Exploring the Relation Between Nursing Workload and Moral Distress, Burnout, and Turnover in Latvian Intensive Care Units: An Ecological Analysis of Parallel Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Respondents

- MMD-HP (Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals): 27 items, two dimensions (frequency and intensity), 5-point Likert scales, total scores 0–216; higher scores indicate more frequent and intense moral distress. Cronbach’s α in this study: 0.938 (frequency), 0.976 (intensity) [30].

- Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI): 19 items in three subscales (personal-, work-, and client-related burnout), 5-point Likert scale; higher scores indicate greater burnout. Cronbach’s α = 0.928 overall [31].

- Anticipated Turnover Scale (ATS): 12 items measuring intention to leave one’s job, 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate stronger turnover intentions. In this study, Cronbach’s α = 0.342, suggesting multidimensionality; results are interpreted with caution [32].

2.3. Staff Shortage Calculation

2.4. Data Processing and Statistics

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Nursing Workload in ICUs

3.2. Psycho-Emotional Stress and Staff Turnover Intentions

3.2.1. Moral Distress Results

- 1.

- Question No. 5: continuation of aggressive treatment when the patient’s death is highly probable (M = 2.35);

- 2.

- Question No. 16: obligation to care for more patients than is safely possible (M = 2.18);

- 3.

- Question No. 19: excessive documentation requirements that compromise the quality of care (M = 2.26).

- 1.

- Question No. 16: insufficient staff—too many patients per nurse (M = 2.63);

- 2.

- Question No. 8: participation in care that causes unnecessary suffering (M = 2.52);

- 3.

- Questions No. 5, 9, 14: related to aggressive treatment, lack of continuity of care, and poor team communication conditions (all M > 2.4).

3.2.2. Copenhagen Burnout Inventory Results

3.2.3. Potential Staff Turnover

3.2.4. Results of Correlation and Regression Analysis

3.3. Organizational-Level Comparison Between Structural Stress and Psycho-Emotional State

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| ICU | Intensive Care Units |

| NAS | The Nursing Activities Score |

| r | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| USA | United States of America |

| TISS-28 | Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System—28 items |

| MMD-HP | Moral Distress Scale for Healthcare Professionals |

| CBI | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory |

| ATS | Anticipated Turnover Scale |

| IBM SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| PĒK | Pētījuma Ētikas komitēja |

| D | Day |

| N | Night |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| min | Minimum |

