1. Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that a lack of social connection is associated with poor health [

1]. Among people of working age, labor participation is not only necessary for financial stability but also for maintaining social contact [

2,

3]. Several empirical studies have reported that unemployment is associated with a decline in indicators of social participation [

4,

5,

6].

Welfare programs in many countries provide unemployed individuals with financial assistance while requiring them to return to work to enhance their economic self-reliance. Governments in several countries have implemented welfare reforms with employment obligations for program recipients, though some studies have demonstrated that such reforms may harm recipients’ health [

7]. Instead, more recent arguments call for the well-being of recipients to be the target of welfare programs including labor participation support [

7,

8].

Although previous studies of welfare programs or job training have investigated the effectiveness of employment support on labor, health, or behavioral outcomes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], the processes underlying these programs have not been well described. Outcomes are often used as the primary index for service effectiveness, though outcomes are influenced by conditions other than program effectiveness. In contrast, process measures have been used to assess the critical steps affecting the quality of services [

15]. While case management, counseling and encouragement have been suggested as effective employment support processes in the existing literature [

9,

13,

14], to our knowledge, no systematic process evaluation frameworks exist for employment-support social work for welfare recipients. This lack of a systematic framework precludes evidence-based improvements in service quality.

Accordingly, this study has two objectives. First, to specify a standard employment support process with consideration of recipients’ well-being. Second, to develop and validate an assessment tool for this process, the Index of Social Work Process in Promoting Social Participation of Welfare Recipients (SWP-PSP).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Domain and Item Development

We conducted a review of existing literature investigating the employment support process and social work competencies. We referred to the National Occupational Standards for Social Work [

16] in the UK, the Subject Benchmark Statement [

17] in the UK, Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards [

18] in the United States, and Practical skills required for certified social workers [

19] in Japan because these standards are widely cited in standard setting of social work. We extracted six concepts commonly included in these quality standards, namely: (1) interpersonal relationship building; (2) support for appropriate decision-making; (3) flexibility for changes; (4) development and coordination of social resources; (5) provision of tailored services or information; (6) helping build the confidence of service users by specifying their strengths. Given that both (3) and (5) address adaptable skills in response to contexts, we combined them, resulting in five concepts extracted from the social work field.

We also referred to theories in human resource management for enhancing employees’ motivation and performance, which we considered would provide a technical rationale for the process of social workers helping recipients. By referring to Transformational Leadership [

20], Leader–Member Exchange theory [

21,

22,

23,

24], Self-Determination theory [

25,

26], and Goal Setting theory [

27,

28], we extracted five concepts related to social work process, namely: (a) trust building, (b) active listening, (c) suggesting goal options, (d) helping gain confidence, and (e) timely information provision. Since (a) trust building inevitably requires (b) active listening, we recognized them as conceptually inseparable, resulting in four concepts.

Finally, we integrated these extracted concepts into five domains, namely: Effective Relationship, Deliberative Support, Positive Feedback, Tailored Information, and Network Development. The conceptual integration is described in

Supplemental Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

We prepared item pools using the extracted domains and referring to 43 existing measurement batteries in studies of leadership, coaching, psychological counseling, career counseling, and business networking. We searched PubMed and Web of Science with keywords related to the five domains, and prepared an item pool of 75 items for further discussion. The five domains and examples of item drafts are shown in

Supplemental Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

2.2. Content and Face Validity

We recruited experts during March–May 2024 using snowball sampling. The inclusion criterion was being an academic researcher or practitioner of Public Livelihood Support (PLS) social work with years of practice experience as a PLS social worker. Five eligible experts (four academic researchers and one ex-PLS social worker) consented to participation in this study. All of them had years of experience in local welfare offices. Three were serving in supervisory positions. Two of them had experience as policy advisors for central and local governments on welfare reform and civil worker training. We obtained experts’ feedback through an online focus group discussion on 22 August 2024, followed by feedback via e-mail.

