Sex and Gender Influences on the Impacts of Disasters: A Rapid Review of Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

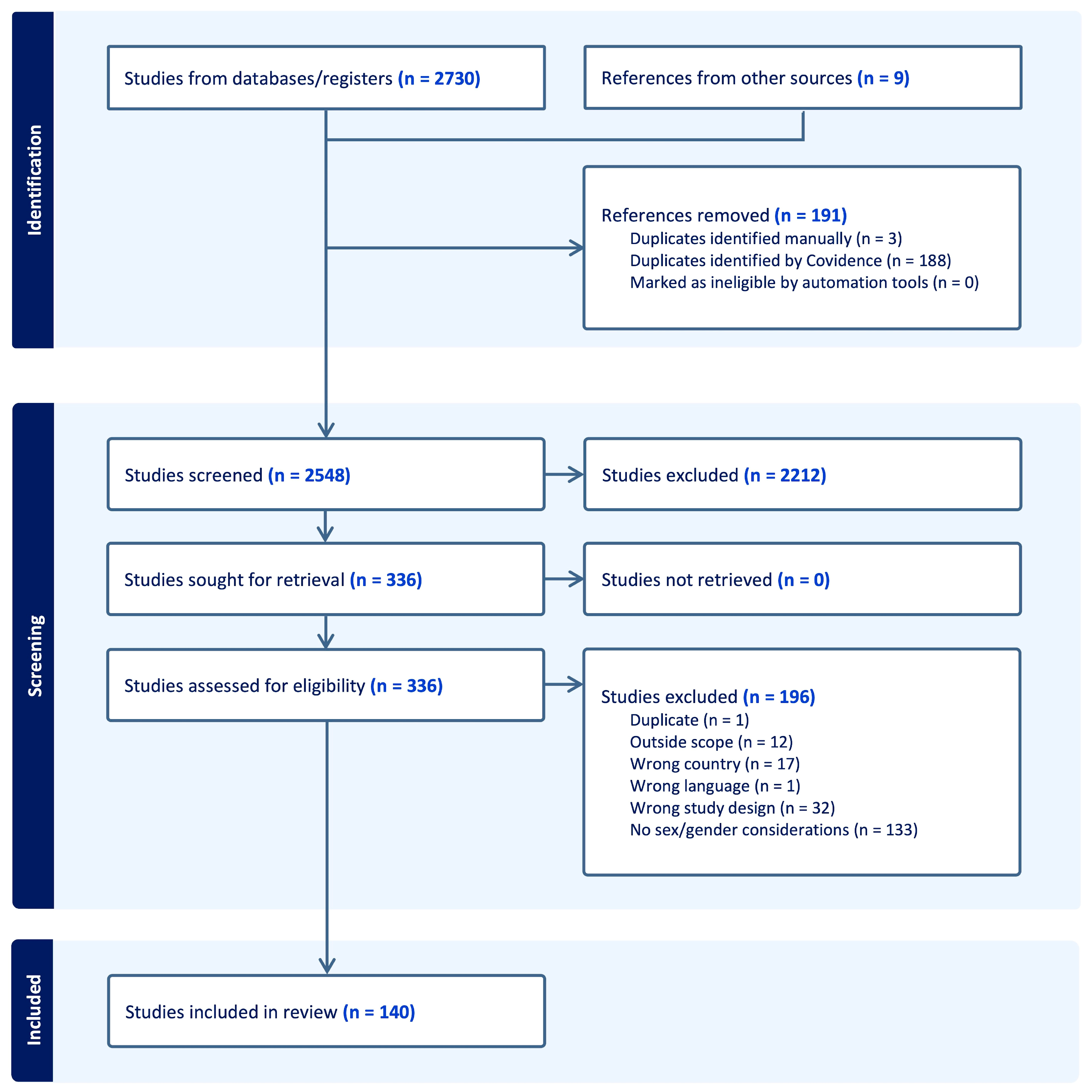

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Literature Screening, Study Selection, and Categorization

