Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Motorized Traffic in Suburban–Rural Areas of a Metropolitan Region: Exploring Measurement Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

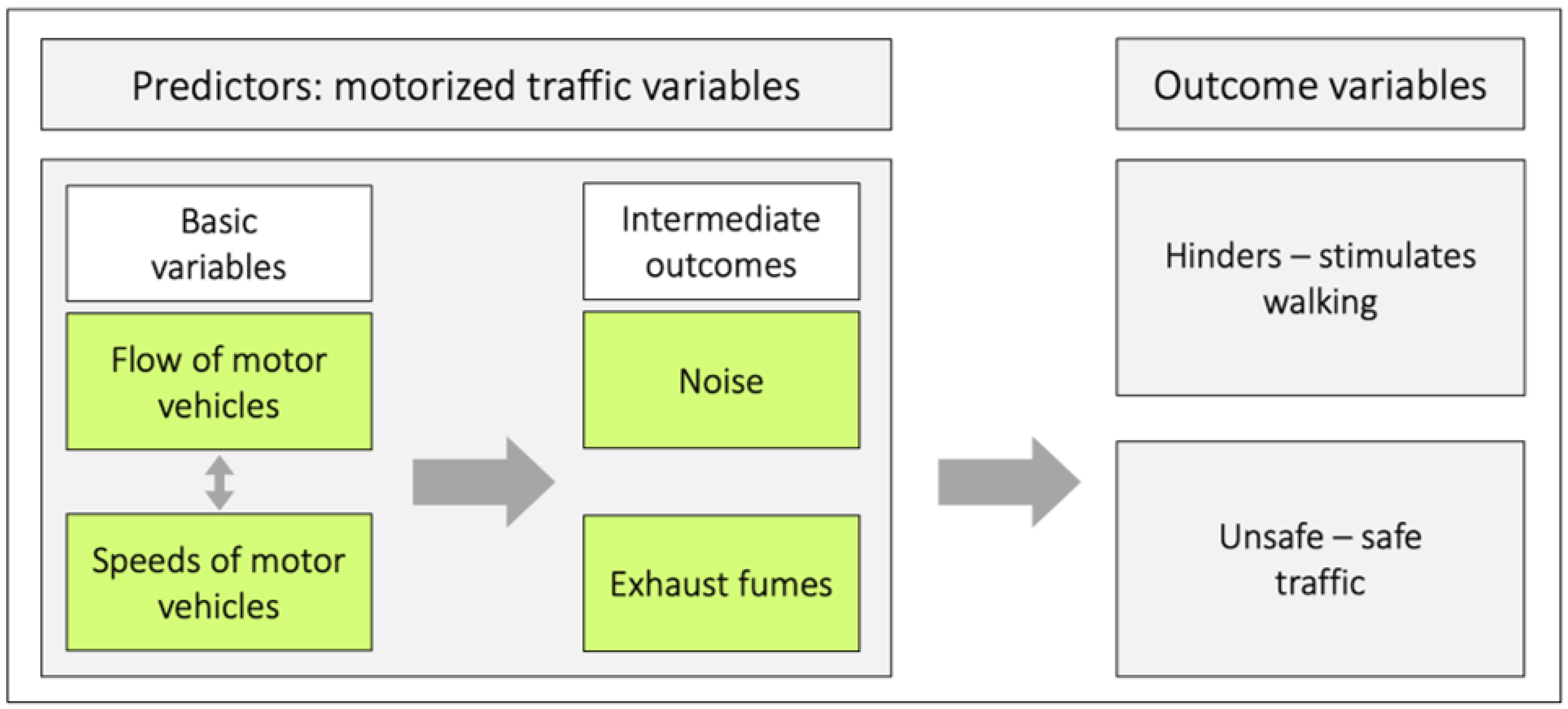

2. Method

2.1. Procedure and Participants

2.2. Descriptive Characteristics of the Participants

