Interventions to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Selection and Extraction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

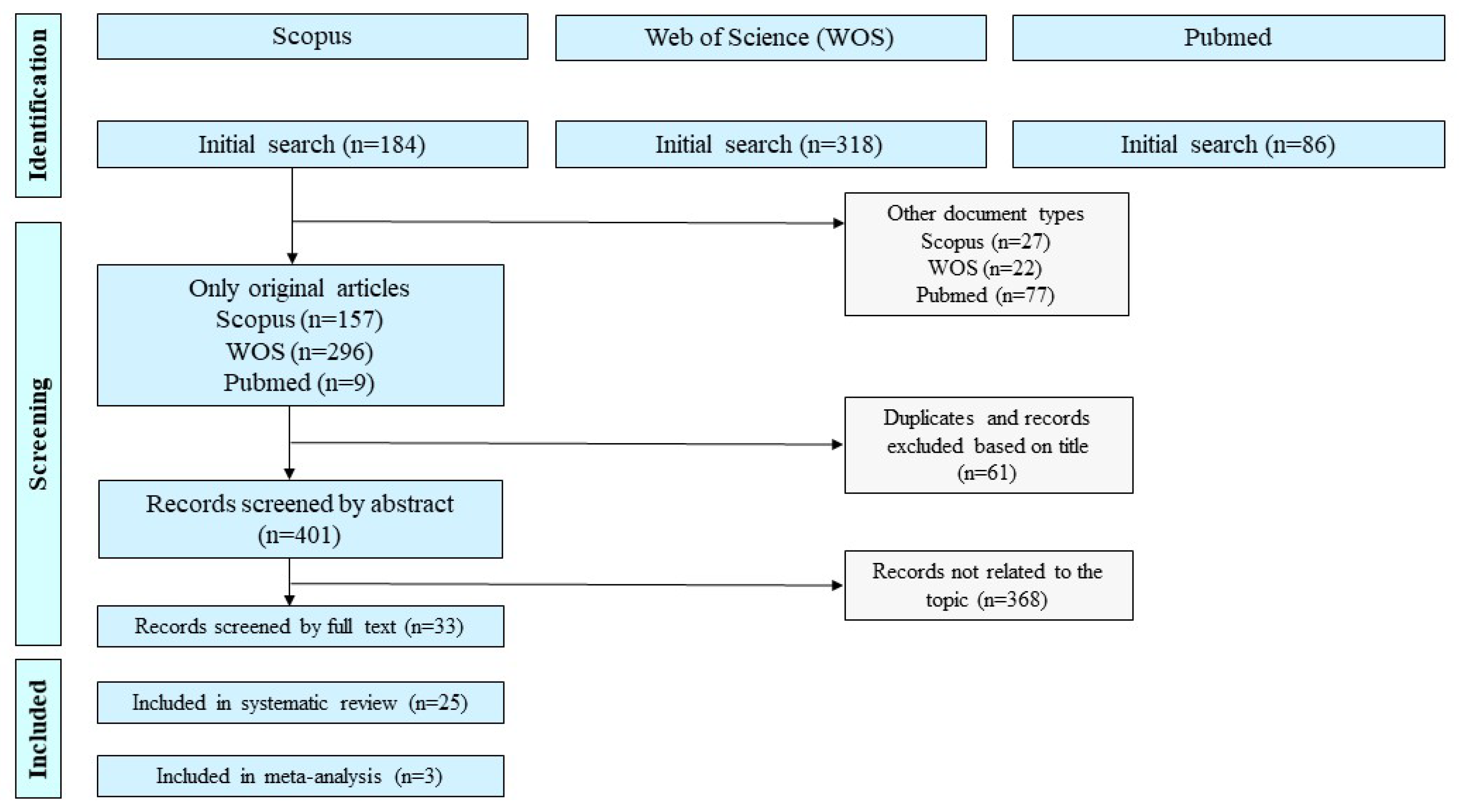

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Interventions

3.4. Outcomes of Interest

| First Author, Year | Country | Setting and District | Study Desing | Intervention Details | Target Group | Mental Health Focus of Intervention | Duration of Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahrens et al., 2020 [22] | Malawi | 5 districts in Southern Malawi: Mulanje, Thyolo, Machinga, Nsanje (Southern Region), Ntcheu (Central Region) | Pre–post study with qualitative components (focus groups) | A multifaceted program based on the WHO mhGAP intervention guide. It included a 2 day training for non-specialist PHC workers, followed by three months of monthly on-site supervision by mental health professionals. The program also incorporated community awareness events and formation of peer support groups. | Community health workers in rural PHC | Psychosis, moderate-severe depression, alcohol and substance use disorders | 2 day training and 3 months supervision | Knowledge, confidence, attitudes, detection and referral, perceived skills and collaboration |

