Bridging the Gap: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a New Rural Maternity Care Center Amid Nationwide Closures

Highlights

- Rural maternity unit closures exacerbate geographic and racial/ethnic inequities in maternal and neonatal health outcomes; this study examines the impact of restoring local access to maternity care.

- By evaluating both clinical outcomes and patient experiences after the reopening of a rural maternity care center, this work addresses a critical gap in understanding how service restoration affects access, quality, and patient-centered care.

- Findings demonstrate that reopening a rural Level I Maternity Care Center can maintain safe and comparable labor and delivery outcomes while reducing travel burden by half, thereby improving access to timely, equitable perinatal care.

- The study highlights a resource-appropriate maternity care unit of family physicians and midwives that provides a model for delivering quality rural maternity services in underserved regions nationally.

- Researchers and practitioners should explore scalable, multidisciplinary staffing models and community-informed implementation strategies to expand high-quality rural perinatal care where maternity care services have been lost.

- To sustain rural maternity care, health systems and policymakers must invest resources to increase reimbursement for these services, incentivize practice in rural areas, and ensure ongoing training and interprofessional development for rural maternity and newborn teams.

Abstract

1. Introduction

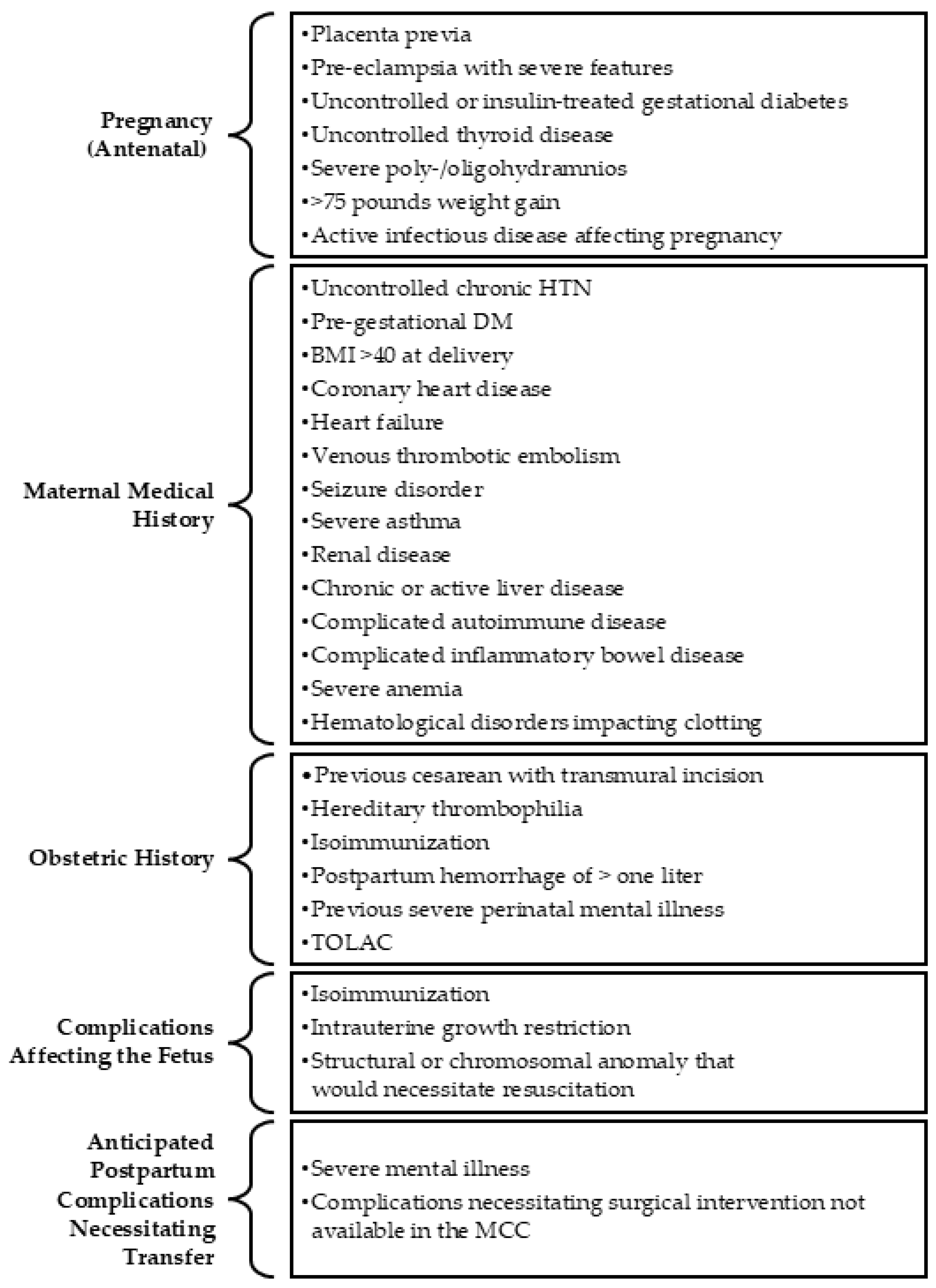

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Design

2.2. Quantitative Data Collection

2.3. Qualitative Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.1.1. Descriptive Characteristics

3.1.2. Labor and Delivery Outcomes

3.1.3. Distance to Care

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Descriptive Characteristics

3.2.2. Thematic Findings

“So, my husband and I spoke and one of the advantages that we looked at the most was that it was here near the house and since we have two; I have a little girl of seven years old. He told me, we are close, I can come and go from the hospital to see the girl. And that was also what motivated us the most in the child being born here.”

“I was more than happy…I bragged about it. A lot of people give like a bad rep…you know how they do little bitty hospitals, they think they’re the worst when sometimes they’re not… I didn’t tell many people that I was actually giving birth in [name of rural town], because of the way people think about it, they would be like, ‘why would you do that?’ …And [since the birth] I’ve actually told another girl—I was like, hey, have your baby there, and she had an amazing experience too. And everybody that went after me, I was like, well I had my baby there, great experience.”

3.3. Integration and Triangulation of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| IUFD | Intrauterine Fetal Demise |

| MCC | Maternity Care Center |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| SMFM | Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine |

| TOLAC | Trial of labor after cesarean |

Appendix A

| Qualitative Data | Themes | Convergent Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|

