Replication of a Culturally Tailored Tobacco Cessation Intervention for Arab American Men in North Carolina: An Exploratory Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

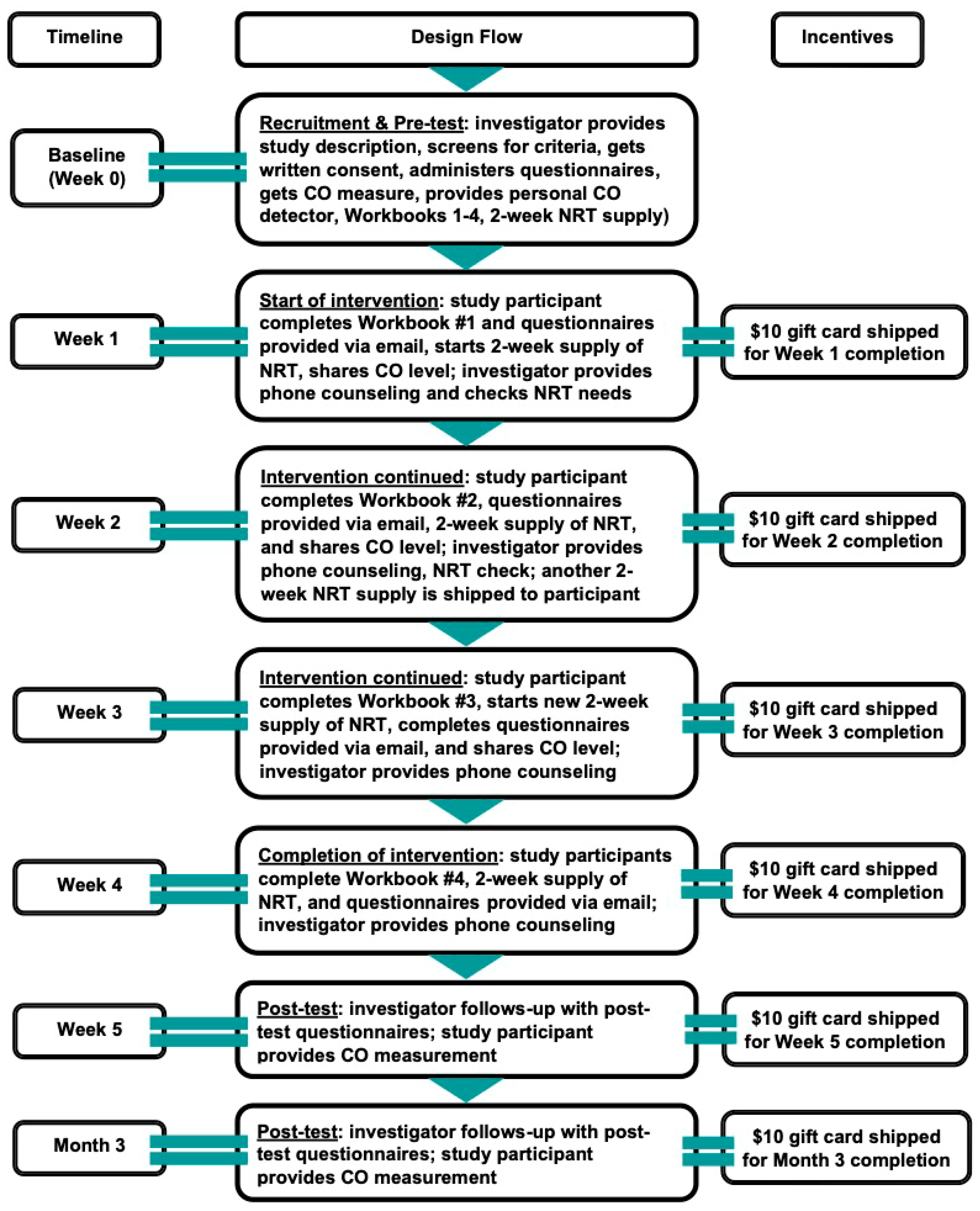

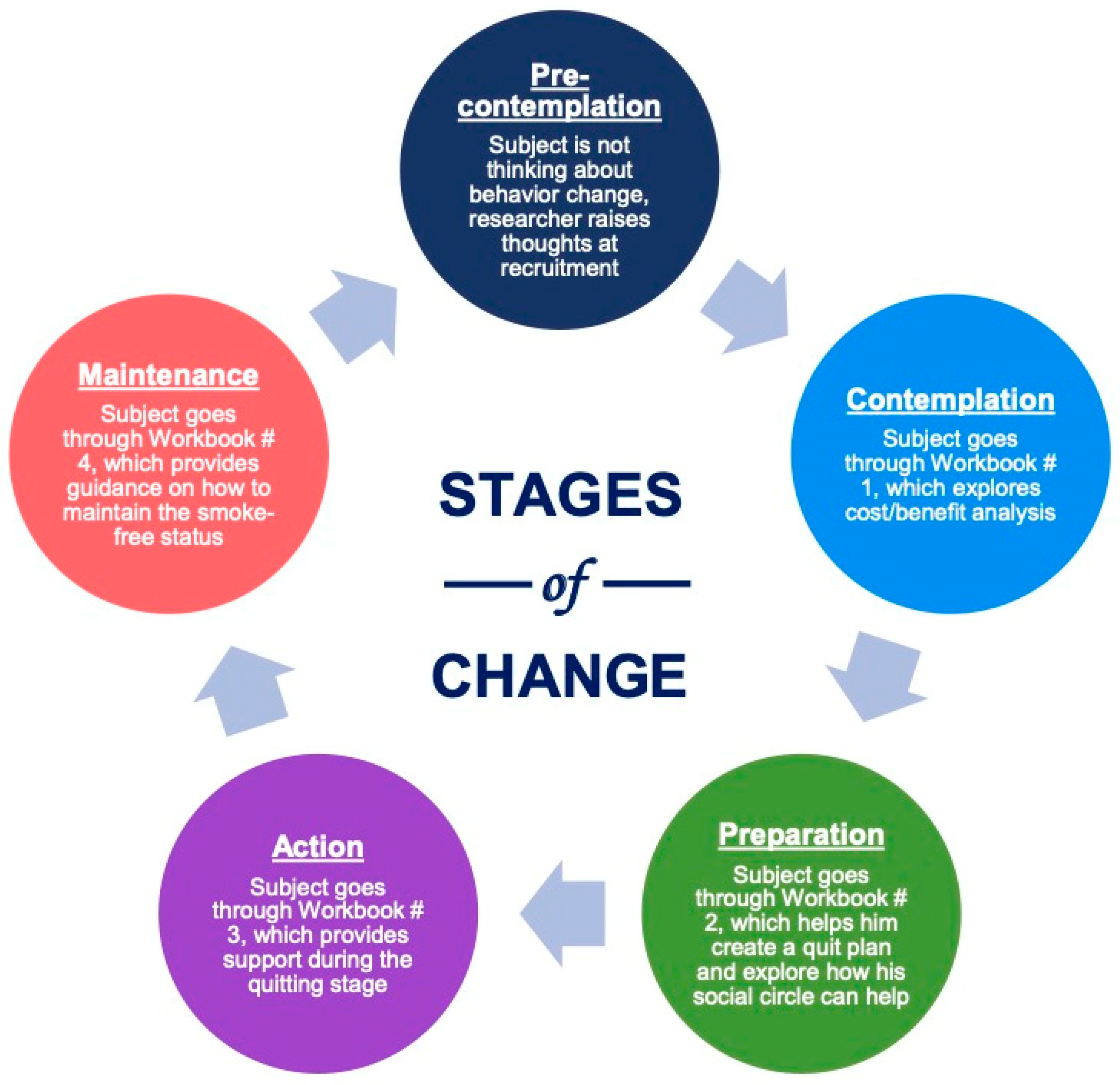

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Key Observations and Responses: Common Themes

3.1.1. Anxiety and Stress

- All participants expressed significant anxiety and stress related to delaying their first-morning cigarette. This suggests that the habitual nature of morning smoking might be a strong psychological barrier to cessation.

