Traditional Gender Role Attitudes and Job-Hunting in Relation to Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Women in Emerging Adulthood

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review and Hypotheses

1.1.1. Well-Being

1.1.2. Gender Differences in Employment

1.1.3. Social Role Theory

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement Statement

2.5. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, W.R.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Swider, B.W. Employee job search: Toward an understanding of search context and search objectives. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 129–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumb, P.L.; Lampert, T. Women, work, and well-being 1950–2000: A review and methodological critique. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravi, F.K.; Navidian, A.; Rigi, S.N.; Montazeri, A. Comparing health-related quality of life of employed women and housewives: A cross-sectional study from southeast Iran. BMC Womens Health 2012, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, D. Employment status and well-being among young individuals: Why do we observe cross-country differences? Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedikli, C.; Miraglia, M.; Connolly, S.; Bryan, M.; Watson, D. The relationship between unemployment and well-being: An updated meta-analysis of longitudinal evidence. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2023, 32, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Jalil, N.I.; Tan, S.A.; Ibharim, N.S.; Musa, A.Z.; Ang, S.H.; Mangundjaya, W.L. The relationship between job insecurity and psychological well-being among Malaysian precarious workers: Work-life balance as a mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, M.; Dudel, C.; Werding, M. Maternal health, well-being, and employment transitions: A longitudinal comparison of partnered and single mothers in Germany. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 114, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, L.; Butterworth, P. The role of financial hardship, mastery and social support in the association between employment status and depression: Results from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaydarifard, S.; Smith, S.S.; Mann, D.; Rossa, K.R.; Salehi, E.N.; Srinivasan, A.G.; Soleimanloo, S.S. Precarious employment and associated health and social consequences: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2023, 47, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moortel, D.; Vandenheede, H.; Vanroelen, C. Contemporary employment arrangements and mental well-being in men and women across Europe: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hult, M.; Kaarakainen, M.; De Moortel, D. Values, health and well-being of young Europeans not in employment, education or training (NEET). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Youth Foundation. 2017 Global Youth Wellbeing Index; International Youth Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.youthindex.org/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2022 Survey on Employment Trends; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. Databook of International Labour Statistics 2022; JILPT: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Belete, A.K. Turnover intention influencing factors of employees: An empirical work review. J. Entrep. Organ. Manag. 2018, 7, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.C.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, X.D.; Dai, X.X.; Tsai, F.S. The impact of inclusive talent development model on turnover intention of new generation employees: The mediation of work passion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.-T.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Nguyen, N.-T. Determinants influencing job-hopping behavior and turnover intention: An investigation among Gen Z in the marketing field. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kaltiainen, J.; Hakanen, J.J. Overbenefitting, underbenefitting, and balanced: Different effort–reward profiles and their relationship with employee well-being, mental health, and job attitudes among young employees. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1020494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Dias, Á.; Pereira, L.F. Determinants of employee intention to stay: A generational multigroup analysis. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 32, 1389–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, B.A.; Judge, T.A. Emotional responses to work–family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chang, T.T.; Kao, S.F.; Cooper, C.L. Do gender and gender role orientation make a difference in the link between role demands and family interference with work for Taiwanese workers? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, New York, 18 December 1979; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Act on Securing, Etc. of Equal Opportunity and Treatment Between Men and Women in Employment; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, Gender Equality Bureau. White Paper on Gender Equality 2023; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). SIGI 2023 Global Report: Gender Equality in Times of Crisis, Social Institutions and Gender Index; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, M.; Kamo, Y. Gender differences in happiness: The effects of marriage, social roles, and social support in East Asia. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancea, M.; Utzet, M. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: A scoping study on social determinants. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Social Role Theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 458–476. [Google Scholar]

