Systematic Literature Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

3. Results

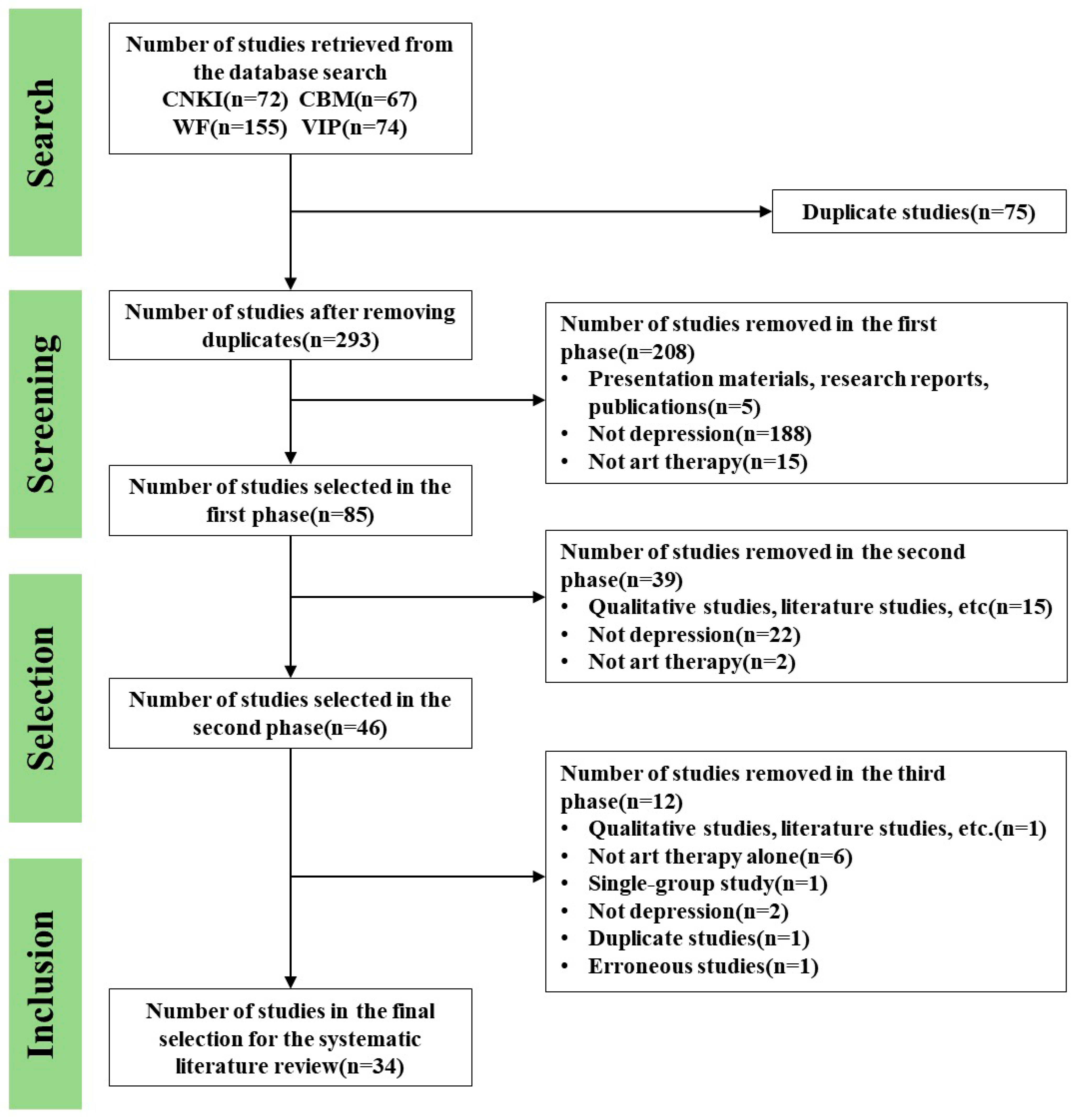

3.1. Results of the Literature Search

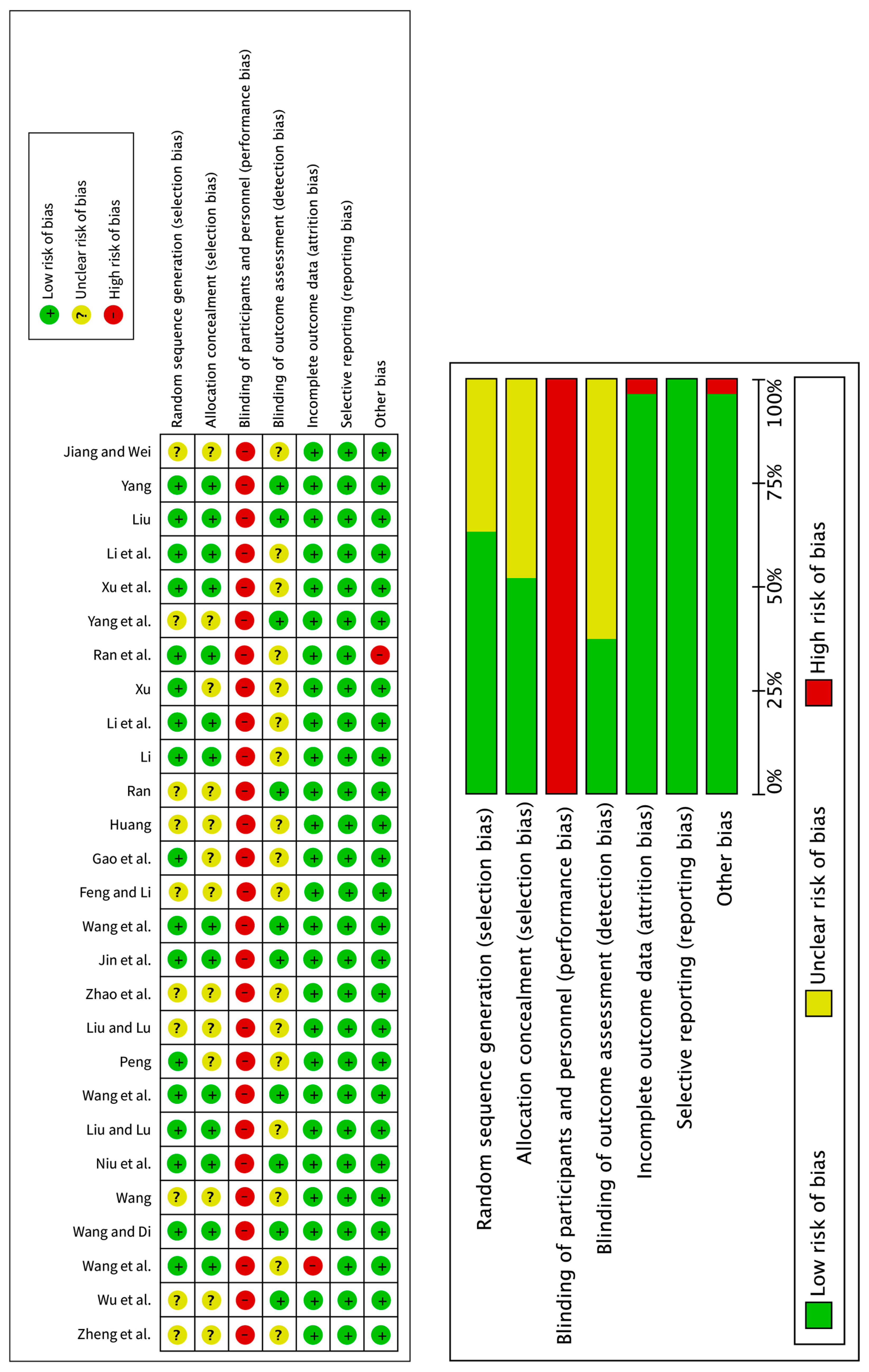

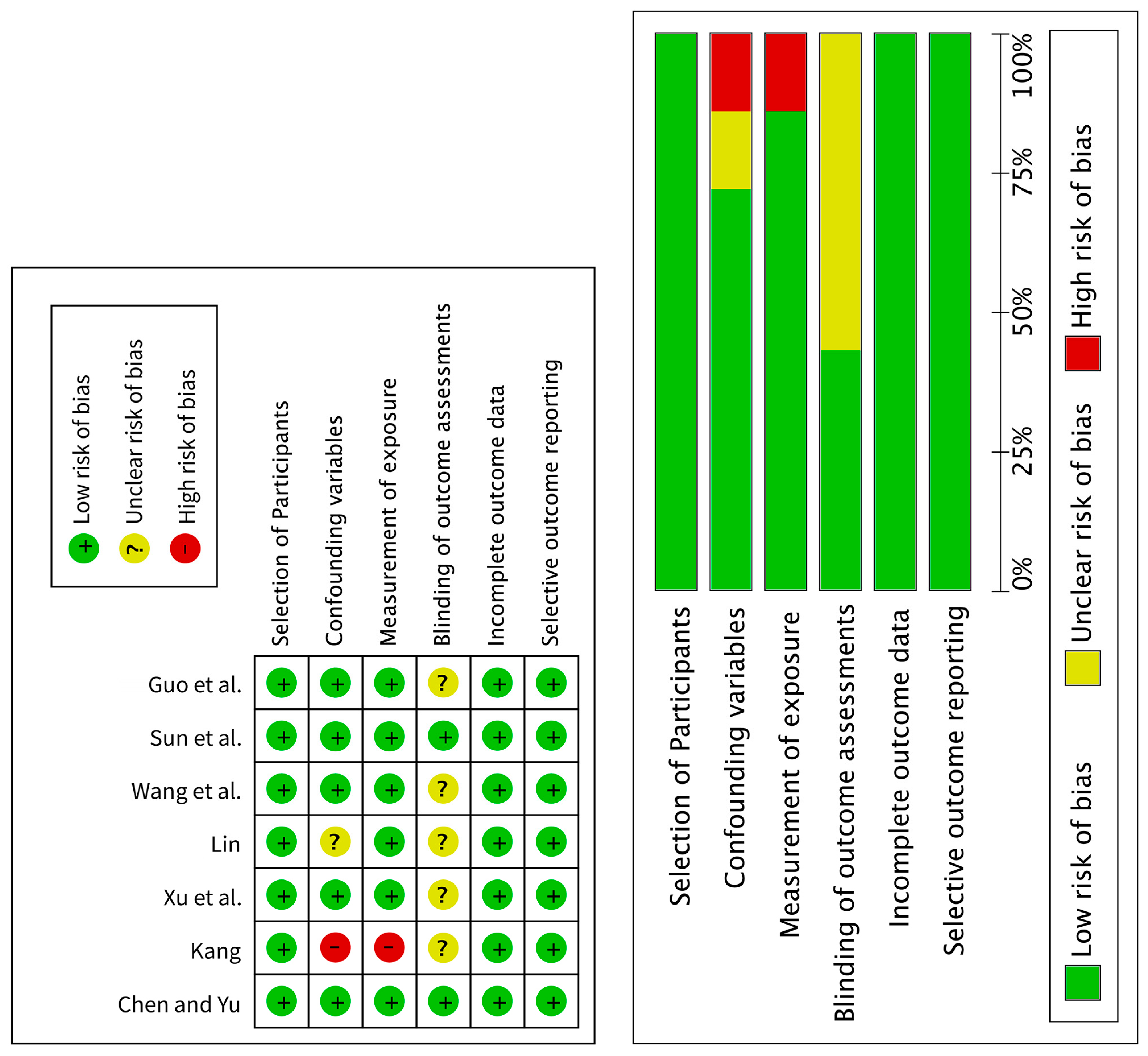

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment Results

3.3. Trends in Art Therapy Research for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder

3.4. Effects of Art Therapy Interventions for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends in Art Therapy Research for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder

4.2. Effects of Art Therapy Interventions for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- World Health Organization. Depressive Disorder (Depression). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Lu, J.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, C.; Xu, G.; Yin, H.; Xu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates (No. WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2). 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Qu, W.; Gu, S.S. New progress in research on depression treatment. J. Third Mil. Med. Univ. 2014, 36, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.M.; Li, B.M.; Zhang, D.Y.; Yuan, Z.X. Effectiveness of image painting group counseling intervention on recurrent depression in women and its impact on patients’ psychological stress response. Chin. J. Matern. Child Health 2023, 38, 3406–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission (NHC). Mental Disorders Diagnosis and Treatment Standards, 2020 Edition. General Office of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202012/a1c4397dbf504e1393b3d2f6c263d782.shtml (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Wang, C.F.; Duan, N.; Guo, Y.P. Evaluation of the effect of group drawing therapy combined with sertraline in the treatment of adolescent depression. Henan Med. Res. 2021, 30, 1453–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; van Straten, A.; Warmerdam, L.; Andersson, G. Psychological treatment of depression: A meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.R.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Q.; Song, Z.; Ding, Z.; Pang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: An epidemiological survey. Lancet 2009, 373, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. Study on the Effects of Cognitive Therapy Programs Using Art Activities. Master’s Thesis, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, R. The Magic of Art Therapy; Hak Ji Sa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, A. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Study on Experience of Art Therapy with Depressive Twentieth. Master’s Thesis, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Understanding on Lived Experience of Group Art Therapy for Adult Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Master’s Thesis, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wadeson, H.S. Art Psychotherapy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Choi, H.; Shin, J.; Suh, H.-S. The effects of adding art therapy to ongoing antidepressant treatment in moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerland, S.; Seiler, C.M. Role of systematic reviews and meta-analysis in evidence-based medicine. World J. Surg. 2005, 29, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.J. An introduction of the systematic review and meta-analysis. Hanyang Med. Rev. 2015, 35, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. Systematic Literature Review of the Treatment Effects of Art Therapy Media: Focusing on South Korean Group Art Therapy Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, CHA University, Pocheon, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rim, Y.A. Meta-analysis of the Effect of Art Therapy with the Elderly for Evidence-Based Social Work Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, Chosun University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.B. The effect of calligraphy therapy on depression. Chin. Minkang Med. 2008, 5, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, J.E.; Seo, H.J.; Seo, H.S.; Son, H.J.; Shin, C.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Chang, B.H. NECA’s Guidance for Undertaking Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Intervention; National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; Available online: https://www.neca.re.kr/lay1/program/S1T11C145/report/view.do?seq=21 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Wei, Y.J. The effects of group art therapy on self-esteem and cognitive function in adolescents with depressive disorder. Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database (Citation Version). Med. Health 2023, 7, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. An Intervention Study of Mandala Painting Therapy on Self-Esteem Level, Rumination Thinking in Adolescent Depressed Patients. Master’s Thesis, Dali University, Dali, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.H.; Mao, Y.D.; Fan, H.; Xiang, S.F.; Liu, L.B.; Ma, L.; Huang, C.M. Art therapy in depressed patients after stroke. Prev. Treat. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 23, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. A Systematic Review of Calligraphy Therapy: A Comparative Study of Korea and China. Ph.D. Thesis, Jeonju University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Dai, X.K.; Zeng, L. The effect of combined pharmacotherapy and art therapy on the rehabilitation outcomes of patients with depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 32, 147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.F.; Zhang, X.M.; Huang, X.X.; Chang, C.X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.P. Observation of the rehabilitation effects of mandala art therapy in patients with depressive disorder. Psychol. Mon. 2022, 17, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Z.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, Q.M. Effects of group manual activities on upper limb function and emotional state in depressed patients after stroke. Chin. Rehabil. 2022, 37, 298–300. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7107223191&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ran, M.L.; Wang, M.J.; Jiang, G.Q. Observations on the efficacy of sertraline combined with painting in the treatment of adolescent depression. China Pharm. 2021, 30, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F. The effect of art therapy on the rehabilitation of adolescents with depressive disorder. Reflexology Rehabil. Med. 2021, 2, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Su, J.N.; Lai, L.P.; Liu, Y. Effect of mandala painting training on the rehabilitation of patients with postpartum depression. China Contemp. Med. 2021, 28, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Analysis of the therapeutic effect of combined pharmacological and art therapy in adolescents with depressive disorder. China Pract. Med. 2021, 16, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.B. Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of combined pharmacological and art therapy in adolescents with depressive disorder. Smart Healthc. 2020, 6, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.L. The Effects of Group Art Therapy on Self-Concept and Executive Function in Adolescents with Depressive Episodes. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Effect of painting art treatment on higher vocational students with depressive symptoms. J. Huainan Vocat. Tech. Coll. 2020, 20, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.C.; Peng, F.; Luo, W.