- Managing stress and anxiety could be a central focus of the intervention, possibly through relaxation techniques or adjusting the approach to reducing morning cravings.

3.1.2. Relapse

- All cases experienced relapse, which is common in smoking cessation. The challenge of complete cessation is evident, as participants reduced consumption but could not quit entirely.

3.1.3. Fagerström Test Scores

- The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence is a helpful indicator of addiction severity, and the scores indicate varying levels of dependence. While most participants showed a slight reduction in their scores, full cessation did not occur, even in individuals with high nicotine dependence (score 6/6).

3.1.4. Telephone MI Counseling

- MI over the phone seemed to help reduce anxiety and stress, but it was not enough to achieve complete cessation. This could point to the need for a more tailored approach, perhaps focusing on building self-efficacy, addressing triggers, and offering more intensive support.

3.1.5. Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale

- Lower withdrawal symptoms in some participants (e.g., Cases 1, 2, and 3) may indicate that nicotine dependence is not the only factor contributing to relapse. Case 4, however, showed high withdrawal symptoms, suggesting that physical cravings could have been a more significant barrier for this participant.

3.1.6. Fear of Counseling

- A key issue for some participants was fear regarding the counseling calls, especially in the first weeks. This could indicate a need for more reassurance and more explicit expectations regarding the process of cessation counseling.

3.2. Recommendations for Improvement

3.2.1. Addressing Anxiety and Stress

- Specific strategies targeting morning cravings and anxiety could improve outcomes. This might include mindfulness practices, behavioral strategies to delay the first cigarette, or exploring other ways to manage stress (e.g., exercise, breathing exercises).

3.2.2. Counseling Approach

- To overcome the fear of counseling, it may be helpful to provide more detailed information about what the sessions will involve, ensuring participants understand the collaborative nature of MI and that it is not a judgmental process.

3.2.3. Follow-Up and Continued Support

- The telephone MI counseling sessions seemed to help reduce stress, but were not sufficient for complete cessation. A more long-term approach, with more frequent check-ins or additional resources (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy), could be more effective in achieving full smoking cessation.

3.2.4. Customization of the Approach

- Tailoring the counseling approach based on the individual’s level of nicotine dependence (Fagerström score) and specific anxiety and stress triggers could lead to more effective outcomes. For example, Case 4 (with higher withdrawal symptoms) might benefit from a more intense focus on managing cravings.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ArA | Arab American(s) |