2.3. The Physically Active Commuting in Greater Stockholm Questionnaires (PACS Q1 and Q2)

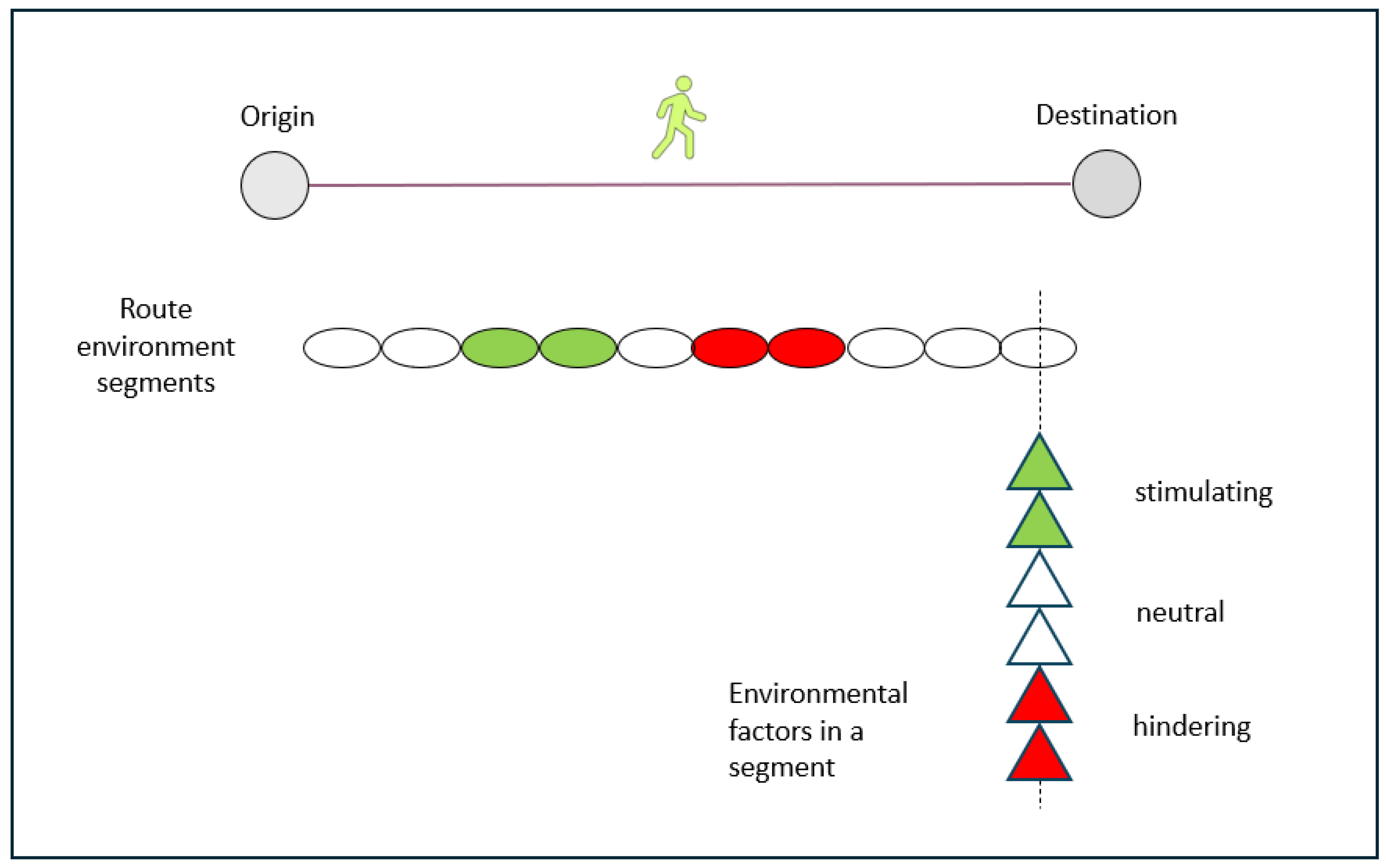

2.3.1. The Active Commuting Route Environment Scale (ACRES)

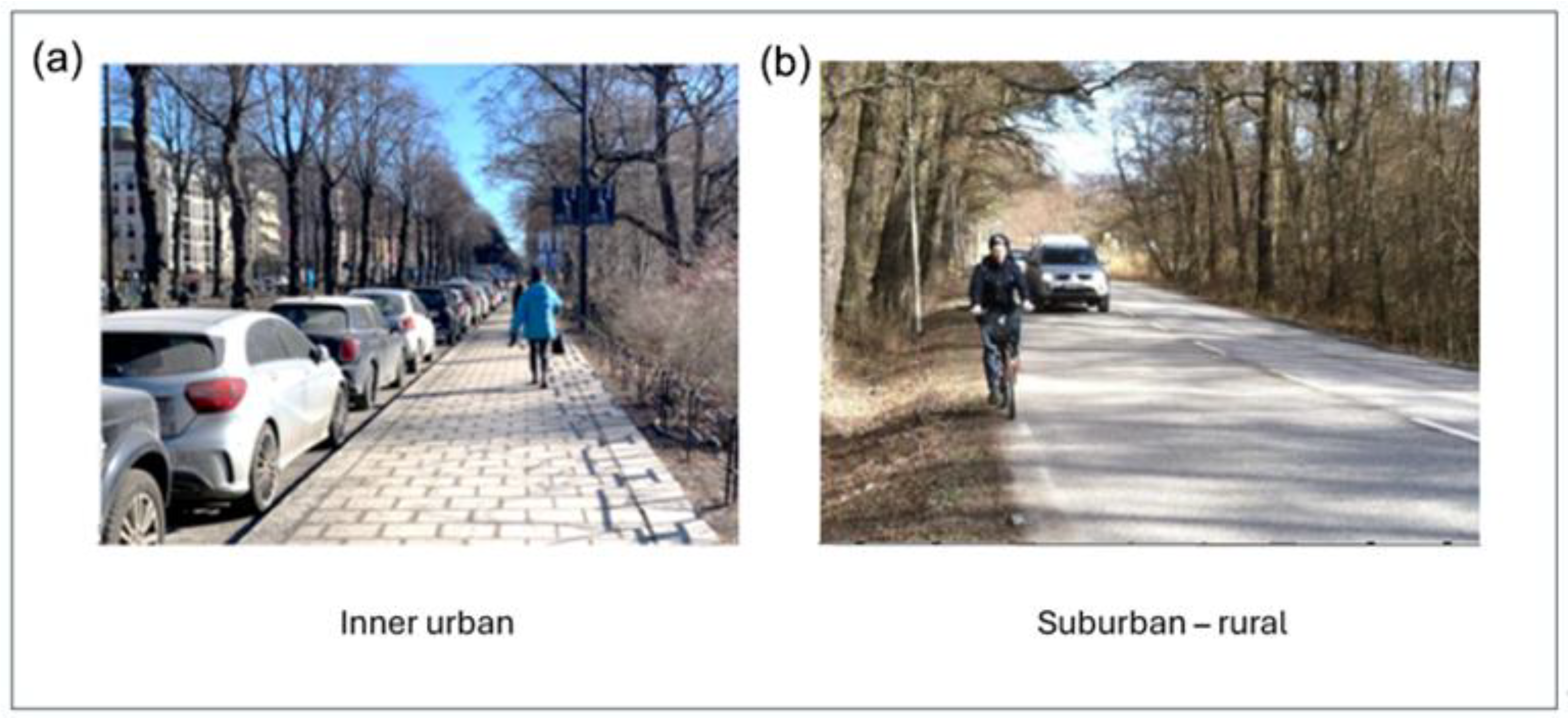

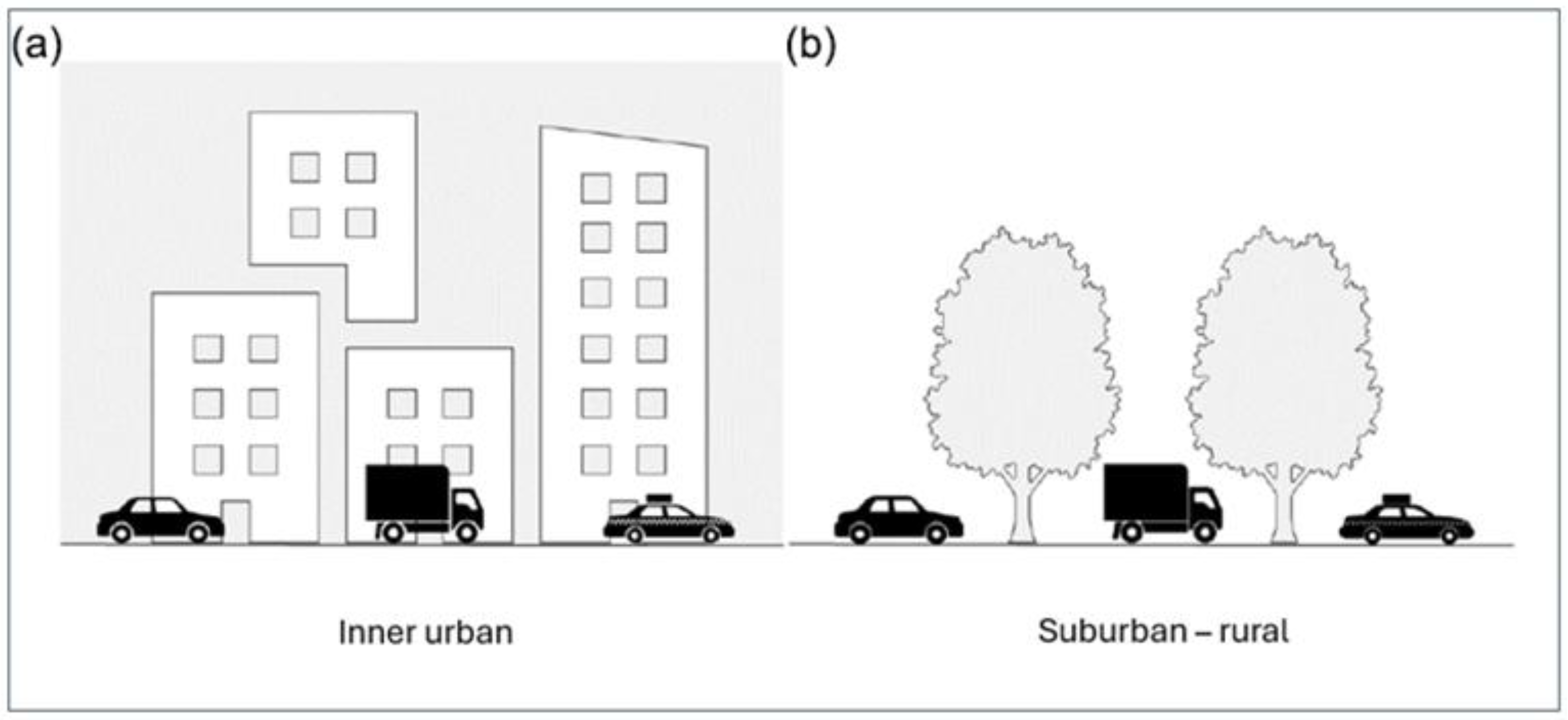

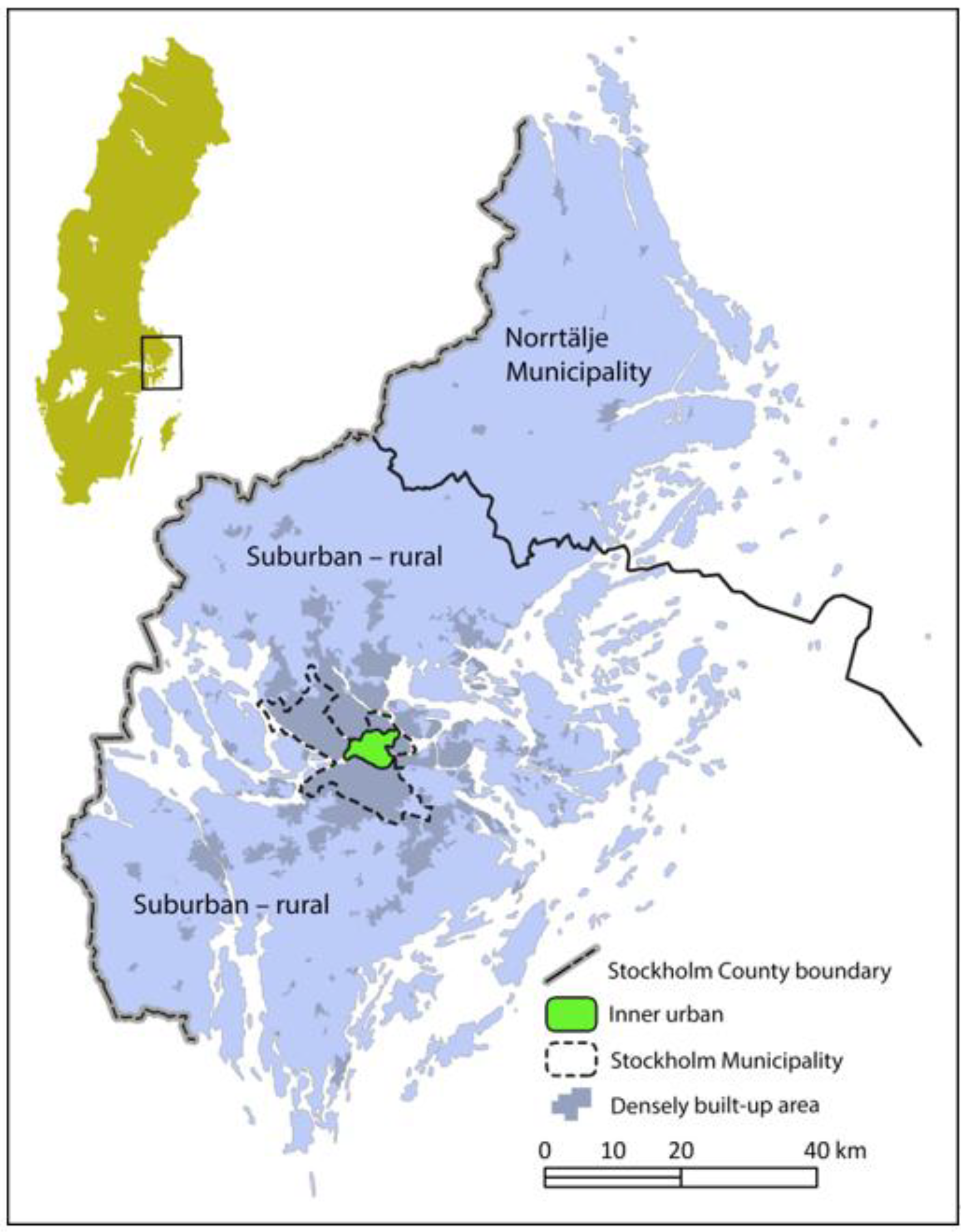

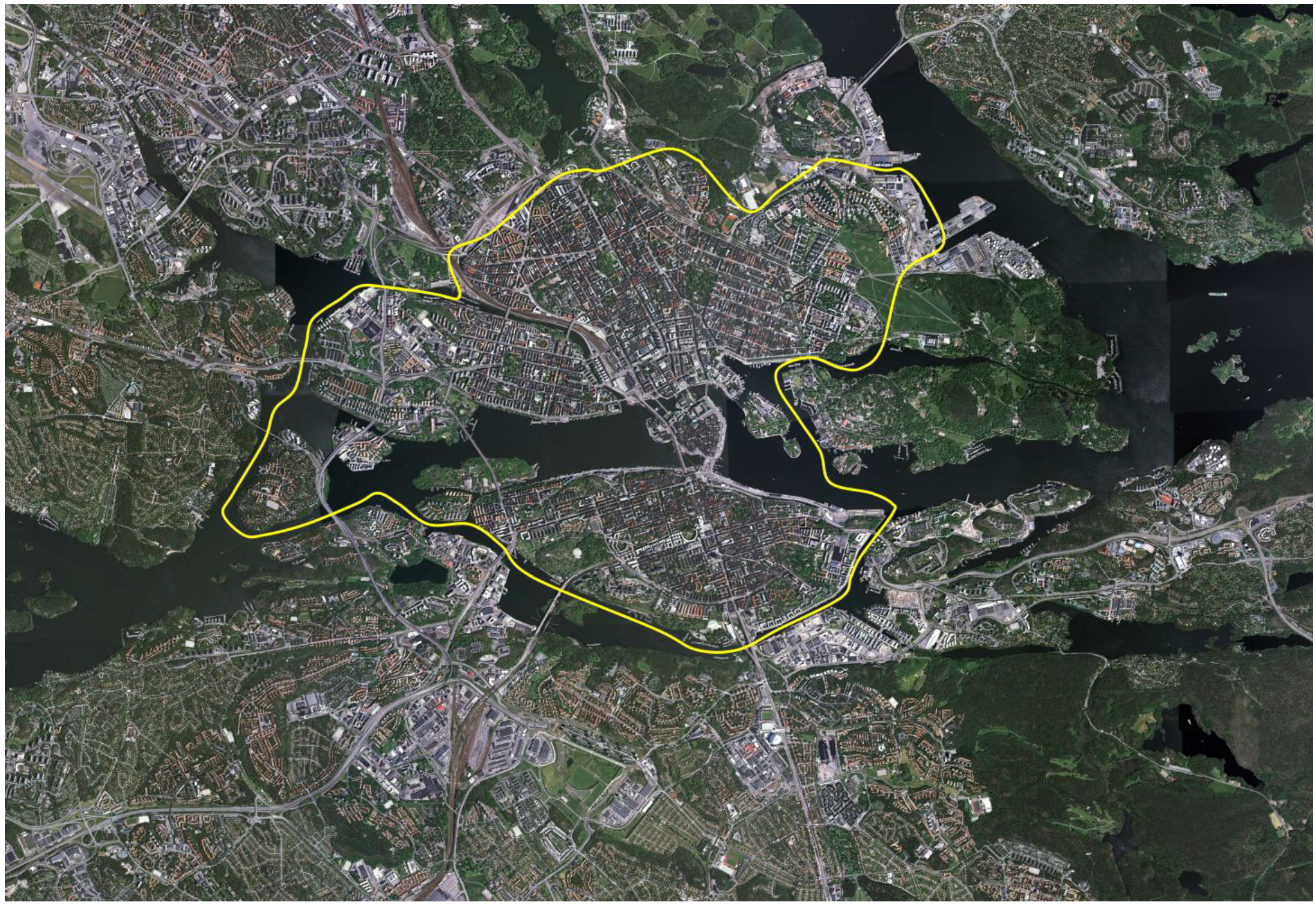