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the effect of combined pharmacotherapy and mandala painting therapy on depressive disorder. J. Chengdu Med. Coll. 2020, 15, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.F.; Li, J.H. Observation of the effects of group art therapy on self-esteem and cognition in adolescents with depression. Gen. Nurs. 2019, 17, 4155–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Dong, C.; Liu, D.J.; Wang, W. The effect of group art therapy on emotion and executive function in adolescents with depressive disorder. J. Hebei Med. Univ. 2019, 40, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, S.Y.; Chen, A.M. The effect of coloring activities on negative emotions in patients with depression. Chin. West. Med. Comb. Nurs. 2019, 5, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Q.; Wang, H.Q.; He, J.P.; Li, Q.; Lin, L.; Guan, Z.B.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J.Y. Intervention effect of art analysis and therapy on adolescent depressive disorder. China Med. Innov. 2019, 16, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Lu, J.W. The effect of group art therapy on emotional experiences in female patients with depression. Spec. Health 2019, 26, 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W. The Application Effect of Handicraft Work in the Rehabilitation of Depression. Health for everyone. 2019, 12, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Dong, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W. The effect of group art therapy on self-esteem and cognitive function in adolescents with depression. J. Hebei Med. Univ. 2018, 39, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.J.; He, J.P.; Wang, H.Q.; Song, Z.; Wei, Y.D. The effect of art analysis and therapy techniques in the treatment of adolescents with depression. Chin. J. Conval. Med. 2018, 27, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, J.W. Effect of mandala painting therapy on post-stroke depression. Nurs. Integr. Tradit. Chin. West. Med. 2018, 4, 116–118. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7000687489&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Kang, Y.M. Observation of the therapeutic effect of combined medication and art therapy in adolescents with depression. Chin. J. Pract. Med. 2018, 13, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.N.; Zhou, Y.P.; Liao, L.W.; Pan, G.H. The effect of group art therapy combined with sertraline on patients with first-episode depression. Neurodegener. Dis. Ment. Health 2016, 16, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.P. Analysis of the therapeutic effect of group art therapy on hospitalized patients with depression in a hospital in Shandong Province, China. Med. Soc. 2014, 27, 85–87. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4QAaWarC2DTpJx_JKLSEM1W9O_Kx5g8JYm_ib4fmlLku6tDCRrqwGT-7oNqGTWxZ-GSF84sP20gLWPXH6lrlHCBUITsIanE3_wZaHBQuE9-Yne3GbSQfCJu6NpPqFu4r3vCQ_V-UJaVr2XiCylgRtVlcaZ4JyYgMyBG1Hdzyf6TYaOb0MF-rNO9V3bTWDT8l&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Chen, X.C.; Yu, H.H. The effect of origami therapy on patients with depression. Hosp. Manag. Forum 2014, 5, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.X.; Di, X.L. The effect of cross-stitch art behavior therapy on social functioning of chronic hospitalized depressed patients. Chin. J. Mod. Nurs. 2012, 18, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Lei, J.P.; Zhang, A.H.; Ma, R.J.; Zhu, L. The application value of art therapy in the treatment of depression. Chin. J. Civ. Health Med. 2011, 23, 1974–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Y.; Nie, J.Y.; Ouyang, W.M.; Li, S.M. The effect of handicraft training on depression in patients after stroke. Chin. J. Rehabil. 2011, 26, 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y. Research Trends Analysis for Adolescent Depression in Art Therapy: Focusing on Master’s Theses in Korea from 2002 to 2021. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.T. Research on the problems and countermeasures of painting therapy in China. J. Heilongjiang Inst. Educ. 2012, 11, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Liu, W.Y. Analyzing the effectiveness of art therapy for psychiatric inpatients. Chin. Rehabil. 2003, 18, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G. An analysis of the role of folk art in artistic exchange within single-parent families. Forum Contemp. Educ. 2011, 34, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Research on the historical transmutation of art therapy and the strategy of promoting the cultivation of specialized talents in China. Art Educ. Res. 2020, 4, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y. Experimental Psychology; People’s Education Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Systematic Literature Review of the Effects of Art Therapy for Chinese Schizophrenia Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, Jeonju University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.L.; Yu, H.K.; Kim, H.K. A meta-analysis on the effect of art therapy programs for elementary school students. Korean J. Educ. Methodol. Stud. 2010, 22, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H. Analysis of Research Trends in Art Therapy for Female Depression Patients. Master’s Thesis, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.Y.; Lee, S.D. A meta-analysis of the program for children of multicultural families. Korean Assoc. Learn.-Centered Curric. Instr. 2019, 19, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, W. Systematic Literature Review of Group Art Therapy for South Korean University Students: Focusing on Korean Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, Jeonju University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, J.E.; Coleman, K.; Winner, E. Short-term mood repair through art: Effects of medium and strategy. Art Ther. 2011, 28, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. The development of art therapy: Review and prospect. J. East China Norm. Univ. 2014, 32, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.H.; Zheng, Y.W.; Yan, F.W. Effects of group drawing therapy on the emotional experience of female depressed patients. Spec. Health 2019, 26, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.J.; Cui, H.S.; Liu, M.L.; Wu, W.Y.; Zhao, X.D. Analysis of social functioning status and influencing factors in patients with first-episode and recurrent depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 26, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Chen, J.D. Drawing characteristics of life event stress in adolescents. Health J. Neurosci. Ment. Health 2014, 14, 28–30. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=49308093&from=Qikan_Search_Index (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Qiu, H.Z.; Liang, R.Q.; Cheng, L.Y.; Yi, C. Research progress on the role of painting therapy in psychological rehabilitation. China J. Health Psychol. 2015, 23, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G. The significance and application of the psychology of drawing in teaching art education. Art Educ. 2015, 8, 100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, C.; Law, J. Cognitive and physiological processes underlying drawing skills. Leonardo 1995, 28, 203–205. Available online: https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/607018 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 1 January 2008—31 December 2023 | All literature outside the inclusion period |

