Challenges and Practices in Perishable Food Supply Chain Management in Remote Indigenous Communities: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework for Enhancing Food Access

Abstract

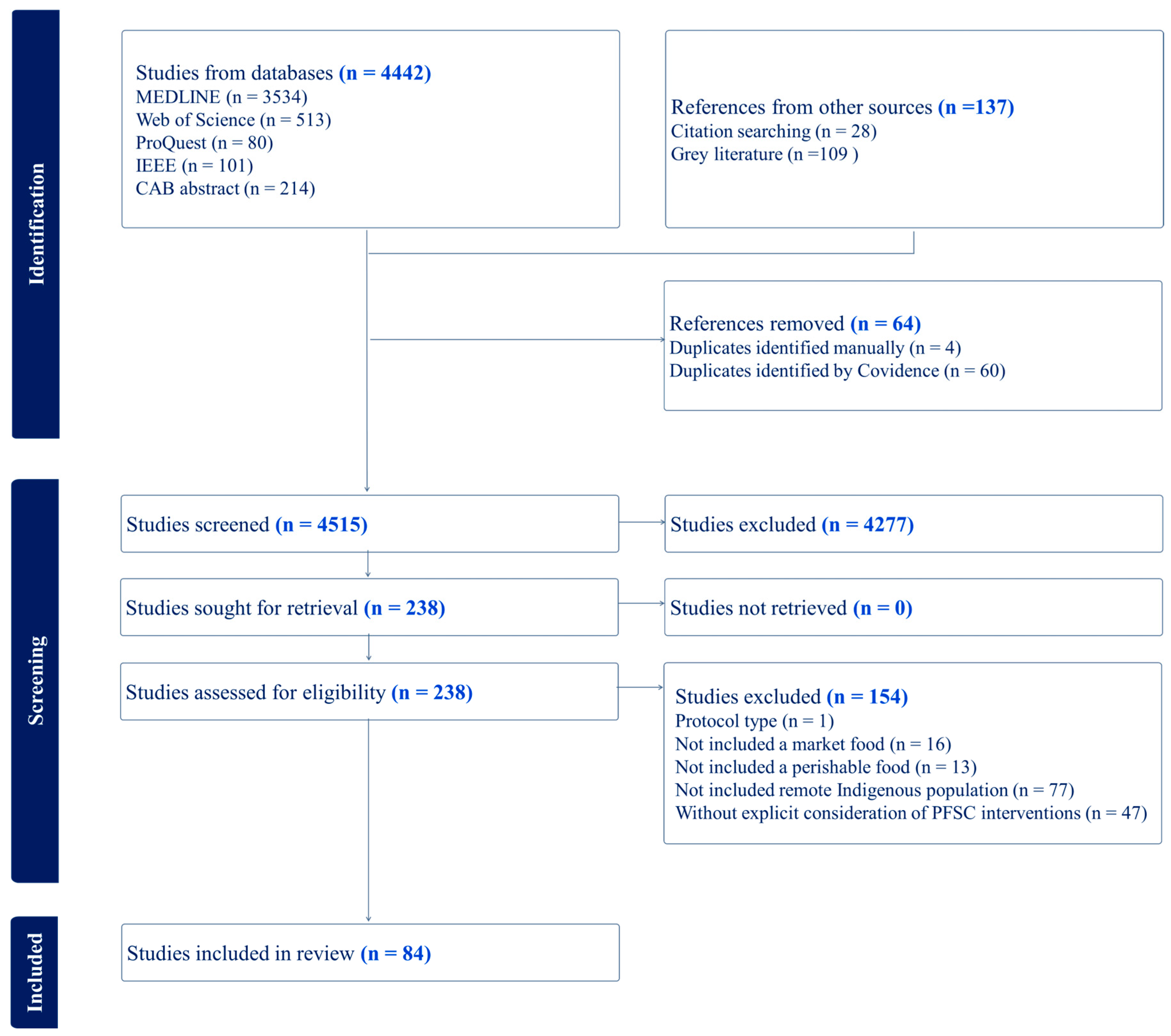

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- RQ1. What are the PFSCM challenges that affect food access components in remote Indigenous communities across global regions, and at which supply chain levels do these challenges occur?

- RQ2. What PFSCM practices have been implemented to address these challenges?

- RQ3. How can reported PFSCM challenges and practices be synthesized and organized into an integrative conceptual framework?