| max | Maximum |

| M | Mean |

| PRB | Personal-related burnout |

| WRB | Work-related burnout |

| CRB | Client-related burnout |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- European Commission. State of Health in the EU: Latvia—Country Health Profile 2021; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-12/2021_chp_lv_english.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- OECD. Nurses (Indicator). OECD Data. 2023. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/healthres/nurses.htm (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- National Health Service of Latvia (NVD). Statistikas Pārskats Par Ārstniecības Personām un Ārstniecības Atbalsta Personām uz 2023. Gada 31. Decembri. Nacionālais Veselības Dienests, Rīga. 2024. Available online: https://www.vmnvd.gov.lv/sites/vmnvd/files/data_content/58b57889c736b1.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Arteaga, G.; Bacu, L.; Moreno Franco, P. Patient Safety in the Critical Care Setting: Common Risks and Review of Evidence-Based Mitigation Strategies. In Contemporary Topics in Patient Safety—Volume 2; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, J.N.; Kahn, J.M.; Cohen, T.R.; Weingart, L.R. Teamwork in the Intensive Care Unit. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Millere, I.; Trups-Kalne, I. Adaptation of the Nursing Activities Score in Latvia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoud, F.; Rezaei, M.; Asgarian, F.S.; Rassouli, M. Workload and Quality of Nursing Care: The Mediating Role of Implicit Rationing of Nursing Care, Job Satisfaction and Emotional Exhaustion by Using Structural Equations Modeling Approach. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.; Willis, K.; Smallwood, N. The Collective Experience of Moral Distress: A Qualitative Analysis of Perspectives of Frontline Health Workers during COVID-19. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2025, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.-S.; Kim, B.-J. “The Power of a Firm’s Benevolent Act”: The Influence of Work Overload on Turnover Intention, the Mediating Role of Meaningfulness of Work and the Moderating Effect of CSR Activities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, M.G. Nursing Workload: A Concept Analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvé-Udina, M.E.; González-Samartino, M.; López-Jiménez, M.M.; Planas-Canals, M.; Rodríguez-Fernández, H.; Batuecas Duelt, I.J.; Tapia-Pérez, M.; Pons Prats, M.; Jiménez-Martínez, E.; Barberà Llorca, M.À.; et al. Acuity, nurse staffing and workforce, missed care and patient outcomes: A cluster-unit-level descriptive comparison. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 2216–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalisch, B.J.; Landstrom, G.L.; Hinshaw, A.S. Missed nursing care: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lief, L.; Berlin, D.A.; Maciejewski, R.C.; Westman, L.; Su, A.; Cooper, Z.R.; Ouyang, D.J.; Epping, G.; Derry, H.; Russell, D.; et al. Dying Patient and Family Contributions to Nurse Distress in the ICU. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzian, A.H.; Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A.; Sharif-Nia, H.; Farhadi, B.; Navab, E. Exploring the Concept and Management Strategies of Caring Stress among Clinical Nurses: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1337938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, G.; Ives, J.; Bradbury-Jones, C.; Irvine, F. What Is ‘Moral Distress’? A Narrative Synthesis of the Literature. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez, A.; Borrego, Y.; Alcalde, F.J.; Durán, A. Moral Distress and Emotional Exhaustion in Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrowes, S.A.B.; Casey, S.M.; Pierre-Joseph, N.; Talbot, S.G.; Hall, T.; Christian-Brathwaite, N.; Del-Carmen, M.; Garofalo, C.; Lundberg, B.; Mehta, P.K.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on Mental Health, Burnout, and Longevity in the Workplace among Healthcare Workers: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2023, 32, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, K.; Guttormson, J.; McAndrew, N.S.; Losurdo, H.; Loonsfoot, D.; Schmitz, S.; Fitzgerald, J. The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Intensive Care Nurses’ Personal and Professional Well-Being: A Qualitative Study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 76, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.-W.; Hu, F.-H.; Jia, Y.-J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, W.-Q.; Zhao, D.-Y.; Shen, W.-Q.; Chen, H.-L. COVID-19 Pandemic Increases the Occurrence of Nursing Burnout Syndrome: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Preliminary Data from 38 Countries. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 69, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, K.S.; Simms-Ellis, R.; Grange, A.; Griffiths, M.E.; Coleman, R.; Harrison, R.; Shearman, N.; Horsfield, C.; Budworth, L.; Marran, J.; et al. Critical Care Nursing Workforce in Crisis: A Discussion Paper Examining Contributing Factors, the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Potential Solutions. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 7125–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, R.T.N.; Blackman, C.; Gauthier, M.; Fan, E.; Fowler, R.; Johnston, C.; Jeremy Katulka, R.; Marcushamer, S.; Menon, K.; Miller, T.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: The Impact on Canada’s Intensive Care Units. FACETS 2022, 7, 1411–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmolin, G.D.L.; Lunardi, V.L.; Lunardi, G.L.; Barlem, E.L.D.; Silveira, R.S.D. Moral Distress and Burnout Syndrome: Are There Relationships between These Phenomena in Nursing Workers? Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2014, 22, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J. Employee Well-Being Initiatives: A Critical Analysis Of HRM Practices. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 6808–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zou, X.; Chen, H. Workload in ICU Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Nursing Activities Score. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 91, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, D.R.; Nap, R.; de Rijk, A.; Schaufeli, W.; Iapichino, G.; Members of the TISS Working Group. Nursing Activities Score. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Paskova, A. Moral distress among neonatal and pediatric intensive care nurses before and during COVID-19: A systematic review. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. Res. Sq. 2025; Preprint, Version 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamata, A.T.; Mohammadnezhad, M. A Systematic Review Study on the Factors Affecting Shortage of Nursing Workforce in the Hospitals. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Millere, I.; Nagle, E. Moral Distress, Professional Burnout, and Potential Staff Turnover in Intensive Care Nursing Practice in Latvia—Phase 1. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Paskova, A. Adaptation and Validation of the Moral Distress Scale-Healthcare Professionals in Latvia. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Millere, I.; Trups, I. Adaptation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Latvia: Psychometric Data and Factor Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, R.M.; Hinshaw, A.S.; Atwood, J.R. Anticipated turnover among nursing staff. Ariz. Nurse 1983, 36, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Raosoft, Inc. Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Elvira, S.; Romero-Béjar, J.L.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Monsalve-Reyes, C.; Cañadas-De La Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Burnout Levels in Intensive Care Unit Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, Z.; Simbota, M.; Mula, C. Nurses’ Perceptions on the Effects of High Nursing Workload on Patient Care in an Intensive Care Unit of a Referral Hospital in Malawi: A Qualitative Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, S.P.; Susanti, M. Effect of Work Overload on Job Satisfaction Through Burnout. J. Manaj. 2021, 25, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, E.; Campelo-Izquierdo, M.; Veiras, P.B.; Rodríguez, M.M.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Hortas, A.B.; Rodríguez-Calvo, M.S.; Rodríguez-Núñez, A. Moral Distress among Healthcare Professionals Working in Intensive Care Units in Spain. Med. Intensiv. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 46, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaurado-Serra, M.; Santos, E.C.; Grogues, M.P.; Constantinescu-Dobra, A.; Coţiu, M.-A.; Dobrowolska, B.; Friganović, A.; Gutysz-Wojnicka, A.; Hadjibalassi, M.; Ozga, D.; et al. Critical Care Nurses’ Intention to Leave and Related Factors: Survey Results from 5 European Countries. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 88, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villagran, C.A.; Dalmolin, G.D.L.; Barlem, E.L.D.; Greco, P.B.T.; Lanes, T.C.; Andolhe, R. Association between Moral Distress and Burnout Syndrome in University-Hospital Nurses. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2023, 31, e3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Shohaimi, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Kazeminia, M.; Bazrafshan, M.-R.; Mohammadi, M. The Severity of Moral Distress in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 2022, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Z.; Yang, P.; Singer, S.J.; Pfeffer, J.; Mathur, M.B.; Shanafelt, T. Nurse Burnout and Patient Safety, Satisfaction, and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2443059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyneel, A.; Smith, P.; Tack, J.; Pirson, M. Prevalence of Burnout Risk and Factors Associated with Burnout Risk among ICU Nurses during the COVID-19 Outbreak in French Speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021, 65, 103059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zeng, X.; Wu, X. Global Prevalence of Turnover Intention among Intensive Care Nurses: A Meta-analysis. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 28, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ji, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.E.; Squires, A. Moral Distress, Burnout, Turnover Intention, and Coping Strategies among Korean Nurses during the Late Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Method Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 5579322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolado, G.N.; Ataro, B.A.; Gadabo, C.K.; Ayana, A.S.; Kebamo, T.E.; Minuta, W.M. Stress Level and Associated Factors among Nurses Working in the Critical Care Unit and Emergency Rooms at Comprehensive Specialized Hospitals in Southern Ethiopia, 2023: Explanatory Sequential Mixed-Method Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyneel, A.; Tack, J.; Droguet, M.; Maes, J.; Wittebole, X.; Miranda, D.R.; Pierdomenico, L.D. Measuring the Nursing Workload in Intensive Care with the Nursing Activities Score (NAS): A Prospective Study in 16 Hospitals in Belgium. J. Crit. Care 2019, 54, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, L.A.; Gee, P.M.; Butler, R.J. Impact of Nurse Burnout on Organizational and Position Turnover. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusted Health. Front-Line Nurse Career Report: Flexibility Is Key—Findings and Recommendations from Trusted Health’s 2024 Report. TrustedHealth. 2024. Available online: https://works.trustedhealth.com/research/flexibility-is-key-findings-and-recommendations-from-trusted-healths-2024-front-line-nurse-career-report?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine. Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. In Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being; Factors Contributing to Clinician Burnout and Professional Well-Being; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552615/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- van der Riet, P.; Levett-Jones, T.; Aquino-Russell, C. The Effectiveness of Mindfulness Meditation for Nurses and Nursing Students: An Integrated Literature Review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 65, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Schoonover-Shoffner, K.; Kennedy, M.S. A Collaborative State of the Science Initiative: Transforming Moral Distress into Moral Resilience in Nursing. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117 (Suppl. S1), S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hospital | Shift | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Current Number of Nurses | Nurse Shortage (M) | Nurse Shortage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | D | 58.38 | 20.14 | 21.40 | 136.50 | 8 | 0.97 | 32.4 |