3. Results

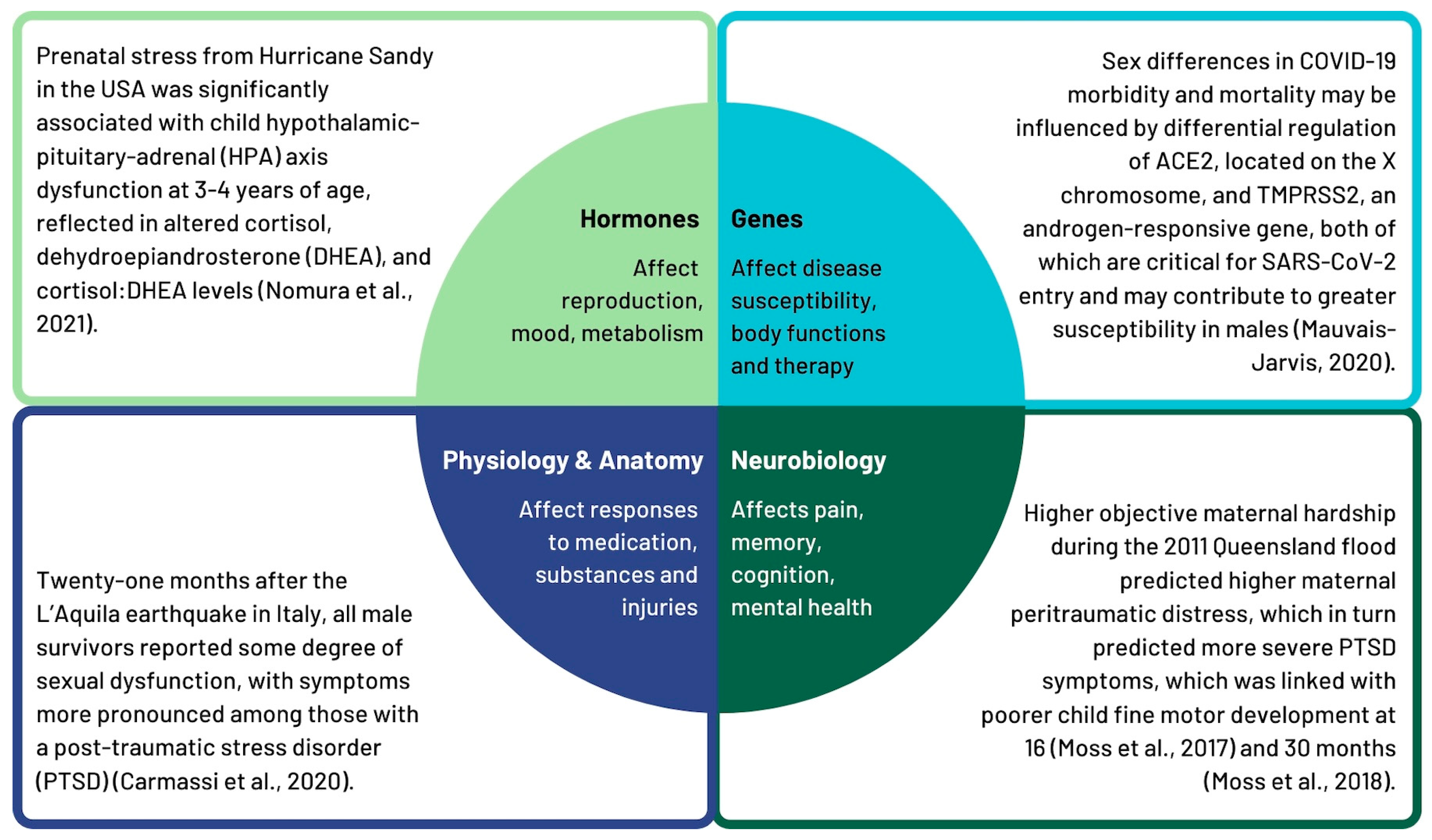

3.1. Sex-Related Factors Influencing the Impacts of Emergencies and Disasters

3.1.1. Hormones

3.1.2. Genes

3.1.3. Neurobiology

3.1.4. Physiology and Anatomy

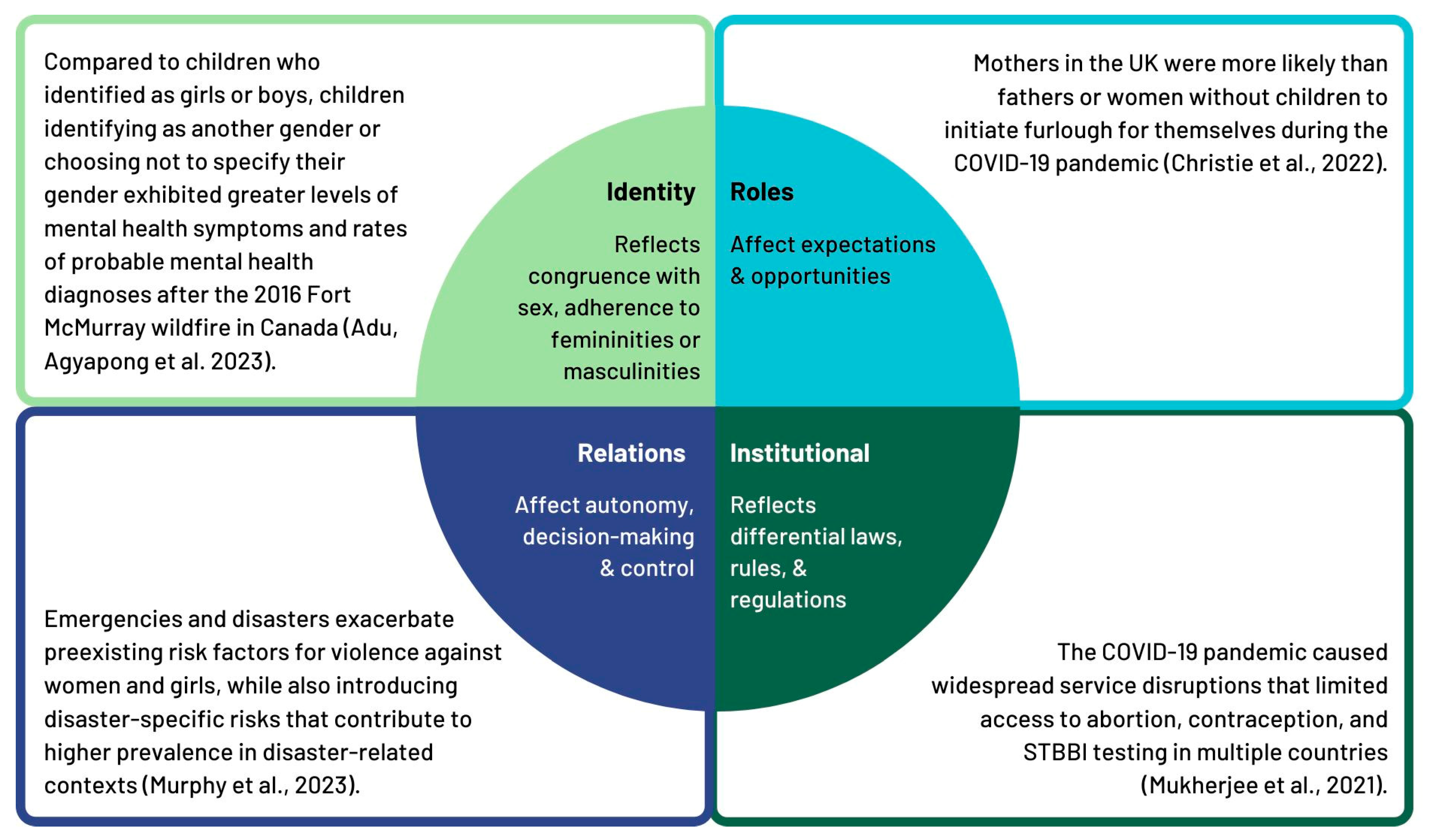

3.2. Gender-Related Factors Influencing the Impacts of Emergencies and Disasters

3.2.1. Identity

3.2.2. Roles

3.2.3. Relations

3.2.4. Institutional

3.2.5. Sex and Gender Differences in the Impacts of Emergencies and Disasters

3.3. Sex/Gender and Intersecting Considerations

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parkinson, D. The Way He Tells It: Relationships After Black Saturday—Volume 2: Women and Disasters Literature Review; Women’s Health Goulburn North East: Wangaratta, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cocina-Diaz, V.; Dema-Moreno, S.; Llorente-Marron, M. Gender Inequalities in Contexts of Disasters of Natural Origin: A Systematic Review. Int. Multidiscip. J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinzie, A.E.; Clay-Warner, J. The Gendered Effect of Disasters on Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2021, 39, 227–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neria, Y.; Nandi, A.; Galea, S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enarson, E.; Fothergill, A.; Peek, L. Gender and Disaster: Foundations and New Directions for Research and Practice. In Handbook of Disaster Resarch, 2nd ed.; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., DeLamater, J., Eds.; Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zortea, T.C.; Kolves, K.; Russell, K.; Mathieu, S.; Platt, S. Natural disasters and suicidal behaviour: An updated systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 375, 256–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, M.; Silverman, A.L.; Thompson, A.; Pumariega, A. Youth Suicidality in the Context of Disasters. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, B.; Kurtz, L.C. Vulnerability. In Handbook of Disaster Resarch, 2nd ed.; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., DeLamater, J., Eds.; Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendis, K.; Thayaparan, M.; Kaluarachchi, Y.; Pathirage, C. Challenges Faced by Marginalized Communities in a Post-Disaster Context: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stough, L.M.; Kelman, I. People with Disabilities and Disasters. In Handbook of Disaster Resarch, 2nd ed.; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., DeLamater, J., Eds.; Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.R.; Morley, S.K.; West, T.A.; Pentecost, P.; Upton, L.A.; Banks, L. Improving Long-Term Care Facility Disaster Preparedness and Response: A Literature Review. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 2017, 11, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D.; Duncan, A.; Joyce, K.; Jeffrey, J.; Archer, F.; Weiss, C.; Gorman-Murray, A.; McKinnon, S.; Dominey-Howes, D. Gender and Emergency Management (GEM) Guidelines: A Literature Review; Gender & Disaster Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, A.M.; Stockl, H.; Ranganathan, M. Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: A global mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, A.; Blanchard, K.; Weber, R.; Murray, V. Disasters and food security: The impact on health. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, I.; Mavridou, T.; Seymour, V.; Nanos, N. Post-disaster housing and social considerations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 124, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, W.G.; Dash, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zandt, S.V. Post-Disaster Sheltering, Temporary Housing and Permanent Housing Recovery. In Handbook of Disaster Resarch, 2nd ed.; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J.E., DeLamater, J., Eds.; Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Walton, L.; Koenig, K. Disaster Resilience: Addressing Gender Disparities. World Med. Health Policy 2016, 8, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, S.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Li, X.; Lebel, S.p.; Dagenais, C.; King, S. Effect of Natural Disaster-Related Prenatal Maternal Stress on Child Development and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2023: Creating the Conditions for Resilient Communities: A Public Health Approach to Emergencies; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves, L.; Poole, N.; Huber, E.; Muñoz Nieves, C. A gendered emergency framework: Integrating sex, gender and equity into emergency management [Forthcoming]. Can. J. Emerg. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Antony, J.; Zarin, W.; Strifler, L.; Ghassemi, M.; Ivory, J.; Perrier, L.; Hutton, B.; Moher, D.; Straus, S.E. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, L.; Ritz, S.A. Sex, Gender and Health: Mapping the Landscape of Research and Policy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Rompala, G.; Pritchett, L.; Aushev, V.; Chen, J.; Hurd, Y.L. Natural disaster stress during pregnancy is linked to reprogramming of the placenta transcriptome in relation to anxiety and stress hormones in young offspring. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6520–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Pedrinelli, V.; Barberi, F.M.; Rossi, R.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Dell’Osso, L. Is sexual dysfunction in young adult survivors to the L’Aquila earthquake related to post-traumatic stress disorder? A gender perspective. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Aging, Male Sex, Obesity, and Metabolic Inflammation Create the Perfect Storm for COVID-19. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, K.M.; Simcock, G.; Cobham, V.; Kildea, S.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; King, S. A potential psychological mechanism linking disaster-related prenatal maternal stress with child cognitive and motor development at 16 months: The QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, K.M.; Simcock, G.; Cobham, V.E.; Kildea, S.; Laplante, D.P.; King, S. Continuous, emerging, and dissipating associations between prenatal maternal stress and child cognitive and motor development: The QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 119, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, E.Y.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Jones, S.L.; Brunet, A.; King, S. Disaster-related prenatal maternal stress predicts HPA reactivity and psychopathology in adolescent offspring: Project Ice Storm. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 117, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, D.P.; Simcock, G.; Cao-Lei, L.; Mouallem, M.; Elgbeili, G.; Brunet, A.; Cobham, V.; Kildea, S.; King, S. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene and child’s sex moderate the relationship between disaster-related prenatal maternal stress and autism spectrum disorder traits: The QF2011 Queensland flood study. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.-L.; Yogendran, S.; Dufoix, R.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; King, S. Prenatal maternal stress from a natural disaster and hippocampal volumes: Gene-by-environment interactions in young adolescents from project ice storm. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 706660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao-Lei, L.; Dancause, K.N.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; Szyf, M.; King, S. Pregnant women’s cognitive appraisal of a natural disaster affects their children’s BMI and central adiposity via DNA methylation: Project Ice Storm. Early Hum. Dev. 2016, 103, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kello, E.; Vieira, A.R.; Rivas-Tumanyan, S.; Campos-Rivera, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, K.G.; Buxo, C.J.; Morou-Bermudez, E. Pre- and peri-natal hurricane exposure alters DNA methylation patterns in children. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.C.; Jurado, A.; Abad-Molina, C.; Orduna, A.; Yarce, O.; Navas, A.M.; Cunill, V.; Escobar, D.; Boix, F.; Burillo-Sanz, S.; et al. The age again in the eye of the COVID-19 storm: Evidence-based decision making. Immun. Ageing 2021, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Harville, E.W.; Mattison, D.R.; Elkind-Hirsch, K.; Pridjian, G.; Buekens, P. Hurricane Katrina experience and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among pregnant women. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2010, 5, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.L.; Dufoix, R.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Patel, R.; Chakravarty, M.M.; King, S.; Pruessner, J.C. Larger amygdala volume mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and higher levels of externalizing behaviors: Sex specific effects in project ice storm. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qureshi, M.N.I.