Young Adults with Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison with Healthy Peers, Risk and Resilience Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk Factors for Mental Health Problems During COVID-19

1.2. Chronic Conditions in Young Adulthood

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- (1)

- Are YACCs more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than healthy peers—regarding symptoms of anxiety and depression, suicidal ideation, and loneliness, as well as positive mental health and life satisfaction? We expected that YACCs would experience a greater psychosocial burden compared with healthy peers.

- (2)

- Are there differences in the mental health trajectories between young adults with and without a chronic condition? We assumed that YACCs would exhibit non-resilient trajectories more frequently than healthy peers.

- (3)

- Which risk and protective factors predict resilient versus non-resilient trajectories in young adults with and without a chronic condition?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Differences Between YACCs and Healthy Peers at T1

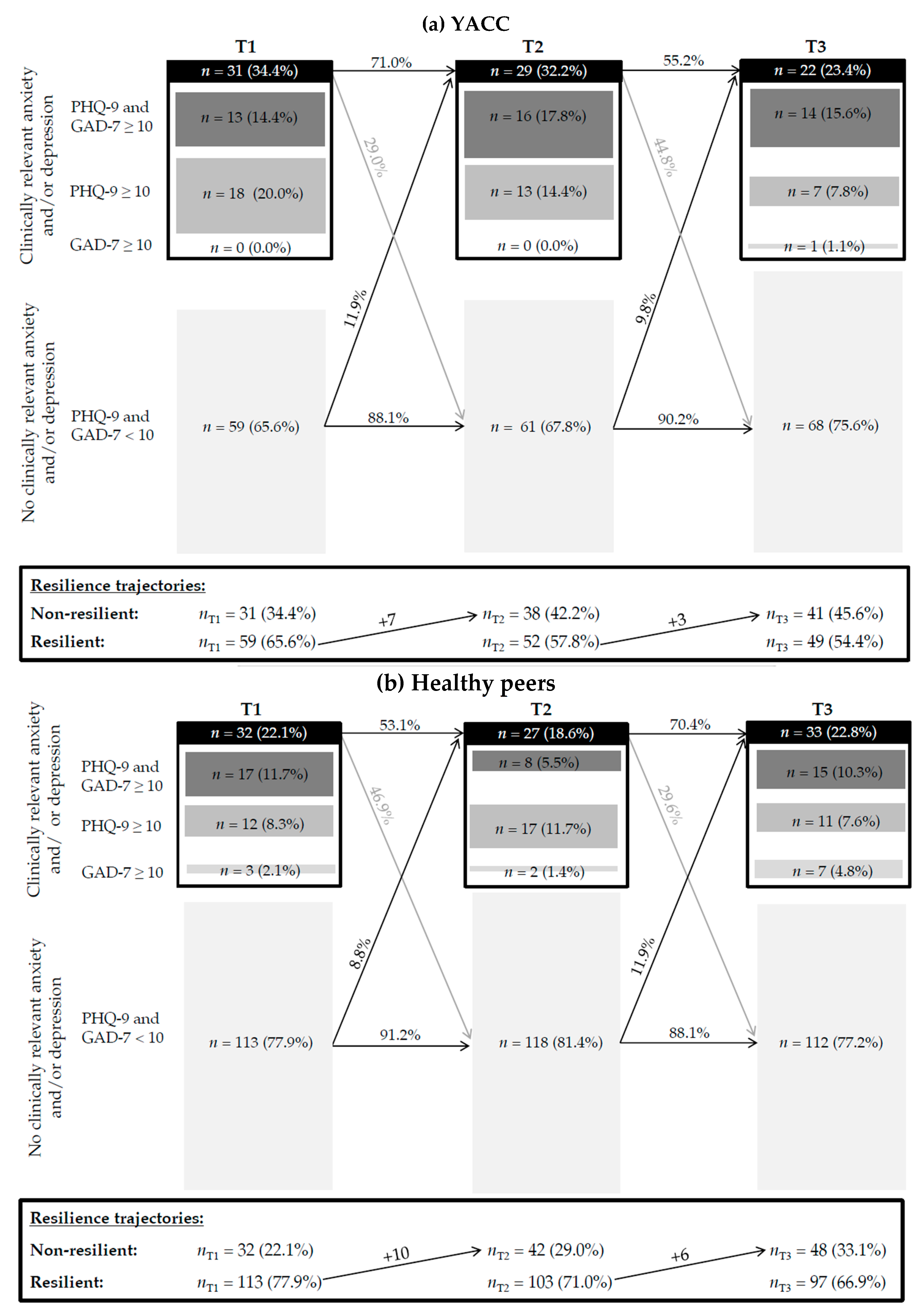

3.2. Differences in the Trajectories of Mental Health Problems Between YACCs and Healthy Peers (T1-T2-T3)

3.3. Prediction of Resilient Trajectories in Young Adults

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences Between YACCs and Healthy Peers at T1

4.2. Sex Differences

4.3. Differences in the Trajectories of Mental Health Problems Between YACCs and Healthy Peers (T1-T2-T3)

4.4. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener |

| FF | Future Family |

| FF-IV | Future Family IV study |

| FF-COVID-19 | Future Family COVID-19 study |

| FU18 | 18-year catamnesis/18-year follow-up |

| LSS | Life Satisfaction Scale |

| PHQ-9 | Depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| T1 | First assessment of the FF-COVID-19 study |