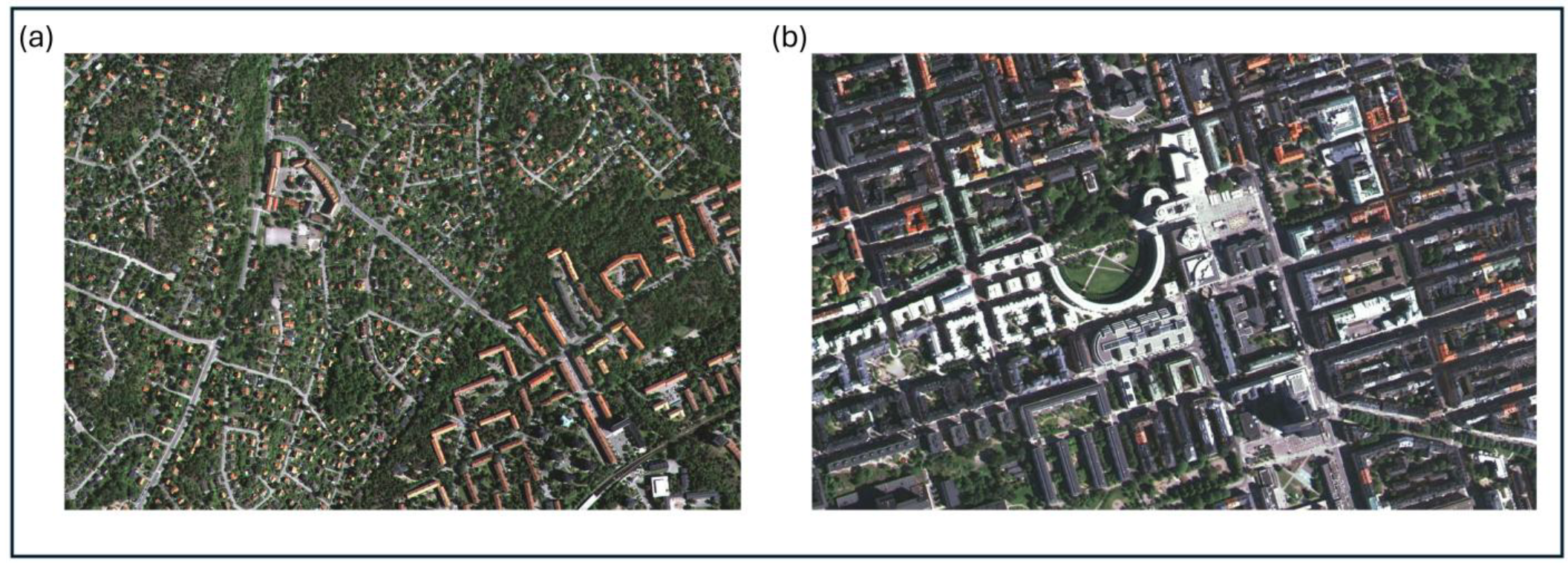

2.4. Study Area

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.5.1. Background Variables

2.5.2. Correlation Analyses (CA)

2.5.3. Multiple Regression Analyses (MRA)

2.5.4. Mediation Analyses (MA)

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of the Environmental Variables in Men and Women