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Jones, S.L.; Long, X.; Paquin, V.; Bezgin, G.; Lussier, F.; King, S.; et al. Atypical brain structure and function in young adults exposed to disaster-related prenatal maternal stress: Project Ice Storm. J. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 101, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Naveed Iqbal Qureshi, M.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Paquin, V.; Lee Jones, S.; King, S.; Rosa-Neto, P. Decreased amygdala-sensorimotor connectivity mediates the association between prenatal stress and broad autism phenotype in young adults: Project Ice Storm. Stress 2024, 27, 2293698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambeskovic, M.; Laplante, D.P.; Kenney, T.; Elgbeili, G.; Beaumier, P.; Azat, N.; Simcock, G.; Kildea, S.; King, S.; Metz, G.A.S. Elemental analysis of hair provides biomarkers of maternal hardship linked to adverse behavioural outcomes in 4-year-old children: The QF2011 Queensland Flood Study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2022, 73, 127036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, G.; Cobham, V.E.; Laplante, D.P.; Elgbeili, G.; Gruber, R.; Kildea, S.; King, S. A cross-lagged panel analysis of children’s sleep, attention, and mood in a prenatally stressed cohort: The QF2011 Queensland flood study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 255, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simcock, G.; Kildea, S.; Elgbeili, G.; Laplante, D.P.; Stapleton, H.; Cobham, V.; King, S. Age-related changes in the effects of stress in pregnancy on infant motor development by maternal report: The Queensland flood study. Dev. Psychobiol. 2016, 58, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Barberi, F.M.; Pedrinelli, V.; Cordone, A.; Cappelli, A.; Cremone, I.M.; Rossi, R.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Dell’Osso, L. Do somatic symptoms relate to PTSD and gender after earthquake exposure? A cross-sectional study on young adult survivors in Italy. CNS Spectr. Int. J. Neuropsychiatr. Med. 2021, 26, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Foghi, C.; Diadema, E.; Mucci, F.; Massimetti, G.; Rossi, A.; Dell’Osso, L. Disrupted rhythmicity and vegetative functions relate to PTSD and gender in earthquake survivors. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 492006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Janmohamed, K.; Nyhan, K.; Forastiere, L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Kågesten, A.; Uhlich, M.; Sarpong Frimpong, A.; Van de Velde, S.; Francis, J.M.; et al. Sexual health (excluding reproductive health, intimate partner violence and gender-based violence) and COVID-19: A scoping review. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2021, 97, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.A.; Bahn, A.; Deutchman, D.; Bower, J.L.; Weems, C.F.; Alfano, C.A. Sleep disturbances and delayed sleep timing are associated with greater post-traumatic stress symptoms in youth following hurricane harvey. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 54, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.; Bansal, A.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; Cherbuin, N.; Peek, M.J.; Davis, D.L. Birth Outcomes, Health, and Health Care Needs of Childbearing Women following Wildfire Disasters: An Integrative, State-of-the-Science Review. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 086001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tingting, Y.; Huang, W.; Yu, P.; Chen, G.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke on Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, F.; Das, A.; Chatterjee, S. Drawing the Linkage Between Women’s Reproductive Health, Climate Change, Natural Disaster, and Climate-driven Migration: Focusing on Low- and Middle-income Countries—A Systematic Overview. Indian J. Community Med. 2024, 49, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Gao, Y.; Xu, R.; Yang, Z.; Yu, P.; Ye, T.; Ritchie, E.A.; Li, S.; Guo, Y. Health Effects of Cyclones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 86001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Fukuda, K.; Mason, S.; Shimizu, T.; Andersen, C.Y. Effects of earthquakes and other natural catastrophic events on the sex ratio of newborn infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 140, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.K.; Agyapong, B.