| Type of publication | Academic journal articles (published in China) Thesis (published in China) | Conference Papers Reportable papers or publications Seminar reviews or Supplementary Materials |

| Duplicate literature | Academic journal articles Recent years first | Duplicate publication of academic journal articles Thesis with the same content as the journal article |

| Subject of mediation | Depression patients Chinese | Patients who have not been diagnosed with depression Non-Chinese Family members or caregivers of patients with depression |

| Arbitration measures | Art therapy | Art therapy and other art therapies (music, dance, psychodrama, etc.) |

| Implementer | No special restrictions | - |

| Research design | Randomized controlled experiment Nonrandomized controlled experiment | Qualitative research (case study) Literature research (trend analysis, meta-analysis, etc.) Control group or individual study |

| Control group | Same period as the experimental group Observation and measurement without participating in art therapy | When the reference period is unclear or different from the experimental group Asynchronous observation and measurement |

| Experimental period | No special restrictions | - |

| Place of experiment | No special restrictions | - |

| Database | Search Formula |

|---|---|

| CNKI | (Subject: Painting Therapy) OR (Subject: Arts Therapy) OR (Subject: Art Therapy) AND (Subject: Depression + Depressed Patients); Restrictions: January 2007 to October 2023 |

| CBM | “Painting Therapy” [core field] OR “Arts Therapy” [core field] OR “= Art Therapy” [core field] AND “Depression” [core field]; Restrictions: 2007–2023; Case reports; Clinical experiment; Randomized controlled experiment; |

| WF | Subject: (“Painting Therapy”) or Subject: (“Arts Therapy”) and Subject: (Depression); Restriction: 2007–2023; |