3.2. Correlations Between the Environmental Variables

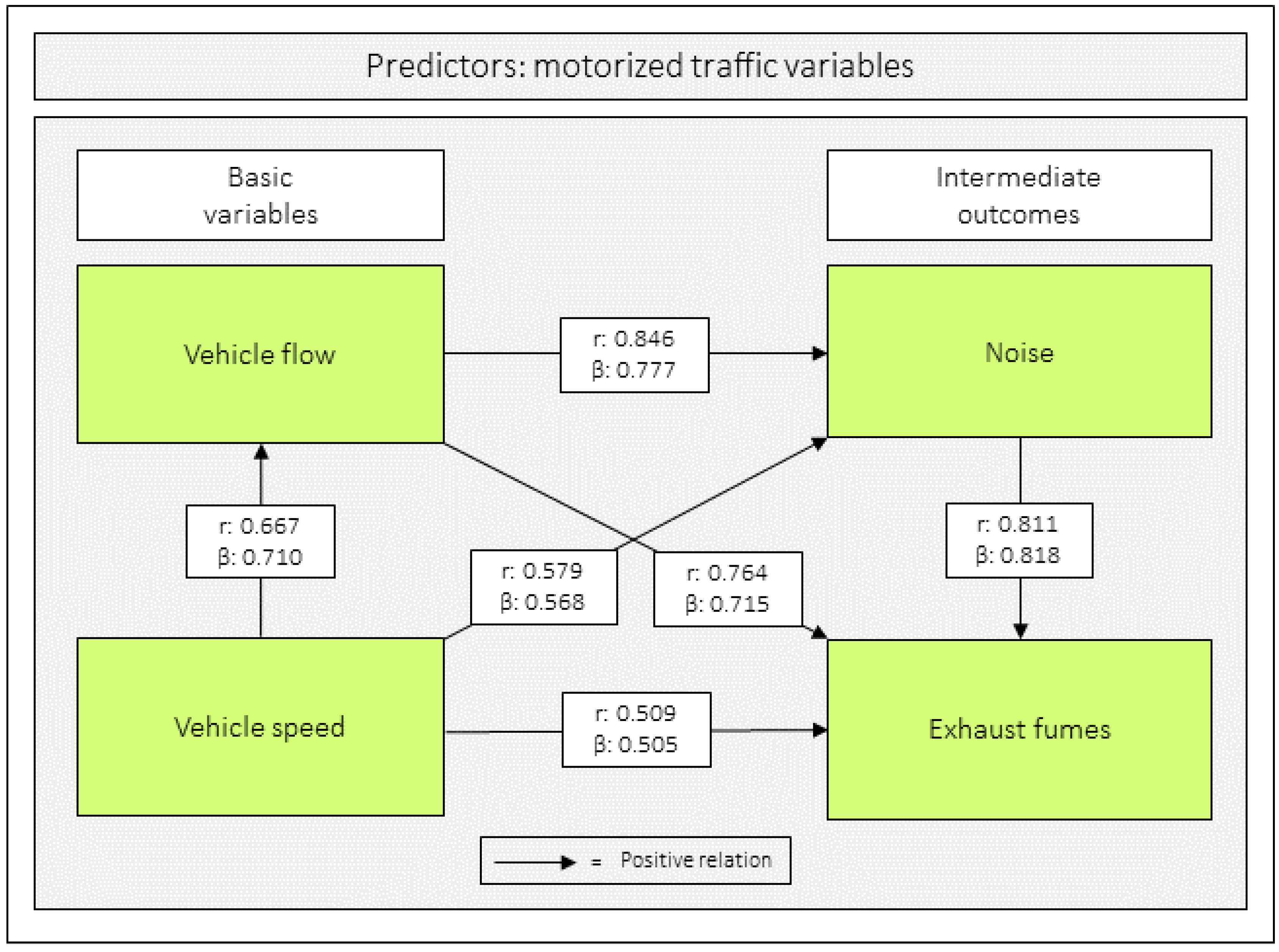

3.3. Relations Between the Predictor Variables

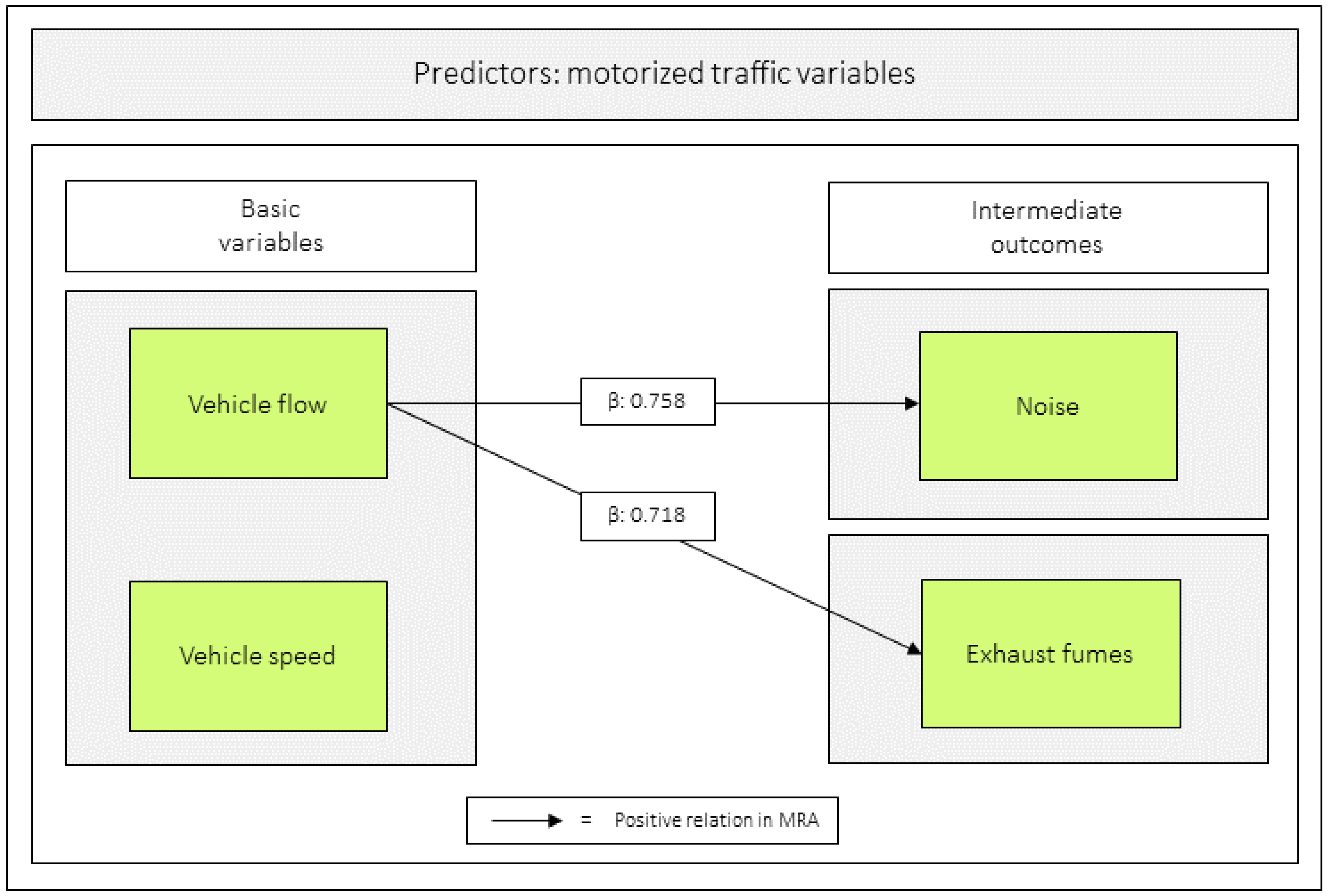

3.4. Relations Between the Basic Variables and the Intermediate Outcomes

3.5. Relations Between Individual Predictor Variables and the Outcome Hinders–Stimulates Walking

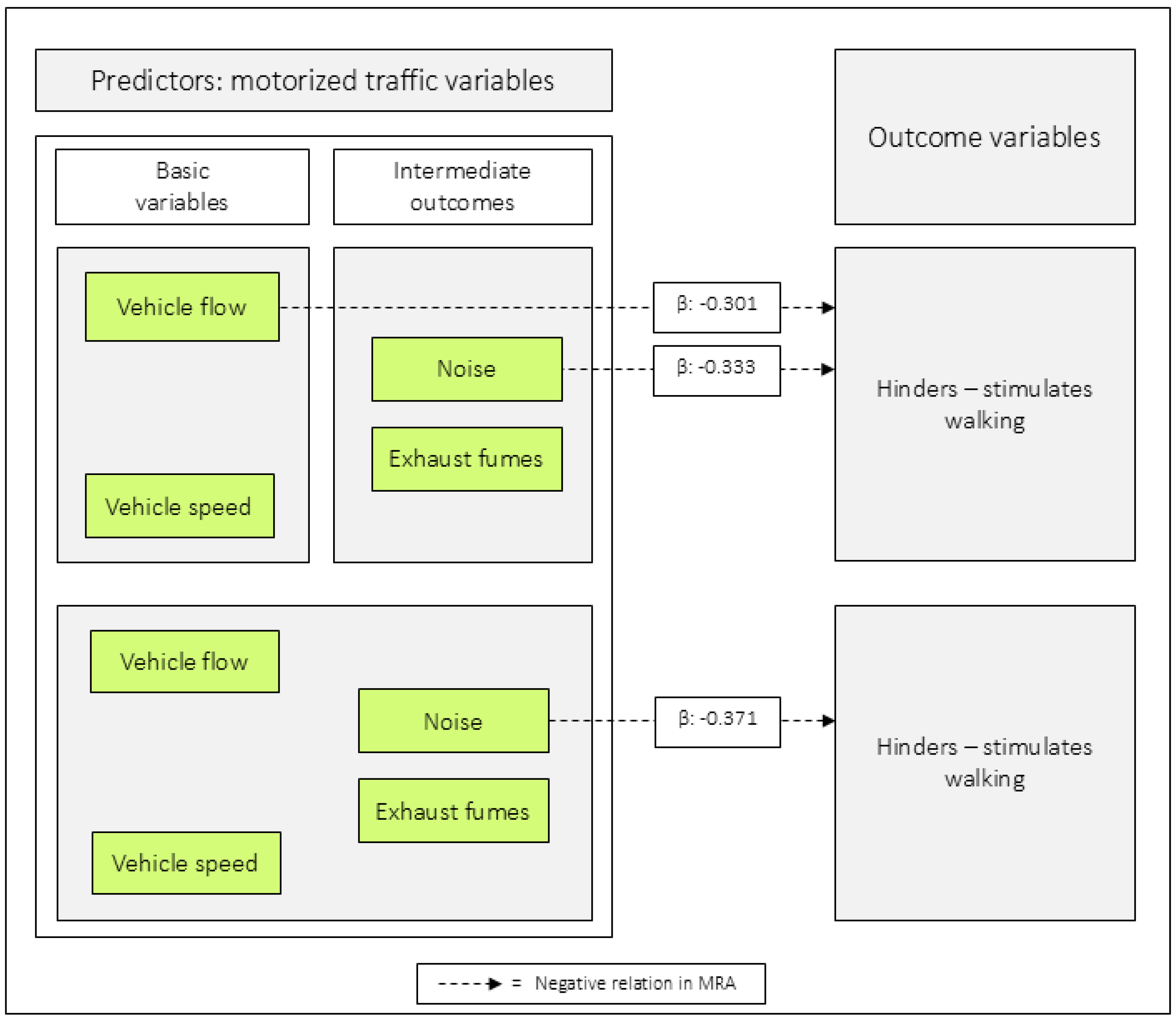

3.6. Relations Between Combinations of Predictor Variables and the Outcome Hinders–Stimulates Walking

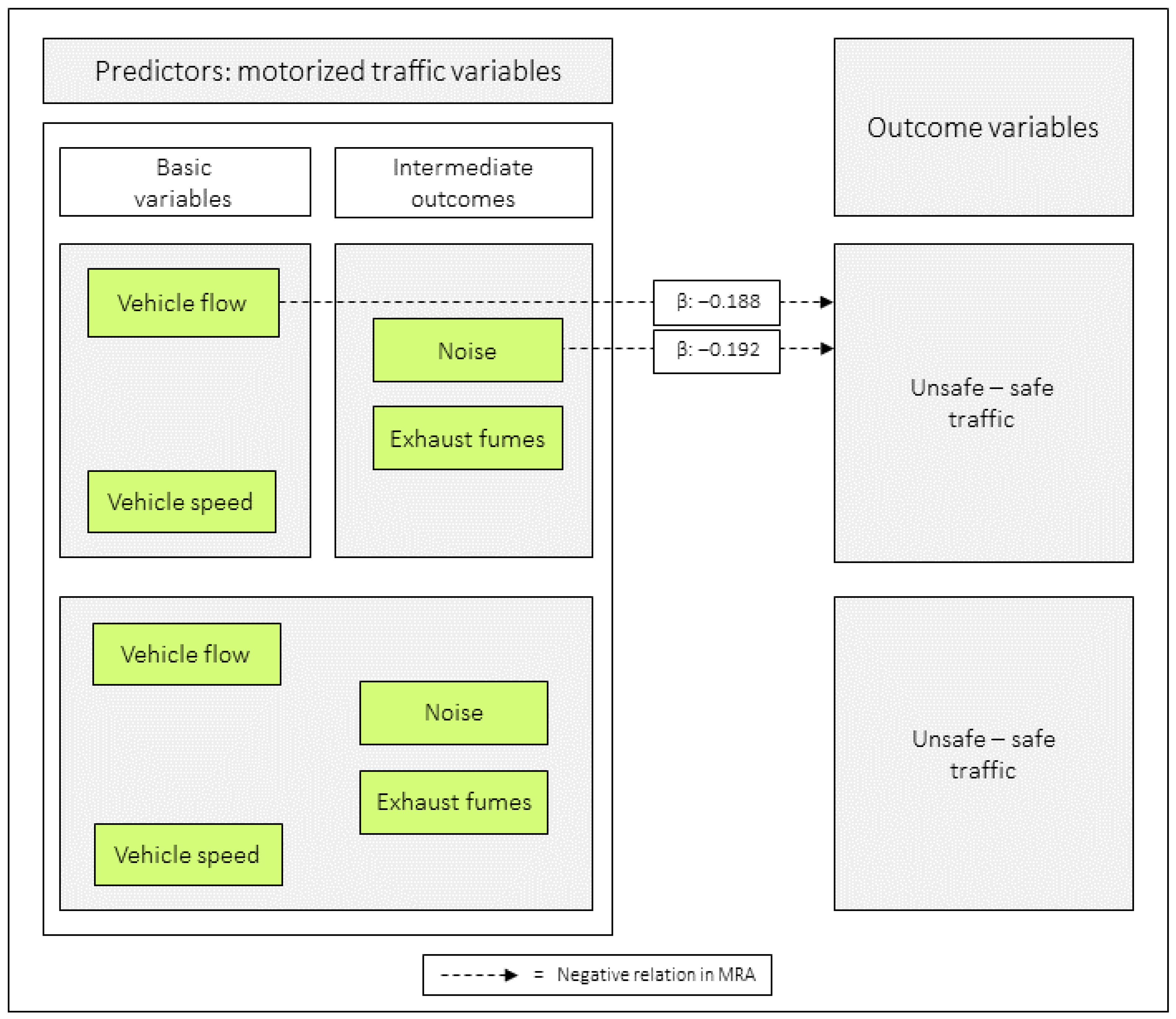

3.7. Relations Between Individual Predictor Variables and the Outcome Unsafe–Safe Traffic

3.8. Relations Between Combinations of Predictor Variables and Unsafe–Safe Traffic as an Outcome

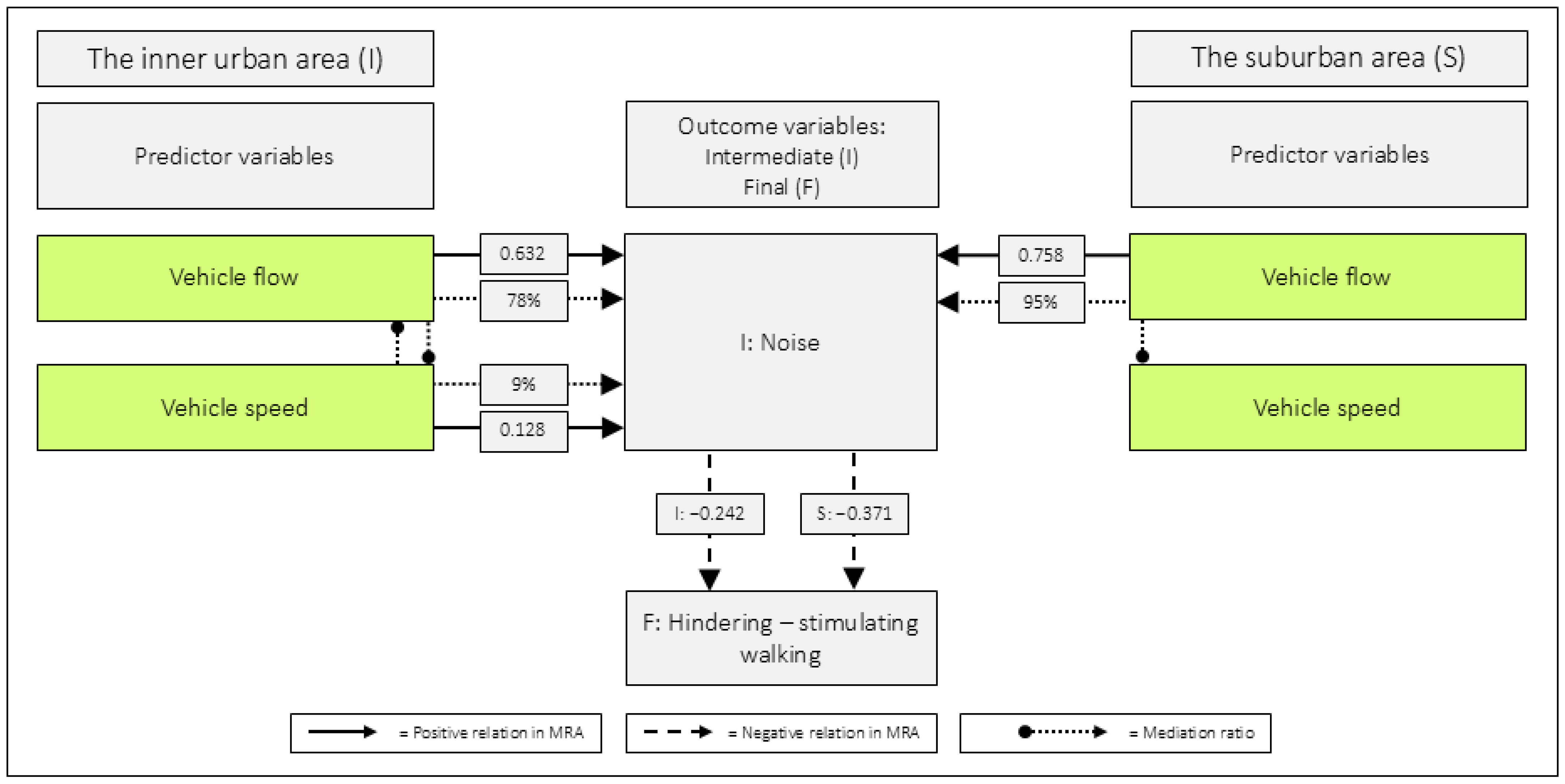

3.9. Mediation

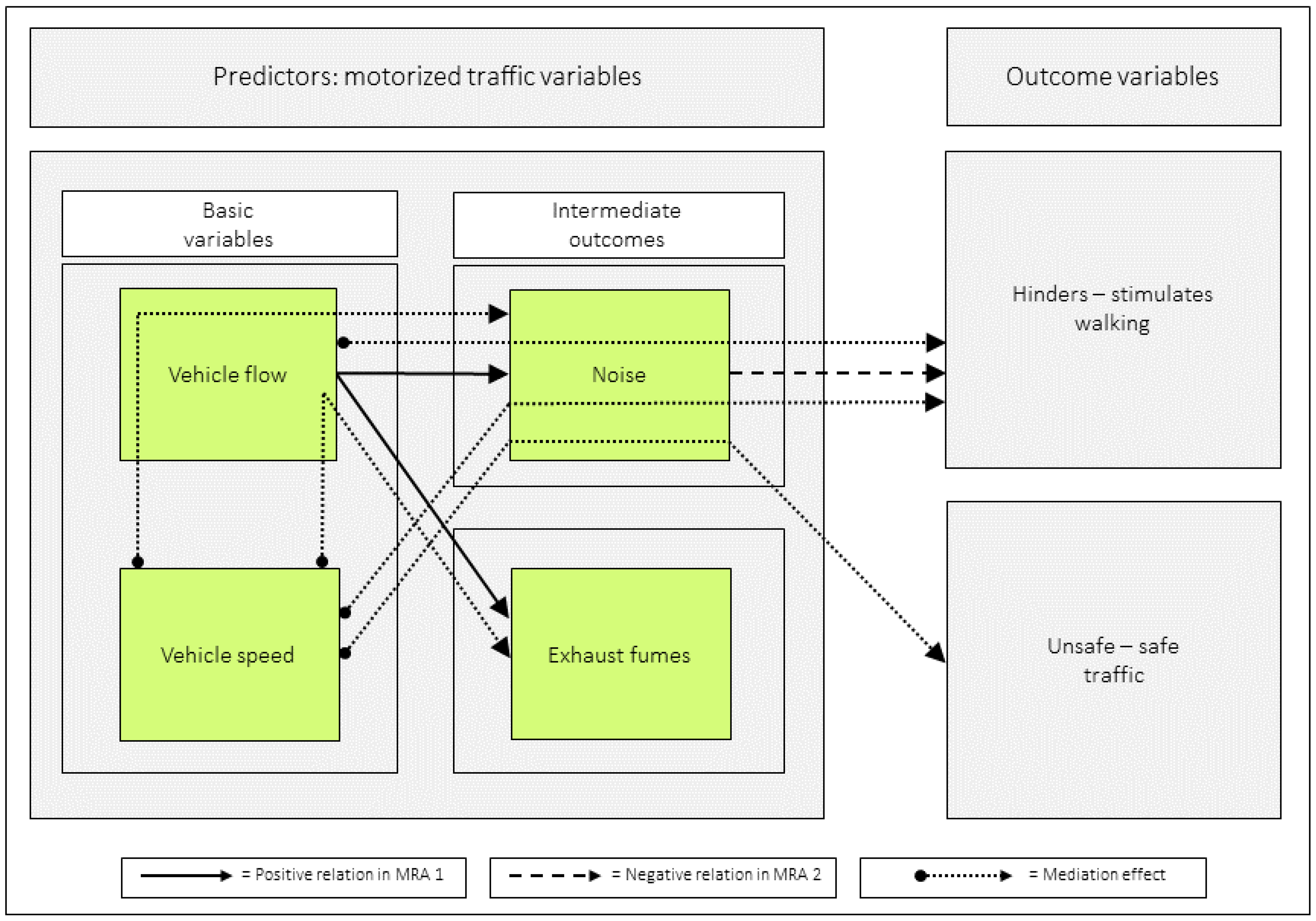

3.10. A Graphic Illustration of Significant Relations Based on the Commuting Pedestrians’ Perceptions and Appraisals of Their Route Environments

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationships Between Perceptions of the Predictor Variables of Motorized Traffic

4.2. Vehicle Speed and Vehicle Flow in Relation to Noise and Exhaust Fumes

4.3. The Motorized Traffic Variables in Relation to the Outcome Variable Hinders–Stimulates Walking

4.4. Comments on Relations Between Noise and Vehicle Flow

4.5. The Motorized Traffic Variables in Relation to the Outcome Variable Unsafe–Safe Traffic

4.6. External Validity in Relation to Different Subgroups in a Population

4.7. Exploring Measurement Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Distance | Duration | Speed | Frequency of Walking Trips in May | Total Number of Walking Trips over the Year * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | min | km · h−1 | trips · week−1 | ||

| Men | 3.94 ± 2.50 | 42.2 ± 22.8 | 5.42 ± 0.993 | 4.35 ± 3.57 | 219 ± 150 |

| (3.15–4.72) | (34.9–49.6) | (5.09–5.74) | (3.11–5.60) | (163–275) | |

| 41 | 39 | 39 | 34 | 30 | |

| Women | 2.92 ± 1.75 | 32.7 ± 18.6 | 5.14 ± 0.928 | 4.63 ± 4.61 | 227 ± 162 |

| (2.66–3.17) | (30.0–35.5) | (5.00–5.28) | (3.89–5.37) | (200–255) | |

| 181 | 175 | 175 | 151 | 135 |

| a.m. | 5–6 | >6–7 | >7–8 | >8–9 | >9–10 | >10 a.m.–<5 a.m. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 43) | n | 2 | 7 | 20 | 12 | 1 | 1 |

| % | 4.7 | 16.3 | 46.5 | 27.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | |

| Women (n = 187) | n | 3 | 34 | 89 | 39 | 9 | 13 |