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Children’s Psychological Reactions to Wildfires: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Ellsberg, M.; Balogun, A.; García-Moreno, C. Risk and protective factors for violence against women and girls living in conflict and natural disaster-affected settings: A systematic review. Trauma. Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 3328–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, H.; Hiscox, L.V.; Halligan, S.L.; Creswell, C. Examining harmful impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures on parents and carers in the United Kingdom: A rapid review. JCPP Adv. 2022, 2, e12095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, T.I.; Khan, A.G.; Dasgupta, A.; Samari, G. Reproductive justice in the time of COVID-19: A systematic review of the indirect impacts of COVID-19 on sexual and reproductive health. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binet, ë.; Ouellet, M.-C.; Lebel, J.; Békés, V.; Morin, C.M.; Bergeron, N.; Campbell, T.; Ghosh, S.; Bouchard, S.; Guay, S.; et al. A portrait of mental health services utilization and perceived barriers to care in men and women evacuated during the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfires. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.; Hendrikx, J.; Johnson, J. The impact of avalanche education on risk perception, confidence, and decision-making among backcountry skiers. Leis. Sci. 2022, 47, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, P.; Petrucci, O.; Rossi, M.; Bianchi, C.; Pasqua, A.A.; Guzzetti, F. Gender, age and circumstances analysis of flood and landslide fatalities in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seldomridge, A.C.; Wang, D.C.; Dryjanska, L.; Schwartz, J.P. Adherence to gender roles on ptsd symptoms of hurricane harvey survivors. J. Loss Trauma 2024, 29, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocina Diaz, V.; Dema Moreno, S.; Llorente Marron, M. Reproduction of and alterations in gender roles in the rescue of material goods after the 2011 earthquake in Lorca (Spain). J. Gend. Stud. 2024, 33, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, S.B.; Thomas, P.A.; Ruck, B.; Marshall, E.G.; Davidow, A.L. Poisonings After a Hurricane: Lessons From the New Jersey Poison Information and Education System (NJPIES) During and Following Hurricane Sandy. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, E.C.; Shabahang, M.M. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Need for Disaster Planning in Surgical Education. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021, 232, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.J.; Blacker, A.; Kalia, I. ‘Watching the tsunami come’: A case study of female healthcare provider experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.A.; Folkerth, L.A. Women’s Mental Health and Intimate Partner Violence Following Natural Disaster: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2016, 31, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, E.; Kaniasty, K.; Sukkyung, Y.; Canino, G.; You, S. Parent-Child Relationship Quality and Gender as Moderators of the Influence of Hurricane Exposure on Physical Health Among Children and Youth. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, M.R.; Vernberg, E.M.; Lochman, J.E.; McDonald, K.L.; Jarrett, M.A.; Hendrickson, M.L.; Powell, N. Co-reminiscing with a caregiver about a devastating tornado: Association with adolescent anxiety symptoms. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, A.; Marchetti, F.; Zambri, F.; Pro, E.; Brillo, E.; Colaceci, S. Breastfeeding and humanitarian emergencies: The experiences of pregnant and lactating women during the earthquake in Abruzzo, Italy. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, N.K.; Wilson, D.; Tappis, H.; Bertrand, D.; Veenema, T.; Glass, N. Experiences of pregnant women exposed to Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the US Virgin Islands: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, M.; Velez Vega, C.M.; Murphy, C.B.; Rosario, Z.; Torres, H.; Russell, E.; Brown, P.; Huerta-Montanez, G.; Watkins, D.; Meeker, J.D.; et al. Impact of hurricanes Irma and Maria on Puerto Rico maternal and child health research programs. Matern. Child Health J. 2020, 24, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, R.M.; House, L.D.; Salvesen von Essen, B.; Kortsmit, K.; Hernandez