2.3. Reliability and Criterion-Related Validity

The cross-sectional survey was conducted from November 2024 to January 2025. Snowball sampling was implemented through the four experts’ professional networks to recruit PLS social workers. In addition, we recruited respondents from two municipal welfare offices in the greater metropolitan area for the survey. The inclusion criterion was being a current or ex-PLS social worker. Participants anonymously completed the online questionnaire after providing informed consent at the beginning of the survey. The survey asked participants to reflect their usual support process with case recipients. All items of the SWP-PSP were scored using a 6-point rating ranging from 1 (“never”) to 6 (“always”). Additionally, we obtained information about participants’ gender, age, years of experience as a PLS social worker, and certification status. In the Japanese PLS system, the required services and processes related to welfare support are identical for practitioners regardless of their social work certification status only if they receive a short-term training, while the national licensure for social workers requires specialty educational credits for licensure eligibility. Given this context, we used licensure status as a proxy marker of PLS social workers’ specialty educational experience when discerning whether any differences existed between self-rated performance scores.

2.4. Data Analysis

We applied item response theory (IRT) analysis to estimate the discrimination and difficulty for each item. Because the distributions of each item were skewed, we employed conventional dichotomous IRT, in which option 6 (always) was correct (=1) and all other options were incorrect (=0). After the binary transformation, we tested unidimensionality using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), local independence based on Yen’s Q3 statistic [

29] checking the residual correlation matrix of the CFA, and monotonicity using the Mokken Scale Procedure (MSP) [

30]. After excluding a domain that did not meet these assumptions, IRT analysis (two parameters) was conducted in each domain. Discrimination parameters higher than 1.7 are taken as very good according to Baker and Kim [

31], but clear criteria for difficulty do not exist. However, items with difficulty below 0 are considered too easy [

32,

33]. Therefore, we decided to select items with higher discrimination (>2.0) and an acceptable range of difficulty (>0.1). We then conducted criterion-related validation using the total score of adopted items. We used the Utrecht Work Engagement (UWE) scale [

34] as a reference because UWE reflects an individual’s recognition of the meaningfulness of their work [

35,

36] and relates to work performance [

37], which we expected would correlate with the self-evaluation of the process quality of employment support for welfare recipients. Higher SWP-PSP would be expected to predict better social work, which would be expected to be correlated with higher UWE scores. We investigated Pearson’s correlation coefficient with UWE for all participants, as well as for participants stratified by certification status, to examine the differences. For reliability testing, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated in each domain. All analyses were performed using Stata version 17 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Content and Face Validity

The expert panel reached consensus on the significance of relationship building through supportive and open communication, with tailored information to help enhance self-reliance. They also agreed on the importance of resource networking and motivating skills, and that technocratic enforcement of labor participation may not work. The panel advised the revision of domain names and item wording for clarity, as detailed in “The process of item revision in the focus group interview” in the

Supplementary Materials. Subsequently, the pilot measure with 44 items in five domains (Development of Effective Relationship, Support for Deliberation, Positive Feedback, Provision of Tailored Information, and Network Development) was prepared for further validation testing.

3.2. Reliability and Criterion-Related Validity

3.2.1. Demographic Characteristics of Cross-Sectional Research

The questionnaire was completed by 139 PLS social workers. Participants’ average age was 35.7, and their years of experience were approximately divided equally into three categories. The certified social workers comprised 43.2% of participants. The mean score of certified social workers was significantly greater than that of social workers without certification by 10.75 points (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: z = −2.71,

p = 0.007). The mean scores for each domain were 5.31, 4.77, 4.86, 5.02, and 4.83, respectively (

Table 1).

3.2.2. Item Selection by Item Response Theory Analysis

The CFA of the five domains resulted in a root mean square error of approximation of 0.078, standardized root mean square residual of 0.08, and comparative fit index value of 0.718. The root mean square error of approximation and standardized root mean square residual values were acceptable, but the comparative fit index value was not sufficient [

38]. We then implemented EFA to examine whether the eigenvalues and the contributions of the first factor were sufficiently large in each domain. The first and second factors were similar in domain 1. Thus, the unidimensionality of domain 1 was not confirmed. The maximum value in residual correlation of CFA between five domains was 0.044; this value was close to zero, confirming local independence [

29]. MSP showed that domain 1 did not converge. Therefore, we determined that monotonicity in domain 1 was rejected. Although one item of domain 2 remained, other items were selected in one scale (H = 0.48). In domains 3 to 5, all items were selected and the H coefficient was greater than 0.5 [

30]. Monotonicity was confirmed in domains 2 to 5. Given that the unidimensionality and monotonicity in domain 1 were not confirmed, we decided to omit IRT analysis of that domain. IRT analysis was conducted in each of the remaining four domains, and we checked the discrimination and difficulty of each item. The number of items with discrimination >2.0 and difficulty >0.1 was 6 in domain 2 (the item not selected in the MSP was excluded), 5 in domain 3, 3 in domain 4, and 6 in domain 5. The total number of included items was 20 (

Table 2).