| Beaulieu et al., 2017 [31] | Canada | PHC settings, Québec | Cluster RCT | A contact-based anti-stigma intervention delivered through three interactive workshops. The program included mental health education, direct contact with people with lived experience of mental illness, reflection activities, and interprofessional collaboration. | Physicians PHC | General mental illness | 3 workshop sessions delivered over a short time frame (exact duration not specified) | Stigmatizing attitudes, willingness to work with clients with mental illness, perceptions of individuals with mental disorders |

| Bellizzi et al., 2021 [15] | Egypt | Public health facilities in Port Said Governorate, primarily primary care settings | Pre–post study with follow-up assessment | A 3-day intensive mental health training workshop for nurses, including modules on communication, assessment, diagnosis, management of mental illness, stigma reduction, and policy issues. Training was based on mhGAP and adapted from similar programs in LMICs. Delivered via lectures, case studies, and problem-solving exercises. | Nurses | General mental illness, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, epilepsy, dementia | 3 consecutive training days with follow-up assessments at baseline, immediately post-training, and three months later | Significant short-term improvements in knowledge and attitudes; some decline at 3 months |

| Browne et al., 2018 [29] | Canada | Five PHC organizations in British Columbia | Mixed methods: pre–post surveys, qualitative interviews, focus groups | The EQUIP intervention was a multi-component organizational-level training initiative focused on equity-oriented care. It included modules on trauma- and violence-informed care, cultural safety, anti-racism, and mental health stigma reduction. Training was delivered via in-person team sessions, online modules, and action planning over 12 months. | Physicians, nurses, social workers | General mental illness (part of broader structural stigma addressed) | 12 months (with multiple components spread across the year) | Improved provider confidence and awareness; better communication and patient relationships |

| Doherty et al., 2018 [23] | South Africa | 22 PHC facilities across five districts of Northern Province, Sri Lanka: Jaffna, Mannar, Mullaitivu, Vavuniya, and Kilinochchi | Stepped-wedge cluster clinical trial | Training based on the WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide for primary care practitioners, public health professionals, and community representatives. It included modules on common mental health conditions, symptom recognition, management, psychoeducation, and referral pathways. | Common mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and psychosis | Common mental disorders (including depression, anxiety), chronic conditions | Initial training followed by two refresher sessions approximately 3 and 6 months later; duration ranged from 77 to 445 days due to disruptions | Changes in mental health stigma measured using the Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire (AMIQ) at six time points (pre-/post-training and refresher sessions) |

| Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2017 [37] | Spain | PHC centers in Catalonia and MH centers (12 total) | Cluster RCT Pre–post study (one group) | A structured training program (“Atención y Relación”) aimed at improving professionals’ attitudes toward mental illness, enhancing empathy, and reducing stigma when working with migrant populations. Included sessions on cultural competence, mental health education, emotional intelligence, and self-reflection, delivered via interactive workshops and case discussions. | General practitioners, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers. | General mental illness (focused on migrant and minority mental health) | Anti-stigma awareness program by Obertamen: 4 h training; 4 h self-diagnosis; follow-up; peer-led; social contact; reflection | Stigma levels measured via OMS-HC and BAMHS at 1 and 3 months; domains assessed included coercion and disclosure |

| Flanagan et al., 2016 [34] | USA | Primary care clinics in New Haven, Connecticut | RCT | Photovoice; Peer storytelling (Recovery Speaks) 1 h live presentation; discussion with peer leaders sharing lived experience; 10 week preparatory program for presenters | Physicians PHC | Mental illness, addiction | 1 session (approx. 1 h) | Outcomes assessed: stigma domains (stereotypes, fear, avoidance), empathy, and hope |

| Grandon et al., 2019 [35] | Chile | PHC Centers in the province of Concepción, including, Talcahuano, Chiguayante, Hualpen, and Tome. | Multicenter RCT | Six-week group-based program (Igual-Mente) combining education, contact with people with SMD, and skills training to reduce stigma among PHC staff. with persons with SMD, and role-play of real-life clinical situations to build inclusive communication and behavioral skills | Physicians, nurse, psychologists and social workers | Severe mental disorders | 6 weeks (1 session per week), 2 management sessions (timing not specified) | Significant reduction in stigmatizing attitudes, social distance, and community rejection; effects sustained at 4-month follow-up |