| Ex CO | Exhaled Carbon Monoxide |

| MI | Motivational Interviewing |

| NRT | Nicotine Replacement Therapy |

| TC | Telephone Counseling |

| TTM | Transtheoretical Model |

References

- Haddad, L.; El-Shahawy, O.; Shishani, K.; Madanat, H.; Alzyoud, S. Cigarette use attitudes and effects of acculturation among Arab immigrants in USA: A preliminary study. Health 2012, 4, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab American Institute. National Arab American Demographics; Arab American Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.aaiusa.org/demographics#:~:text=We%20estimate%20there%20are%203.7%20million%20Arab%20Americans.&text=Their%20Arab%20heritage%20reflects%20a,in%20the%20U.S.%20are%20citizens (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Kindratt, T.B.; Dallo, F.J.; Roddy, J. Cigarette Smoking Among US- and Foreign-Born European and Arab American Non-Hispanic White Men and Women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 5, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atrooz, F.; Asfar, T.; Oluwole, O.; Garey, L.; Salim, S.; Zvolensky, M. Insights into Cigarette and Waterpipe Use Among Houston-Based Arab Immigrants and Refugees. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziak, W.; Nakkash, R.; Bahelah, R.; Husseini, A.; Fanous, N.; Eissenberg, T. Tobacco in the Arab world: Old and new epidemics amidst policy paralysis. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 29, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bird, Y.; Forbeteh, K.; Nwankwo, C.; Moraros, J. Ethno-specific preferences of cigarette smoking and smoking initiation among Canadian immigrants—A multi-level analysis. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.; Nassar-McMillan, S.; Lambert, R.; Wang, Y.; Ager, J.; Arnetz, B. Pre- and post-displacement stressors and time of migration as related to self-rated health among Iraqi immigrants and refugees in southeast Michigan. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2010, 26, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirallah, K.A.; Cobb, C.O.; Alsulaiman, J.W.; Alzoubi, A.; Hoetger, C.; Kliewer, W.; Mzayek, F. Trauma exposure, mental health and tobacco use among vulnerable Syrian refugee youth in Jordan. J. Public Health 2020, 42, e343–e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.G.; Al-Bashaireh, A.M.; Ferrell, A.V.; Ghadban, R. Effectiveness of a culturally-tailored smoking cessation intervention for Arab-American men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update; Clinical Practice Guideline; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Prochaska, J.; Norcross, J. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.M.; Galea, S. The health of Arab-Americans living in the United States: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.H.; Stretch, V.; Balabanis, M.; Rosbrook, B.; Sadler, G.; Pierce, J.P. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: Effects of single session and multiple-session interventions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, N.; Bolman, C.; Lechner, L.; Mudde, A.; Verheugt, F.W.A.; de Vries, H. Effectiveness of two intensive treatment methods for smoking cessation and relapse prevention in patients with coronary heart disease: Study protocol and baseline description. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2012, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Corcoran, J. Culturally tailored smoking cessation for Arab American male smokers in community settings: A pilot study. Tob. Use Insights 2013, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.G.; Petro-Nustas, W. Predictors of intention to quit smoking among Jordanian university students. Can. J. Public Health 2006, 97, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerström, K.O. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A Revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerstrom, K.O.; Schneider, N.G. Measuring nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J. Behav. Med. 1989, 12, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiClemente, C.C.; Carbonari, J.P.; Montgomery, R.P.; Hughes, S.O. The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Stud. Alcohol 1994, 55, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, M.L.; Broome, K.M.; Knight, K.; Simpson, D.D. Measuring self-efficacy among drug-involved probationers. Psychol. Rep. 2000, 86, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicer, W.F.; Diclemente, C.C.; Rossi, J.S.; Prochaska, J.O. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: An integrative model. Addict. Behav. 1990, 15, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; West, R.; Gilbert, D. Recommendation for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004, 6, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becona, E.; Miguez, M.C. Concordance of self-reported abstinence and measurement of expired air carbon monoxide in a self-help smoking cessation treatment. Psychol. Rep. 2006, 99, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coultas, D.B.; Howard, C.A.; Peake, G.T.; Skipper, B.J.; Samet, J.M. Discrepancies between self-reported and validated cigarette smoking in a community survey of New Mexico Hispanics. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1988, 137, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, V.H.; Weglicki, L.S.; Templin, T.; Jamil, H.; Hammad, A. Intervention effects on tobacco use in Arab and non-Arab American adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2010, 35, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.P.; Salam, L.; Abdelhalim, G.; Lipton, R.; Myers, M.; Alnahari, S.; Hamud-Ahmed, W. Tobacco use, quitting, and service access for Northern California Arab Americans: A participatory study. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2023, 17, 379–392. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/907962 (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Description |

|---|---|

| Smoking reduction and cessation | The number of cigarettes and/or puffs smoked within the past 7 days. |

| Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine [19,20] | A standard instrument for assessing intensity of physical addiction to nicotine. The test was designed to provide an ordinal measure of nicotine dependence related to cigarette smoking. |