| VIP | (Arbitrary field = Painting Therapy OR arbitrary field = Arts Therapy) OR arbitrary field = Art Therapy) AND arbitrary field = Depression); Restriction: 2007–2023; |

| ID | Author (Year) | Publication Type | N (EG/CG) | Gender (Male/Female) | Age (M ± SD) | Intervention Frequency | Activity Type | Activity Techniques | Measurement Instruments | Measurement Outcomes (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiang and Wei [25] ** | Research article | N = 100 (EG = 50/CG = 50) | EG: 7/43 CG: 8/42 | EG: 16.20 ± 1.40 CG: 15.84 ± 1.35 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | PANAS MCCB SES | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| 2 | Yang [26] ** | Research article | N = 46 (EG = 23/CG = 23) | EG: 6/17 CG: 5/18 | EG: 15.52 ± 0.387 CG: 14.96 ± 0.424 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 40–50 min/each | P + M | Painting | SDS SAS RSS SES | p < 0.001 p = 0.009 p < 0.005 p = 0.002 |

| 3 | Sun et al. [27] ** | Research article | N = 93 (EG = 48/CG = 45) | EG: 31/17 CG: 29/16 | EG: 62.51 ± 5.39 CG: 63.47 ± 5.22 | Total 5 times, 30–60 min/each | G + M | Painting Chinese painting | SDS SAS MoCA FSS | p < 0.01 p < 0.005 p < 0.01 p < 0.05 |

| 4 | Guo et al. [6] ** | Research article | N = 82 (EG = 42/CG = 40) | EG: 0/42 CG: 0/40 | EG: 46.07 ± 6.75 CG: 45.92 ± 6.71 | 8 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD ERQ RSS CFQ | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.05 |

| 5 | Liu [28] ** | Dissertation | N = 66 (EG = 33/CG = 33) | EG: 5/28 CG: 5/28 | EG: 14.55 ± 1.716 CG: 14.76 ± 1.601 | 8 weeks, 1 time/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD TAS-20 SES | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| 6 | Li et al. [29] * | Research article | N = 156 (EG = 78/CG = 78) | EG: 42/36 CG: 46/32 | EG: 38.9 ± 6.3 CG: 40.2 ± 7.2 | 8 weeks, 3 times/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Mandala painting Painting | HAMD HAMA NOSIE | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| 7 | Xu et al. [30] ** | Research article | N = 80 (EG = 40/CG = 40) | EG: 18/22 CG: 15/25 | EG: 42.30 ± 15.76 CG: 41.15 ± 16.94 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Mandala painting | SDS SAS SDSS RESE HHI | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| 8 | Yang et al. [31] ** | Research article | N = 58 (EG = 29/CG = 29) | EG: 15/14 CG: 14/15 | EG: 54.41 ± 7.61 CG: 53.32 ± 7.82 | 4 weeks, 5 times/week, 30 min/each | G + M | Paper crafts Sticking Knitting | HAMD MBI FMAS | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.05 |

| 9 | Ran et al. [32] * | Research article | N = 42 (EG = 22/CG = 20) | EG: 11/11 CG: 10/10 | EG: 13.38 ± 1.17 CG: 13.36 ± 1.27 | 8 weeks, 1 time/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Not recorded | DSRSC PHCSS TESS | p < 0.005 * p = 0.001 ** p = 0.87 |

| 10 | Wang et al. [8] ** | Research article | N = 98 (EG = 49/CG = 49) | EG: 21/28 CG: 23/26 | EG: 18.67 ± 1.34 CG: 18.39 ± 1.16 | 4 weeks, 5 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | BDI BAI SDSS | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.05 |

| 11 | Xu [33] ** | Research article | N = 96 (EG = 48/CG = 48) | EG: 27/21 CG: 26/22 | EG: 18.11 ± 1.55 CG: 18.03 ± 1.56 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 80 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD HAM NOSIE | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.05 |

| 12 | Li et al. [34] ** | Research article | N = 80 (EG = 40/CG = 40) | EG: 0/40 CG: 0/40 | EG: 28.56 ± 5.72 CG: 27.79 ± 5.14 | Total 8 weeks, | G + M | Mandala painting | HAMD SAS GWB | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.001 |

| 13 | Li [35] * | Research article | N = 86 (EG = 43/CG = 43) | EG: 23/20 CG: 22/21 | EG: 16.48 ± 2.16 CG: 16.26 ± 2.02 | 24 weeks, 1 time/week, 50 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD GQOLI | p < 0.001 p < 0.05 |

| 14 | Lin [36] * | Research article | N = 40 (EG = 20/CG = 20) | EG: 10/10 CG: 10/10 | EG: 15.66 ± 1.55 CG: 16.55 ± 1.65 | 24 weeks, 1 time/week, 50 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD | p < 0.05 |