| Haddad et al., 2018 [36] | UK | 13 London Primary Care | Cluster RCT | Educational anti-stigma training including lectures, role-plays, discussions, videos, and contact-based components with service users. Aimed at improving nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward mental illness 1 full-day, 1 half-day follow-up training (4–6 weeks later); | School nurses | General mental illness | Approx. 1.5 days (spread over 4–6 weeks) | Knowledge and detection of depression, professional confidence, sensitivity, and optimism (assessed at 3 and 9 months) |

| Kaiser et al., 2022 [26] | Nepal | Primary care centers in Chitwan district | Cluster RCT; Qualitative (Explanatory mixed-methods design) | RESHAPE intervention: social contact with service users in recovery and aspirational figures (PCPs with mental health experience), incorporated into standard mhGAP training. Included recovery narratives, myth-busting, co-facilitation by people with lived experience. | Physicians PHC | Depression, psychosis, epilepsy, alcohol use disorder | 9 days (prescribers); 5 days (non-prescribers) | Knowledge and detection of depression, professional confidence, sensitivity, and optimism (assessed at 3 and 9 months) |

| Kohrt et al., 2022 [25] | Nepal | Primary care centers, Chitwan district | Pilot cluster RCT | RESHAPE: 9-day mhGAP training with participatory anti-stigma component using PhotoVoice narratives from PWLE, plus aspirational figures and social contact. Compared to TAU mhGAP only. Co-facilitated by trained people with lived experience and previous PCP trainees. | Physicians PHC | Depression, psychosis, alcohol use disorder | 9-day training; follow-up assessments at 4 and 16 months | Social distance, mental health knowledge and attitudes, diagnostic accuracy, and implicit stigma were assessed; feasibility and acceptability also evaluated |

| Li et al., 2015 [24] | China | Community mental health institutions in 8 districts of Guangzhou | Quasi-experimental (comparison of new training model vs. traditional) | New training curriculum (85 h: clinical; community psychiatry; public health; stigma); needs-based supervision, based on mhGAP and local guidelines | Mental health staff | General mental illness (not disorder-specific) | 14 days training; supervision every 3 months; outcomes assessed at 6 and 12 months | Mental health knowledge, stigma-related knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to engage with persons with mental illness were assessed at 6 and 12 months |

| Li et al., 2014 [16] | China | Community mental health institutions, 8 districts in Guangzhou | Pre–post study (uncontrolled) | One-day mental health training covering symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment (focus on schizophrenia and bipolar disorder); stigma education by experienced psychiatrists | Community mental health staff | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder | 1 day training course for community mental health staff; included knowledge enhancement, vignettes, and anti-stigma content | Stigma-related attitudes and willingness to engage were assessed; knowledge via vignettes showed no significant change |

| Marín et al., 2016 [21] | Chile | 2 CESFAMs in Metropolitan Region of Santiago | RCT (acceptability analysis of training phase only) | Training based on national depression guidelines: 60 h total (12 h per group), included lectures, clinical cases, role-play, OSCE, and simulations. Covered detection, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and stigma-related challenges. | Physician, psychologist, nurse, social workers | Depression | 60 h (over 10 sessions) | Perceptions of training acceptability and relevance assessed; stigma-related content present but not quantitatively evaluated |

| Mittal et al., 2019 [32] | USA | Two primary care centers, Central USA | Pilot RCT | Contact intervention: face-to-face narrative by peer with lived experience of SMI; group discussion; Education intervention: lecture-based session with PowerPoint; both had 1 month booster session | Physicians, nurses | Serious Mental Illness, schizophrenia focused vignette | 2 sessions over 1 month; follow-up at 3 months | Stigma-related outcomes assessed; mixed findings across measures; qualitative data indicated perceived awareness and intent to reduce stereotyping |

| Mroueh et al., 2021 [17] | Armenia | PHC settings in 5 regions (Armavir, Lori, Shirak, Syunik, Yerevan) | Pre–post quasi-experimental | One-day face-to-face workshop on schizophrenia and depression; included lectures, video case studies from WHO mhGAP, discussions; delivered by local psychiatrists | GPs, nurses | Depression and schizophrenia | 1 day | Significant improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and practices for both conditions among nurses and GPs (p < 0.001); data collected immediately post-training |