| % | 1.6 | 18.2 | 47.6 | 20.9 | 4.8 | 7.0 |

| p.m. | 2–3 | >3–4 | >4–5 | >5–6 | >6–7 | >7–8 | >8 p.m.– <2 p.m. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 43) | n | 5 | 4 | 19 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 3 |

| % | 11.6 | 9.3 | 44.2 | 7.0 | 18.6 | 2.3 | 7.0 | |

| Women (n = 185) | n | 3 | 26 | 80 | 56 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| % | 1.6 | 14.1 | 43.2 | 30.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 6.5 |

| Model | Predictors | Outcomes | VIF | Cook | Std. Residual >(±3 SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Maximum | Mean | Maximum | N | Maximum | |||

| MRA 5:1 MA 9:1, 9:6, 9:8 | Vehicle speed | Noise | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.005 | 0.101 | 1 | 3.32 |

| MRA 5:2 MA 9:2, 9:5, 9:7 | Vehicle flow | Noise | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.172 | 3 | 4.85 |

| MRA 5:3 MA 9:3 | Vehicle speed | Exhaust fumes | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.005 | 0.086 | 1 | 3.06 |

| MRA 5:4 MA 9:4 | Vehicle flow | Exhaust fumes | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.141 | 5 | 4.03 |

| MRA 5:5 | Noise | Exhaust fumes | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.197 | 3 | −4.18 |

| MRA 5:6 MA 9:2, 9:4 | Vehicle speed | Vehicle flow | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.004 | 0.054 | – | – |

| MRA 6:1 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow | Noise | 1.38 | 1.92 | 0.005 | 0.189 | 3 | 4.90 |

| MRA 6:2 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow | Exhaust fumes | 1.38 | 1.92 | 0.005 | 0.130 | 5 | 4.01 |

| MRA A5:1 | Vehicle speed | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.005 | 0.054 | 1 | −3.06 |

| MRA A5:2 | Vehicle flow | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.046 | – | – |

| MRA A5:3 MA 9:5, 9:6, 9:9 | Noise | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.044 | – | – |

| MRA A5:4 | Exhaust fumes | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.10 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.111 | – | – |

| MRA 7:1 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.38 | 1.92 | 0.005 | 0.042 | – | – |

| MRA 7:2 | Noise Exhaust fumes | Hinders–stimulates walking | 1.76 | 3.09 | 0.005 | 0.095 | – | – |

| MRA 7:3 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow Noise Exhaust fumes | Hinders–stimulates walking | 2.34 | 4.67 | 0.005 | 0.087 | – | – |

