Evidenced Interventions Supporting the Psychological Wellbeing of Disaster Workers: A Rapid Literature Review

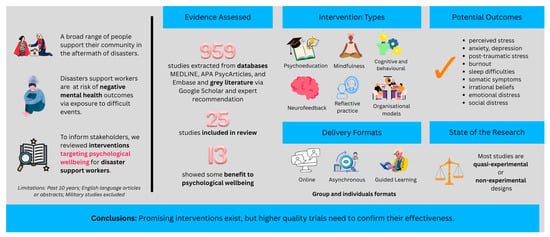

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- What interventions are used to enhance psychological well-being among disaster response workers?

- 2.

- How are these interventions implemented and evaluated?

- 3.

- What is the evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions?

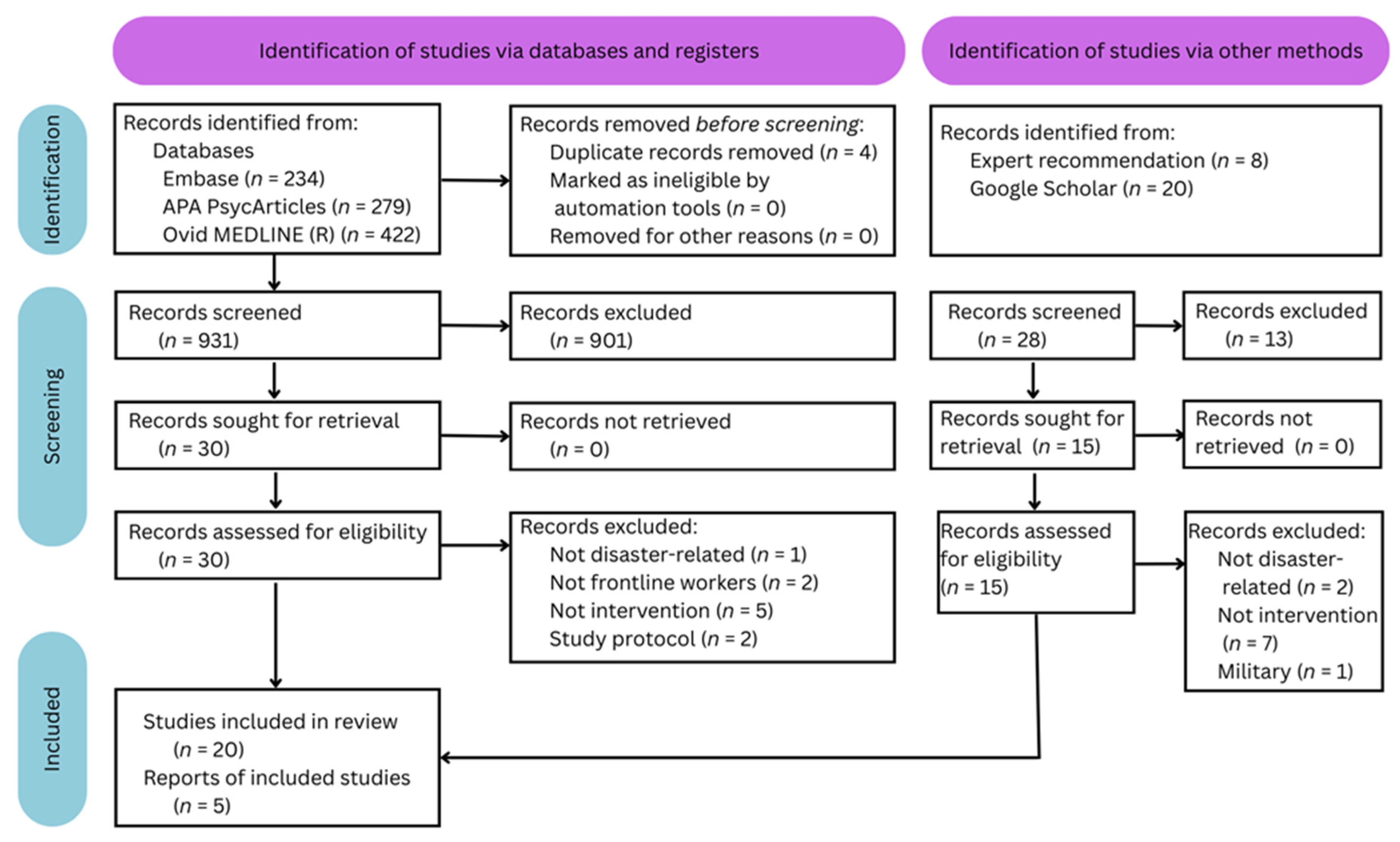

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

Risk of Bias

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.3.1. Published Literature

2.3.2. Grey Literature

3. Results

3.1. Interventions Supporting Workers Without Manifest Symptoms

3.1.1. Critical Incident Stress Debriefing

3.1.2. Rational Emotive Behavioural Coaching

3.2. Interventions Supporting Workers with Sub-Clinical Symptoms

3.2.1. Intensive Neurofeedback Protocol

3.2.2. Stepped-Care Models (Variants of Psychological First Aid and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy)

3.3. Interventions Supporting Workers with Clinical Symptoms

3.3.1. Urgent Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (URG-EMDR)

3.3.2. Culturally-Relevant Jungian Archetypes

3.4. Education and Preparation Models