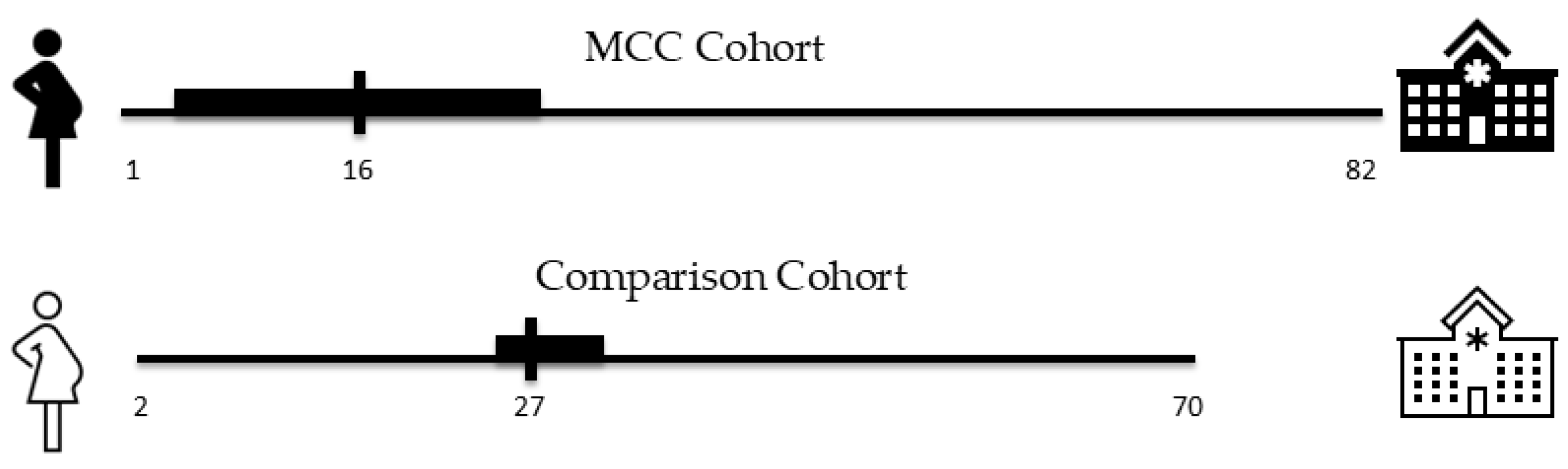

| “I had my baby within 15 min of arriving at the hospital. So, I think that if [the MCC] had not been there, I would have had my baby in a car.” “I did not want to consider traveling the 45 min it normally took me to get to the other location.” “I have a child that suffers from [medical condition], and I didn’t want to go very far to the other hospital…That was the most important thing, to not go so far away because of my son.” “So, my husband and I spoke and one of the advantages that we looked at the most was that it was here near the house and since we have two; I have a little girl of seven years old. He told me, we are close, I can come and go from the hospital to see the girl. And that was also what motivated us the most in the child being born here.” “And, yeah, since my pregnancy wasn’t a high risk, you know, I would just go to a closer place to where I live.” “It was really close to my house and we were able to get there like fairly quick.” “She asked me which hospital I preferred and I told her the closest one.” | Distance to care | 32% of MCC patients lived 5 or fewer miles from the hospital, while less than 1% of patients resided 5 or fewer miles from the tertiary care hospital. The median distance to care was 16 miles for the MCC cohort and 27 miles for the comparison cohort who delivered at the tertiary care hospital. |

| “I’d seen [doctor’s name] the whole time I was there. I mean, usually you see the doctor one time, and you never see him again.” “I would say, the lady, the person who helped me deliver—I wish I knew her title, I want to call her midwife, but she may not even be a midwife—but she was very encouraging.” “She immediately ran to get the doctor that helped me deliver my baby. She immediately went and it wasn’t even like the doctor that was there. I think it was a midwife. She immediately went to get her. And I had my baby like five minutes later…But the lady, the midwife that helped me deliver, was very, very good. And I just remember thanking the nurse for for only having to tell her once that I, that this is what I’m feeling, like I can feel him coming. And she immediately responded. She didn’t say, Mom, don’t push, or nothing. She just went ahead, and you know, I felt heard. That’s what I told them after giving birth.” “Like I couldn’t have had a better support system there with the nurses and the doctor and the midwives, even from whenever I, before I called and went in, I called and the midwife talked to me and she coached me while I was at home.” “I mean, anything to do to help [the MCC] for their maternity ward, I would do it, just so they can end up getting the NICU for mothers like me who need it.” “I really don’t have any complaints. In the future, I would like to see them have a NICU, just in case. But other than that, they were wonderful.” | Provider model and hospital care environment | Deliveries at the MCC were significantly more likely to be attended by a family medicine physician (68.1%) or certified nurse-midwife (30.4%) compared to those at the tertiary care hospital. Infants at the tertiary care hospital were significantly more likely to experience a NICU stay after delivery (33.6%) compared with infants at the MCC (2.5%) who were transferred as necessary to the closest NICU (p < 0.0001) shortly after birth. |