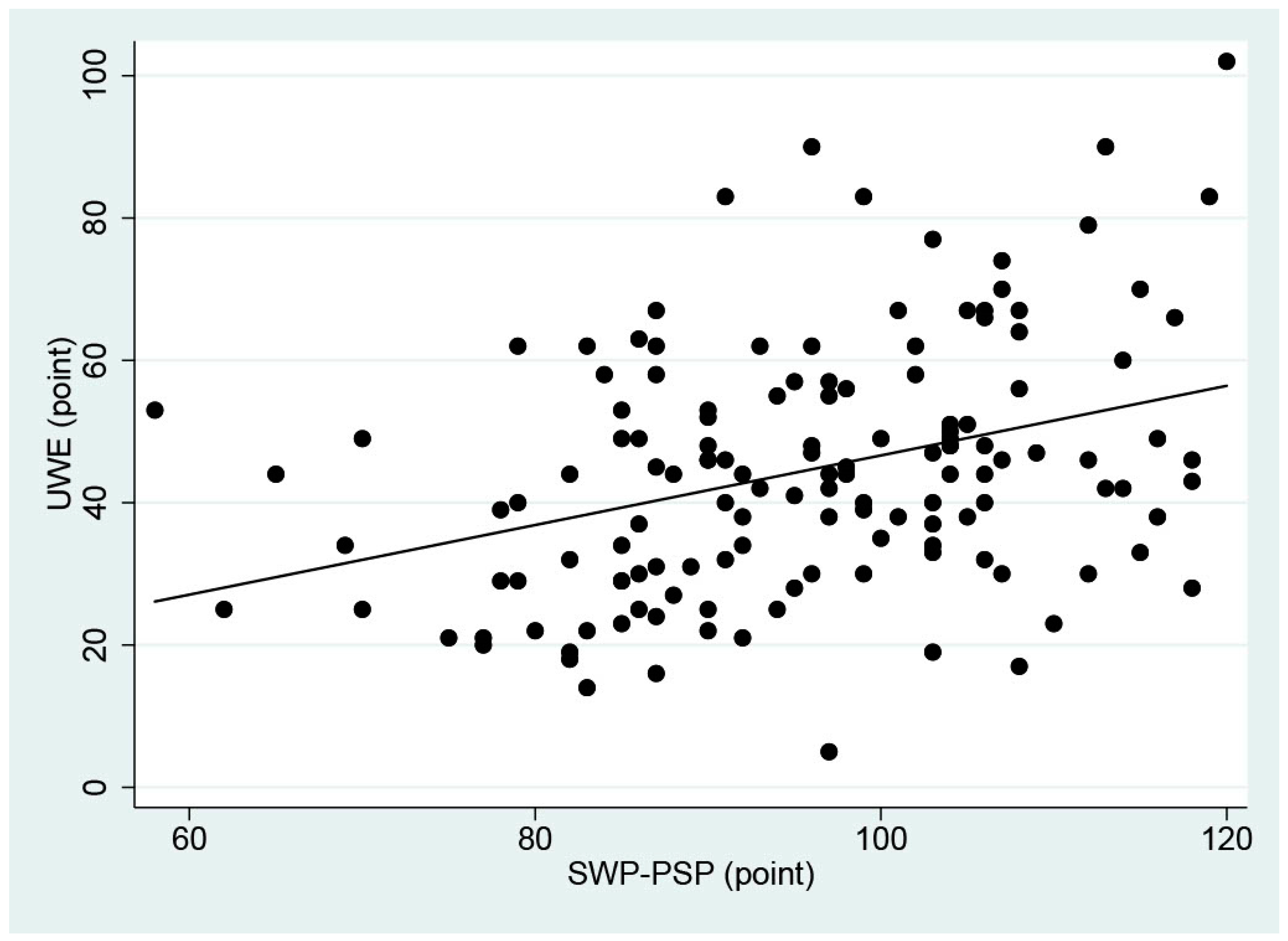

3.2.3. Criterion-Related Validity

The correlation coefficient between the non-binary total score of selected SWP-PSP items and UWE score was calculated. The coefficient was 0.35, demonstrating a moderate correlation [

39] (

Figure 1). When the total scores were stratified into certified social workers and social workers without certification, the coefficient was 0.44 for certified workers, and 0.26 for those without certification. We examined the measurement invariance across the two groups. The results indicated that the factor loadings were similar between those participants with and without certification, suggesting metric invariance. However, scalar invariance could not be confirmed because of the limited sample size. Although the correlations with UWE scores by domain were investigated, no explicit changes from total scores were found. Additionally, there was no correlation between years of experience and UWE scores (r = 0.10).