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of Included Sources

3.2. PFSCM Challenges in Remote Indigenous Communities

3.2.1. Local Production and External Supply Challenges

3.2.2. Distribution-Level Challenges

3.2.3. Retail-Level Challenges

3.2.4. Consumption-Level Challenges

3.3. PFSCM Practices in Remote Indigenous Communities

3.3.1. PFSC Redesigning Strategies

3.3.2. Forecasting and Optimization Models

3.3.3. Technology Approaches

3.3.4. Collaboration and Coordination Strategies

3.3.5. Investments

4. Discussion

5. Knowledge Gaps and Pathways for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFSC | Perishable food supply chain |

| PFSCM | Perishable food supply chain management |

| PCC | Population/Phenomenon, Concept, and Context |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| SCM | Supply Chain Management |

| FSC | Food Supply Chain |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| NNC | Nutrition North Canada |

| GST | Goods and Services Tax |

References

- World Bank. Indigenous Peoples Overview; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook; CIA: Langley, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, D. Australia’s Efforts to Improve Food Security for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 18, 209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fretts, A.M.; Huber, C.; Best, L.G.; O’Leary, M.; LeBeau, L.; Howard, B.V.; Siscovick, D.S.; Beresford, S.A. Availability and Cost of Healthy Foods in a Large American Indian Community in the North-Central United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, 170302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendimu, M.A.; Desmarais, A.A.; Martens, T.R. Access and Affordability of “Healthy” Foods in Northern Manitoba? The Need for Indigenous Food Sovereignty. Can. Food Stud. Rev. Can. Études Sur Aliment. 2018, 5, 44–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, K.; Lovato, V.; Nieto, T.; Neault, N.; Barlow, A.; Speakman, K. Increasing Healthy Food Availability, Purchasing, and Consumption: Lessons Learned from Implementing a Mobile Grocery. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2018, 12, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, R.; Huet, C.; Wood, M.; Lennie, C.; Osborne, G.; Egeland, G.M. Prevalence of Affirmative Responses to Questions of Food Insecurity: International Polar Year Inuit Health Survey, 2007–2008. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 2011, 70, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, C.; Rosol, R.; Egeland, G.M. The Prevalence of Food Insecurity Is High and the Diet Quality Poor in Inuit Communities3. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.M.; Nyaradi, A.; Lester, M.; Sauer, K. Understanding Food Security Issues in Remote Western Australian Indigenous Communities. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2014, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowerwine, J.; Mucioki, M.; Sarna-Wojcicki, D.; Hillman, L. Reframing Food Security by and for Native American Communities: A Case Study among Tribes in the Klamath River Basin of Oregon and California. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 579–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge; Council of Canadian Academies: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta-Cortijo, C.; Ford, J.D.; Arotoma-Rojas, I.; Lwasa, S.; Lancha-Rucoba, G.; García, P.J.; Miranda, J.J.; Namanya, D.B.; New, M.; Wright, C.J.; et al. Climate Change and COVID-19: Reinforcing Indigenous Food Systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e381–e382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, A.; Carter, B.; Blay-Palmer, A. Climate Change, Community Capitals, and Food Security: Building a More Sustainable Food System in a Northern Canadian Boreal Community. Can. Food Stud. Rev. Can. Études Sur Aliment. 2018, 5, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Remote Logistics: Exploring New Ways to Reduce Food Insecurity in Northern Canada. Master’s Thesis, University of Quebec in Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.M.; Koven, C.D.; Swenson, S.C.; Riley, W.J.; Slater, A.G. Permafrost Thaw and Resulting Soil Moisture Changes Regulate Projected High-Latitude CO2 and CH4 Emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, E.; Parisien, M.; Thompson, D.K.; Hall, R.J.; Skakun, R.S.; Flannigan, M.D. Variability and Drivers of Burn Severity in the Northwestern Canadian Boreal Forest. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiassat, A.; Diabat, A.; Rahwan, I. A Genetic Algorithm Approach for Location-Inventory-Routing Problem with Perishable Products. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 42, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltch, E.M.; Shin, S.S.; Houser, R.F.; Griffin, T. The Complexities of Selling Fruits and Vegetables in Remote Navajo Nation Retail Outlets: Perspectives from Owners and Managers of Small Stores. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biza, A.; Montastruc, L.; Negny, S.; Admassu, S. Strategic and Tactical Planning Model for the Design of Perishable Product Supply Chain Network in Ethiopia. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 190, 108814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Peterson, L.; Lieske, S.; Underhill, S.J.R.; Keys, N. Food Security, Remoteness and Consolidation of Supermarket Distribution Centres: Factors Contributing to Food Pricing Inequalities across Queensland, Australia. Aust. Geogr. 2016, 47, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, A.; Kenny, T.-A.; Harper, S.; Beale, D.; Premji, Z.; Furgal, C.; Ford, J.; Little, M. Inuit-Defined Determinants of Food Security in Academic Research Focusing on Inuit Nunangat and Alaska: A Scoping Review Protocol. Nutr. Health 2023, 29, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, T.-A.; Little, M.; Lemieux, T.; Griffin, P.J.; Wesche, S.D.; Ota, Y.; Batal, M.; Chan, H.M.; Lemire, M. The Retail Food Sector and Indigenous Peoples in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action: World Food Summit, 13–17 November 1996, Rome, Italy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, J.L.; Ruel, M.; Frongillo, E.A.; Harris, J.; Ballard, T.J. Measuring the Food Access Dimension of Food Security: A Critical Review and Mapping of Indicators. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36, 167–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, K.B.; Evenson, K.R. Obesity Prevalence and the Local Food Environment. Health Place 2009, 15, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Lenk, K.; Pelletier, J.E.; Barnes, T.L.; Harnack, L.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Association between Store Food Environment and Customer Purchases in Small Grocery Stores, Gas-Marts, Pharmacies and Dollar Stores. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Z.; Shanks, C.; Miles, M.; Rink, E. The Grocery Store Food Environment in Northern Greenland and Its Implications for the Health of Reproductive Age Women. J. Community Health 2018, 43, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasuk, V.; Mitchell, A.; Dachner, N. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2014; Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk, V.; Li, T.; St-Germain, A.-A.F. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021; Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, J.; Lock, M.; Walker, T.; Egan, M.; Backholer, K. Effects of Food Policy Actions on Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Herron, L.; Rainow, S.; Wells, L.; Kenny, I.; Kenny, L.; Wells, I.; Kavanagh, M.; Bryce, S.; Balmer, L. Improving Economic Access to Healthy Diets in First Nations Communities in High-Income, Colonised Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif, K.; Azima, S.; Doyon, M. Investigating Perishable Food Supply Chain Management Challenges in Remote Arctic Communities: Insights from an Embedded Case Study. Br. Food J. 2025, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of Small Farms and Innovative Food Supply Chains: The Role of Food Hubs in Creating Sustainable Regional and Local Food Systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M.; Bregoli, I. Sustainability in Alternative Food Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, H.; Connors, J.P.; Wharton, C.; Bertmann, F.; Xiong, A.; Stoltzfus, J. Identifying Attributes of Food System Sustainability: Emerging Themes and Consensus. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafi, A.; Zainuddin, N.B.; Mansor, M.F.; Bin Salleh, M.N.; Mohd Saifudin, A.B.; Azam Arif, N.; Aimi Shahron, S.; Ramasamy, R.; Hassan Mohamud, I. Navigating the Future of Agri-Food Supply Chain: A Conceptual Framework Using Bibliometric Review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, K.B.; Singhal, V.R. The Effect of Demand–Supply Mismatches on Firm Risk. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 2137–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugos, M.H. Essentials of Supply Chain Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Supply Chain Council (SCC). Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model; Supply Chain Council (SCC): Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo, G.; Skinner, K.; Phillipps, B.; Yu, Z.; Martin, D.; Mah, C.L. The Retail Food Environment, Store Foods, and Diet and Health among Indigenous Populations: A Scoping Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping Reviews: Reinforcing and Advancing the Methodology and Application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Hassanein, Z.M.; Bains, M.; Bennett, C.; Bjerrum, M.; Edgley, A.; Edwards, D.; Porritt, K.; Salmond, S. Addressing Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in JBI Qualitative Systematic Reviews: A Methodological Scoping Review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2025, 23, 454–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; the PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J. In No Uncertain Terms: The Importance of a Defined Objective in Scoping Reviews. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda Rianos, C.K.; Torres, C.A.; Zapata Calero, J.C.; Romero-Leiton, J.P.; Benavides, I.F. A Machine Learning Approach to Map the Potential Agroecological Complexity in an Indigenous Community of Colombia. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Orozco, H.; Meléndez-Bermúdez, O.; Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Morillo, D.; Rey, C.; Gatica, G. The Organization of Fruit Collection Transport in Conditions of Extreme Rurality: A Rural CVRP Case. In Applied Computer Sciences in Engineering; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Figueroa-García, J.C., Franco, C., Díaz-Gutierrez, Y., Hernández-Pérez, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1685, pp. 234–242. ISBN 978-3-031-20610-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, M.; Lane, G.; Szafron, M.; Hillier, K.; Pahwa, P.; Vatanparast, H. Exploring the Implications of COVID-19 on Food Security and Coping Strategies among Urban Indigenous Peoples in Saskatchewan, Canada. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Macdonald, J.P.; Huet, C.; Statham, S.; MacRury, A. Food Policy in the Canadian North: Is There a Role for Country Food Markets? Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 152, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, C.; Dehghani-Sanij, A.; Mahbaz, S.; Dusseault, M.; Nathwani, J.; Fraser, R. Geothermal Energy for Sustainable Food Production in Canada’s Remote Northern Communities. Energies 2019, 12, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamalice, A.; Avard, E.; Coxam, V.; Herrmann, T.; Desbiens, C.; Wittrant, Y.; Blangy, S. Supporting Food Security in the Far North: Community Greenhouse Projects in Nunavik and Nunavut. Etudes Inuit Stud. 2016, 40, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamalice, A.; Haillot, D.; Lamontagne, M.; Herrmann, T.; Gibout, S.; Blangy, S.; Martin, J.; Coxam, V.; Arsenault, J.; Munro, L.; et al. Building Food Security in the Canadian Arctic through the Development of Sustainable Community Greenhouses and Gardening. Ecoscience 2018, 25, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, E.; Ross, C.T.; Beheim, B.; Parrott, J. Indigenous Food Production in a Carbon Economy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2317686121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.M.; Desjardins, E.; Tsuji, L.J.S. Giving Voice to Food Insecurity in a Remote Indigenous Community in Subarctic Ontario, Canada: Traditional Ways, Ways to Cope, Ways Forward. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Minard, S.; Edens, C. Local Foods and Low-Income Communities: Location, Transportation, and Values. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, S.C.; Loring, P.A. Rebuilding Northern Foodsheds, Sustainable Food Systems, Community Well-Being, and Food Security. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 2013, 72, 21560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Lastimosa, I.; Chung-Do, J.J.; Hwang, P.W.; Radovich, T.; Rogerson, I.; Ho, K.; Keaulana, S.; Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, J.; Spencer, M.S. Integrating Native Hawaiian Tradition with the Modern Technology of Aquaponics. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, A.; O’Dea, K.; Brimblecombe, J. “We Need Our Own Food, to Grow Our Own Veggies…” Remote Aboriginal Food Gardens in the Top End of Australia’s Northern Territory. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2013, 37, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiq, F.F.; Coles, D.; Hubbard, C.; Clark, B.; Frewer, L.J. Factors Influencing Consumption of Traditional Diets: Stakeholder Views Regarding Sago Consumption among the Indigenous Peoples of West Papua. Agric. Food Secur. 2022, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.M.; Kapoor, R.; Merchant, E.V.; Sullivan, T.; Singh, G.; Fanzo, J.; Ghosh-Jerath, S. Leveraging Nutrient-Rich Traditional Foods to Improve Diets among Indigenous Populations in India: Value Chain Analysis of Finger Millet and Kionaar Leaves. Foods 2022, 11, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.; Fox, E.; Mutuku, V.; Muindi, Z.; Fatima, T.; Pavlovic, I.; Husain, S.; Sabbahi, M.; Kimenju, S.; Ahmed, S. Food Environments and Their Influence on Food Choices: A Case Study in Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogo, E.; Opiyo, A.; Ulrichs, C.; Huyskens-Keil, S. Nutritional and Economic Postharvest Loss Analysis of African Indigenous Leafy Vegetables along the Supply Chain in Kenya. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 130, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.R.; Ferreira, A.A.; Souza, M.C.D.; Coimbra, C.E.A.J. Food Profiles of Indigenous Households in Brazil: Results of the First National Survey of Indigenous Peoples’ Health and Nutrition. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lewis, M. Testing the Price of Healthy and Current Diets in Remote Aboriginal Communities to Improve Food Security: Development of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthy Diets ASAP (Australian Standardised Affordability and Pricing) Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambden, J.; Receveur, O.; Marshall, J.; Kuhnlein, H.V. Traditional and Market Food Access in Arctic Canada Is Affected by Economic Factors. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 2006, 65, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, W.; Raj, A.; Reeve, E.; Guerrero, R.L.; Fesaitu, J.; Cateine, K.; Guignet, C. Processed Foods Available in the Pacific Islands. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.; Bancroft, C.; Salt, S.; Curley, C.; Curley, C.; de Heer, H.; Yazzie, D.; Eddie, R.; Antone-Nez, R.; Shin, S. Changes in Food Pricing and Availability on the Navajo Nation Following a 2% Tax on Unhealthy Foods: The Healthy Dine Nation Act of 2014. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelli, A.; Donovan, J.; Margolies, A.; Aberman, N.; Santacroce, M.; Chirwa, E.; Henson, S.; Hawkes, C. Value Chains to Improve Diets: Diagnostics to Support Intervention Design in Malawi. Glob. Food Secur.-Agric. Policy Econ. Environ. 2020, 25, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minier, L.; Fourrière, M.; Gairin, E.; Gourlaouen, A.; Krimou, S.; Berthe, C.; Maueau, T.; Doom, M.; Sturny, V.; Mills, S.; et al. Roadside Sales Activities in a South Pacific Island (Bora-Bora) Reveal Sustainable Strategies for Local Food Supply during a Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.; Lo, J.; Davies, C.; Darby, J.; Devine, A. Which Food Security Determinants Predict Adequate Vegetable Consumption among Rural Western Australian Children? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.M.; Fediuk, K.; Hamilton, S.; Rostas, L.; Caughey, A.; Kuhnlein, H.; Egeland, G.; Loring, E. Food Security in Nunavut, Canada: Barriers and Recommendations. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 2006, 65, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal, L.; Lanumata, T.; Robinson, J.-A.; Tavila, A.; Wilton, J.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Perceptions of New Zealand Nutrition Labels by Maori, Pacific and Low-Income Shoppers. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, F.H.; Godrich, S.L. Interventions to Address Food Insecurity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: A Rapid Review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Rainow, S.; Balmer, L.; Hutchinson, R.; Bryce, S.; Lewis, M.; Herron, L.-M.; Torzillo, P.; Stevens, R.; Kavanagh, M.; et al. Making It on the Breadline—Improving Food Security on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, Central Australia. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, E.; Gittelsohn, J.; Kratzmann, M.; Roache, C.; Sharma, S. Impact of the Changing Food Environment on Dietary Practices of an Inuit Population in Arctic Canada. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socha, T.; Chambers, L.; Zahaf, M.; Abraham, R. Food Availability, Food Store Management, and Food Pricing in a Northern First Nation Community. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, A.; Spiegel, J.; Guhn, M.; Wittman, H.; Ing, A.; Sadik, T.; Fediuk, K.; Tikhonov, C.; Schwartz, H.; Chan, H.M.; et al. Predictors of Household Food Insecurity and Relationship with Obesity in First Nations Communities in British Columbia, Manitoba, Alberta and Ontario. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayman, J.; Moore-Wilson, H.; Vavra, C.; Wormington, D.; Presley, J.; Jauregui-Dusseau, A.; Clyma, K.; Jernigan, V. The Center for Indigenous Innovation and Health Equity: The Osage Nation’s Mobile Market. Health Promot. Pract. 2023, 24, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.; Rich, K.; Shankar, B.; Rana, V. The Challenges of Aligning Aggregation Schemes with Equitable Fruit and Vegetable Delivery: Lessons from Bihar, India. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 12, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Beaumier, M. Feeding the Family during Times of Stress: Experience and Determinants of Food Insecurity in an Inuit Community. Geogr. J. 2011, 177, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, T. Is the Nutrition North Canada Retail Subsidy Program Meeting the Goal of Making Nutritious and Perishable Food More Accessible and Affordable in the North? Can. J. Public Health-Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2014, 105, E395–E397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, K.R.; Flanagan, C.A.; Nu, J.; Lee, F.R.; Desnoyers, C.; Walch, A.; Alexie, L.; Bersamin, A.; Thomas, T.K. Storekeeper Perspectives on Improving Dietary Intake in 12 Rural Remote Western Alaska Communities: The “Got Neqpiaq?” Project. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 2021, 80, 1961393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Burgel, E.; Fairweather, M.; Hill, A.; Christian, M.; Ferguson, M.; Lee, A.; Funston, S.; Fredericks, B.; McMahon, E.; Pollard, C.; et al. Development of a Survey Tool to Assess the Environmental Determinants of Health-Enabling Food Retail Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities of Remote Australia. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Position, É.N. Addressing Household Food Insecurity in Canada—Position Statement and Recommendations—Dietitians of Canada. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2016, 77, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Patay, D.; Herron, L.-M.; Parnell Harrison, E.; Lewis, M. Affordability of Current, and Healthy, More Equitable, Sustainable Diets by Area of Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Remoteness in Queensland: Insights into Food Choice. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, K.; Skinner, K.; Hay, T.; LeBlanc, J.; Chambers, L. Retail Food Environments, Shopping Experiences, First Nations and the Provincial Norths. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 37, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, M.L. Looking to the Land: Local Responses to Food Insecurity in Two Rural and Remote First Nations. Can. J. Native Stud. 2018, 38, 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Block, D.; Kouba, J. A Comparison of the Availability and Affordability of a Market Basket in Two Communities in the Chicago Area. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodor, J.; Rice, J.; Farley, T.; Swalm, C.; Rose, D. Disparities in Food Access: Does Aggregate Availability of Key Foods from Other Stores Offset the Relative Lack of Supermarkets in African-American Neighborhoods? Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeen, E.A.; VanFrank, B.K.; Jackson, S.L.; Harmon, B.; Uncangco, A.; Luces, P.; Dooyema, C.; Park, S. Availability and Promotion of Healthful Foods in Stores and Restaurants—Guam, 2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, 160528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, O.; George, C.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Lasky-Fink, J.; Piltch, E.; Sandman, S.; Clark, C.; Avalos, Q.; Carroll, D.; Wilmot, T.; et al. Healthy Stores Initiative Associated with Produce Purchasing on Navajo Nation. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.; Deen, C.; Thompson, K.; Kleve, S.; Chan, E.; McCarthy, L.; Kraft, E.; Fredericks, B.; Brimblecombe, J.; Ferguson, M. Conceptualisation, Experiences and Suggestions for Improvement of Food Security amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Parents and Carers in Remote Australian Communities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 320, 115726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Laws, C.; Leonard, D.; Campbell, S.; Merone, L.; Hammond, M.; Thompson, K.; Canuto, K.; Brimblecombe, J. Healthy Choice Rewards: A Feasibility Trial of Incentives to Influence Consumer Food Choices in a Remote Australian Aboriginal Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; O’Dea, K.; Chatfield, M.; Moodie, M.; Altman, J.; Brimblecombe, J. The Comparative Cost of Food and Beverages at Remote Indigenous Communities, Northern Territory, Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Bailie, R.; van den Boogaard, C.; Wood, B.; Liberato, S.C.; Ferguson, M.; Coveney, J.; Jaenke, R.; Ritchie, J. Feasibility of a Novel Participatory Multi-Sector Continuous Improvement Approach to Enhance Food Security in Remote Indigenous Australian Communities. SSM—Popul. Health 2017, 3, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.; O’Dea, K.; Holden, S.; Miles, E.; Brimblecombe, J. Food and Beverage Price Discounts to Improve Health in Remote Aboriginal Communities: Mixed Method Evaluation of a Natural Experiment. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.; O’Dea, K.; Altman, J.; Moodie, M.; Brimblecombe, J. Health-Promoting Food Pricing Policies and Decision-Making in Very Remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Stores in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Pathak, P.; Kumar, A.; Gautam, S. Sustainable Regenerative Agriculture Allied with Digital Agri-Technologies and Future Perspectives for Transforming Indian Agriculture. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 30409–30444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.S.; Singh, A.R.; Raut, R.D.