| “Yeah, everything went as planned because I was able to deliver him vaginally. That’s what I’ve always wanted with my pregnancies. And I think they really basically let me do it, let me handle it by myself. And that’s what I wanted.” “They were very like, whatever you want—if you want medicine, that’s fine, if you don’t, then that’s fine, too. We’ll talk you through all of it. Never pushy on either one, which was fantastic because sometimes I felt that way at the other place.” “And they never, they never really asked about medicine. My husband would say, hey, like if she wanted to get that epidural now could she? And they were like, absolutely, she just needs to tell us.” “Well, I was in a little pain that day, but the girl was already 6 cm dilated and there they asked me if I wanted something for the pain. But I didn’t. I didn’t choose anything because a lot of people tell me it’s bad to choose it, something they give you so it doesn’t hurt. I preferred to have it that way, natural.” “There was no pain management or anything provided for me.” | Patient agency/Decision-making | 86.7% of patients at the MCC had vaginal deliveries compared to 84.7% of patients in the comparison cohort who delivered at the tertiary care hospital. 57.1% of patients at the MCC who had vaginal deliveries used an epidural, compared to 59.4% of patients who delivered vaginally at the tertiary care hospital. |

| “And it was… I didn’t, you know, I expected maybe less? But it was like a really nice place to give birth in.” “Prior, this is going to sound bad—but it’s in [name of rural town], and I guess I just didn’t think it was going to be wonderful. But when I took my tour, it definitely changed my mind. It was beautiful inside. It was very clean, very well maintained, all the workers were wonderful, very friendly, very personable, and through my birthing experience and afterward they were amazing.” “[The MCC] was just not anything of like the negative things that I have heard.” “I was more than happy…I bragged about it. A lot of people give like a bad rep…you know how they do little bitty hospitals, they think they’re the worst when sometimes they’re not… I didn’t tell many people that I was actually giving birth in [name of rural town], because of the way people think about it, they would be like, ‘why would you do that?’ …And [since the birth] I’ve actually told another girl—I was like, hey, have your baby there, and she had an amazing experience too. And everybody that went after me, I was like, well I had my baby there, great experience.” “…yeah, that hospital, it needs to stay open for women that are low risk, because not a lot of people get treated that well after having a baby. You just feel like a number. So, it’s an amazing hospital.” | Perception changes and recommendations | N/A—no relevant quantitative data was collected on this theme. |