Virella, W.; Vargas Bernal, M.I.; Galang, R.R.; D’Angelo, D.V.; Shapiro-Mendoza, C.K.; Ellington, S.R. Pregnant Women’s Experiences During and After Hurricanes Irma and Maria, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Puerto Rico, 2018. Public Health Rep. 2023, 138, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnayake Mudiyanselage, S.; Davis, D.; Kurz, E.; Atchan, M. Infant and young child feeding during natural disasters: A systematic integrative literature review. Women Birth 2022, 35, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hine, R.H.; Mitchell, E.; Whitehead-Annett, L.; Duncan, Z.; McArdle, A. Natural disasters and perinatal mental health: What are the impacts on perinatal women and the service system? J. Public Health 2024, 32, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, L.; Srivastava, S.; Ajin, A.; Rana, S.S.; Mathkor, D.M.; Haque, S.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Ahmad, F. Etiology and incidence of postpartum depression among birthing women in the scenario of pandemics, geopolitical conflicts and natural disasters: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 44, 2278016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Greca, A.M.; Tarlow, N.; Brodar, K.E.; Danzi, B.A.; Comer, J.S. The stress before the storm: Psychological correlates of hurricane-related evacuation stressors on mothers and children. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Mughal, M.K.; Giallo, R.; Kingston, D. Predictors of child resilience in a community-based cohort facing flood as natural disaster. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.M.; Lee, S.J.; Ward, K.P.; Pu, D.F. The perfect storm: Hidden risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Maltreatment 2021, 26, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayat, A.A.; Sahebdel, S.; Jafari, S.; Kabirian, A.; Rahnejat, A.M.; Farahani, R.H.; Mosaed, R.; Nour, M.G. Evaluating the prevalence of PTSD among children and adolescents after earthquakes and floods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Pacitti, F.; Carmassi, C.; Rossi, A.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Hyland, P. The Italian version of the International Trauma Questionnaire: Symptom and network structure of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of late adolescents exposed to a natural disaster. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 859877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.; Yilmaz, D.Y.; Ertekin, K. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth, and rumination in adolescents after earthquake: A systematic review. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 35, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orengo-Aguayo, R.; Stewart, R.W.; de Arellano, M.A.; Suarez-Kindy, J.L.; Young, J. Disaster Exposure and Mental Health Among Puerto Rican Youths After Hurricane Maria. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, A.; Sautner, B.; Omege, J.; Denga, E.; Nwaka, B.; Akinjise, I.; Corbett, S.E.; Moosavi, S.; Greenshaw, A.; Chue, P.; et al. Long-Term Mental Health Effects of a Devastating Wildfire Are Amplified by Sociodemographic and Clinical Antecedents in College Students. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, B.; Kulig, J.; Botey, A.P. Counselling children after wildfires: A school-based approach. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2017, 51, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Forresi, B.; Soncini, F.; Bottosso, E.; Di Pietro, E.; Scarpini, G.; Scaini, S.; Aggazzotti, G.; Caffo, E.; Righi, E. Post-traumatic stress disorder, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents 2 years after the 2012 earthquake in Italy: An epidemiological cross-sectional study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, I.H.; Cobham, V.E. Psychological interventions for children experiencing PTSD after exposure to a natural disaster: A scoping review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 249–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A.; Sachser, C.; Fegert, J.r.M. Scoping review on trauma and recovery in youth after natural disasters: What Europe can learn from natural disasters around the world. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, B.S.; La Greca, A.M.; Brincks, A.; Colgan, C.A.; D’Amico, M.P.; Lowe, S.; Kelley, M.L. Trajectories of Posttraumatic Stress in Youths After Natural Disasters. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2036682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, G.Y.; Zacher, M.; Merdjanoff, A.; Do, M.P.; Pham, N.K. The effects of cumulative natural disaster exposure on adolescent psychological distress. J. Appl. Res. Child. 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, E.; Ugarte, L.; Azasu, E.; White, A.J. A Tsunami of Concern: The Lasting Impacts of COVID Isolation and School Closures on Youth Mental Health. Mo. Med. 2023, 120, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Hrabok, M.; Juhas, M.; Omeje, J.; Denga, E.; Nwaka, B.; Akinjise, I.; Corbett, S.E.; Moosavi, S.; Brown, M.; et al. Prevalence Rates and Predictors of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms in Residents of Fort McMurray Six Months After a Wildfire. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchini, V.; Giusti, L.; Salza, A.; Cofini, V.; Cifone, M.G.; Casacchia, M.; Fabiani, L.; Roncone, R. Moderate depression promotes posttraumatic growth (Ptg): A young population survey 2 years after the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2017, 13, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostrom, T.G.A.; Cullen, P.; Peters, S.A.E. The indirect health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: A review. J. Child Health Care 2023, 27, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, A.; Hajcak, G.; Danzig, A.P.; Black, S.R.; Bromet, E.J.; Carlson, G.A.; Kotov, R.; Klein, D.N. Neural reactivity to emotional stimuli prospectively predicts the impact of a natural disaster on psychiatric symptoms in children. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nuttman-Shwartz, O. Behavioral Responses in Youth Exposed to Natural Disasters and Political Conflict. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccanello, D.; Burro, R.; Hall, R. Children’s emotional experience two years after an earthquake: An exploration of knowledge of earthquakes and associated emotions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, E.D.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Kia-Keating, M.; Liu, S.R.; Binmoeller, C.; Terzieva, A. The influence of flood exposure and subsequent stressors on youth social-emotional health. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayaz, I. Posttraumatic growth and trauma from natural disaster in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review about related factors. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2023, 32, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleville, G.; Ouellet, M.-C.; Lebel, J.; Ghosh, S.; Morin, C.M.; Bouchard, S.; Guay, S.; Bergeron, N.; Campbell, T.; MacMaster, F.P. Psychological Symptoms Among Evacuees From the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: A Population-Based Survey One Year Later. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 655357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielson, C.K.; Sumner, J.A.; Adams, Z.W.; McCauley, J.L.; Carpenter, M.; Amstadter, A.B.; Ruggiero, K.J. Adolescent substance use following a deadly US tornado outbreak: A population-based study of 2,000 families. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 46, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A.L.; Flores, C.M.N.; Feinberg, D.K.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Young, J.; Stewart, R.W.; Orengo-Aguayo, R.E. A network analysis of Hurricane Maria-related traumatic stress and substance use among Puerto Rican youth. J. Trauma. Stress 2024, 37, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia Coco, L.; Wilson, A.; Mickley, L.J.; Keita, E.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Yun, W.; Peng, R.D.; Xu, Y.; Dominici, F.; Bell, M.L. Who Among the Elderly Is Most Vulnerable to Exposure to and Health Risks of Fine Particulate Matter From Wildfire Smoke? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, W.R.; Lin, Z.; Lipton, E.A.; Birkhead, G.; Primeau, M.; Dong, G.H.; Lin, S. After the Storm: Short-term and Long-term Health Effects Following Superstorm Sandy among the Elderly. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgs, L.W. Elevated chronic bronchitis diagnosis risk among women in a local emergency department patient population associated with the 2012 heatwave and drought in Douglas county, NE USA. Heart Lung 2020, 49, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruchno, R.