impoverished citizens of the affected countries (

5).

The three dimensions to the crisis in human resources for health namely, the overall shortage, the mal-distribution and the low productivity of health workers need to be addressed to tackle the crisis. Although no one solution is available or feasible, the overall goal of any remedial action will be to get the right health workers with the right skills in the right place and doing the right things. Each country is unique but each can and should learn from the experiences of others. Best practices abound and need to be shared. Some of the plausible solutions for tackling the health workforce crisis are outside the health sector and countries need to employ multi-faceted approaches to achieve the highest gains. Some of the most promising approaches are described below and they all target the training, retention and sustenance of skilled health workers.

Increase investment in pre-service training (intake and output)

The number of trained health workers in sun-Saharan Africa has historically been inadequate, with severe scarcities of almost all cadres due to economic and fiscal difficulties. The most obvious response to a shortage of human resources is to train more. An effective approach for quick short-term gains would be to train large numbers of health workers with basic clinical skills (enrolled nurses, midwives, clinical officers) and community health workers, especially trained to meet the health needs of their localities. Providing scholarships for poor students, for those from remote rural areas, and for high academic achievers is one way of attracting students to and keeping students in the health professions.

In some cases it may be helpful to relax entry requirements into health institutions. This can be done in conjunction with the introduction of catch-up courses to fill in gaps left by poor secondary school education. In Malawi this approach has made it possible to expand the medical school yearly intake from 20 to 60 [

5].

Efforts to expand pre-service training should go hand in hand with the availability of trainers or else the efforts may falter if trainers are not readily available, as was the experience in Ghana [

14]. Pre-service training for health workers should take into consideration measures to attract and retain tutors and trainers.

For training of sufficient numbers of health workers, the private sector needs to partner with the public sector and national governments need to provide incentives to private institutions to encourage them to train health workers.

Improve income and living wage

The single most crucial factor in the infamous ‘brain drain’ is the issue of salaries and conditions of service. All measures considered, improvement in health workers’ pay rates will not reduce health worker outflows. Failure to improve conditions of service will lead to coping mechanisms such as ‘private practice’ within public institutions. In some countries like Bangladesh and Egypt, the majority of all physicians in the public sector see private paying patients to supplement income from their regular jobs, while in Kazakhstan “informal payments” are estimated to add 30% to the national health care bill [

12]. Wage increases usually target the cadre with the highest net outflow rates. However, implementation of pay rises is fraught with numerous barriers and constraints, including public wage bill expenditure ceilings, and other fiscal constraints.

One effort to improve pay was Ghana’s Additional Duty Hours Allowance which is claimed to have had an immediate short term effect on retaining staff. However, there has not been a comprehensive evaluation and anecdotal evidence suggests that the long-term effect on health worker retention is negligible [

5]. In Tanzania the Selective Accelerated Salary Enhancement scheme has provided an opportunity for ministries to raise levels of remuneration for high priority groups but the long term effect is yet unknown [

13].

De-linking health workers from the civil service can be an alternative approach to improving their wages without involving the entire civil service. This was attempted in Zambia but the proposal encountered resistance from professional groups and eventually was not implemented. Ghana, on the other hand, has successfully de-linked tax collectors and bank employees from the civil service but not yet health workers [

14].

Providing better housing, reducing occupational risks of contracting HIV and other infections, lowering workloads, improving supervision, making it easier for health workers to remain in employment whilst accompanying their spouses on postings or bringing up a young family, are measures which countries can attempt to implement. It is very important though that the health workers are consulted and are on board all time.

Extend retirement ages

Retirement age in most sub-Saharan African countries is early compared to countries in Europe. In Zambia for instance, the retirement age for health workers is 55 years. Often, the retiring health workers are still in good health, are highly skilled and are able to perform their duties well with little supervision. This group is an untapped resource-pool that could make a difference. In Malawi, it is estimated that there are 800 to 1200 nurses currently not working in their field. In Ghana where the retirement age is 60 years, government has issued a call to reappoint retired health professional and up to two thirds of eligible doctors and nurses have applied. They are given two-year renewable contracts till the age of 65years [

5,

14]. Some countries have changed the retirement ages or planned to change these in order to extend the working life of their staff.