References

- Stewart, S.D.; Henderson, Z. Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S. 2022 Report; March of Dimes: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D.; Tuttle, M.K.; Henning-Smith, C. Changes in hospital-based obstetric services in rural US counties, 2014–2018. JAMA 2020, 324, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D.; Carroll, C.; Sheffield, E.C.; Fritz, A.H.; McGregor, A.J.; Handley, S.C. Obstetric Care Access at Rural and Urban Hospitals in the United States. JAMA 2025, 333, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D.; Carroll, C.; Sheffield, E.C.; Fritz, A.H.; McGregor, A.J.; Handley, S.C. Obstetric Care Access Declined In Rural And Urban Hospitals Across US States, 2010–2022. Health Aff. 2025, 44, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D.; Admon, L.K.; Basile Ibrahim, B.L. Rural Hospital Administrators’ Beliefs About Safety, Financial Viability, and Community Need for Offering Obstetric Care. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e220204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.; Kozhimannil, K.B.; Casey, M.M.; Moscovice, I.S. Why are obstetric units in rural hospitals closing their doors? Health Serv. Res. 2016, 51, 1546–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Hung, P.; Prasad, S.; Casey, M.; Moscovice, I. Rural-urban differences in obstetric care, 2002–2010, and implications for the future. Med. Care 2014, 52, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CMS. Improving Access to Maternal Health Care in Rural Communities: Issue Brief; Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS): Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, B.A.; McCook, J.G.; Chaires, C. Burden of elective early-term births in rural Appalachia. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Driscoll, A.K. Births: Final Data for 2018. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2019, 68, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter, M.; Klein, S. Restoring Access to Maternity Care in Rural America. Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/sep/restoring-access-maternity-care-rural-america (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Hung, P.; Henning-Smith, C.; Casey, M.M.; Prasad, S. Association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and birth outcomes in rural counties in the United States. JAMA 2018, 319, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisonkova, S.; Haslam, M.D.; Dahlgren, L.; Chen, I.; Synnes, A.R.; Lim, K.I. Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among women in rural versus urban areas. CMAJ 2016, 188, E456–E465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, S.A.; Srinivas, S.K.; Ahlberg, C.; Small, D.S. The impact of obstetric unit closures on maternal and infant pregnancy outcomes. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Disparities in Rural Women. Committee Opinion No. 586. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/02/health-disparities-in-rural-women (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Admon, L.K.; Daw, J.R.; Interrante, J.D.; Ibrahim, B.B.; Millette, M.J.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Rural and Urban Differences in Insurance Coverage at Prepregnancy, Birth, and Postpartum. Obs. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Sheffield, E.C.; Fritz, A.H.; Henning-Smith, C.; Interrante, J.D.; Lewis, V.A. Rural/urban differences in rates and predictors of intimate partner violence and abuse screening among pregnant and postpartum United States residents. Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Casey, M.M.; Hung, P.; Prasad, S.; Moscovice, I.S. Location of childbirth for rural women: Implications for maternal levels of care. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 661.e1–661.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, J. Rural Hospital Closures: Number and Characteristics of Affected Hospitals and Contributing Factors. 2018. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-634 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Valencia, Z.; Sen, A.; Kurowski, D.; Martin, K.; Bozzi, D. Average Payments for Childbirth Among the Commercially Insured and Fee-for-Service Medicaid. Available online: https://healthcostinstitute.org/all-hcci-reports/average-payments-for-childbirth-among-the-commercially-insured-and-fee-for-service-medicaid/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Woodward, R.; Mazure, E.S.; Belden, C.M.; Denslow, S.; Fromewick, J.; Dixon, S.; Gist, W.; Sullivan, M.H. Association of prenatal stress with distance to delivery for pregnant women in Western North Carolina. Midwifery 2023, 118, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Access Hospitals. Available online: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/critical-access-hospitals?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Curry, L.; Nunez-Smith, M. Mixed Methods in Health Sciences Research: A Practical Primer; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.R.; Hollins Martin, C.; Redshaw, M. The Birth Satisfaction Scale-Revised Indicator (BSS-RI). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonix Transcription Software, v1; Sonix, Inc.: West Springfield, VA, USA, 2025.