- Helou, L.E.; Ayoub, M. Relations between traditional gender-role attitudes, personality traits, and preference for the stay-at-home mother role in Lebanon. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2024; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shiotani, T.M.; Yamakami, K.; Matsumoto, F.; Ishimaru, K.; Ooya, M. Development of the KIT version of PERMA Profiler (1): Necessity of a measure of positive facets for students and basic psychometrics. Proc. Jpn. Soc. Eng. Educ. 2015, 0, 430–431. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Kawakami, N.; Shiotani, T.; Adachi, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Imamura, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Yamagami, F.; Fusejima, A.; Muraoka, T.; et al. The Japanese Workplace PERMA-Profiler: A validation study among Japanese workers. J. Occup. Health 2018, 60, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M.L. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, K. A study on feminine gender role stressors among female workers: Development of a gender role stressor scale for women and examining demographic differences. J. Health Psychol. Res. 2018, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibáñez, I.; Fortes, D.; Díaz, A. Gender differences in psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.A.; Fink, R.S. Attachment, social support satisfaction, and well-being during life transition in emerging adulthood. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 43, 1034–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, S.; Delfabbro, P.; Anderson, S.; Winefield, A. Leisure activities and adolescent psychological well-being. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; McNeely, E.; Weziak-Bialowolska, D.; Ryan, K.A.; Mooney, K.D.; Cowden, R.G.; VanderWeele, T.J. Demographic predictors of complete well-being. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angela, S.; Fonseca, G.; Lep, Ž.; Li, L.J.; Serido, J.; Vosylis, R.; Crespo, C.; Relvas, A.P.; Zupančič, M.; Lanz, M. Profiles of emerging adults’ resilience facing the negative impact of COVID-19 across six countries. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 43, 14113–14125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Pers. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshio, A.; Abe, S.; Cutrone, P. Development, reliability, and validity of the Japanese version of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI-J). Jpn. J. Pers. 2012, 21, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sola, H.; Salazar, A.; Dueñas, M.; Ojeda, B.; Failde, I. Nationwide cross-sectional study of the impact of chronic pain on an individual’s employment: Relationship with the family and the social support. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, H.; Gondo, Y.; Masui, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Kawai, C.; Otsuka, R.; Ogawa, M.; Takayama, M.; Imuta, H.; Suzuki, T. Development of a Japanese version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support and examination of its validity and reliability. J. Health Welf. Stat. 2007, 54, 26–33. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, D.; Chandola, R. Difference in perceiving role of man and woman among Gen X and Gen Z in current society. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023, 12, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JILPT). Job Turnover Status of Young People and Career Development After Leaving the Job (Survey on Young People’s Ability Development and Retention in the Workplace); JILPT Survey Series No.164; JILPT: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B.; Fleischmann, M.; Head, J.; McMunn, A.; Stafford, M. Work–family conflict and work exit in later career stage. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, M.; Stickley, A.; Takemura, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Oka, M.; Ojima, T.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Community gender norms, mental health, and suicide ideation and attempts among older Japanese adults: A cross-sectional study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2023, 36, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, C.S.; Spak, L.; Hensing, G. Multiple social roles, health, and sickness absence: A five-year follow-up study of professional women in Sweden. Women Health 2012, 52, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Ng, P.Y.N.; Chiu, R.; Li, S.S.; Klassen, R.M.; Su, S.S. Criteria for adulthood, resilience, and self-esteem among emerging adults in Hong Kong: A path analysis approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kobayashi, R.; Oda, M.; Noritake, Y.; Nakashima, K. Does shift-and-persist strategy buffer career choice anxiety and affect career exploration? BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanimoğlu, E. A mediation and moderation model for life satisfaction: The role of social support, psychological resilience, and gender. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n [%] or Mean [SD] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (range:18–29) | 24.23 | [3.23] | |

| Occupation | Student | 40 | [30.30] |

| Working adult | 92 | [69.70] | |

| Household situation | Living alone | 47 | [35.61] |

| Living with family | 75 | [56.82] | |

| Other | 10 | [7.58] | |

| Present illness | None | 66 | [50.00] |

| One or more | 66 | [50.00] | |

| Self-assessed living conditions | Very comfortable | 10 | [7.58] |

| Somewhat comfortable | 29 | [21.97] | |

| Normal | 65 | [49.24] | |

| Somewhat difficult | 22 | [16.67] | |

| Very difficult | 6 | [4.55] | |

| Personality | Extraversion | 8.11 | [3.01] |

| Agreeableness | 10.29 | [2.41] | |

| Conscientiousness | 6.73 | [2.70] | |

| Neuroticism | 9.08 | [2.66] | |

| Openness to experience | 8.07 | [2.84] | |

| Perceived social support (range: 7–49) | 39.01 | [8.17] | |

| Well-being (range: 0–10) | 6.10 | [1.61] | |

| Job-hunting | No | 97 | [73.48] |

| Yes | 35 | [26.52] | |

| Gender role attitudes (range:12–60) * | 53.11 | [8.69] | |

| Crude | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p-Value | B | 95% CI | p-Value | |