| Ng et al., 2017 [33] | Malaysia | Community PHC clinics, Beijing | Pilot RCT | 3 arms: (1) Lecture-only mhGAP-based training; (2) Contact-based training including service user testimony, education; (3) Waitlist control | Nurses | Mental illness (not specified) | Single training session (duration not specified) | OMS-HC scores improved significantly in contact group; no change in control; DISC-12 showed reduction in perceived discrimination among HCWs |

| Oladeji et al., 2023 [27] | Nigeria | 28 PHC clinics across 11 LGAs, Ibadan, Oyo State | Cluster RCT | Cascade training model: 3 day training using adapted mhGAP for perinatal depression; trained PHCW via blended learning (lectures, role-plays, group discussions); refresher training at 6 months | Doctors, nurses | Depression and psychosis | 3 day initial training, refresher at 6 months | Significant reduction in stigma and increase in mental health literacy (MHLS) at 3 months post-training |

| Payne et al., 2002 [18] | UK | 17 NHS Direct sites across England | Pre–post intervention study (survey before and after training) | SCAN training program developed by University of Manchester; delivered via 3-day core skills course and local cascade training | Nurses | Mental health (focus on depression, anxiety, psychosis) | 5 months follow-up | Assessed confidence, attitudes toward depression care, and knowledge; reported improvements, though some were non-significant |

| Rai et al., 2018 [39] | Nepal | PHC in Chitwan district | Qualitative study (key informant interviews) | RESHAPE program: mhGAP training with co-facilitation by service users with lived experience; training focused on stigma reduction and recovery | Primary Care Medical Professionals | Mental illness (depression, psychosis, alcohol use disorder) | 5 PhotoVoice sessions (first 3 days, rest 1 day), followed by co-facilitation of 6 mhGAP trainings | Improved communication skills, reduced family burden, increased self-confidence among service users, stigma reduction, peer support, caregiver engagement challenges identified |

| Rosendal et al., 2005 [30] | Denmark | PHC in Vejle County | Cluster RCT | Multifaceted training based on the Extended Reattribution and Management Model, including a residential course, local outreach visits, peer supervision, and booster sessions | GPs | Somatoform disorders | 25 h over 12 months | Decreased anxiety and anger; increased enjoyment and comfort in managing somatising patients |

| Roussy et al., 2020 [38] | Australia | PHC in Toronto, Ontario | Pre–post qualitative and quantitative study | 3 h consumer-led training delivered by individuals with co-occurring mental illness and substance use experience, involving personal stories, role-play, and education; preceded by a 3.5 h clinician-led training | Primary Care Medical Professionals | Psychosis/Severe mental illness | One session (1.5 h) | Improved knowledge and reduced stigmatizing attitudes among primary care providers (pre–post comparison) |

| Salazar et al., 2022 [19] | India | Rural primary health centres in Karnataka | Cluster RCT | Half-day training including didactic teaching and case-based discussions on CMDs for PHC doctors. Both intervention and control groups received training based on mhGAP and Indian national guidelines. | GPs | Common Mental Disorders (depression, anxiety, panic) | One session 3 h | Significant improvement in knowledge scores (MCQ test); negative attitudes towards depression persisted in 50% (assessed via R-DAQ) |

| Shirazi et al., 2011 [20] | Iran | 192 General Practitioners in primary care | RCT | Standard CME program with lectures. Tailored educational intervention based on stages of change (Prochaska model), using interactive methods such as role-play, standardized patients, buzz groups | GPs | Mental illness | Single 2 day workshop | Improved clinical performance in diagnosing (14%) and managing (20%) depression (measured via standardized patients) |

| Tilahun, et al., 2017 [28] | Ethiopia | SNNPR, rural PHC setting | Mixed methods (cross-sectional survey, qualitative interviews) | Training of 104 Health Extension Workers (HEWs) under the HEAT program with modules on child mental health and developmental disorders | Health Extension Workers | Child mental disorders (e.g., developmental disorders, autism) | Not explicitly stated; training completed 4 months before data collection | Improved knowledge, awareness, motivation; application of training in practice (e.g., case detection, community meetings); barriers and facilitators identified; stigma-related attitudes mentioned as barriers |