- Rampin, R.; Rampin, V. Taguette: Open-source qualitative data analysis. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee Opinion No. 644: The Apgar Score. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/10/the-apgar-score (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Tong, S.T.; Morgan, Z.J.; Bazemore, A.W.; Eden, A.R.; Peterson, L.E. Maternity Access in Rural America: The Role of Family Physicians in Providing Access to Cesarean Sections. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2023, 36, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollowell, J.; Li, Y.; Bunch, K.; Brocklehurst, P. A comparison of intrapartum interventions and adverse outcomes by parity in planned freestanding midwifery unit and alongside midwifery unit births: Secondary analysis of ‘low risk’ births in the birthplace in England cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iobst, S.E.; Storr, C.L.; Bingham, D.; Zhu, S.; Johantgen, M. Variation of intrapartum care and cesarean rates among practitioners attending births of low-risk, nulliparous women. Birth 2020, 47, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlough, M.; Chetwynd, E.; Muthler, S.; Page, C. Maternity Units in Rural Hospitals in North Carolina: Successful Models for Staffing and Structure. South. Med. J. 2021, 114, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Abalos, E.; Chamillard, M.; Ciapponi, A.; Colaci, D.; Comandé, D.; Diaz, V.; Geller, S.; Hanson, C.; Langer, A.; et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: A pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet 2016, 388, 2176–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter, V.; Nethery, E.; Kopas, M.L.; Wurz, H.; Sitcov, K.; Caughey, A.B. Comparison of Midwifery and Obstetric Care in Low-Risk Hospital Births. Obs. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Toribio, M.; Bravo, P.; Llupià, A. Exploring women’s experiences of participation in shared decision-making during childbirth: A qualitative study at a reference hospital in Spain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.R.; Yim, I.S. A systematic review of concepts related to women’s empowerment in the perinatal period and their associations with perinatal depressive symptoms and premature birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphle, S.; Vaughan, G.; Subedi, M. Respectful Maternity Care in South Asia: What Does the Evidence Say? Experiences of Care and Neglect, Associated Vulnerabilities and Social Complexities. Int. J. Womens Health 2022, 14, 847–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, K.P.; Molina, R.L.; Quist-Nelson, J.; Wangerien, L.; Harris, K.; Weiseth, A.L.; Edmonds, J.K. Supporting patient autonomy through respectful labor and childbirth healthcare services. Semin. Perinatol. 2025, 49, 152048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornelsen, J.; Stoll, K.; Grzybowski, S. Stress and anxiety associated with lack of access to maternity services for rural parturient women. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2011, 19, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blythe, M.; Istas, K.; Johnston, S.; Estrada, J.; Hicks, M.; Kennedy, M. Patient Perspectives of Rural Kansas Maternity Care. Kans. J. Med. 2021, 14, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minion, S.C.; Krans, E.E.; Brooks, M.M.; Mendez, D.D.; Haggerty, C.L. Association of Driving Distance to Maternity Hospitals and Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, E. The effect of hospital maternity ward closures on maternal and infant health. Am. J. Health Econ. 2025, 11, 201–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statz, M.; Evers, K. Spatial barriers as moral failings: What rural distance can teach us about women’s health and medical mistrust author names and affiliations. Health Place. 2020, 64, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miewald, C.; Klein, M.C.; Ulrich, C.; Butcher, D.; Eftekhary, S.; Rosinski, J.; Procyk, A. “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone”: The role of maternity care in community sustainability. Can. J. Rural Med. 2011, 16, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- N.C. Maternal and Infant Health Data Dashboard. Available online: https://www.dph.ncdhhs.gov/programs/title-v-maternal-and-child-health-block-grant/nc-maternal-and-infant-health-data-dashboard (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Hughes, C.S.; Schmitt, S.; Passarella, M.; Lorch, S.A.; Phibbs, C.S. Who’s in the NICU? A population-level analysis. J. Perinatol. 