| T2 | Second assessment of the FF-COVID-19 study |

| T3 | Third assessment of the FF-COVID-19 study |

| YACCs | Young adults with chronic conditions |

References

- Bonati, M.; Campi, R.; Segre, G. Psychological impact of the quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic on the general European adult population: A systematic review of the evidence. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E. U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 954–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäuerle, A.; Teufel, M.; Musche, V.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Hetkamp, M.; Dörrie, N.; Schweda, A.; Skoda, E.M. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; McAllister, C.; Joiner, T.E. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in U.S. Census Bureau assessments of adults: Trends from 2019 to fall 2020 across demographic groups. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 83, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewale, L.Y. Psychological state, family functioning and coping strategies among undergraduate students in a Nigerian University during the COVID-19 lockdown. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E285–E295. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 2007, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, F.; Höfler, M.; Siegert, J.; Mack, S.; Gerschler, A.; Scholl, L.; Busch, M.A.; Hapke, U.; Maske, U.; Seiffert, I.; et al. Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: The Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1-MH). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 23, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, R.; Sujan, M.S.H.; Islam, M.S.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Hasan, M.M.; Koly, K.N.; Potenza, M.N. Depression and anxiety among individuals with medical conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a nationwide survey in Bangladesh. Acta Psychol. 2021, 220, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler-Kuo, M.; Dzemaili, S.; Foster, S.; Werlen, L.; Walitza, S. Stress and mental health among children/adolescents, their parents, and young adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A.; Jones, P.B.; Burn, A.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young adults’ mental health and beyond: A qualitative investigation nested within an ongoing general population cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 2203–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsa, M.; Sassine, S.; Yang, X.Y.; Gong, R.N.; Amir-Yazdani, P.; Sonia, T.A.; Gibson, M.; Drouin, O.; Chadi, N.; Jantchou, P. A qualitative study of adolescents and young adults’ experience and perceived needs during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. De Pédiatrie 2022, 29, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Gilbert, M.; Reiss, F.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Schlack, R.; et al. Child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of the three-wave longitudinal COPSY study. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlack, R.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Eicher, S.; Hölling, H.; Thom, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Beyer, A.K. Changes in mental health in the German child and adolescent population during the COVID-19 pandemic—Results of a rapid review. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8 (Suppl. 1), 2–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorini, C.; Cavallo, G.; Vettori, V.; Buscemi, P.; Ciardi, G.; Zanobini, P.; Okan, O.; Dadaczynski, K.; Lastrucci, V.; Bonaccorsi, G. Predictors of well-being, future anxiety, and multiple recurrent health complaints among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of socioeconomic determinants, sense of coherence, and digital health literacy. An Italian cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1210327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargav, M.; Swords, L. Risk factors for COVID-19-related stress among college-going students. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2024, 41, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R.; Nihei, O.K. Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Brazilian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Predictors and association with life satisfaction, psychological well-being and coping strategies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förtsch, K.; Viermann, R.; Reinauer, C.; Baumeister, H.; Warschburger, P.; Holl, R.W.; Domhardt, M.; Krassuski, L.M.; Platzbecker, A.L.; Kammering, H.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of adolescents with chronic medical conditions: Findings from a German pediatric outpatient clinic. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 847–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.T.; Andersen, T.O.; Clotworthy, A.; Jensen, A.K.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Rod, N.H.; Varga, T.V. Time trends in mental health indicators during the initial 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, M.; Horn, M.; Creupelandt, C.; Fovet, T.; Baubet, T.; Habran, E.; Martignène, N.; Vaiva, G.; D’Hondt, F. Mental Health Symptoms of University Students 15 Months After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in France. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2249342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Picaza Gorrotxategi, M.; Olaya, B.; Santabárbara, J. The emotional state of young people in northern Spain after one year and a half of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2023, 37, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helseth, S.; Abebe, D.S.; Andenæs, R. Mental health problems among individuals with persistent health challenges from adolescence to young adulthood: A population-based longitudinal study in Norway. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybdal, D.