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Exploring the Application of Industry 4.0 Technologies in the Agricultural Food Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, M.; Keshavarz, P.; Lane, G.; Pahwa, P.; Szafron, M.; Jennings, D.; Vatanparast, H. Food Security Status of Indigenous Peoples in Canada According to the 4 Pillars of Food Security: A Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 2537–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.R.; Coveney, J.; Verity, F.; Carter, P.; Schilling, M. Cost and Affordability of Healthy Food in Rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, V.B.B.; Williams, M.; Wetherill, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Jacob, T.; Cannady, T.; Grammar, M.; Standridge, J.; Fox, J.; Wiley, A.; et al. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Develop Healthy Retail Strategies in Native American-Owned Convenience Stores: The THRIVE Study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 11, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnus, A.; Moodie, M.L.; Ferguson, M.; Cobiac, L.J.; Liberato, S.C.; Brimblecombe, J. The Economic Feasibility of Price Discounts to Improve Diet in Australian Aboriginal Remote Communities. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, S36–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Miles, B.; Chappell, E.; De Silva, K.; Ferguson, M.; Mah, C.; Miles, E.; Gunther, A.; Wycherley, T.; Peeters, A.; et al. Implementation of a Food Retail Intervention to Reduce Purchase of Unhealthy Food and Beverages in Remote Australia: Mixed-Method Evaluation Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía, G.; Granados-Rivera, D.; Jarrín, J.A.; Castellanos, A.; Mayorquín, N.; Molano, E. Strategic Supply Chain Planning for Food Hubs in Central Colombia: An Approach for Sustainable Food Supply and Distribution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.; Dirks, N.; Walther, G. Improving Rural Accessibility by Locating Multimodal Mobility Hubs. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 94, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.-S.; Song, P.-C.; Chu, S.-C.; Peng, Y.-J. Improved Compact Cuckoo Search Algorithm Applied to Location of Drone Logistics Hub. Mathematics 2020, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommens, K.; Buldeo Rai, H.; Van Lier, T.; Macharis, C. Delivery to Homes or Collection Points? A Sustainability Analysis for Urban, Urbanised and Rural Areas in Belgium. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 94, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, I.; Fernández, E. General Network Design: A Unified View of Combined Location and Network Design Problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 680–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Batta, R.; Rogerson, P.A.; Blatt, A.; Flanigan, M. Location of Temporary Depots to Facilitate Relief Operations after an Earthquake. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2012, 46, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano Macias, J.; Angeloudis, P.; Ochieng, W. Optimal Hub Selection for Rapid Medical Deliveries Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 110, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, D.; Wu, L. Optimizing Locations of Waste Transfer Stations in Rural Areas. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, J.K.; Benta, A.; Lopes, R.B.; Lopes, N. A Multi-Objective Analysis of a Rural Road Network Problem in the Hilly Regions of Nepal. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2014, 64, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.B.; Sengul, I.; Ivy, J.S.; Brock, L.G.; Miles, L. Scheduling Food Bank Collections and Deliveries to Ensure Food Safety and Improve Access. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2014, 48, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmadhikari, N.; Farahmand, K. Location Allocation of Sugar Beet Piling Centers Using GIS and Optimization. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țîțu, M.; Oprean, C.; Pîrnau, C.; Țîțu, Ș. Using the Modelling and Simulation Techniques to Improve the Management of SMEs Belonging to Regional Clusters. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 7, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockshell, J.; Nielsen Ritter, T. Applying the Six-Dimensional Food Security Framework to Examine a Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program Implemented by Self-Help Groups during the COVID-19 Lockdown in India. World Dev. 2024, 175, 106486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Food Policy Research Institute. Food Systems; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, S.K.; van Burgel, E.; Cubillo, B.; Connally, S.; Ferguson, M.; Brimblecombe, J. Stores Licensing Scheme in Remote Indigenous Communities of the Northern Territory, Australia: A Meta-Evaluation. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blay-Palmer, A.; Landman, K.; Knezevic, I.; Hayhurst, R. Constructing Resilient, Transformative Communities through Sustainable “Food Hubs”. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, E.R. Synergies in Alternative Food Network Research: Embodiment, Diverse Economies, and More-than-Human Food Geographies. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Horizontal Evaluation of Nutrition North Canada; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Audit Office. Food Security in Remote Indigenous Communities; Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Ferguson, M.; Chatfield, M.D.; Liberato, S.C.; Gunther, A.; Ball, K.; Moodie, M.; Miles, E.; Magnus, A.; Mhurchu, C.N.; et al. Effect of a Price Discount and Consumer Education Strategy on Food and Beverage Purchases in Remote Indigenous Australia: A Stepped-Wedge Randomized Controlled Trial. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e82–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Kamal, A.G.; Alam, M.A.; Wiebe, J. Community Development to Feed the Family in Northern Manitoba Communities: Evaluating Food Activities Based on Their Food Sovereignty, Food Security, and Sustainable Livelihood Outcomes. Can. J. Nonprofit Soc. Econ. Res. 2012, 3, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.K.; Keramydas, C.A.; Toka, A.K.; Aidonis, D.A.; Iakovou, E.T. Agrifood Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Hierarchical Decision-Making Framework and a Critical Taxonomy. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 120, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, B.M.; Achsan, R.E.D.; Asih, A.M.S. Mount Merapi Eruption: Simulating Dynamic Evacuation and Volunteer Coordination Using Agent-Based Modeling Approach. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 9, 292–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natcher, D.C. Social Capital and the Vulnerability of Aboriginal Food Systems in Canada. Hum. Organ. 2015, 74, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natcher, D.C. Subsistence and the Social Economy of Canada’s Aboriginal North. North. Rev. 2009, 30, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Spring, C.; Temmer, J.; Skinner, K.; Simba, M.; Chicot, L.; Spring, A. Proposing Dimensions of an Agroecological Fishery: The Case of a Small-Scale Indigenous-Led Fishery Within Northwest Territories, Canada. Conservation 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, E. Sharing-Based Social Capital Associated with Harvest Production and Wealth in the Canadian Arctic. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandekar, S.R.; Vijayalakshmi, C. Optimization Algorithm in Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 5072–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, P.; Land, A.; Seuring, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices and Dynamic Capabilities in the Food Industry: A Critical Analysis of the Literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Naim, I.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Gupta, H.; Idrisi, A.R. A Knowledge-Based Experts’ System for Evaluation of Digital Supply Chain Readiness. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 228, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Morgan, V.S.; Lamb, C. “I Spent the First Year Drinking Tea”: Exploring Canadian University Researchers’ Perspectives on Community-based Participatory Research Involving Indigenous Peoples. Can. Geogr. Géographies Can. 2012, 56, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matopoulos, A.; Vlachopoulou, M.; Manthou, V.; Manos, B. A Conceptual Framework for Supply Chain Collaboration: Empirical Evidence from the Agri-food Industry. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddh, M.M.; Soni, G.; Jain, R.; Sharma, M.K.; Yadav, V. Agri-Fresh Food Supply Chain Quality (AFSCQ): A Literature Review. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 2015–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamud, I.H.; Kafi, M.A.; Shahron, S.A.; Zainuddin, N.; Musa, S. The Role of Warehouse Layout and Operations in Warehouse Efficiency: A Literature Review. J. Eur. Systèmes Autom. 2023, 56, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Lopez, C.; Chen, H.; Lu, H.; Mangla, S.K.; Elgueta, S. Risk Analysis of the Agri-Food Supply Chain: A Multi-Method Approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4851–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.; Brochado, A.; Marques, R.C. Public-Private Partnerships in the Water Sector: A Review. Util. Policy 2021, 69, 101182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obonyo, E.; Formentini, M.; Ndiritu, S.W.; Naslund, D. Information Sharing in African Perishable Agri-Food Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 15, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.N.; Wolfert, J.; Beulens, A.J.M.; Rialland, A. Virtualization of Food Supply Chains with the Internet of Things. J. Food Eng. 2016, 176, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhao, Q.; An, Z.; Tang, O. Collaborative Mechanism of a Sustainable Supply Chain with Environmental Constraints and Carbon Caps. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Daya, M.; Hassini, E.; Bahroun, Z. Internet of Things and Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4719–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodan, R.; Rashed, M.S.; Pandit, M.K.; Parmar, P.; Pathania, S. Internet of Things in Food Industry. In Innovation Strategies in the Food Industry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 287–303. ISBN 978-0-323-85203-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzembrak, Y.; Klüche, M.; Gavai, A.; Marvin, H.J.P. Internet of Things in Food Safety: Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Siddik, A.; Pertheban, T.; Rahmand, M. Does Fintech Innovation and Green Transformational Leadership Improve Green Innovation and Corporate Environmental Performance? A Hybrid SEM-ANN Approach. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Croxton, K.L.; Fiksel, J. Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development and Implementation of an Assessment Tool. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Brewster, C.; Spek, J.; Smeenk, A.; Top, J.; Van Diepen, F.; Klaase, B.; Graumans, C.; De Ruyter De Wildt, M. Blockchain for Agriculture and Food: Findings from the Pilot Study; Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benos, L.; Moysiadis, V.; Kateris, D.; Tagarakis, A.C.; Busato, P.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Human–Robot Interaction in Agriculture: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Wang, J.C.-H. Food Budget Ratio as an Equitable Metric for Food Affordability and Insecurity: A Population-Based Cohort Study of 121 Remote Indigenous Communities in Canada. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziso, D.; Chun, O.; Puglisi, M. Increasing Access to Healthy Foods through Improving Food Environment: A Review of Mixed Methods Intervention Studies with Residents of Low-Income Communities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Aydın, N.S.; Ranjbar-Bourani, M.; Weber, G.-W. A Robust Bi-Objective Mathematical Model for Disaster Rescue Units Allocation and Scheduling with Learning Effect. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distribution-Related Challenges | Context | Food Access Components | Sources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Affordability | Cultural Acceptability | Variety | Quality | |||