| 15 | Ran [37] * | Dissertation | N = 34 (EG = 17/CG = 17) | EG: 9/8 CG: 7/10 | EG: 12.58 ± 1.17 CG: 12.58 ± 1.41 | 8 weeks, 1 time/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | DSRSC SCARED WCST PHCSS | p < 0.001 * p < 0.001 ** p = 0.08 p < 0.001 |

| 16 | Huang [38] * | Research article | N = 80 (EG = 40/CG = 40) | EG: 22/18 CG: 21/19 | EG: 16–21 CG: 17–21 | 12 weeks, 1 time/week, 30–60 min/each | G + M | Painting | SDS | p < 0.05 |

| 17 | Gao et al. [39] ** | Research article | N = 78 (EG = 39/CG = 39) | EG: 16/23 CG: 14/25 | EG: 39.00 ± 12.91 CG: 45.00 ± 16.57 | 4 weeks, 3 times/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Mandala painting Painting | HAMD HAMA NOSIE | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 * p < 0.001 |

| 18 | Feng and Li [40] * | Research article | N = 90 (EG = 45/CG = 45) | EG: 24/21 CG: 23/22 | EG: 16.10 ± 4.1 CG: 16.30 ± 4.1 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | PANAS MCCB SES | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

| 19 | Wang et al. [41] * | Research article | N = 53 (EG = 25/CG = 28) | EG: 12/13 CG: 12/16 | EG: 17.96 ± 3.71 CG: 18.21 ± 2.83 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting Clay Mandala painting | PANAS WCST | p < 0.05 ** p = 0.08 |

| 20 | Jin et al. [42] * | Research article | N = 71 (EG = 36/CG = 35) | EG: 16/20 CG: 14/21 | EG: 34.58 ± 8.81 CG: 32.06 ± 8.46 | 4 weeks, 3 times/week, 30 min/each | G + M | Coloring | HAMD HAMA NOSIE | p = 0.034 p < 0.001 NOSIE |

| 21 | Zhao et al. [43] * | Research article | N = 100 (EG = 50/CG = 50) | 48/52 | All: 20.30 ± 4.60 | 12 weeks, 1 time/week, 40 min/each | G + M | Painting Collage | SDS SAS SDSS WHOQOL | p < 0.001 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 * p < 0.001 |

| 22 | Liu and Lu [44] ** | Research article | N = 62 (EG = 30/CG = 32) | EG: 0/30 CG: 0/32 | EG: 32.77 ± 10.15 CG: 33.44 ± 13.97 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | SDS PANAS | p < 0.05 p < 0.001 |

| 23 | Peng [45] * | Research article | N = 60 (EG = 30/CG = 30) | EG: 11/19 CG: 10/20 | EG: 51.1 ± 6.20 CG: 50.9 ± 5.80 | 2 weeks, 7 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Paper crafts Sticking Origami | HAMD MMSE | p < 0.05 p < 0.005 |

| 24 | Wang et al. [46] * | Research article | N = 53 (EG = 25/CG = 28) | 24/29 | EG: 17.96 ± 3.71 CG: 18.21 ± 2.83 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting Clay Mandala painting | MCCB SES | ** p = 0.332 p < 0.001 |

| 25 | Xu et al. [47] * | Research article | N = 70 (EG = 35/CG = 35) | EG: 19/16 CG: 17/18 | EG: 23.1 ± 3.60 CG: 23.8 ± 3.90 | 12 weeks, 1 time/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Painting Collage | SDS Observation of adverse effects | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 |

| 26 | Liu and Lu [48] ** | Research article | N = 60 (EG = 30/CG = 30) | 36/24 | All: 45–80 | 8 weeks, 3 times/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Painting Mandala painting | HAMD HAMA | p < 0.01 p < 0.01 |

| 27 | Kang [49] * | Research article | N = 36 (EG = 18/CG = 18) | EG: 10/8 CG: 10/8 | EG: 16.75 ± 2.12 CG: 17.73 ± 1.05 | 24 weeks, NR | G + M | Not recorded | HAMD HAMA | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 |

| 28 | Niu et al. [50] * | Research article | N = 60 (EG = 30/CG = 30) | EG: 14/16 CG: 13/17 | EG: 34.1 ± 7.80 CG: 34.5 ± 7.10 | 4 weeks, 5 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | HAMD Observation of adverse effects | p = 0.04 ** p > 0.05 |

| 29 | Wang [51] * | Research article | N = 36 (EG = 18/CG = 18) | 14/22 | All: 46.78 ± 11.93 | 4 weeks, 2 times/week, 90 min/each | G + M | Painting | SDS Self-reported scale of group membership | p = 0.002 p < 0.001 |

| 30 | Chen and Yu [52] ** | Research article | N = 64 (EG = 32/CG = 32) | 23/41 | All: 18–56 | 4 weeks, 1 time/week, 75 min/each | G + M | Origami | HAMD | p < 0.01 |