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Sildorf, S.M.; Boisen, K.A.; Svensson, J.; Skovgaard, A.M.; Teilmann, G.K. Increasing risk of psychiatric morbidity after childhood onset type 1 diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, S.; de Silva, M.; Fleming, T.; Clark, T.; Merry, S.; Ameratunga, S.; Milfont, T.; Farrant, B.; Fortune, S.A. The prevalence of chronic health conditions impacting on daily functioning and the association with emotional well-being among a national sample of high school students. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, C.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Beyer, A.K.; Baumert, J.; Thamm, R.; Maier, B.; Neuhauser, H.; Fuchs, J.; Kuhnert, R.; Hapke, U. Health situation of adults in Germany—Results for selected indicators from GEDA 2019/2020-EHIS. J. Health Monit. 2021, 6, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.W.; Cameron, F.J.; Joshi, K.; Eiswirth, M.; Garrett, C.; Garvey, K.; Agarwal, S.; Codner, E. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022, Diabetes in adolescence. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debowska, A.; Horeczy, B.; Boduszek, D.; Dolinski, D. A repeated cross-sectional survey assessing university students’ stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidality in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3744–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, F.; Schmits, E. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: The young adults most at risk. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, T.J.; Liang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, T.W.; Bonanno, G.A.; Hou, W.K. Trajectories of daily routine disruptions as functions of depressive and anxiety symptom trajectories and social determinants: A multi-wave population survey in Hong Kong. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 190, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, N.; Bertram, H.; Kuschel, A.; Hahlweg, K. Parent recruitment and retention in a universal prevention program for child behavior and emotional problems: Barriers to research and program participation. Prev. Sci. 2005, 6, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, N.; Krüger, S.; Guse, U. Der Einfluss von Anreizen auf die Rekrutierung von Eltern und auf die Effektivität eines präventiven Elterntrainings. Z. Für Klin. Psychol. Und Psychother. 2006, 35, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.; Buda, S.; Tolksdorf, K. Zweite Aktualisierung der Retrospektiven Phaseneinteilung der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland. Epidemiol. Bull. 2022, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Klein, A.M.; Brähler, E.; Glaesmer, H.; Luck, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Wirkner, K.; Hilbert, A. Psychometric evaluation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W. PHQ-D Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (2. Auflage). In Manual Komplettversion und Kurzversion; Pfizer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kliem, S.; Sachser, C.; Lohmann, A.; Baier, D.; Brähler, E.; Gündel, H.; Fegert, J.M. Psychometric evaluation and community norms of the PHQ-9, based on a representative German sample. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1483782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukat, J.; Margraf, J.; Lutz, R.; van der Veld, W.M.; Becker, E.S. Psychometric properties of the Positive Mental Health Scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychol. 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, G.; Herschbach, P. Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZM): A short questionnaire for assessing subjective quality of life. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2000, 16, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daig, I.; Spangenberg, L.; Henrich, G.; Herschbach, P.; Kienast, T.; Brähler, E. Alters- und geschlechtsspezifische Neunormierung der Fragen zur Lebenszufriedenheit (FLZM) für die Altersspanne von 14 bis 64 Jahre. Z. Für Klin. Psychol. Und Psychother. 2011, 40, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W.; Supke, M.; Hahlweg, K.; Job, A.K. Young adults with migration background: Mental health problems, risk behaviour, and educational and occupational development. Results of an 18-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2025, 30, 2480715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Wille, N.; Bettge, S.; Erhart, M. Psychische Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse aus der BELLA-Studie im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS) [Mental health of children and adolescents in Germany. Results from the BELLA study within the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007, 50, 871–878. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinelt, T.; Samdan, G.; Kiel, N.; Petermann, F. Frühkindliche Prädiktoren externalisierender Verhaltensauffälligkeiten: Evidenzen aus Längsschnittstudien [Predicting externalizing behavior problems in early childhood: Evidence from longitudinal studies]. Kindh. und Entwickl. 2019, 28, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulou, E.; Brandenburg, T.; Führer, D. Schilddrüsenerkrankungen bei Frauen und Männern—Status quo und neuer Forschungsbedarf [Diseases of the thyroid gland in men and women-Status quo and new research needs]. Inn. Med. 2023, 64, 758–765. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maske, U.E.; Busch, M.A.; Jacobi, F.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Hapke, U. Chronische somatische Erkrankungen und Beeinträchtigung der psychischen Gesundheit bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Querschnittsstudie Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell (GEDA) 2010 [Chronic somatic conditions and mental health problems in the general population in Germany. Results of the national telephone health interview survey “German health update (GEDA)” 2010]. Psychiatr. Prax. 2013, 40, 207–213. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taxiarchi, V.P.; Senior, M.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Carr, M.J.; Hope, H.; Hotopf, M.; Kontopantelis, E.; McManus, S.; Patalay, P.; Steeg, S.; et al. Changes to healthcare utilisation and symptoms for common mental health problems over the first 21 months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Parallel analyses of electronic health records and survey data in England. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2023, 32, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapke, U.; Cohrdes, C.; Nübel, J. Depressive symptoms in a European comparison—Results from the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) 2. J. Health Monit. 2019, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, W.; Hahlweg, K.; Job, A.K.; Supke, M. Prevalence, persistence, and course of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress of mothers and fathers. Results of an 18-year longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 344, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Du, J.; Chen, T.; Sheng, R.; Ma, J.; Ji, G.; Yu, F.; Ye, J.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; et al. Longitudinal changes in mental health among medical students in China during the COVID-19 epidemic: Depression, anxiety and stress at 1-year follow-up. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagi, L.; White, S.R.; Pinto Pereira, S.M.; Nugawela, M.D.; Heyman, I.; Sharma, K.; Stephenson, T.; Chalder, T.; Rojas, N.K.; Dalrymple, E.; et al. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of the CLoCk cohort study. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, e1004315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, S.R.; Fornal, C.A.; Wang, B.C.; Boyineni, J.; DeVera, R.E.; Unnam, P.; Song, Y.; Soares, M.B.; Malchenko, S.; Gyarmati, P.; et al. The Impact of Social Isolation and Environmental Deprivation on Blood Pressure and Depression-Like Behavior in Young Male and Female Mice. Chronic Stress 2023, 7, 24705470231207010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etheridge, B.; Spantig, L. The gender gap in mental well-being at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2022, 145, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, D.; Nilsson, K.W.; Stier, J.; Kerstis, B. The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrler, M.; Vogt, A.; Eichelberger, D.; Greutmann, M.; Hagmann, C.F.; Jenni, O.G.; Kretschmar, O.; Landolt, M.A.; Latal, B.; Wehrle, F.M. Psychological well-being in adults across the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Public Health 2025, 70, 1608347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, S.M.; Buck, C.; Matos Fialho, P.M.; Pischke, C.R.; Stock, C.; Heumann, E.; Zeeb, H.; Negash, S.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Niephaus, Y.; et al. Factors associated with substance use and physical activity among German university students 20 months into the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Prev. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrath, C.; Tittel, S.R.; Buchal, G.; Brämswig, S.; Preiss, E.; Göldel, J.M.; Wiegand, S.; Minden, K.; Warschburger, P.; Stahl-Pehe, A.; et al. Psychosocial burden during the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents with type 1 diabetes in Germany and its association with metabolic control. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.C.; Tou, N.X.; Low, J.A. Internet Use and Effects on Mental Well-being During the Lockdown Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Younger Versus Older Adults: Observational Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e46824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenberg, C.; Grossfurthner, M.; Andrich, J.; Hübner, L.; Kietaibl, S.; Holocher-Benetka, S. The Relationship Between the Implementation of Statutory Preventative Measures, Perceived Susceptibility of COVID-19, and Personality Traits in the Initial Stage of Corona-Related Lockdown: A German and Austrian Population Online Survey. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 596281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, R.L.; Johnson, S.T.; Simone, M.; Loth, K.A.; Berge, J.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress, mood, and substance use among young adults in the greater Minneapolis-St. Paul area: Findings from project EAT. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 276, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, I.; Cohen-Louck, K.; Bonny-Noach, H. Gender, employment, and continuous pandemic as predictors of alcohol and drug consumption during the COVID-19. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 228, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Alioto, A.; Amato, A.; Rossi, C.; Messina, G.; Bruno, M.R.; Stallone, R.; Proia, P. Fighting the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Mindfulness, exercise, and nutrition practices to reduce eating disorders and promote sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. Coping behaviors and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Situational and habitual effects on mental distress with hybrid model analysis. Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Ma, J.; Song, J.; Yan, C.; Yan, M. Associations between exercise and university students’ depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: The mediating role of relative deprivation and subjective exercise experience. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, M.; Naderi, M.; Zahednezhad, H.; Ghadirian, F. Effectiveness of an online mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological distress among patients with COVID-19 after hospital discharge. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Biological sex | |