3.2.4. Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for domains 2–5 were 0.80, 0.86, 0.77, and 0.84, respectively.

4. Discussion

Although CFA showed a weak model fit between five domains, EFA confirmed unidimensionality in each domain except for domain 1. Twenty items with discrimination >2.0 and difficulty >0.1 were selected from the four domains using IRT analysis. The correlation coefficient between SWP-PSP and UWE was moderate according to Cohen’s criterion [

39]. Certified social workers with specialized education in social work demonstrated a stronger correlation with UWE. Cronbach’s alpha reached the acceptable range [

40]. Thus, the current results support the reliability and validity of the SWP-PSP.

Domain 1 failed to exhibit unidimensionality in EFA and monotonicity in MSP—aspects that require further consideration. The small difference in scores of the domain items between respondents indicated a ceiling effect, presumably because basic communication was being measured. However, we still consider the concept of the domain per se remains important and essential for social work process. Further research is needed for better operationalization of the domain items.

PLS social workers without certification exhibited a weaker correlation with UWE scores compared with certified social workers. Because most of these workers were originally office clerks, they may evaluate their own performance for goals other than effective support for social participation of welfare recipients (e.g., efficiently completing clerical work). Current PLS social worker training is typically focused on the operation of PLS law and systems, with less emphasis on the ultimate goal to achieve recipient’s well-being. Thus, it may be helpful to develop training programs for PLS social workers in early career and evaluate the training process using the SWP-PSP.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, performance assessment of the developed scale provides evidence of measurement reliability, and construct and convergent validity. However, predictive validity has not yet been demonstrated with outcomes such as the rate of work return and health improvement among program recipients. Furthermore, the scale still needs to demonstrate proof of measure responsiveness to performance change. Second, although we relied on experts with rich practice experience and institutional knowledge, the applicability of the measure remains to be shown with a wider range of PLS social workers with diverse skills and experiences. A larger probabilistic sample could also overcome the issues of potential no-response bias and inter-group comparability with scalar invariance. Participants completed the web survey anonymously, which meant that detailed information about their backgrounds was not obtained. Third, we still need to refine the operationalized items to realize the domain concept related to effective relationship building. The application of the scale in the real-world quality management of PLS social work services would benefit from addressing these remaining issues in future research. Fourth, the current form of the SWP-PSP was designed to reflect the welfare service practice in the Japanese context. Although we expect it to be usable across Japan, further efforts to refine relevant domains may be necessary for cross-country comparisons of different political and institutional settings. The detailed presentation of the measure development processes described in this study could help researchers interested in cross-country adaptations of the scale concepts. We believe the comparative scale development will facilitate research to identify quality leverages of welfare programs and related policies to be reformed for recipients’ wellbeing and social inclusion through labor participation.

Despite the study limitations, to our knowledge, the SWP-PSP is the first evaluation measure with rigorous item selection designed to systematically assess the process of employment support for welfare recipients. With further refinement and validation of the measure could support social workers’ self-reflection and growth of their skills. It could also advance systemic skills training and evaluation of early career social workers.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we developed the SWP-PSP as a measure of social workers’ capacity for helping welfare recipients resume their social participation and work for well-being purposes. Evidence of the scale’s measurement reliability and validity was provided. With further refinement, the measure could serve as a tool for the empirical assessment of social work processes for service quality improvement and professional growth of social workers.