3.5. Risk of Bias Analysis

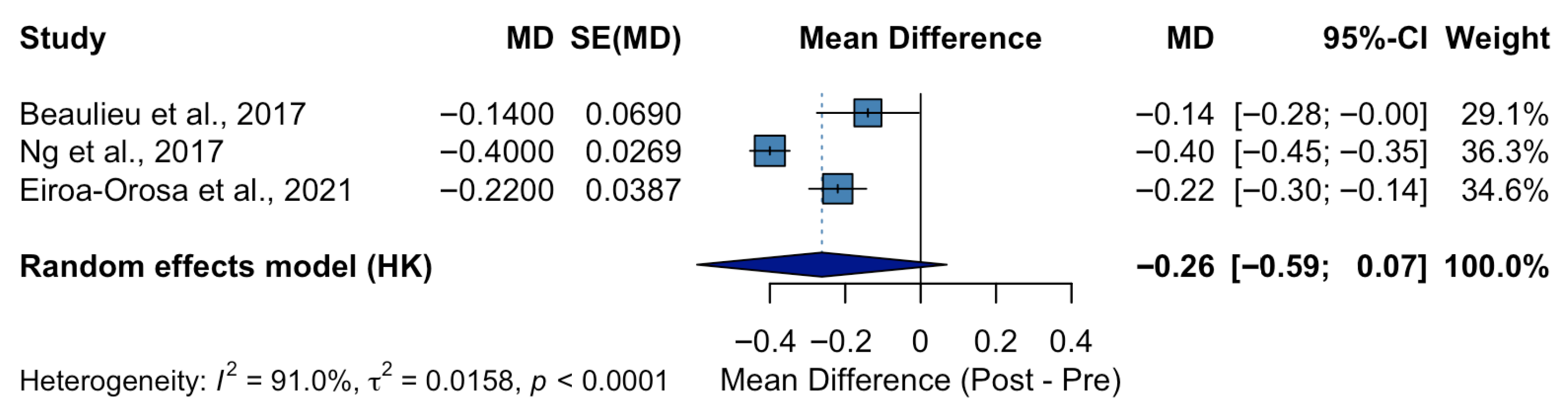

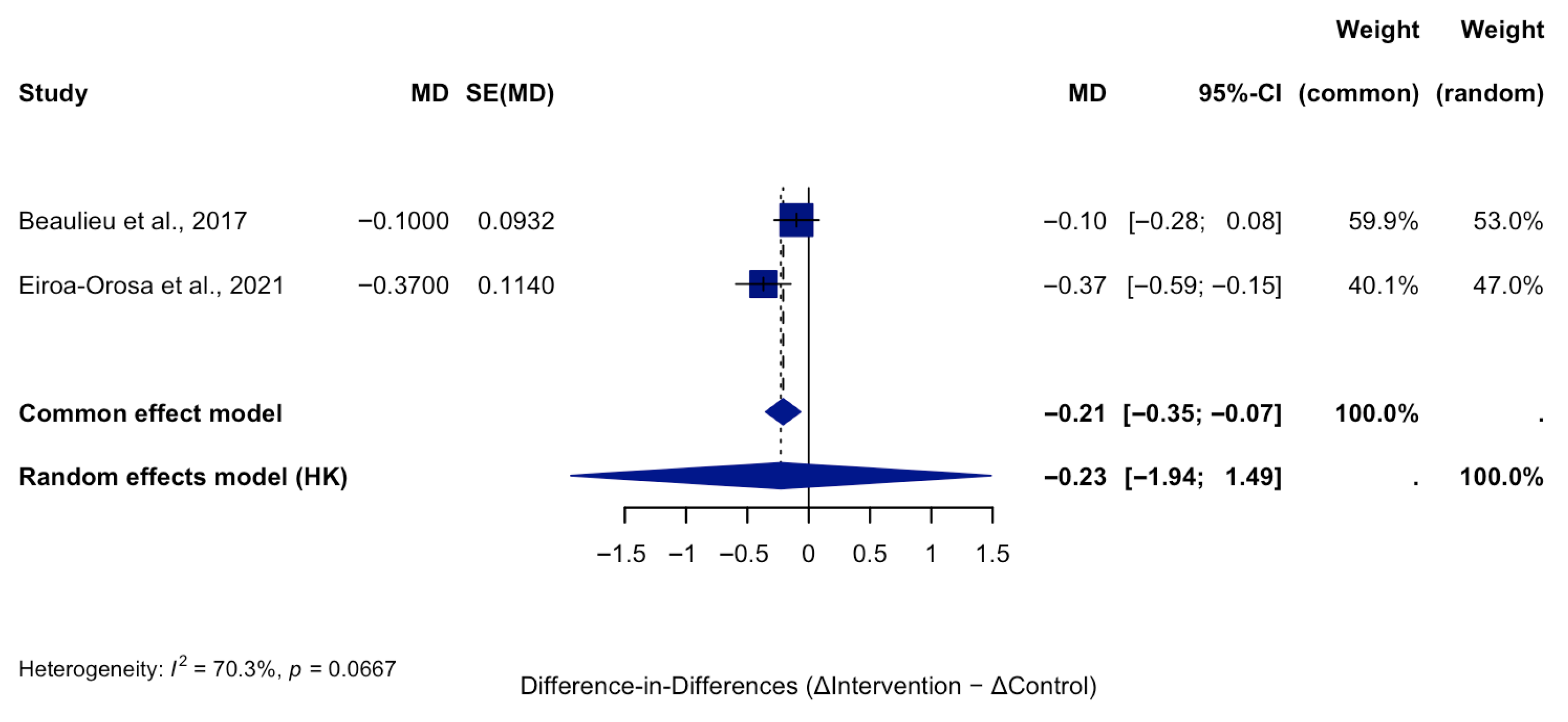

3.6. Effects of the Interventions

3.7. Summary of Main Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHC | Primary Healthcare |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews |

| WHO | World Health Organization’s |

| mhGAP | Mental Health Gap Action Programme |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| GPs | General Practitioners |

| MDs | Mean Differences |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ROBINS-I | Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist |

| PWLE | People With Lived Experience |

| OMS-HC | Opening Minds Scale for Health Care Providers |

| MICA | Mental Illness: Clinicians’ Attitudes Scale |

| EAPS-TM | Escala de Actitudes de los Profesionales de Salud hacia Personas con Trastornos Men-tales |

| PHPs | public health professionals |

| PCPs | primary care providers |

| AMIQ | Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire |

| DAQ | Depression Attitude Questionnaire |

| R-DAQ | Revised-Depression Attitudes Questionnaire |

| SCAN | Screen, Care, Advise, and decide on Next steps |

| SDS | Social Distance Scale |

| RESHAPE | reducing stigma among health providers |

| TAU | Training as Usual |

| VAS | Visual analogue scales |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual |

| EOHC | Equity-Oriented Health Care |

| SMD | Severe Mental Disorders |

| PCP | primary care providers |

| CESFAMs | Centro de Salud Familiar |

| OSCE | Objective Structured Clinical Examination |

| SMI | Serious Mental Illness |

| USA | United States of America |

| PHCW | healthcare workers |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| CMD | Common Mental Disorders |

| CME | Continuing Medical Education |

| SNNPR | Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region |

| HEWs | Health Extension Workers |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| LGAs | Local Government Areas |