| 138 (50.7) |

| 134 (49.3) |

| Migration background | |

| 219 (80.5) |

| 53 (19.5) |

| Current living situation | |

| 190 (69.9) |

| 82 (30.1) |

| Current intimate relationship | |

| 145 (53.3) |

| 127 (46.7) |

| Already have children of their own | |

| 262 (96.3) |

| 10 (3.7) |

| Highest school degree | |

| 25 (9.2) |

| 41 (15.1) |

| 206 (75.7) |

| Already completed professional training | |

| 186 (68.4) |

| 86 (31.6) |

| Current main activity | |

| 147 (54.0) |

| 37 (13.6) |

| 55 (20.2) |

| 19 (7.0) |

| 14 (5.1) |

| Chronic Conditions | t | df | p (1-Tailed) | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | 6.34 (4.60) | 7.62 (5.04) | −2.14 | 269 | 0.017 * | −0.27 |

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7) | 4.87 (3.91) | 5.91 (4.15) | −2.07 | 269 | 0.020 * | −0.26 |

| Positive mental health (PMH) | 28.10 (5.61) | 26.78 (6.10) | 1.82 | 269 | 0.035 * | 0.23 |

| Life satisfaction (LSS) | 53.38 (31.07) | 44.52 (33.57) | 2.43 | 266 | 0.008 ** | 0.31 |

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | df | p (1-tailed) | Φ | |

| Clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) | 0.05 | 1 | 0.414 | 0.01 | ||

| 147 (86.0) | 85 (85.0) | ||||

| 24 (14.0) | 15 (15.0) | ||||

| Clinically relevant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | 5.27 | 1 | 0.011 * | 0.14 | ||

| 136 (79.5) | 67 (67.0) | ||||

| 35 (20.5) | 33 (33.0) | ||||

| Suicidal ideation (last 2 weeks) | 1.51 | 1 | 0.110 | 0.08 | ||

| 151 (88.3) | 83 (83.0) | ||||

| 20 (11.7) | 17 (17.0) | ||||

| Loneliness 1 (last 2 weeks) | 0.17 | 1 | 0.342 | 0.03 | ||

| 74 (47.7) | 41 (45.1) | ||||

| 81 (52.3) | 50 (54.9) | ||||

| Chronic Conditions | t | df | p (1-Tailed) | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||||||