| Long-distance transport | Canada (BC, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario), Australia, Greenland | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | [9,21,53,58,74,81,84] |

| No year-round road access | Canada (subarctic Ontario), Australia, Greenland | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | [5,28,58,78,85] |

| Centralized distribution hubs | Rural Queensland (Australia) | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | [21] |

| Multi-stop air deliveries | Remote Alaska, Canada (Inuit communities) | × | × | × | × | ✓ | [75,86] |

| Unpredictable weather | Canada (Arctic), Australia (Northern Territory), Greenland | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | [9,28,79,86] |

| High fuel costs | Northern Canada (Manitoba), Alaska, Australia | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | [5,87] |

| Unflexible transportation mode | Remote communities in Western Australia, Remote Inuit communities, and communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Region of rural Alaska | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | [9,79,86,87] |

| Lack of cold chain infrastructure | Australia (Aboriginal communities), Northern Canada | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | [13,33,77,87] |

| Vendor minimum orders | Navajo Nation (USA), Alaska | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | [19,86] |

| Infrequent deliveries | Greenland, Alaska, Canada | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | [9,28] |

| Challenges | Context | Food Access Components | Sources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Affordability | Cultural Acceptability | Variety | Quality | |||

| Limited competition in retail food markets | Remote Indigenous areas of Canada (e.g., Wapekeka in Ontario) and Western Australia | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | [5,9,33,74,90,91] |

| Store type and food access | Subarctic Ontario (Canada), Gitxaala (British Columbia, Canada), Navajo Nation, Guam, India | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [58,65,91,94,95] |

| Inadequate store infrastructure | Canada and Australia | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ | [9,79,87,96,97] |

| Fluctuating prices | Australia and Greenland | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | [28,100,101] |

| Demand-supply mismatches | Arctic Canada, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander communities (Australia) | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | [9,78,87,90] |

| PFSC Redesign Strategies | Context | Food Access Components | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community-based solutions | Subarctic Ontario, Nunavik, Nunavut, Saskatchewan, Alaska | Cultural acceptability, availability, affordability, and variety | [52,55,58,60] |

| Multi-echelon distribution hubs | Remote rural areas of Canada | Accessibility, affordability | [109,110] |

| Drone logistics hubs | Remote rural regions of Canada | Accessibility | [111] |

| Decentralized delivery systems | U.S. Indigenous communities, rural French Polynesia | Accessibility, cultural acceptability | [59,73,82] |

| Proximity-based retail models | Urban Indigenous communities, remote Australia | Accessibility, affordability | [9,59] |

| Author | Deterministic/Stochastic | Decision | What Is Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| [117] | Deterministic | Road upgrade | Coverage/costs |

| [109] | Deterministic | Hub allocation | Profits |

| [111] | Deterministic | Hub allocation | Distance |

| [120] | Deterministic | Food logistics components (collection, sorting, baling) | Not specified |

| [119] | Deterministic | Pilers | Cost |

| [110] | Deterministic | Hub allocation | Accessibility |

| [118] | Deterministic | Location-allocation-routing for food banks | Food access |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gharakhani Dehsorkhi, B.; Afif, K.; Doyon, M. Challenges and Practices in Perishable Food Supply Chain Management in Remote Indigenous Communities: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework for Enhancing Food Access. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010118

Gharakhani Dehsorkhi B, Afif K, Doyon M. Challenges and Practices in Perishable Food Supply Chain Management in Remote Indigenous Communities: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework for Enhancing Food Access. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleGharakhani Dehsorkhi, Behnaz, Karima Afif, and Maurice Doyon. 2026. "Challenges and Practices in Perishable Food Supply Chain Management in Remote Indigenous Communities: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework for Enhancing Food Access" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010118

APA StyleGharakhani Dehsorkhi, B., Afif, K., & Doyon, M. (2026). Challenges and Practices in Perishable Food Supply Chain Management in Remote Indigenous Communities: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework for Enhancing Food Access. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010118