| MHLS | Mental Health Literacy |

| MCQ | Multiple-Choice Questionnaires |

| ASHA | Accredited Social Health Activists |

| BAMHS | Beliefs and Attitudes towards Mental Health Service |

| EDSS | Electronic Decision Support |

| IVRS | Interactive voice response system |

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 ASEAN Mental Disorders Collaborators. The epidemiology and burden of ten mental disorders in countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), 1990–2021: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e480–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Barnett, P.; Greenburgh, A.; Pemovska, T.; Stefanidou, T.; Lyons, N.; Ikhtabi, S.; Talwar, S.; Francis, E.R.; Harris, S.M.; et al. Mental health in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeram, A.; Cross, W.; Townsin, L. Anti-stigma initiatives for mental health professionals—A systematic literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Noblett, J.; Parke, H.; Clement, S.; Caffrey, A.; Gale-Grant, O.; Schulze, B.; Druss, B.; Thornicroft, G. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistorte, A.O.R.; Ribeiro, W.S.; Jaen, D.; Jorge, M.R.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Mari, J.J. Stigmatizing attitudes of primary care professionals towards people with mental disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2018, 53, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, D.; Corrigan, P.; Sherman, M.D.; Chekuri, L.; Han, X.; Reaves, C.; Mukherjee, S.; Morris, S.; Sullivan, G. Healthcare providers’ attitudes toward persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2014, 37, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, O.V.; Ezeani, E.I.; Fatoye, E.O.; Benjamin, J.; Okobi, O.E.; Nwume, C.G.; Egberuare, E.N. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Stigmatization on Psychiatric Illness Outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e62642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, Y.Y.; Lin, H.S.; Lien, Y.J.; Tsai, C.H.; Wu, T.T.; Li, H.; Tu, Y.K. Challenging mental illness stigma in healthcare professionals and students: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol. Health 2021, 36, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.; Clement, S.; Marcus, E.; Stona, A.C.; Bezborodovs, N.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Palacios, J.; Docherty, M.; Barley, E.; Rose, D.; et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.M.; Chua, J.Y.X.; Chan, P.Y.; Shorey, S. Effectiveness of educational interventions in reducing the stigma of healthcare professionals and healthcare students towards mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 4074–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullock, S.P.; Scrivano, R.M. The effectiveness of mental illness stigma-reduction interventions: A systematic meta-review of meta-analyses. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 100, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: A systematic review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, S.; Khalil, A.; Sawahel, A.; Nivoli, A.; Lorettu, L.; Said, D.S.; Padrini, S. Impact of intensive training on mental health, the experience of Port Said, Egypt. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Thornicroft, G. Mental health training program for community mental health staff in Guangzhou, China: Effects on knowledge of mental illness and stigma. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroueh, L.; Ekmekdjian, D.; Aghekyan, E.; Sukiasyan, S.; Tadevosyan, M.; Simonyan, V.; Soghoyan, A.; Vincent, C.; Bruand, P.E.; Jamieson-Craig, T.; et al. Can a brief training intervention on schizophrenia and depression improve knowledge, attitudes and practices of primary healthcare workers? The experience in Armenia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2021, 66, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, F.; Harvey, K.; Jessopp, L.; Plummer, S.; Tylee, A.; Gournay, K. Knowledge, confidence and attitudes towards mental health of nurses working in NHS Direct and the effects of training. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 40, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.J.; Ekstrand, M.L.; Selvam, S.; Heylen, E.; Pradeep, J.R.; Srinivasan, K. The effect of mental health training on the knowledge of common mental disorders among medical officers in primary health centres in rural Karnataka. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, M.; Lonka, K.; Parikh, S.V.; Ristner, G.; Alaeddini, F.; Sadeghi, M.; Wahlstrom, R. A tailored educational intervention improves doctor’s performance in managing depression: A randomized controlled trial. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2013, 19, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, R.; Martinez, P.; Cornejo, J.P.; Diaz, B.; Peralta, J.; Tala, A.; Rojas, G. Chile: Acceptability of a Training Program for Depression Management in Primary Care. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, J.; Kokota, D.; Mafuta, C.; Konyani, M.; Chasweka, D.; Mwale, O.; Stewart, R.C.; Osborn, M.; Chikasema, B.; McHeka, M.; et al. Implementing an mhGAP-based training and supervision package to improve healthcare workers’ competencies and access to mental health care in Malawi. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.; Kianian, B.; Dass, G.; Edward, A.; Kone, A.; Manolova, G.; Sivayokan, S.; Solomon, M.; Surenthirakumaran, R.; Lopes-Cardozo, B. Changes in mental health stigma among healthcare professionals and community representatives in Northern Sri Lanka during an mhGAP intervention study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Thornicroft, G.; Yang, H.