3.4.1. Mental Health Literacy and Stress Management Psychoeducation

3.4.2. Cognitive Behavioural, Mindfulness, and Acceptance Training

3.4.3. Psychological First Aid Training

3.5. Reflective Practice (Supervision and Peer Support)

3.5.1. Integrated Supervision Model

3.5.2. Peer Support

3.6. Organisational Frameworks

3.6.1. Trauma-Informed Practice

3.6.2. Moral Injury Prevention

3.6.3. Preparation, Response, and Recovery

3.6.4. Whole-of-Organisation

3.7. Measures Identifying Vulnerable Workers

3.7.1. Symptoms—Compassion Fatigue and Self-Triage for PTSD

3.7.2. Resilience Processes—Coping Style and Perceived Competence

3.8. Quality of Studies and Effect Sizes

4. Discussion

4.1. Evidence-Based Interventions

4.2. Group, Leader, or Organisational Approaches

4.3. The Impact of COVID-19

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI/AN | American Indian and Alaska Native |

| CISD | Critical incident stress debriefing |

| CSV | Comma separated values |

| DWRT | Disaster worker resilience training |

| PCS-DMHW | Perceived competence scale for disaster mental health workforce |

| PHQ-8 | Patient Health Questionnaire–8-item |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| REBC | Rational-emotive behavioural coaching |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

