Quality over Quantity: The Association Between Daily Social Interactions and Loneliness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Dimensions of Social Interaction

1.2. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Quantitative Measures of Social Interactions

2.4. Qualitative Measures of Social Interactions

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

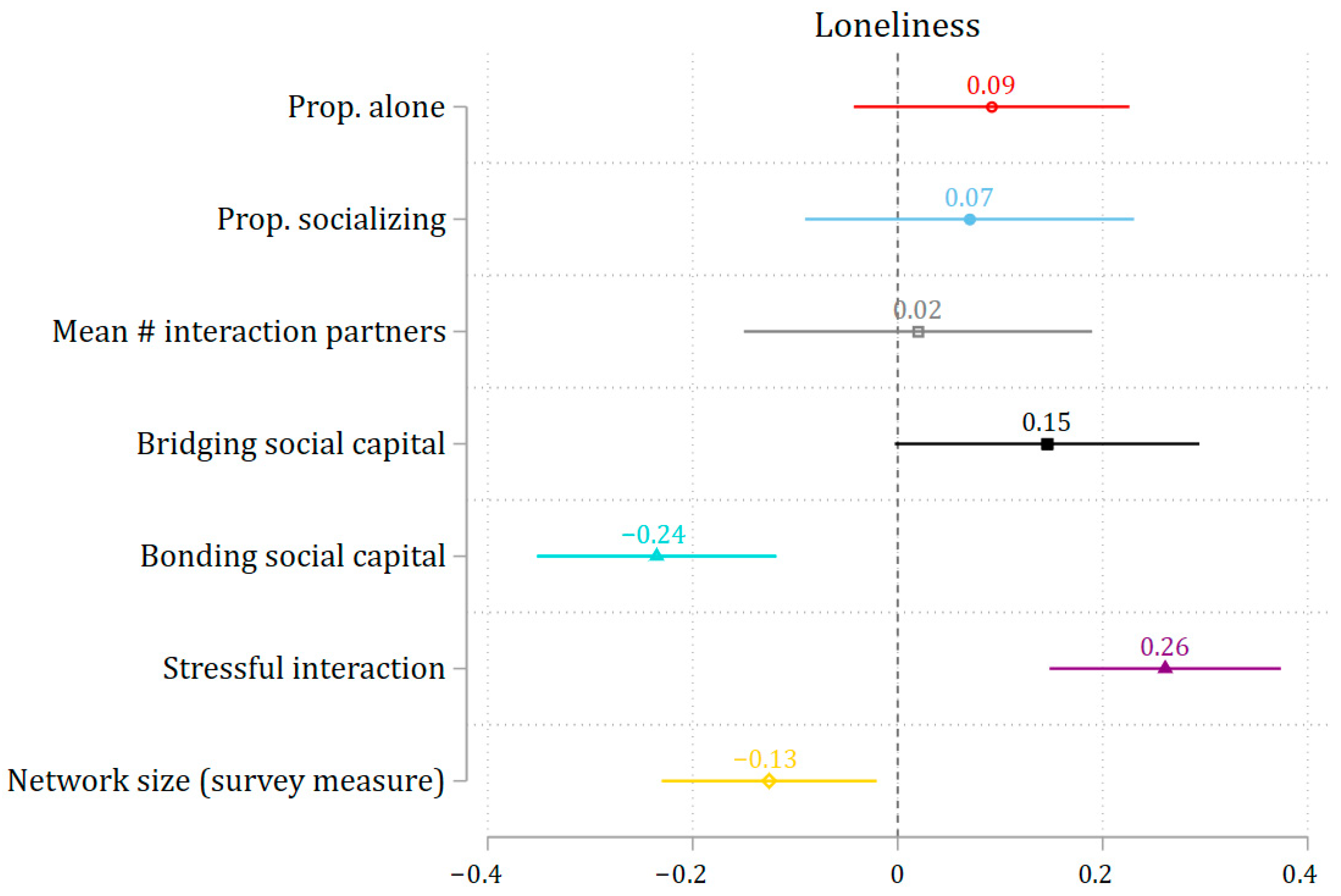

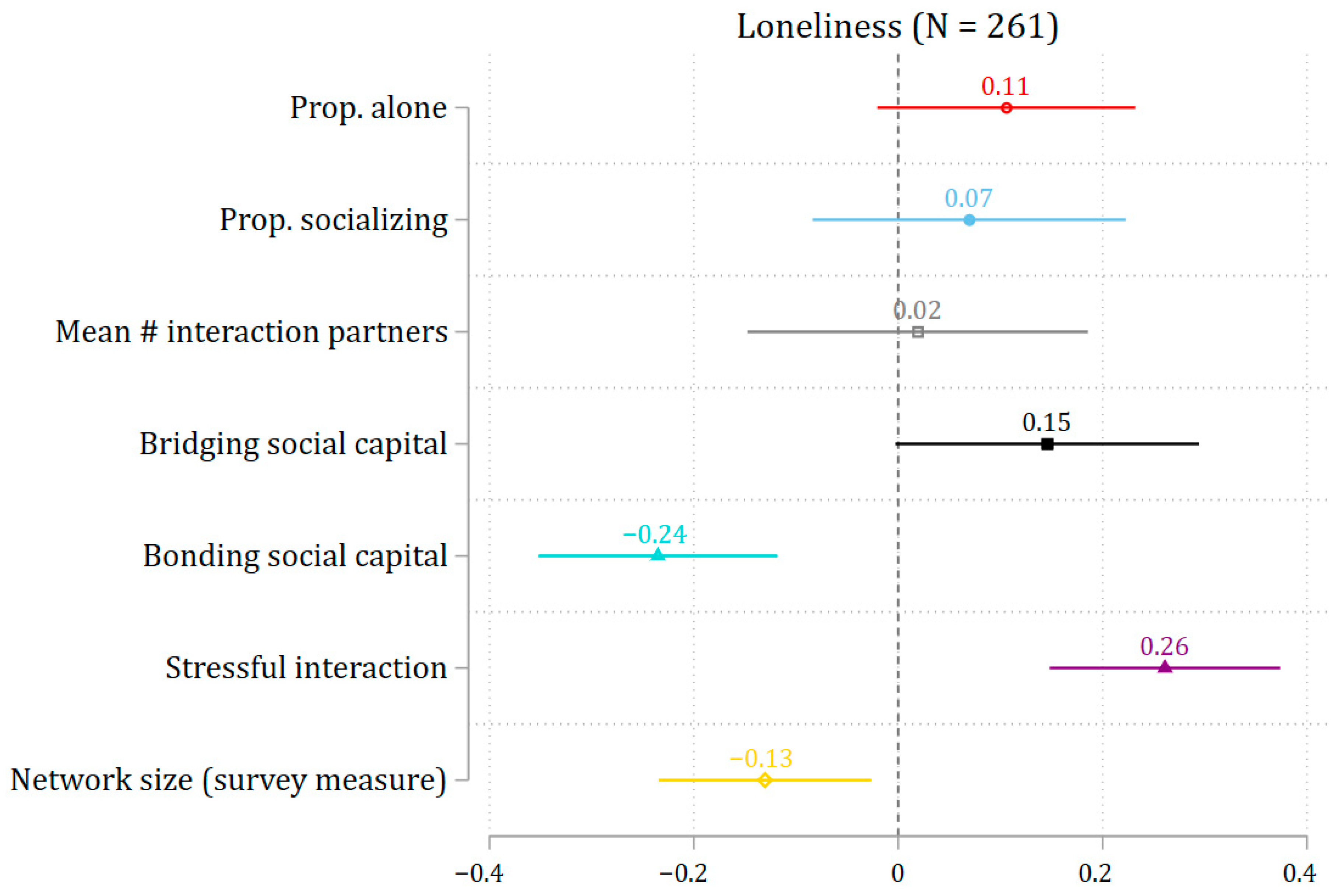

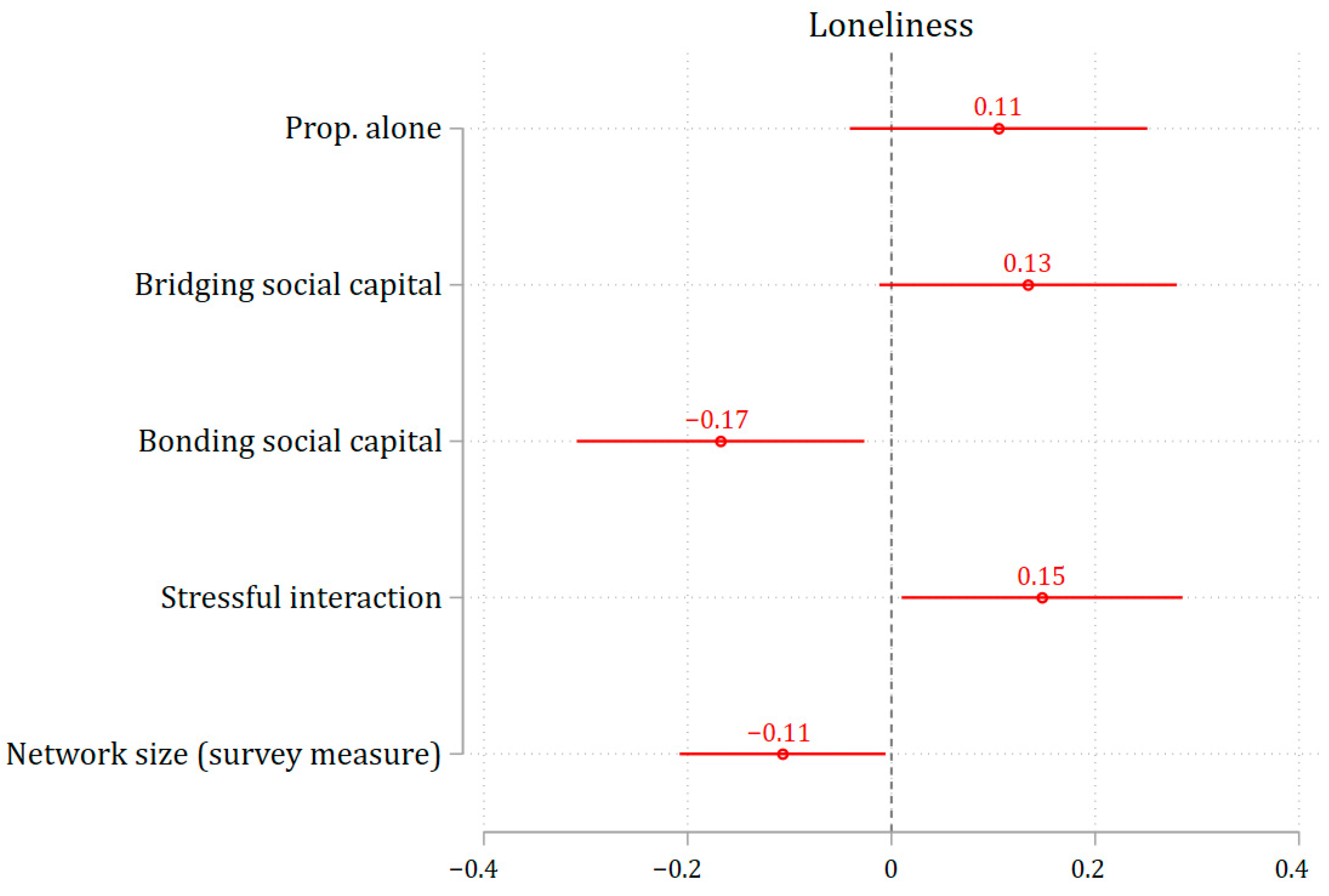

3.1. Dimensions of Social Interaction Linked to Loneliness

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peplau, L.A.; Goldston, S.E. Preventing the Harmful Consequences of Severe and Persistent Loneliness; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health: Rockville, MD, USA, 1984.