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y. Training community mental health staff in Guangzhou, China: Evaluation of the effect of a new training model. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, B.A.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Turner, E.L.; Rai, S.; Gurung, D.; Dhakal, M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Lamichhane, J.; Singla, D.R.; Lund, C.; et al. Collaboration with People with Lived Experience of Mental Illness to Reduce Stigma and Improve Primary Care Services: A Pilot Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2131475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, B.N.; Gurung, D.; Rai, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Dhakal, M.; Cafaro, C.L.; Sikkema, K.J.; Lund, C.; Patel, V.; Jordans, M.J.D.; et al. Mechanisms of action for stigma reduction among primary care providers following social contact with service users and aspirational figures in Nepal: An explanatory qualitative design. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladeji, B.D.; Ayinde, O.O.; Bello, T.; Kola, L.; Faregh, N.; Abdulmalik, J.; Zelkowitz, P.; Seedat, S.; Gureje, O. Cascade training for scaling up care for perinatal depression in primary care in Nigeria. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2023, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, D.; Hanlon, C.; Araya, M.; Davey, B.; Hoekstra, R.A.; Fekadu, A. Training needs and perspectives of community health workers in relation to integrating child mental health care into primary health care in a rural setting in sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Ford-Gilboe, M.; Nadine Wathen, C.; Smye, V.; Jackson, B.E.; Wallace, B.; Pauly, B.B.; Herbert, C.P.; Lavoie, J.G.; et al. Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational health equity intervention in primary care clinics. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendal, M.; Bro, F.; Sokolowski, I.; Fink, P.; Toft, T.; Olesen, F. A randomised controlled trial of brief training in assessment and treatment of somatisation: Effects on GPs’ attitudes. Fam. Pract. 2005, 22, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, T.; Patten, S.; Knaak, S.; Weinerman, R.; Campbell, H.; Lauria-Horner, B. Impact of Skill-Based Approaches in Reducing Stigma in Primary Care Physicians: Results from a Double-Blind, Parallel-Cluster, Randomized Controlled Trial. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Owen, R.R.; Ounpraseuth, S.; Chekuri, L.; Drummond, K.L.; Jennings, M.B.; Smith, J.L.; Sullivan, J.G.; Corrigan, P.W. Targeting stigma of mental illness among primary care providers: Findings from a pilot feasibility study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.P.; Rashid, A.; O’Brien, F. Determining the effectiveness of a video-based contact intervention in improving attitudes of Penang primary care nurses towards people with mental illness. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.H.; Buck, T.; Gamble, A.; Hunter, C.; Sewell, I.; Davidson, L. “Recovery Speaks”: A Photovoice Intervention to Reduce Stigma Among Primary Care Providers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandon, P.; Saldivia, S.; Cova, F.; Bustos, C.; Vaccari, P.; Ramirez-Vielma, R.; Vielma-Aguilera, A.; Zambrano, C.; Ortiz, C.; Knaak, S. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce stigma towards people with a severe mental disorder diagnosis in primary health care personnel: Programme Igual-Mente. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 305, 114259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Pinfold, V.; Ford, T.; Walsh, B.; Tylee, A. The effect of a training programme on school nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and depression recognition skills: The QUEST cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 83, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiroa-Orosa, F.J.; Lomascolo, M.; Tosas-Fernandez, A. Efficacy of an Intervention to Reduce Stigma Beliefs and Attitudes among Primary Care and Mental Health Professionals: Two Cluster Randomised-Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussy, V.; Thomacos, N.; Rudd, A.; Crockett, B. Enhancing health-care workers’ understanding and thinking about people living with co-occurring mental health and substance use issues through consumer-led training. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1567–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.; Gurung, D.; Kaiser, B.N.; Sikkema, K.J.; Dhakal, M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Tergesen, C.; Kohrt, B.A. A service user co-facilitated intervention to reduce mental illness stigma among primary healthcare workers: Utilizing perspectives of family members and caregivers. Fam. Syst. Health 2018, 36, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Sharma, N.; Mehra, A. Stigma for Mental Disorders among Nursing Staff in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2020, 11, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, D.; Kohrt, B.A.; Wahid, S.S.; Bhattarai, K.; Acharya, B.; Askri, F.; Ayele, B.; Bakolis, I.; Cherian, A.; Daniel, M.; et al. Adapting and piloting a social contact-based intervention to reduce mental health stigma among primary care providers: Protocol for a multi-site feasibility study. SSM-Ment. Health 2023, 4, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention Type | No. of Studies | Outcomes Improved | Sustainability/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational interventions (lectures, workshops, mhGAP-based training) | 12 | Improved knowledge, increased professional confidence, some positive change in attitudes | Gains often short-term; decline after 3–6 months without reinforcement |