References

- Berger, W.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Figueira, I.; Marques-Portella, C.; Luz, M.P.; Neylan, T.C.; Marmar, C.R.; Mendlowicz, M.V. Rescuers at risk: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Geng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety and depression among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health. 2022, 10, 984630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Dhandapani, M.; Cyriac, M.C. Burnout and Resilience among Frontline Nurses during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Care Center, North India. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocker, F.; Joss, N. Compassion Fatigue among Healthcare, Emergency and Community Service Workers: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzea, V.-E.; Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Vlachaki, S.-A.; Melidoniotis, E.; Pistolla, G. PTSD, burnout and well-being among rescue workers: Seeking to understand the impact of the European refugee crisis on rescuers. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. Social and occupational factors associated with psychological wellbeing among occupational groups affected by disaster: A systematic review. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. WMO Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses From Weather, Climate and Water Extremes (1970–2019). 2023. Available online: https://primarysources.brillonline.com/browse/climate-change-and-law-collection/wmo-atlas-of-mortality-and-economic-losses-from-weather-climate-and-water-extremes-19702019;cccc026820231218 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Anikeeva, O.; Hansen, A.; Varghese, B.; Borg, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, J.; Bi, P. The impact of increasing temperatures due to climate change on infectious diseases. BMJ 2024, 387, e079343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S. APS Disaster Response Network psychologists help in the field following the January Bourke St incident in Melbourne. APS InPsych 2017, 39. Available online: https://psychology.org.au/inpsych/2017/april/burke (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Watson, P.; Bell, C.C.; Bryant, R.A.; Brymer, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Gersons, B.P.; de Jong, J.T.; Layne, C.M.; et al. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and Mid–Term Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry 2007, 70, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Suo, Y.; Wei, X.; Luo, Y. Resilience enhancement interventions for disaster rescue workers: A systematic review. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2025, 33, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyond Blue, Good Practice Framework for Mental Health and Wellbeing in Police and Emergency Services Organisations. 2020. Available online: https://edge.sitecorecloud.io/beyondblue1-beyondblueltd-p69c-fe1e/media/Project/Sites/beyondblue/PDF/Resource-Library/Workplace/bl2042_goodpracticeframework_a4.pdf?sc_lang=en (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Winders, W.T.; Bustamante, N.D.; Garbern, S.C.; Bills, C.; Coker, A.; Trehan, I.; Osei-Ampofo, M.; Levine, A.C. Establishing the Effectiveness of Interventions Provided to First Responders to Prevent and/or Treat Mental Health Effects of Response to a Disaster: A Systematic Review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 15, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, C.S.; Pfefferbaum, B. Mental Health Response to Community Disasters. JAMA 2013, 310, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahernejad, S.; Ghaffari, S.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Wesemann, U.; Farahmandnia, H.; Sahebi, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder in medical workers involved in earthquake response: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, C.; Montero, M.; Serrano-Ibáñez, E.R.; de la Vega, A.; Pulido, M.A.G. Psychological interventions for healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Stress Health 2023, 39, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smela, B.; Toumi, M.; Świerk, K.; Francois, C.; Biernikiewicz, M.; Clay, E.; Boyer, L. Rapid literature review: Definition and methodology. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2023, 11, 2241234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wesemann, U.; Mahnke, M.; Polk, S.; Bühler, A.; Willmund, G. Impact of Crisis Intervention on the Mental Health Status of Emergency Responders Following the Berlin Terrorist Attack in 2016. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 14, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.G.; Wilkinson, A.; Turner, M.J.; Haslam, C.O.; Barker, J.B. Into the fire: Applying Rational Emotive Behavioral Coaching (REBC) to reduce irrational beliefs and stress in fire service personnel. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2021, 28, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatti, B.; Girone, N.; Conti, D.; Celebre, L.; Macellaro, M.; Molteni, L.; Vismara, M.; Bosi, M.; Colombo, A.; Dell’Osso, B. Intensive Neurofeedback Protocol: An Alpha Training to Improve Sleep Qualityand Stress Modulation in Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Apilot Study. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2023, 20, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla, R.; Felez-Nobrega, M.; McGreevy, K.R.; Monistrol-Mula, A.; Bravo-Ortiz, M.-F.; Bayón, C.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Villaescusa, R.; Muñoz-Sanjosé, A.; Aguilar-Ortiz, S.; et al. Effectiveness of a mental health stepped-care programme for healthcare workers with psychological distress in crisis settings: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, e300697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquinio, C.; Brennstuhl, M.-J.; Rydberg, J.A.; Bassan, F.; Peter, L.; Tarquinio, C.L.; Auxéméry, Y.; Rotonda, C.; Tarquinio, P. EMDR in Telemental Health Counseling for Healthcare Workers Caring for COVID-19 Patients: A Pilot Study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 42, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, J. A Jungian approach to psychological intervention: Using the cultural archetype of the “gourd” image to support Chinese frontline medical staff during COVID-19. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2023, 40, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Chang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Guo, Y.; Gao, B.