Recruit from abroad

Wealthier countries recruiting from less endowed ones is the root of the infamous “brain drain”, and is to be decried. However, recruitment can be done from countries that have an abundance of health workers. In sub-Saharan Africa, many governments have agreements with Cuba to recruit their doctors. Ghana, for example, employs over 200 Cuban doctors on two-year contracts and these doctors serve some of the most remote areas in the country [

5].

In the past, donor (developed) countries provided expatriate health workers to work in sub-Saharan countries, but the practice has been largely abandoned for reasons of cost and sustainability. In Zambia, the Dutch government has converted the funds which once served to pay expatriate Dutch doctors to work in Zambia, into the “Health Workers Rural Retention Scheme”. These funds are used for improving the overall pay package and conditions of service for Zambian doctors who work in the rural districts of the country. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this project is a great success with Zambian doctors now getting deployed to even the most rural districts where previously no Zambian doctor was willing to serve.

Achieve a more appropriate mix of skills

To alleviate the health worker crisis in sub-Saharan Africa, there is need to remove some of the hitherto unrealistic standards and barriers to professional practice that exist. Clinical, surgical and obstetrical diagnosis and treatment should not be the preserve of doctors, surgeons and obstetricians alone. Certain functions need to be assumed by lower skilled cadre of health workers in order to achieve a more sustainable skills match for wider health worker coverage. Different countries have a variety of indigenous health professionals trained locally. There are “Clinical Officers” in Malawi and Zambia, “Surgical and Medical Technicians” in Mozambique, “Assistant Medical Officers” with surgical and obstetric skills in Tanzania, and “Medical Assistants” in Ghana. The Medical licentiates and clinical officers in Tanzania have been trained to diagnose, treat and prescribe and can therefore fulfill many of the functions in district hospitals that the shortage of doctors would otherwise have made impossible. Nurse practitioners in Swaziland and enrolled nurses in Malawi have likewise played immense roles in their health systems, particularly in remote areas where it is difficult to get better-qualified health professionals to practice. These cadres typically have 2–3 years post-secondary training rather that the 5–6 required for training medical doctors.

Improve the Distribution of Human Resources

Equitable distribution of health workers is always a dilemma is sub-Saharan countries. The remote and under-developed areas with poor or no social amenities are always difficult to post staff to, without innovative incentives. Ghana’s ‘Deprived Area Incentive Scheme’ and Zambia’s “Health Workers Rural Retention Scheme”, that include housing or housing allowances, fast-track promotion and career development opportunities, car or car loans and education grants for staff children among other things, are seemingly successful in keeping doctors in under-served areas. These schemes now need to be extended to the other cadre of health workers to improve their distribution and retention in the most rural districts too.

The report on the High Level Forum on Health MDGs [

5] is very cautious about obligatory government service or “bonding” of newly-graduated health workers. The report contends that though the graduates can be posted to rural areas in obligatory government service, this means that these areas get the least experienced staff and that these graduates are often poorly supervised at a crucial stage in their career development. The report further states that obligatory service also tends to foster corruption as a ‘market’ emerges for transfers to more desirable posts. In extreme cases, obligatory social service may cause some graduates to emigrate.

Conclusion

The global health workforce crisis is immense and universal but its effects are certainly worse in sub-Saharan Africa. The crisis is as much a political as a fiscal one. Difficult political decisions must be made. Governments must have the political will to acknowledge the presence and extent of the crisis, and the commitment to convince their parliaments to approve the huge sums of money needed to tackle the different dimensions of and possible solutions for the crisis. Money freed up by debt relief should also target this immense crisis in the health sector. There is no “magic bullet” solution for the crisis but best practices and promising innovative interventions abound and should be shared and implemented. For these to succeed there must be close collaboration between governments, the private sector and the health workers themselves. Furthermore, there needs to be better dialogue and cooperation between developed “health worker-recipient” countries and developing “health worker-donor” countries, so that agreement can be reached on a more humane and mutually-beneficial migration of health workers. The Millenium Development Goals should not be achieved in some parts of the world at the expense of sub-Saharan African countries which, with the present levels of health worker availability and the incapacity to train more quickly enough, will undoubtedly not achieve the MDGs. It should be remembered that if remedial action seems too costly, inaction is definitely suicidal.