2024, 44, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, W.N.; Wasserman, J.R.; Goodman, D.C. Regional Variation in Neonatal Intensive Care Admissions and the Relationship to Bed Supply. J. Pediatr. 2018, 192, 73–79.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, D.C.; Ganduglia-Cazaban, C.; Franzini, L.; Stukel, T.A.; Wasserman, J.R.; Murphy, M.A.; Kim, Y.; Mowitz, M.E.; Tyson, J.E.; Doherty, J.R.; et al. Neonatal Intensive Care Variation in Medicaid-Insured Newborns: A Population-Based Study. J. Pediatr. 2019, 209, 44–51.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, E.M.; Liu, J.; Lu, T.; Joshi, N.S.; Gould, J.; Lee, H.C. Evaluating Epidemiologic Trends and Variations in NICU Admissions in California, 2008 to 2018. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, C.P.; Chetwynd, E.; Zolotor, A.J.; Holmes, G.M.; Hawes, E.M. Building the clinical and business case for opening maternity care units in critical access hospitals. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torio, C.M.; Moore, B.J. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2013. In Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D.; Tuttle, M.S.; Gilbertson, M.; Wharton, K.D. Local Capacity for Emergency Births in Rural Hospitals Without Obstetrics Services. J. Rural. Health 2021, 37, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Casey, M.M.; Hung, P.; Han, X.; Prasad, S.; Moscovice, I.S. The Rural Obstetric Workforce in US Hospitals: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Rural. Health 2015, 31, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musie, M.R.; Tagutanazvo, O.B.; Sepeng, N.V.; Mulaudzi, F.M.; Hlongwane, T. A scoping review on continuing professional development programs for midwives: Optimising management of obstetric emergencies and complications. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.; Henning-Smith, C.E.; Casey, M.M.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Access To Obstetric Services In Rural Counties Still Declining, With 9 Percent Losing Services, 2004–2014. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1663–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, C.E.; O’Hanlon, K.; Kozhimannil, K.B.; Interrante, J.D. Financial challenges of providing obstetric services at rural US hospitals. J. Rural Health 2025, 41, e70082. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Leonard, S.A.; Handley, S.C.; Passarella, M.; Main, E.K.; Lorch, S.A.; Phibbs, C.S. Obstetric Volume and Severe Maternal Morbidity Among Low-Risk and Higher-Risk Patients Giving Birth at Rural and Urban US Hospitals. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e232110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Birth Centers; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Kilpatrick, S.J.; Menard, M.K.; Zahn, C.M.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s; Callaghan, W.M. Obstetric care consensus #9: Levels of maternal care: (Replaces obstetric care consensus number 2, February 2015). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, B19–B30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simpson, C.; McDonald, F. The deficit perspective. In Rethinking Rural Health Ethics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carrel, M.; Keino, B.C.; Novak, N.L.; Ryckman, K.K.; Radke, S. Bypassing of nearest labor & delivery unit is contingent on rurality, wealth, and race. Birth 2023, 50, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Hospital | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC (n = 402) | Comparison (n = 593) | ||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | Chi-Square p-Value | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.08 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 279 | (69.4) | 444 | (74.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68 | (16.9) | 72 | (12.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 44 | (10.9) | 51 | (8.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 10 | (2.5) | 25 | (4.2) | |