-L. Effects of Online Psychological Crisis Intervention for Frontline Nurses in COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 937573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yöyen, E.; Baris, T.G.; Sezer, C. Investigation of the Efficiency of Psychological Support Videos as an Approach to the Protection of Mental Health of Medics During the Pandemic Process. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 32, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Shand, F.; Lal, T.J.; Mott, B.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Resilience@Work Mindfulness Program: Results From a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial With First Responders. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Vega, B.; Palao, Á.; Muñoz-Sanjose, A.; Torrijos, M.; Aguirre, P.; Fernández, A.; Amador, B.; Rocamora, C.; Blanco, L.; Marti-Esquitino, J.; et al. Implementation of a Mindfulness-Based Crisis Intervention for Frontline Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Public General Hospital in Madrid, Spain. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 562578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengin, A.C.; Nourry, N.; Severac, F.; Berna, F.; Bemmouna, D.; Costache, M.E.; Fritsch, A.; Frey, I.; Ligier, F.; Engel, N.; et al. Efficacy of the my health too online cognitive behavioral therapy program for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2024, 36, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffey, B.L.; Mackin, D.M.; Rosen, J.; Schwartz, R.M.; Taioli, E.; Gonzalez, A. The disaster worker resiliency training program: A randomized clinical trial. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 94, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, V.M.; Grubin, F.; Vaidya, N.; Maudrie, T.L.; Conrad, M.; Neuner, S.; Jridi, S.; Cook, M.A.; Carson, K.A.; Barlow, A.; et al. Pilot evaluation of a Psychological First Aid online training for COVID-19 frontline workers in American Indian/Alaska Native communities. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1346682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Xiao, T.; Carter, B.; Shearer, J. Evaluation of system based psychological first aid training on the mental health proficiency of emergency medical first responders to natural disasters in China: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, Á.; Abujaber, N.; McBride, K.A.; Blum, P.T.; Wiedemann, N.; Vallières, F. Identifying best practice for the supervision of mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian emergencies: A Delphi study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellins, C.A.; Mayer, L.E.; Glasofer, D.R.; Devlin, M.J.; Albano, A.M.; Nash, S.S.; Engle, E.; Cullen, C.; Ng, W.Y.; Allmann, A.E.; et al. Supporting the well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CopeColumbia response. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, K.; Galván-Durán, A.R.; D’uRso, S.; Garcia, D. The Witness to Witness Program: Helping the Helpers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, V.; Stevelink, S.A.; Greenberg, N. Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda, M.; Chiba, R.; Sasaki, M.; Agustini, E.N.; Mashino, S. A Literature Review on Psychosocial Support for Disaster Responders: Qualitative Synthesis with Recommended Actions for Protecting and Promoting the Mental Health of Responders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Red Cross. Workforce Wellbeing Framework. 2020. Available online: https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/55e654c5-549d-4ce1-ac2b-25d6cbc93268/field-psychologist-briefing_1.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Sun, B.; Hu, M.; Yu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Lou, B. Validation of the Compassion Fatigue Short Scale among Chinese medical workers and firefighters: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylwanowicz, L.; Schreiber, M.; Anderson, C.; Gundran, C.P.D.; Santamaria, E.; Lopez, J.C.F.; Lam, H.; Tuazon, A.C. Rapid Triage of Mental Health Risk in Emergency Medical Workers: Findings From Typhoon Haiyan—CORRIGENDUM. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2018, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolin, S.N.; Flis, A.; Davis, J.J. Work coping, stress appraisal, and psychological resilience: Reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic among health care providers. Psychol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.-Y.; Choi, Y.-K. The Development and Validation of the Perceived Competence Scale for Disaster Mental Health Workforce. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilaran, J.; de Terte, I.; Kaniasty, K.; Stephens, C. Psychological Outcomes in Disaster Responders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effect of Social Support. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, J.J.; Saulsman, L.; Hall, T.; Waters, F. Addressing the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: Learning from a systematic review of early interventions for frontline responders. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. Traumatic stress within disaster-exposed occupations: Overview of the literature and suggestions for the management of traumatic stress in the workplace. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 129, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzailai, N.; Barriball, K.L.; Xyrichis, A. Impact of and mitigation measures for burnout in frontline healthcare workers during disasters: A mixed-method systematic review. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2023, 20, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Xiao, T.; Carter, B.; Chen, P.; Shearer, J. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Mental Health Interventions Delivered by Frontline Health Care Workers in Emergency Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.S.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baetzner, A.S.; Wespi, R.; Hill, Y.; Gyllencreutz, L.; Sauter, T.C.; Saveman, B.-I.; Mohr, S.; Regal, G.; Wrzus, C.; Frenkel, M.O. Preparing medical first responders for crises: A systematic literature review of disaster training programs and their effectiveness. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2022, 30, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Dean, G.; Holmes, L. Supporting the Mental Health and Well-Being of First Responders from Career to Retirement: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Sage, C.A.M.; Amlôt, R.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. Risk and resilience factors affecting the psychological wellbeing of individuals deployed in humanitarian relief roles after a disaster. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Population | Intervention | Comparison [Risk of Bias] | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support to workers without manifest symptoms | ||||