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Heid, A.R.; Cartwright, F.P. Effects of peri-traumatic stress experienced during hurricane sandy on functional limitation trajectories for older men and women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 281, 114097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, A.M.; Gwon, Y.; Gribble, M.O.; Berman, J.D.; Bilotta, R.; Hobbins, M.; Bell, J.E. Drought and all-cause mortality in Nebraska from 1980 to 2014: Time-series analyses by age, sex, race, urbanicity and drought severity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 840, 156660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arday, J.; Jones, C. Same storm, different boats: The impact of COVID-19 on Black students and academic staff in UK and US higher education. High. Educ. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manove, E.E.; Lowe, S.R.; Bonumwezi, J.; Preston, J.; Waters, M.C.; Rhodes, J.E. Posttraumatic growth in low-income Black mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D.; Duncan, A.; Leonard, W.; Archer, F. Lesbian and Bisexual Women’s Experience of Emergency Management. Gend. Issues 2022, 39, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubach, R.D.; Owens, C. Findings on the monkeypox exposure mitigation strategies employed by men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 3653–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, J.E.; Riddle, L.; Perez-Aguilar, G. ‘Prison life is very hard and it’s made harder if you’re isolated’: COVID-19 risk mitigation strategies and the mental health of incarcerated women in California. Int. J. Prison. Health 2023, 19, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manove, E.E.; Poon, C.Y.S.; Rhodes, J.E.; Lowe, S.R. Changes in psychosocial resources as predictors of posttraumatic growth: A longitudinal study of low-income, female Hurricane Katrina survivors. Traumatology 2021, 27, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, H.; Errett, N.A.; Eisenman, D.P. Working with Disaster-Affected Communities to Envision Healthier Futures: A Trauma-Informed Approach to Post-Disaster Recovery Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slick, J.; Parker, C.; Valoroso, A. Research Snapshot: Federal, Provincial and Territorial Government Actions to Address Gender-Based Violence During the Pandemic; Royal Roads University: Victoria, BC, Canada; Canadian Women’s Foundation: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, D. Investigating the Increase in Domestic Violence Post Disaster: An Australian Case Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 2333–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations Population Fund; United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Gender Action Plan to Support Implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gender and Disaster Australia. National Gender and Emergency Management (GEM) Guidelines. Available online: https://genderanddisaster.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1_GEM-Guidelines-December-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Gender and Disaster Australia. Gender & Disaster Australia Organisational CV. Available online: https://genderanddisaster.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/GADAus-Organisational-CV_January-2025.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Gender and Disaster Australia. Gender and Emergency Management Action Checklist. Available online: https://genderanddisaster.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1B_GEM-Guidelines-CHECKLIST-December-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Nieves, C.; Greaves, L.; Huber, E.; Brabete, A.C.; Wolfson, L.; Poole, N. Sex and Gender Influences on the Impacts of Disasters: A Rapid Review of Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091417

Muñoz-Nieves C, Greaves L, Huber E, Brabete AC, Wolfson L, Poole N. Sex and Gender Influences on the Impacts of Disasters: A Rapid Review of Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091417

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Nieves, Carol, Lorraine Greaves, Ella Huber, Andreea C. Brabete, Lindsay Wolfson, and Nancy Poole. 2025. "Sex and Gender Influences on the Impacts of Disasters: A Rapid Review of Evidence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091417

APA StyleMuñoz-Nieves, C., Greaves, L., Huber, E., Brabete, A. C., Wolfson, L., & Poole, N. (2025). Sex and Gender Influences on the Impacts of Disasters: A Rapid Review of Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091417