| 31 | Wang and Di [53] ** | Research article | N = 64 (EG = 32/CG = 32) | 0/64 | All: 48.0 ± 6.0 | 12 weeks, 7 times/week, 120 min/each | G + M | Knitting | SSPI NOSIE | p < 0.01 * p < 0.05 |

| 32 | Wang et al. [54] * | Research article | N = 59 (EG = 30/CG = 29) | EG: 14/16 CG: 13/16 | NR | 12 weeks, 3 times/week, 120 min/each | G + M | Drawing Painting | SDSS GQOLI-74 | p < 0.001 * p < 0.001 |

| 33 | Wu et al. [55] ** | Research article | N = 60 (EG = 30/CG = 30) | EG: 18/12 CG: 20/10 | EG: 49.9 ± 6.30 CG: 49.7 ± 7.50 | 24 weeks, 7 times/week, 60 min/each | G + M | Knitting Paper crafts Sticking | HAMD BI MMSE | * p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.005 |

| 34 | Zheng et al. [22] * | Research article | N = 61 (EG = 31/CG = 30) | EG: 12/19 CG: 10/20 | EG: 37.5 ± 12.50 CG: 36.6 ± 12.80 | 24 weeks, 2–3 times/week, 120 min/each | G + M | Calligraphy | HAMD HAMA | p < 0.01 p < 0.01 |

| Category | Risk of Bias | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random sequence generation | Low | 17 | 63.0 |

| Uncertain | 10 | 37.0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Allocation concealment | Low | 14 | 51.9 |

| Uncertain | 13 | 48.1 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Low | 0 | 0 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 27 | 100 | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Low | 10 | 37.0 |

| Uncertain | 17 | 63.0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | 26 | 96.3 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 1 | 3.7 | |

| Selective reporting | Low | 27 | 100 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Other bias | Low | 26 | 96.3 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 1 | 3.7 |

| Category | Classification | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection of participants | Low | 7 | 100 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 37.0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Confounding variables | Low | 5 | 71.0 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 14.3 | |

| High | 1 | 14.3 | |

| Measurement of exposure | Low | 6 | 85.7 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 1 | 14.3 | |

| Blinding for outcome assessment | Low | 3 | 42.9 |

| Uncertain | 4 | 57.1 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | 7 | 100 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Selective outcome reporting | Low | 7 | 100 |

| Uncertain | 0 | 0 | |

| High | 0 | 0 |

| Classification (N) | Result |

|---|---|

| Research Features | Research on patients with depression began in 2008 and has been increasing, with most of the results published in academic journals (31 papers, 91.2%) |

| Subject of mediation | Mainly general depression patients with an average age in their 20 s (13 cases, 38.2%) |

| Mediation Methods | In most studies, the total number of participants was up to 70 (21 studies, 61.7%), the number of interventions was 6 to 15 (20 studies, 58.8%), the duration of each intervention was 60 to 90 min (23 studies, 67.6%), and group therapy was used (32 studies, 94.1%). |

| Contents of arbitration | Among various art therapy techniques, many studies utilized painting techniques (23 items, 46.9%). |

| Classification (N) | Specific Variable (N) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional domain (31) | Depression (28), Anxiety (14), Positive and Negative Emotions (4), Inability to express Emotions (1), Emotional regulation (1), Happiness (1) | Nearly all of the studies investigating emotional factors reported positive effects. However, Wu et al. (2011) found no significant changes in factors reflecting depressive mood—specifically body weight, diurnal variation, and sleep disturbances—with all p values > 0.05, though significant differences were observed in other factors [55]. Similarly, Ran reported no significant difference in the generalized anxiety factor (p > 0.05), while significant differences were identified in all other factors measured [37]. |

| Social do-main (12) | Social functioning (5), mental and so-cial functioning (5), quality of life (3), activities of daily living (2) | Majority of the studies investigating social factors reported positive effects. However, Wang and Di (2012) found no significant difference in personal hygiene (p > 0.05), although significant differences were observed in all other factors [53]. |

| Cognitive Domain (10) | Cognitive function (6), rumination (2), mental state (2), cognitive integration (1) | All studies investigating cognitive factors reported positive effects. |

| Self Domain (9) | Self-esteem (5), self-awareness (2), self-efficacy (1), self-evaluation (1), sense of hope (1) | All studies examining self-related factors reported positive outcomes. |

| Physical Domain (5) | Adverse reactions (3), fatigue (1), mo-tor function; upper limb (1) | Among studies examining physical indicators, three reported posi-tive effects. However, Niu et al. and Ran et al. found no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions compared to the con-trol group (p > 0.05) [32,50]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, G.; Park, B.R.; Kim, B.H. Systematic Literature Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091443

Xu G, Park BR, Kim BH. Systematic Literature Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091443

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Guochao, Bo Ram Park, and Bo Hyun Kim. 2025. "Systematic Literature Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091443

APA StyleXu, G., Park, B. R., & Kim, B. H. (2025). Systematic Literature Review of Research on the Effectiveness of Art Therapy for Chinese Patients with Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091443