| Wesemann et al., 2019 [20] | Firefighters, police, emergency medical technicians + NGOs following a terrorist attack (n = 55; Germany) | Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) | Non-randomised observational study using independent-samples t-tests (intervention vs no intervention) [high risk] | Psychosocial stressors; quality of life over the past two weeks (physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment); post-traumatic stress symptoms; symptoms of psychiatric disorders |

| Wood et al., 2021 [21] | County Fire and Rescue Volunteers Responsible for Disaster Response (n = 34; UK) | Rational Emotive Behavioural Coaching (REBC) | Quasi-experimental (purposeful allocation) pre-post control design [moderate risk] | Irrational performance beliefs; resilience; hair cortisol concentration; depression; anxiety; stress; presenteeism |

| Support to workers with sub-clinical symptoms | ||||

| Benatti et al., 2023 [22] | Medical doctors (n = 18; Italy) | Intensive Alpha-Increase Neurofeedback Protocol | Pilot efficacy study [high risk] | Sleep quality; stress; burnout |

| Mediavilla et al., 2023 [23] | Health Care Workers with distress (n = 115; Spain) | Doing what Matters (stepped care) with Problem Management+ when distress identified | Analyst-blind, parallel, multicentre RCT (TAU, enhanced with PFA) [low risk] | Anxiety; depression; PTSD |

| Support to workers with clinical symptoms | ||||

| Tarquinio et al., 2020 [24] | Nurses (n = 17; France) | Urgent Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (URG-EMDR) single session video call | Quasi-experimental pilot (no control) pre-post efficacy study [moderate risk] | Depression; anxiety; subjective units of disturbance; fear of going to work; fear for your safety at work |

| Liang et al., 2023 [25] | Physicians and Nursing staff (n = 43; China) | Gourd Symbolism with Jungian Archetype | Repeated cross-sectional design with some reference to case study data [high risk] | Psychologist observed: anxiety; depression; fidgeting; sadness; uncontrollable concern; sense of powerlessness, frustration; tense; insomnia; physical discomfort; guilt and self-reproaching |

| Education and Preparation | ||||

| He et al., 2022 [26] | Nurses working in COVID-19 isolation wards (n = 62; China) | Stress Management Training and Group Post-Event Counselling | Quasi-experimental (no control) pre-post study [high risk] | Anxiety; depression; somatic symptoms |

| Yöyen et al., 2022 [27] | Healthcare professionals (n = 440; Turkey) | Mental health literacy, cognitive and mindfulness video education | Quasi-experimental (no control) pre-post efficacy study [high risk] | Anxiety; depression; challenge; dedication; control |

| Joyce et al., 2019 [28] | Full-time firefighters from Primary Fire and Rescue and Hazmat stations (n = 143; Australia) | Resilience@Work: online-delivered mindfulness education intervention | Cluster pre-post (6-month follow-up) RCT [low risk] | Resilience resources; optimism; active coping; use of emotional and instrumental support |

| Rodriguez-Vega et al., 2020 [29] | Healthcare workers (n = 150; Spain) | Mindfulness-Based Crisis Intervention | Exploratory study with post-intervention assessment [high risk] | Utility perception; safety and feasibility indicators |

| Mengin et al., 2024 [30] | Healthcare workers (n = 155; France) | My Health Too: online CBT and mindfulness psychoeducation for work stress | Multicentric RCT (bibliotherapy control) evaluation [low risk] | Perceived stress; depression; post-traumatic stress symptoms; resilience; insomnia; work-related rumination; credibility of the treatment; satisfaction with treatment; perceived efficacy and utility of sessions |

| Mahaffey et al., 2020 [31] | Disaster responders of Hurricane Sandy (n = 167; U.S.) | The Disaster Worker Resiliency Training Program (DWRT) | Waitlist RCT testing efficacy while controlling for historical changes (trauma exposure) [low risk] | Engagement with healthy lifestyle behaviours; spiritual growth; perceived stress; severity of PTSD symptoms; depression; traumatic exposure |

| O’Keefe et al., 2024 [32] | American Indian and Alaska Native COVID-19 frontline workers (n = 56; U.S.) | Psychosocial skills for COVID-19 Responders, adapted for Frontline Workers in American Indian/Alaska Native Communities | Quasi-experimental (no control) pre-post (1 week and 3 month follow up) observational online pilot evaluation [high risk] | Anxiety; burnout; stress; positive mental health; communal mastery; coping skills; PFA knowledge + skills; satisfaction with training; emotional and social well-being |