| MRA A6:1 | Vehicle speed | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.004 | 0.077 | 4 | −3.56 |

| MRA A6:2 | Vehicle flow | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.004 | 0.060 | 4 | −3.58 |

| MRA A6:3 MA 9:7, 9:8, 9:10 | Noise | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.004 | 0.054 | 2 | −3.55 |

| MRA A6:4 | Exhaust fumes | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.10 | 1.20 | 0.004 | 0.049 | 4 | −3.61 |

| MRA 8:1 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.38 | 1.92 | 0.004 | 0.067 | 5 | −3.57 |

| MRA 8:2 | Noise Exhaust fumes | Unsafe–safe traffic | 1.76 | 3.09 | 0.004 | 0.049 | 3 | −3.57 |

| MRA 8:3 | Vehicle speed Vehicle flow Noise Exhaust fumes | Unsafe–safe traffic | 2.34 | 4.67 | 0.004 | 0.067 | 5 | −3.57 |

| MA 9:1, 9:3 | Vehicle flow | Vehicle speed | 1.12 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.059 | – | – |

| MA 9:9, 9:10 | Composite variable | Noise | 1.11 | 1.20 | 0.005 | 0.174 | 1 | 4.63 |

| Total | 1.31 | 4.67 | 0.005 | 0.197 | 50 | 4.90 | ||

| Model | Outcome | y-Intercept (95% CI) | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A5:1 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 10.1 (7.65–12.5) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | −0.199 (−0.299 to −0.100) | <0.001 | 0.122 |

| A5:2 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 11.4 (9.08–13.7) | <0.001 | Vehicle flow | −0.292 (−0.380 to −0.205) | <0.001 | 0.211 |

| A5:3 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 12.3 (10.1–14.5) | <0.001 | Noise | −0.389 (−0.478 to −0.300) | <0.001 | 0.292 |

| A5:4 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 11.4 (9.18–13.6) | <0.001 | Exhaust fumes | −0.331 (−0.422 to −0.240) | <0.001 | 0.235 |

| Model | Outcome | y-Intercept (95% CI) | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A6:1 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 14.6 (12.1–17.2) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | −0.254 (−0.360 to −0.147) | <0.001 | 0.076 |

| A6:2 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 15.0 (12.4–17.5) | <0.001 | Vehicle flow | −0.262 (−0.359 to −0.164) | <0.001 | 0.097 |

| A6:3 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 14.8 (12.3–17.4) | <0.001 | Noise | −0.261 (−0.366 to −0.155) | <0.001 | 0.082 |

| A6:4 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 14.4 (11.8–16.9) | <0.001 | Exhaust fumes | −0.235 (−0.340 to −0.131) | <0.001 | 0.067 |