| Contact-based interventions (direct or indirect interaction with persons with lived experience) | 7 | Strong improvement in empathy, reduction in social distance, more willingness to treat | Resource-intensive, require trained facilitators; scalability can be limited |

| Multicomponent/system-level interventions (combined education, contact, organizational change) | 6 | Broad improvements across knowledge, attitudes, empathy, and confidence; potential to shift | Complex implementation, require institutional support, may face organizational resistance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhamaliyeva, L.; Ablakimova, N.; Batyrova, A.; Veklenko, G.; Grjibovski, A.M.; Kudaibergenova, S.; Seksenbayev, N. Interventions to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091441

Zhamaliyeva L, Ablakimova N, Batyrova A, Veklenko G, Grjibovski AM, Kudaibergenova S, Seksenbayev N. Interventions to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091441

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhamaliyeva, Lazzat, Nurgul Ablakimova, Assemgul Batyrova, Galina Veklenko, Andrej M. Grjibovski, Sandugash Kudaibergenova, and Nursultan Seksenbayev. 2025. "Interventions to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091441

APA StyleZhamaliyeva, L., Ablakimova, N., Batyrova, A., Veklenko, G., Grjibovski, A. M., Kudaibergenova, S., & Seksenbayev, N. (2025). Interventions to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1441. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091441