| 6.05 (4.56) | 6.94 (5.29) | −0.95 | 132 | 0.173 | −0.20 |

| 6.75 (4.65) | 7.97 (4.90) | −1.50 | 135 | 0.068 # | −0.26 |

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7) | ||||||

| 4.60 (3.97) | 4.82 (3.70) | −0.29 | 132 | 0.387 | −0.12 |

| 5.24 (3.93) | 6.47 (4.28) | −1.78 | 135 | 0.039 * | −0.30 |

| Positive mental health (PMH) | ||||||

| 28.47 (5.24) | 28.18 (5.83) | 0.27 | 132 | 0.393 | 0.08 |

| 27.59 (6.11) | 26.06 (6.16) | 1.15 | 135 | 0.073 # | 0.25 |

| Life satisfaction (LSS) | ||||||

| 52.34 (32.15) | 40.94 (38.22) | 1.69 | 130 | 0.046 * | 0.33 |

| 57.20 (29.51) | 46.38 (31.01) | 2.08 | 134 | 0.020 * | 0.36 |

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | df | p (1-tailed) | Φ | |

| Men | ||||||

| Clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) | 0.13 | 1 | 0.360 | 0.03 | ||

| 89 (89.0) | 31 (91.2) | ||||

| 11 (11.0) | 3 (8.8) | ||||

| Clinically relevant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | 0.86 | 1 | 0.178 | 0.08 | ||

| 81 (81.0) | 25 (73.5) | ||||

| 19 (19.0) | 9 (26.5) | ||||

| Suicidal ideation (last 2 weeks) | 0.63 | 1 | 0.401 | 0.02 | ||

| 87 (87.0) | 29 (85.3) | ||||

| 13 (13.0) | 5 (14.7) | ||||

| Loneliness 1 (last 2 weeks) | 0.40 | 1 | 0.264 | 0.06 | ||

| 44 (50.0) | 13 (43.3) | ||||

| 44 (50.0) | 17 (56.7) | ||||

| Women | ||||||

| Clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) | 0.00 | 1 | 0.493 | 0.00 | ||

| 58 (81.7) | 54 (81.8) | ||||

| 13 (18.3) | 12 (18.2) | ||||

| Clinically relevant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | 3.16 | 1 | 0.038 * | 0.15 | ||

| 55 (77.5) | 42 (63.6) | ||||

| 16 (22.5) | 24 (36.4) | ||||

| Suicidal ideation (last 2 weeks) | 1.98 | 1 | 0.079 # | 0.12 | ||

| 64 (90.1) | 54 (81.8) | ||||

| 7 (9.9) | 12 (18.2) | ||||

| Loneliness 1 (last 2 weeks) | 0.16 | 1 | 0.449 | 0.01 | ||

| 30 (44.8) | 28 (45.9) | ||||

| 37 (55.2) | 33 (54.1) | ||||

| Trajectory of Psychological Symptoms | Chronic Conditions | χ2 | df | p (1-Tailed) | Φ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Resilient 1 | 97 (66.9) | 49 (54.4) | 3.66 | 1 | 0.028 | 0.13 |

| Non-resilient 2 | 48 (33.1) | 41 (45.6) | ||||

| Total | 145 | 90 | ||||

| Independent Variable | B | Wald | df | p | OR [95–KI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic condition | 0.525 | 3.63 | 1 | 0.057 # | 1.69 [0.99−2.90] |

| Cox & Snell R2 = 0.015, Nagelkerkes R2 = 0.021 | |||||

| Sex | 0.618 | 5.087 | 1 | 0.024 * | 1.86 [1.08−3.18] |

| Cox & Snell R2 = 0.022, Nagelkerkes R2 = 0.030 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Job, A.-K.; Saßmann, H. Young Adults with Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison with Healthy Peers, Risk and Resilience Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091431

Job A-K, Saßmann H. Young Adults with Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison with Healthy Peers, Risk and Resilience Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091431

Chicago/Turabian StyleJob, Ann-Katrin, and Heike Saßmann. 2025. "Young Adults with Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison with Healthy Peers, Risk and Resilience Factors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091431

APA StyleJob, A.-K., & Saßmann, H. (2025). Young Adults with Chronic Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison with Healthy Peers, Risk and Resilience Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091431