| The Perceived Self-Efficacy/Temptation Scale [21,22,23] | This scale is a 9-item self-efficacy scale commonly used to measure a participant’s confidence in his ability to abstain from cigarette smoking in a variety of different situations. |

| Exhaled Carbon Monoxide Test [25,26] | Carbon Monoxide biochemical marker was used to validate self-reported smoking cessation and reduction. Carbon monoxide (CO) concentration in parts per million (ppm) from expired breath will be measured using the Smokerlyzer meter. |

| Minnesota Tobacco Withdrawal Scale [24] | Features two separate measures for examining the severity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms in a subject: a self-report scale and an observer scale. The observer scale asks the scale-taker to rate the severity of four symptoms in someone they know who is experiencing nicotine withdrawal: “angry/irritable/frustrated,” “anxious/tense,” “depressed,” and “restless/impatient.” The self-report version asks for rankings of the severity of those same four symptoms, plus eleven others that cannot be observed by outsiders (including things as “desire or craving to smoke,” “insomnia, sleep problems, awakening at night,” or “dizziness”). Both scales use a Likert-type scale for the severity ratings, ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“severe”). |

| Case Number | Age | Cigarettes per Day | Ex CO (PMM) | Fagerstrom Test | MNWS | Challenges | Key Observations and Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | 10 10 after 28 days | 10 10 after 28 days | 6/6 (Baseline) 5/6 (after 28 days) | Low | 1. High anxiety/stress if postponing first-morning cigarette. 2. Relapse. 3. Fear of counseling in first 4 weeks. | 1. Reduction in cigarettes was achieved, but quitting was not successful. 2. Anxiety during morning delayed adherence. 3. Fear of early counseling calls reduced engagement. |

| 2 | 58 | 10–15 10–12 after 28 days | 12 12 after 28 days | 5/6 (Baseline) 4/6 (after 28 days) | Low | 1. Anxiety and Stress from delaying the first-morning cigarette. 2. Relapse. 3. Fear Related to counseling calls in the first 2 weeks. | 1. Reduction in cigarettes was achieved, but quitting was not successful. 2. Anxiety related to morning cigarette delay was a barrier to progress. 3. Participant's fear of counseling calls may have interfered with his engagement in the process. |

| 3 | 28 | 10 10 (after 28 days) | Unknown (presumably 10 based on similar cases) | 6/6 (Baseline) 5/6 (after 28 days) | Low | 1. Anxiety and Stress from delaying the first-morning cigarette. 2. Relapse. | 1. Reduction in cigarettes was achieved, but quitting was not successful. 2. Anxiety related to morning cigarette delay was a barrier to progress. 3. There was no indication of significant difference in counseling engagement compared to the other cases. |

| 4 | 30 | 15–20 15–20 (after 28 days) | Missing 10 (after 28 days) | 6/6 (Baseline) 5/6 (after 28 days) | High | Anxiety and Stress from delaying the first-morning cigarette. | 1. Reduction in cigarettes was achieved, but quitting was not successful. 2. High withdrawal symptoms may have made cessation more difficult. 3. Similar anxiety issues to other participants, possibly contributing to more difficulty in quitting. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Hajj, D.; Haddad, L.; Ferrell, A. Replication of a Culturally Tailored Tobacco Cessation Intervention for Arab American Men in North Carolina: An Exploratory Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091453

El Hajj D, Haddad L, Ferrell A. Replication of a Culturally Tailored Tobacco Cessation Intervention for Arab American Men in North Carolina: An Exploratory Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091453

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Hajj, Dana, Linda Haddad, and Anastasiya Ferrell. 2025. "Replication of a Culturally Tailored Tobacco Cessation Intervention for Arab American Men in North Carolina: An Exploratory Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091453

APA StyleEl Hajj, D., Haddad, L., & Ferrell, A. (2025). Replication of a Culturally Tailored Tobacco Cessation Intervention for Arab American Men in North Carolina: An Exploratory Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091453