References

- Hall, K.S.; Hyde, E.T.; Bassett, D.R.; Carlson, S.A.; Carnethon, M.R.; Ekelund, U.; Evenson, K.R.; Galuska, D.A.; Kraus, W.E.; Lee, I.M.; et al. Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.; Kahlmeier, S.; Götschi, T.; Orsini, N.; Richards, J.; Roberts, N.; Scarborough, P.; Foster, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of reduction in all-cause mortality from walking and cycling and shape of dose response relationship. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.N.; Hardman, A.E. Walking to health. Sports Med. 1997, 23, 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Walking and Cycling: Latest Evidence to Support Policy-Making and Practice; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Mora, R.; Vejares, P. Perception of the built environment and walking in pericentral neighbourhoods in Santiago, Chile. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Gong, Y. The smart city and healthy walking: An environmental comparison between healthy and the shortest route choices. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panter, J.; Griffin, S.; Ogilvie, D. Active commuting and perceptions of the route environment: A longitudinal analysis. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Robertson-Wilson, J.; Wood, L.; Falconer, R. The role of the changing built environment in shaping our shape. In Geographies of Obesity: Environmental Understanding of the Obesity Epidemic; Pearce, J., Witten, K., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.B.; Chen, D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittaels, H.; Verloigne, M.; Gidlow, C.; Gloanec, J.; Titze, S.; Foster, C.; Oppert, J.M.; Rutter, H.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M.; et al. Measuring physical activity-related environmental factors: Reliability and predictive validity of the European environmental questionnaire ALPHA. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittaels, H.; Foster, C.; Oppert, J.-M.; Rutter, H.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Assessment of environmental correlates of physical activity: Development of a European questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.J.; Goodman, A.; Sahlqvist, S.; Bull, F.C.; Ogilvie, D. Correlates of walking and cycling for transport and recreation: Factor structure, reliability and behavioural associations of the perceptions of the environment in the neighbourhood scale (PENS). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, N.; Owen, N.; Iverson, D.; Leslie, E.; Bauman, A. Perceived environment attributes, residential location, and walking for particular purposes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, P. Physical activity behaviours and environmental well-being in a spatial context. In Geography and Health—A Nordic Outlook; Schaerström, A., Jörgensen, S.H., Kistemann, T., Sivertun, Å., Eds.; Swedish National Defence College: Stockholm, Sweden; Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU): Trondheim, Norway; Universität Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 2014; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, D. Exploring Perceptions of Route Environments in Relation to Walking. Ph.D. Thesis, The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, GIH, Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, D.; Wahlgren, L.; Olsson, K.S.E.; Schantz, P. Pedestrians’ perceptions of motorized traffic variables in relation to appraisals of urban route environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, D.; Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Pedestrians’ perceptions of route environments in relation to deterring or facilitating walking. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1012222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Exploring bikeability in a suburban metropolitan area using the active commuting route environment scale (ACRES). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 8276–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Exploring bikeability in a metropolitan setting: Stimulating and hindering factors in commuting route environments. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, N.M.; Coffee, N.T.; Nolan, R.; Dollman, J.; Sugiyama, T. Neighbourhood environmental attributes associated with walking in South Australian adults: Differences between urban and rural areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlgren, L.; Stigell, E.; Schantz, P. The active commuting route environment scale (ACRES): Development and evaluation. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Bikeability and methodological issues using the active commuting route environment scale (ACRES) in a metropolitan setting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, P.; Salier Eriksson, J.; Rosdahl, H. The heart rate method for estimating oxygen uptake: Analyses of reproducibility using a range of heart rates from cycle commuting. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics. Statistical Year-Book of Stockholm 2007; Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Dimitrova, D.D. Green spaces and environmental noise perception. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlöf-Gunnarsson, A.; Öhrström, E. Noise and well-being in urban residential environments: The potential role of perceived availability to nearby green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunds, K.S.; Casper, J.M.; Hipp, J.A.; Koenigstorfer, J. Recreational walking decisions in urban away-from-home environments: The relevance of air quality, noise, traffic, and the natural environment. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 65, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, H.; Stark, K.; Jarass, J. How are air pollution and noise perceived en route? Investigating cyclists’ and pedestrians’ personal exposure, wellbeing and practices during commute. J. Transp. Health 2022, 24, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, S.; Ruiz, T.; Mars, L. A qualitative study on the role of the built environment for short walking trips. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 33, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådsten-Ekman, M.; Vincent, B.; Anselme, C.; Mandon, A.; Rohr, R.; Defrance, J.; Van Maercke, D.; Botteldooren, D.; Nilsson, M.E. Case-study evaluation of a low and vegetated noise barrier in an urban public space. In Proceedings of the 40th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering 2011, INTER-NOISE, Osaka, Japan, 4–7 September 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hahad, O.; Prochaska, J.H.; Daiber, A.; Muenzel, T. Environmental noise-induced effects on stress hormones, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction: Key factors in the relationship between cerebrocardiovascular and psychological disorders. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4623109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Gori, T.; Babisch, W.; Basner, M. Cardiovascular effects of environmental noise exposure. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basner, M.; McGuire, S. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: A systematic review on environmental noise and effects on sleep. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kempen, E.; Casas, M.; Pershagen, G.; Foraster, M. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: A systematic review on environmental noise and cardiovascular and metabolic effects: A summary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, C.; Pyko, A.; Lind, T.; Pershagen, G.; Georgelis, A. Traffic Noise in the Population: Exposure, Vulnerable Groups and Negative Consequences; Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foraster, M.; Eze, I.C.; Vienneau, D.; Brink, M.; Cajochen, C.; Caviezel, S.; Heritier, H.; Schaffner, E.; Schindler, C.; Wanner, M.; et al. Long-term transportation noise annoyance is associated with subsequent lower levels of physical activity. Environ. Int. 2016, 91, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardell, L.; Pehrson, K. Stockholmers Outdoors: Use of Nature Areas. A Mail Questionnaire and a Home Interview Study; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala, Sweden, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anciaes, P.R.; Stockton, J.; Ortegon, A.; Scholes, S. Perceptions of road traffic conditions along with their reported impacts on walking are associated with wellbeing. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 15, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, A.P.; Evenson, K.R.; Herring, A.H.; Huston, S.L.; Rodriguez, D.A. Exploring associations between physical activity and perceived and objective measures of the built environment. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay-Vega, L.; Hastings, A.; Pollard, J.K.; Zuschlag, M.; Stearns, M.D. Quieter Cars and the Safety of Blind Pedestrians: Phase I; U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, L.; Skov, R. Noise from Electric Vehicles—Measurements; Vejdirektoratet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonzo, M.A. To walk or not to walk? The hierarchy of walking needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadpour, S.; Pakzad, J.; Khankeh, H. Understanding the influence of environment on adults’ walking experiences: A meta-synthesis study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.; Teschke, K. Route preferences among adults in the near market for bicycling: Findings of the cycling in cities study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2010, 25, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Characteristics of the Participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Females **, % | 82 | |

| Age in years **, mean ± SD | 50.0 ± 9.8 | |

| Weight in kg, mean ± SD | 68.4 ± 10.4 | |

| Height in cm, mean ± SD | 169.9 ± 7.8 | |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 23.7 ± 3.0 | |

| Gainful employment, % | 97 | |

| Educated at university level **, % | 70 | |

| Income **: | ≤25,000 SEK *** a month, % | 53 |

| 25,001–30,000 SEK *** a month, % | 28 | |

| ≥30,001 SEK *** a month, % | 18 | |

| Participant and both parents born in Sweden, % | 83 | |

| Having a driver’s licence, % | 88 | |

| Usually access to a car, % | 70 | |

| Leaving home 7–9 a.m. to walk to work or study, % | 70 | |

| Leaving place of work or study 4–6 p.m. to walk home, % | 69 | |

| Number of walking-commuting trips per year ****, mean ± SD | 226 ± 159 | |

| Overall physical health either good or very good, % | 72 | |

| Overall mental health either good or very good, % | 82 | |

| Variable | Ratings and Verbal Anchors | Variable Name | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 15 | ||

| How do you find the flow of motor vehicles (number of cars) along your route? | Very low | Neither low nor high | Very high | Flow of motor vehicles ** |

| How do you find the speeds of motor vehicles (taxis, lorries, ordinary cars, buses) along your route? | Very low | Neither low nor high | Very high | Speeds of motor vehicles *** |

| How do you find the noise levels along your route? | Very low | Neither low nor high | Very high | Noise |

| How do you find the exhaust fume levels along your route? | Very low | Neither low nor high | Very high | Exhaust fumes |

| Do you think that, on the whole, the environment you walk in stimulates/hinders your commuting? | Hinders a lot | Neither hinders nor stimulates | Stimulates a lot | Hinders–stimulates walking * |

| How unsafe/safe do you feel in traffic as a pedestrian along your route? | Very unsafe | Neither unsafe nor safe | Very safe | Unsafe–safe traffic * |