| Asian | 1 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.2) | |

| Preferred language | 0.06 | ||||

| English | 232 | (57.7) | 295 | (49.8) | |

| Spanish | 169 | (42.0) | 292 | (49.2) | |

| Arabic | 1 | (0.2) | 1 | (0.2) | |

| Sign language | 0 | 0 | 2 | (0.3) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 3 | (0.5) | |

| Insurance at Delivery | <0.001 | ||||

| Medicaid | 276 | (68.4) | 550 | (92.8) | |

| Private | 59 | (14.7) | 31 | (5.2) | |

| Uninsured | 67 | (11.2) | 12 | (2.0) | |

| Maternal age | 0.91 | ||||

| 16–20 | 50 | (12.4) | 71 | (12.0) | |

| 21–25 | 123 | (30.6) | 175 | (29.5) | |

| 26–30 | 102 | (25.4) | 141 | (23.8) | |

| 31–35 | 80 | (19.9) | 122 | (20.6) | |

| 36–40 | 38 | (9.5) | 68 | (11.5) | |

| 41–45 | 9 | (2.2) | 16 | (2.7) | |

| Parity | 0.96 | ||||

| Multipara | 259 | (64.4) | 387 | (65.3) | |

| First birth | 128 | (31.8) | 184 | (31.0) | |

| Grand multipara (>4 births) | 15 | (3.7) | 22 | (3.7) | |

| History of preterm birth (<37 completed weeks gestation) | 38 | (9.5) | 50 | (8.4) | 0.58 |

| Variable | Hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCC (N = 392) | Comparison (N = 593) | |||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | OR (95% CI) | Wald Chi-Square p-Value | |

| Type of labor | ||||||

| Spontaneous | 245 | (62.5) | 384 | (64.8) | (ref) | |

| Induced | 125 | (31.9) | 163 | (27.5) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.20 |

| Scheduled Cesarean Section | 22 | (5.6) | 46 | (7.8) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.3) | 0.29 |