Author Contributions

Y.T. was responsible for data curation, data analysis and writing the manuscript; H.H. provided supervision and edited and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering), grant number 22K18404.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of The University of Tokyo on July 17, 2024 (2024156NI).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy rules.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the members of the experts’ panel, the municipal officers who distributed the URL of our online questionnaire, the PLS social workers who responded to our online questionnaire, and Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Social connection as a public health issue: The evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahoda, M. Employment and Unemployment: A Social-Psychological Analysis; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.B. Work, Unemployment and Mental Health; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlan, L. Unemployment and social exclusion. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 164, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckhoff, M.; Gash, V. Unemployed and alone? Unemployment and social participation in Europe. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2015, 35, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, L.; Suppa, N. Bowling alone or bowling at all? The effect of unemployment on social participation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 133, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, S.; Bentley, L.; Rose, T.; Whitehead, M.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Barr, B. Effects on mental health of a UK welfare reform, Universal Credit: A longitudinal controlled study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e157–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Public Health (Editorial). Income, health, and social welfare policies. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e127. [CrossRef]

- Haberecht, K.; Baumann, S.; Bischof, G.; Gaertner, B.; John, U.; Freyer-Adam, J. Do brief alcohol interventions among unemployed at-risk drinkers increase re-employment after 15 month? Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, A.; Høgelund, J.; Gørtz, M.; Rasmussen, K.S.; Houlberg, H.S.B. Employment effects of active labor market programs for sick-listed workers. J. Health Econ. 2017, 52, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, D.M.; Zanis, D.A.; Wesnoski, S.A.; Domis, S.W. An integrated drug counseling and employment intervention for methadone clients. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2009, 41, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, M.A.; McKay, J.; Ketterlinus, R.D.; McLellan, A.T. Potential barriers to work for substance-abusing women on welfare–Findings from the CASAWORKS for Families pilot demonstration. Eval. Rev. 2003, 27, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, J.; Hogue, A.; Dauber, S.; Dasaro, C.; McKay, J.R. Does coordinated care management improve employment for substance-using welfare recipients? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clayton, S.; Bambra, C.; Gosling, R.; Povall, S.; Misso, K.; Whitehead, M. Assembling the evidence jigsaw: Insights from a systematic review of UK studies of individual-focused return to work initiatives for disabled and long-term ill people. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Training Organisation for Personal Social Services. The National Occupational Standards for Social Work; The Training Organisation for Personal Social Services: Leeds, UK, 2002; Available online: https://basw.co.uk/sites/default/files/resources/basw_32232-7_0.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. Subject Benchmark Statement: Social Work; QAA: Gloucester, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-social-work.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Council on Social Work Education. Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS); CSWE: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/bb5d8afe-7680-42dc-a332-a6e6103f4998/2022-Educational-Policy-and-Accreditation-Standards-(EPAS).pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Japanese Association of Certified Social Workers. Practical Skills Required for Certified Social Workers as Social Work Professionals; Japanese Association of Certified Social Workers: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000158098.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Wright, B.E.; Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. Pulling the levers: Transformational leadership, public service motivation, and mission valence. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B.; Dysvik, A. Perceived investment in permanent employee development and social and economic exchange perceptions among temporary employees. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 2499–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.; Novak, M.A.; Sommerkamp, P. The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction–Testing a dual attachment model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1982, 30, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopman, L.M.; Kalshoven, K.; Boon, C. When health care workers perceive high-commitment HRM will they be motivated to continue working in health care? It may depend on their supervisor and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere–an extension of Cognitive Evaluation Theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Connell, J.P.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination in a work organization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Cervone, D. Self-evaluative and self-efficacy mechanisms governing the motivational effects of goal systems. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation—A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.M. Effects of local item dependence on the fit and equating performance of the Three-Parameter Logistic Model. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1984, 8, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokken, R.J. A Theory and Procedure of Scale Analysis with Applications in Political Research; Walter de Gruyter & Co.: Berlin, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, F.B.; Kim, S.H. Item Response Theory: Parameter Estimation Techniques; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, D.; Chung, U.S.; Lee, J.J. Identification of central symptoms in depression of older adults with the Geriatric Depression Scale using network analysis and item response theory. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deters, L.B.; Silvia, P.J.; Kwapil, T.R. The Schizotypal Ambivalence Scale: An item response theory analysis. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kosugi, S.; Suzuki, A.; Nashiwa, H.; Kato, A.; Sakamoto, M.; Irimajiri, H.; Amano, S.; Hirohata, K.; et al. Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Z.S.; Peters, J.M.; Weston, J.W. The struggle with employee engagement: Measures and construct clarification using five samples. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1201–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development, 5th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).