| N | 58.13 | 19.20 | 8 | 0.95 | 31.7 | |||

| B | D | 106.96 | 18.83 | 33.30 | 156.90 | 2 | 2.46 | 82.1 |

| N | 105.18 | 18.99 | 2 | 2.19 | 73.0 | |||

| C | D | 71.31 | 24.61 | 28.80 | 154.30 | 2 | 1.32 | 44.0 |

| N | 70.85 | 19.69 | 2 | 1.14 | 38.0 |

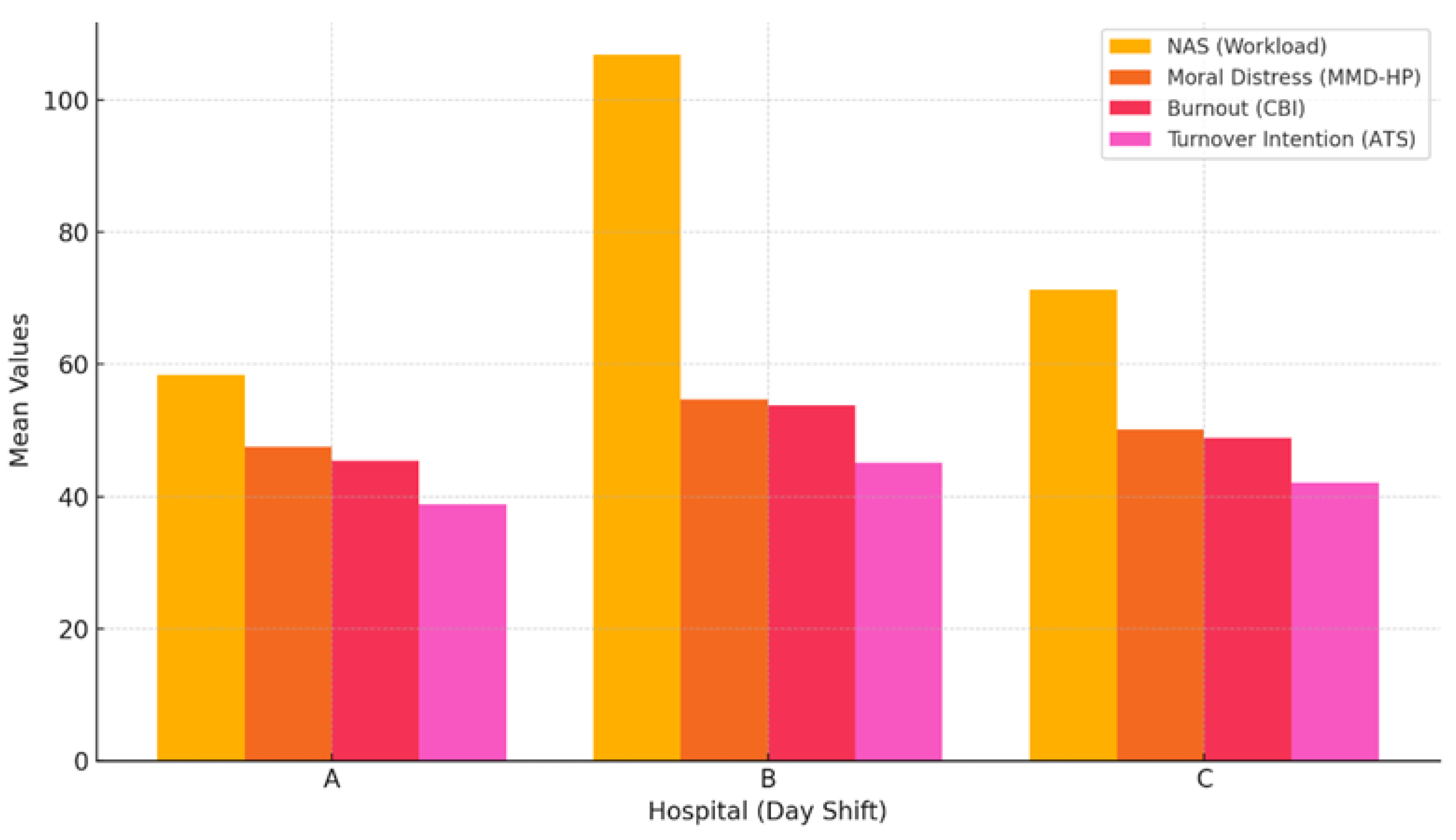

| Hospital | Shift | Mean | SD | Nurse Shortage (M) | MMD-HP (Mean) * | CBI (Mean) * | ATS (Mean) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | D | 58.38 | 20.14 | 32.4 | 47.6 | 45.4 | 38.9 |

| N | 58.13 | 19.20 | 31.7 | ||||

| B | D | 106.96 | 18.83 | 82.1 | 54.7 | 53.8 | 45.1 |

| N | 105.18 | 18.99 | 73.0 | ||||

| C | D | 71.31 | 24.61 | 44.0 | 50.1 | 48.9 | 42.1 |

| N | 70.85 | 19.69 | 38.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Millere, I. Exploring the Relation Between Nursing Workload and Moral Distress, Burnout, and Turnover in Latvian Intensive Care Units: An Ecological Analysis of Parallel Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091442

Cerela-Boltunova O, Millere I. Exploring the Relation Between Nursing Workload and Moral Distress, Burnout, and Turnover in Latvian Intensive Care Units: An Ecological Analysis of Parallel Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091442

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerela-Boltunova, Olga, and Inga Millere. 2025. "Exploring the Relation Between Nursing Workload and Moral Distress, Burnout, and Turnover in Latvian Intensive Care Units: An Ecological Analysis of Parallel Data" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091442

APA StyleCerela-Boltunova, O., & Millere, I. (2025). Exploring the Relation Between Nursing Workload and Moral Distress, Burnout, and Turnover in Latvian Intensive Care Units: An Ecological Analysis of Parallel Data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091442