| Delivery Service Type | ||||||

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 6 | (1.5) | 499 | (84.2) | (ref) | |

| Family Medicine | 267 | (68.1) | 72 | (12.1) | 0.003 (0.0, 0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Certified Nurse Midwifery | 119 | (30.4) | 22 | (3.7) | 0.002 (0.0, 0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Delivery type | ||||||

| Vaginal | 340 | (86.7) | 502 | (84.7) | (ref) | |

| First Cesarean Section | 33 | (8.4) | 54 | (9.1) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 0.66 |

| Repeat Cesarean Section | 19 | (4.9) | 37 | (6.2) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) | 0.34 |

| Epidural use (vaginal only) a | ||||||

| No | 146 | (42.9) | 204 | (40.6) | (ref) | |

| Yes | 194 | (57.1) | 298 | (59.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.51 |

| Birth outcome | ||||||

| Live birth | 390 | (99.5) | 592 | (99.8) | (ref) | |

| Intrauterine fetal demise | 2 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.01) | 0.3 (0.0, 3.6) | 0.37 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage > 1000 mL | ||||||

| No | 362 | (92.4) | 563 | (94.9) | (ref) | |

| Yes | 30 | (7.7) | 30 | (5.1) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.10 |

| Gestational age at birth | ||||||

| Term (<37 weeks) | 386 | (98.5) | 575 | (97.0) | (ref) | |

| Preterm (≥37 weeks) | 6 | (1.5) | 18 | (3.0) | 2.0 (0.8, 5.1) | 0.14 |

| Birthweight | ||||||

| Low (<2500 g) | 8 | (2.0) | 13 | (2.2) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.7) | 0.83 |

| Normal (2500 to <4000 g) | 359 | (91.6) | 528 | (89.0) | (ref) | |

| Large for gestational age (≥4000 g) | 25 | (6.4) | 52 | (8.8) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 0.17 |

| Apgar score at five minutes | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t-test | |

| 8.8 | (0.66) | 8.9 | (0.56) | p = 0.22 | ||

| Neonatal intensive care unit stay b | ||||||

| No | 382 | (97.5) | 394 | (66.4) | (ref) | |

| Yes | 10 | (2.5) | 199 | (33.6) | 19.3 (10.1, 37.0) | <0.0001 |

| Infant Feeding Status at Discharge | ||||||

| Any breastfeeding | 353 | (90.1) | 552 | (93.2) | (ref) | |

| Only formula feeding | 37 | (9.4) | 40 | (6.8) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.12 |

| N/A | 2 | (0.5) | 1 | (0.1) | -- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wouk, K.; Chetwynd, E.; Sheffield, E.C.; Holder, M.G.; Holder, K.; Higgins, I.C.A.; Barker, M.; Smith, T.; van Heerden, B.; Iglesias, D.; et al. Bridging the Gap: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a New Rural Maternity Care Center Amid Nationwide Closures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010102

Wouk K, Chetwynd E, Sheffield EC, Holder MG, Holder K, Higgins ICA, Barker M, Smith T, van Heerden B, Iglesias D, et al. Bridging the Gap: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a New Rural Maternity Care Center Amid Nationwide Closures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleWouk, Kathryn, Ellen Chetwynd, Emily C. Sheffield, Marni Gwyther Holder, Kelly Holder, Isabella C. A. Higgins, Moriah Barker, Tim Smith, Breanna van Heerden, Dana Iglesias, and et al. 2026. "Bridging the Gap: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a New Rural Maternity Care Center Amid Nationwide Closures" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010102

APA StyleWouk, K., Chetwynd, E., Sheffield, E. C., Holder, M. G., Holder, K., Higgins, I. C. A., Barker, M., Smith, T., van Heerden, B., Iglesias, D., Dotson, A., & Helton, M. (2026). Bridging the Gap: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a New Rural Maternity Care Center Amid Nationwide Closures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010102