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinders–Stimulates Walking * | Unsafe–Safe Traffic | Vehicle Speed | Vehicle Flow | Noise | Exhaust Fumes | |

| Men (n = 43) | 10.3 | 12.0 | 8.37 | 7.05 | 7.09 | 6.60 |

| 3.30 | 3.09 | 3.72 | 3.81 | 3.57 | 3.42 | |

| (9.26–11.3) | (11.0–12.9) | (7.23–9.52) | (5.87–8.22) | (5.99–8.19) | (5.55–7.66) | |

| Women (n =190) | 11.4 | 12.2 | 7.75 | 6.66 | 6.54 | 6.49 |

| 2.99 | 3.22 | 3.81 | 4.29 | 4.01 | 4.03 | |

| (11.0–11.9) | (11.7–12.7) | (7.20–8.29) | (6.04–7.27) | (5.97–7.12) | (5.92–7.07) | |

| Hinders–Stimulates Walking | Unsafe–Safe Traffic | Vehicle Speed | Vehicle Flow | Noise | Exhaust Fumes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinders–stimulates walking | – | |||||

| Unsafe–safe traffic | 0.264 * | – | ||||

| Vehicle speed | −0.286 * | −0.302 * | – | |||

| Vehicle flow | −0.441 * | −0.335 * | 0.667 * | – | ||

| Noise | −0.532 * | −0.314 * | 0.579 * | 0.846 * | – | |

| Exhaust fumes | −0.456 * | −0.287 * | 0.509 * | 0.764 * | 0.811 * | – |

| Model | Outcome | y-Intercept | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||||||

| 5:1 | Noise | 5.22 | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | 0.568 | <0.001 | 0.366 |

| (2.61–7.84) | (0.460–0.677) | ||||||

| 5:2 | Noise | 2.16 | 0.017 | Vehicle flow | 0.777 | <0.001 | 0.713 |

| (0.393–3.92) | (0.709–0.844) | ||||||

| 5:3 | Exhaust fumes | 5.14 | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | 0.505 | <0.001 | 0.263 |

| (2.33–7.95) | (0.389–0.622) | ||||||

| 5:4 | Exhaust fumes | 2.12 | 0.052 | Vehicle flow | 0.715 | <0.001 | 0.577 |

| (−0.017–4.25) | (0.633–0.797) | ||||||

| 5:5 | Exhaust fumes | 1.30 | 0.187 | Noise | 0.818 | <0.001 | 0.654 |

| (−0.637–3.25) | (0.739–0.898) | ||||||

| 5:6 | Vehicle flow | 4.19 | 0.001 | Vehicle speed | 0.710 | <0.001 | 0.469 |

| (1.64–6.74) | (0.604–0.816) |

| Model | Intermediate Outcome | y-Intercept (95% CI) | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6:1 | Noise | 2.05 (0.25–3.85) | 0.026 | Vehicle speed | 0.031 (−0.067–0.128) | 0.536 | 0.712 |

| Vehicle flow | 0.758 (0.668–0.848) | <0.001 | |||||

| 6:2 | Exhaust fumes | 2.13 (−0.05–4.32) | 0.055 | Vehicle speed | −0.004 (−0.122–0.114) | 0.945 | 0.575 |

| Vehicle flow | 0.718 (0.608–0.827) | <0.001 |

| Model | Outcome | y-Intercept (95% CI) | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7:1 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 11.3 (8.98–13.7) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | 0.014 (−0.112–0.140) | 0.822 | 0.208 |

| Vehicle flow | −0.301 (−0.418 to −0.184) | <0.001 | |||||

| 7:2 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 12.4 (10.2–14.6) | <0.001 | Noise | −0.333 (−0.483 to −0.183) | <0.001 | 0.292 |

| Exhaust fumes | −0.068 (−0.215–0.079) | 0.361 | |||||

| 7:3 | Hinders–stimulates walking | 12.2 (10.0–14.5) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | 0.025 (−0.094–0.145) | 0.677 | 0.287 |

| Vehicle flow | 0.037 (−0.133–0.207) | 0.668 | |||||

| Noise | −0.371 (−0.555 to −0.186) | <0.001 | |||||

| Exhaust fumes | −0.080 (−0.232–0.072) | 0.301 |

| Model | Outcome | y-Intercept (95% CI) | p-Value | Predictor | Unstandardized B (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8:1 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 15.4 (12.8–18.0) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | −0.120 (−0.260–0.019) | 0.089 | 0.104 |

| Vehicle flow | −0.188 (−0.317 to −0.059 | 0.005 | |||||

| 8:2 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 14.9 (12.4–17.5) | <0.001 | Noise | −0.192 (−0.369 to −0.015) | 0.033 | 0.082 |

| Exhaust fumes | −0.084 (−0.258–0.090) | 0.343 | |||||

| 8:3 | Unsafe–safe traffic | 15.6 (13.0–18.2) | <0.001 | Vehicle speed | −0.119 (−0.259–0.021) | 0.095 | 0.100 |

| Vehicle flow | −0.113 (−0.312–0.086) | 0.264 | |||||

| Noise | −0.058 (−0.273–0.157) | 0.596 | |||||

| Exhaust fumes | −0.043 (−0.221–0.135) | 0.634 |

| Model | Predictor (X) | Mediator (M) | Outcome (Y) | Standardized Total Effect of X on Y | Standardized Direct Effect of X on Y | Standardized Indirect Effect of X on Y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | p-Value | b | p-Value | b | 95% CI | % of Total Effect * | ||||

| MA 9:1 | Vehicle flow | Vehicle speed | Noise | 0.829 | <0.001 | 0.809 | <0.001 | 0.020 | −0.050–0.087 | 2 |

| MA 9:2 | Vehicle speed | Vehicle flow | Noise | 0.548 | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.536 | 0.518 | 0.433–0.605 | 95 |

| MA 9:3 | Vehicle flow | Vehicle speed | Exhaust fumes | 0.766 | <0.001 | 0.768 | <0.001 | −0.003 | −0.084–0.082 | 0 |

| MA 9:4 | Vehicle speed | Vehicle flow | Exhaust fumes | 0.489 | <0.001 | −0.004 | 0.945 | 0.493 | 0.400–0.587 | 101 |

| MA 9:5 | Vehicle flow | Noise | Hinders–stimulates walking | −0.399 | <0.001 | 0.042 | 0.687 | −0.441 | −0.609 to −0.288 | 111 |

| MA 9:6 | Vehicle speed | Noise | Hinders–stimulates walking | −0.246 | <0.001 | 0.039 | 0.566 | −0.285 | −0.379 to −0.195 | 116 |

| MA 9:7 | Vehicle flow | Noise | Unsafe–safe traffic | −0.344 | <0.001 | −0.252 | 0.033 | −0.092 | −0.274–0.082 | 27 |

| MA 9:8 | Vehicle speed | Noise | Unsafe–safe traffic | −0.301 | <0.001 | −0.184 | 0.017 | −0.117 | −0.224 to −0.028 | 39 |

| MA 9:9 | Composite variable | Noise | Hinders–stimulates walking | −0.349 | <0.001 | 0.089 | 0.330 | −0.438 | −0.595 to −0.298 | 126 |

| MA 9:10 | Composite variable | Noise | Unsafe–safe traffic | −0.330 | <0.001 | −0.212 | 0.041 | −0.118 | −0.290–0.047 | 36 |

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinders–Stimulates Walking | Unsafe–Safe Traffic | Vehicle Speed | Vehicle Flow | Noise | Exhaust Fumes | |

| Inner urban (n = 294) | 10.4 ± 2.97 | 10.9 ± 3.40 | 9.57 ± 3.08 | 10.2 ± 3.66 | 9.87 ± 3.28 | 9.74 ± 3.46 |

| Suburban (n = 233) | 11.2 ± 3.07 | 12.2 ± 3.19 | 7.86 ± 3.79 | 6.73 ± 4.20 | 6.64 ± 3.93 | 6.52 ± 3.92 |

| Ratio inner urban/suburban | 0.93 | 0.89 | 1.22 | 1.52 | 1.49 | 1.49 |

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinders–Stimulates Cycling | Unsafe–Safe Traffic | Vehicle Speed | Vehicle Flow | Noise | Exhaust Fumes | |

| Inner urban (n = 821) | 9.16 ± 3.32 | 8.53 ± 3.69 | 9.45 ± 2.83 | 11.1 ± 3.34 | 9.62 ± 3.04 | 9.91 ± 3.15 |

| Suburban (n = 1098) | 11.3 ± 2.84 | 11.49 ± 2.96 | 8.40 ± 3.25 | 7.52 ± 3.95 | 6.95 ± 3.56 | 6.72 ± 3.55 |

| Ratio inner urban/suburban | 0.81 | 0.74 | 1.22 | 1.48 | 1.38 | 1.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andersson, D.; Wahlgren, L.; Schantz, P. Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Motorized Traffic in Suburban–Rural Areas of a Metropolitan Region: Exploring Measurement Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020206

Andersson D, Wahlgren L, Schantz P. Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Motorized Traffic in Suburban–Rural Areas of a Metropolitan Region: Exploring Measurement Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(2):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndersson, Dan, Lina Wahlgren, and Peter Schantz. 2026. "Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Motorized Traffic in Suburban–Rural Areas of a Metropolitan Region: Exploring Measurement Perspectives" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 2: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020206

APA StyleAndersson, D., Wahlgren, L., & Schantz, P. (2026). Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Motorized Traffic in Suburban–Rural Areas of a Metropolitan Region: Exploring Measurement Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(2), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020206