| Peng et al., 2024 [33] | Healthcare workers responding to natural disasters (n = 1399; China) | System-Based Psychological First Aid Training | A parallel-group, assessor-blinded, cluster RCT (treatment as usual) [low risk] | PFA knowledge, skills, + attitude; optimistic self-beliefs; professional quality of life; post-traumatic growth |

| Reflective Practice | ||||

| Travers et al., 2022 [34] | Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Stakeholders (n = 37; Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, Australia) | 28 (21 with consensus) features of supervision in the context of mental health and psychosocial support | Delphi study pertaining to supervision quality + purpose with bivariate analyses of gender differences [moderate risk] | Supervision quality and purpose (not measured) |

| Mellins et al., 2020 [35] | Healthcare workers (n = >1500; U.S.) | CopeColumbia, an intervention intended to bolster emotional well-being and increase professional resilience. | A description of the intervention [high risk] | health; health of family + friends; work safety; job responsibilities; financial stability; impact on non-work life (none measured) |

| Organisational Frameworks | ||||

| Weingarten et al., 2020 [36] | Healthcare workers and attorneys (no sample; U.S.) | The Witness to Witness Program for coping with grief, moral injury and distress. | A description the adaption of an intervention to the COVID context [high risk] | Witnessing position (qualitatively measured) |

| Williamson et al., 2018 [37] | NA | Steps to Protect Mental Health in the Face of Moral Dilemmas | Descriptive paper on early support and after-care to reduce moral injury [high risk] | Moral injury (not measured) |

| Umeda et al., 2020 [38] | NA | Recommendations to reduce stressors and stressful situations and improve the management of stress | Literature review and qualitative synthesis of psychosocial supports [moderate risk] | Stressors; chronically stressful situations (not measured) |

| Good Practice Framework, 2020 [12] | NA | Good practice models, principles and recommendations for reducing risk of work-related harm. | A grey literature description of Beyond Blue’s Good Practice Framework [high risk] | Work-related harm (not meeasured) |

| Australian Red Cross, 2020 [39] | NA | Australian Red Cross’ Well-being Support Structure and Methodology | Description of organisational structure, processes to support frontline/emergency workers’ well-being [high risk] | Well-being (not measured) |

| Measures | ||||

| Sun et al., 2016 [40] | Firefighters, police, emergency medical technicians and NGOs following a terrorist attack (Germany) | Chinese Compassion-Fatigue-Short Scale (C-CF-SS) | Validation (confirmatory and exploratory) of a translated scale [low risk] | Compassion fatigue |

| Sylwanowicz et al., 2018 [41] | Responders to Typhoon Haiyan (Philippines) | Psychological Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (PsySTART) | Validation of a scale’s predictive validity for PCL-5 scores four months later (convenience sample) [moderate risk] | Depression; PTSD |

| Rolin et al., 2022 [42] | Healthcare workers (n = 423; U.S.) | The Brief COPE Inventory | Validation of a scale’s ability to measure coping style (cross-sectional, convenience sample) [moderate risk] | Problem- or emotion-focused coping |

| Yoon and Choi, 2019 [43] | Mental health professionals, paraprofessionals, disaster site volunteers, related discipline students (n = 509; South Korea) | Perceived Competence Scale for Disaster Mental Health Workforce (PCS-DMHW) | Validation (confirmatory and exploratory) of a scale (sampling not fully described, probably convenience) [moderate risk] | Individual competence; organisational competence; burnout |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deans, C.; Carter, S. Evidenced Interventions Supporting the Psychological Wellbeing of Disaster Workers: A Rapid Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091454

Deans C, Carter S. Evidenced Interventions Supporting the Psychological Wellbeing of Disaster Workers: A Rapid Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091454

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeans, Carolyn, and Shannon Carter. 2025. "Evidenced Interventions Supporting the Psychological Wellbeing of Disaster Workers: A Rapid Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091454

APA StyleDeans, C., & Carter, S. (2025). Evidenced Interventions Supporting the Psychological Wellbeing of Disaster Workers: A Rapid Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091454