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, N.C.; Choi, H.; Wei, M.Y.; Langa, K.M.; Chopra, V. The relationship of loneliness to end-of-life experience in older Americans: A cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, L.; Kang, D.-H.; Branson, S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gao, Y.; Han, Z.; Yu, Y.; Long, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Y.; Pei, B.; Cao, Y.; Ye, J.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 90 cohort studies of social isolation, loneliness and mortality. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerman, K.L.; Ng, Y.T.; Zhang, S.; Britt, K.; Colera, G.; Birditt, K.S.; Charles, S.T. Living Alone During COVID-19: Social Contact and Emotional Well-being Among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e116–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczynski, A.M.; Halvorson, M.A.; Slater, L.R.; Kanter, J.W. The effect of social interaction quantity and quality on depressed mood and loneliness: A daily diary study. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2022, 39, 734–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.D.; Dulmen, M.H.M.V. Oxford Handbook of Methods in Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, L.D.; Davis, M.C. Loneliness, daily pain, and perceptions of interpersonal events in adults with fibromyalgia. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhaoyang, R.; Harrington, K.D.; Scott, S.B.; Graham-Engeland, J.E.; Sliwinski, M.J. Daily Social Interactions and Momentary Loneliness: The Role of Trait Loneliness and Neuroticism. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartsen, M.; Jylhä, M. Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. Eur. J. Ageing 2011, 8, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthmuller, S. Loneliness among older adults in Europe: The relative importance of early and later life conditions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Z.; Tomás, J.M.; Sentandreu-Mañó, T.; Fernández, I.; Pla-Sanz, N. Social participation, loneliness, and physical inactivity over time: Evidence from SHARE. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging. 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Tang, F. The Role of Solitary Activity in Moderating the Association between Social Isolation and Perceived Loneliness among U.S. Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2022, 65, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Fingerman, K.L.; Birditt, K.S. Loneliness and Mode of Social Contact in Late Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 2024, 79, gbae115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T. Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support, and Health; Ichiro, K., Berkman, L.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, R.S. The network structure of social capital. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.R.; Wilson, R.S.; Kamenetsky, J.M.; Barnes, L.L.; Bienias, J.L.; Bennett, D.A. Social engagement and cognitive function in old age. Exp. Aging Res. 2009, 35, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Roth, A.R.; Perry, B.L. A latent variable approach to measuring bridging social capital and examining its association to older adults’ cognitive health. Soc. Neurosci. 2021, 16, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, B. Good health and the bridging of structural holes. Soc. Netw. 2009, 31, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Feeley, T.H. Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2014, 31, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, E.M.; Restrepo, A.; Faig, K.E.; Raja, S.; Dimitroff, S.J.; Smith, K.E.; Norman, G.J. Loneliness Is Associated with Decreased Support and Increased Strain Given in Social Relationships. Psychophysiology 2025, 62, e70105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Hülür, G. The Role of Relationship Conflict for Momentary Loneliness and Affect in the Daily Lives of Older Couples. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2023, 40, 2033–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.R. Ecological Momentary Assessments in Sociology. Soc. Curr. 2024, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.R.; Peng, S.; Jarin, J.N.; Qu, T.; Fekete, M.; Perry, B.L. Social Environment and Cognitive Health in Urban and Rural Areas (SECHURA). OSF 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlin, J.; McKee, K.J.; Lennartsson, C.; Dahlberg, L. Quantity and quality of social relationships and their associations with loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.M.; Strader, L.C.; Pratt, J.G.; Maiese, D.; Hendershot, T.; Kwok, R.K.; Hammond, J.A.; Huggins, W.; Jackman, D.; Pan, H.; et al. The PhenX Toolkit: Get the Most from Your Measures. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.L.; Pescosolido, B.A.; Borgatti, S.P. Egocentric Network Analysis: Foundations, Methods, and Models; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, R.I.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Harrah, C.H.; Chance, J.M.; Filos, S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J. Gerontol. 1982, 37, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degroote, L.; DeSmet, A.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Dyck, D.; Crombez, G. Content validity and methodological considerations in ecological momentary assessment studies on physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Braak, P.; van Tienoven, T.P.; Minnen, J.; Glorieux, I. Data Quality and Recall Bias in Time-Diary Research: The Effects of Prolonged Recall Periods in Self-Administered Online Time-Use Surveys. Sociol. Methodol. 2023, 53, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, N.E.G.; Menec, V.H. Loneliness and social isolation of older adults: Why it is important to examine these social aspects together. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Lonely hearts: Psychological perspectives on loneliness. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1999, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay Jr, E.P.; Cutri, J.; Teneva, N. How loneliness undermines close relationships and persists over time: The role of perceived regard and care. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 127, 609–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajrouch, K.J.; Antonucci, T.C.; Janevic, M.R. Social networks among Blacks and Whites the interaction between race and age. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2001, 56, S112–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.S.; Beresford, L. Changes in support networks in late middle age: The extension of gender and educational differences. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2015, 70, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean/Proportion | SD | Range | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 0.51 | 0.46 | 272 | |

| Age | 66.10 | 7.70 | 55–88 | 272 |

| White | 0.87 | 0.28 | 272 | |

| Education | 272 | |||

| Less than HS | 0.05 | |||

| HS or GED | 0.27 | |||

| Some college | 0.24 | |||

| College | 0.43 | |||

| Employed | 0.40 | 0.48 | 272 | |

| Functional activity limitation | 0.48 | 0.50 | 272 | |

| Network size | 5.02 | 2.81 | 1–19 | 272 |

| Loneliness | 1.46 | 0.62 | 1.00–3.00 | 272 |

| EMA measures | ||||

| Prop. alone | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0–1 | 272 |

| Prop. socializing | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0–0.57 | 272 |

| Mean # interaction partners | 0.93 | 0.73 | 0–5 | 272 |

| Bridging social capital | 4.87 | 1.83 | 1.00–9.42 | 261 |

| Bonding social capital | 7.47 | 1.31 | 3.20–10.00 | 261 |

| Stressful interaction | 2.49 | 1.35 | 1.00–8.00 | 261 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, S.; Roth, A.R. Quality over Quantity: The Association Between Daily Social Interactions and Loneliness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091411

Peng S, Roth AR. Quality over Quantity: The Association Between Daily Social Interactions and Loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091411

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Siyun, and Adam R. Roth. 2025. "Quality over Quantity: The Association Between Daily Social Interactions and Loneliness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091411

APA StylePeng, S., & Roth, A. R. (2025). Quality over Quantity: The Association Between Daily Social Interactions and Loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091411