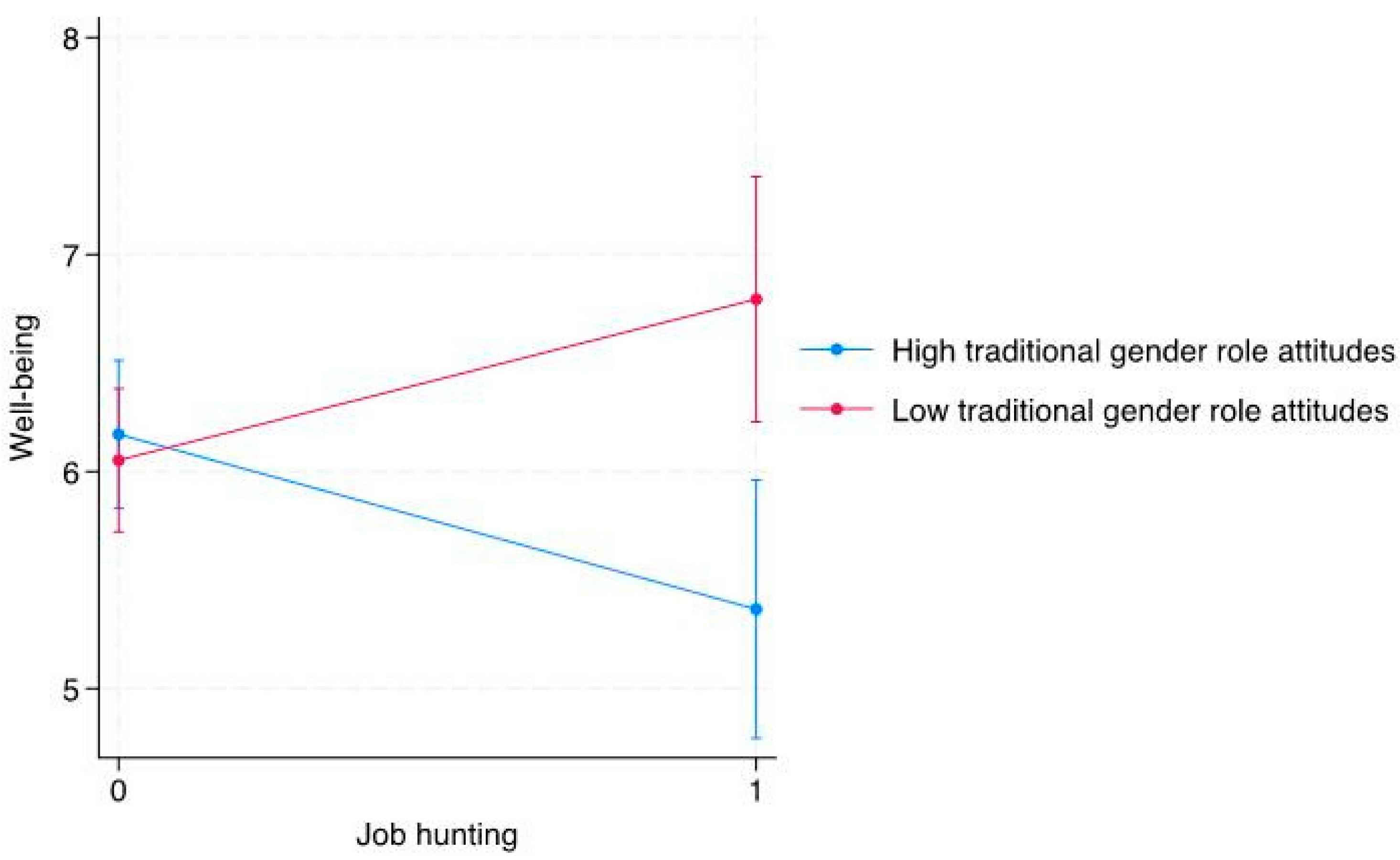

| 1 Job-hunting | 0.18 | [−0.46–0.81] | 0.58 | −0.81 | [−1.52–−0.10] | 0.03 |

| 2 Gender-role attitudes | −0.12 | [−0.60–0.36] | 0.62 | |||

| 1 × 2 interactions | 1.55 | [0.58–2.51] | 0.00 | |||

| Age | 0.06 | [−0.02–1.43] | 0.15 | |||

| Occupation | 0.82 | [0.21–1.43] | 0.01 | |||

| Household situation | ||||||

| Living alone (ref.) | - | - | - | |||

| Living with family | 0.14 | [−0.29–0.57] | 0.52 | |||

| Other | −0.19 | [−1.00–0.62] | 0.64 | |||

| Present illness | 0.30 | [−0.11–0.71] | 0.16 | |||

| Self-assessed living conditions | ||||||

| Very comfortable (ref.) | - | - | - | |||

| Somewhat comfortable | −0.70 | [−1.56–0.16] | 0.11 | |||

| Normal | −0.42 | [−1.23–0.39] | 0.31 | |||

| Somewhat difficult | −0.85 | [−1.76–0.05] | 0.06 | |||

| Very difficult | 0.21 | [−1.05–1.46] | 0.74 | |||

| Personality | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.04 | [−0.03–0.12] | 0.26 | |||

| Agreeableness | 0.02 | [−0.07–0.11] | 0.60 | |||

| Conscientiousness | 0.07 | [−0.01–0.15] | 0.08 | |||

| Neuroticism | −0.13 | [−0.22–−0.04] | 0.00 | |||

| Openness to experience | 0.09 | [0.02–0.17] | 0.00 | |||

| Perceived social support | 0.11 | [0.09–0.14] | <0.00 | |||

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.52 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kobayashi, Y.; Imamatsu, Y.; Arimoto, A.; Takase, K.; Fusejima, A.; Tsuno, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Sannnomiya, M.; Miyazaki, T. Traditional Gender Role Attitudes and Job-Hunting in Relation to Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Women in Emerging Adulthood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091385

Kobayashi Y, Imamatsu Y, Arimoto A, Takase K, Fusejima A, Tsuno K, Sugiyama T, Sannnomiya M, Miyazaki T. Traditional Gender Role Attitudes and Job-Hunting in Relation to Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Women in Emerging Adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091385

Chicago/Turabian StyleKobayashi, Yumiko, Yuki Imamatsu, Azusa Arimoto, Kenkichi Takase, Ayumi Fusejima, Kanami Tsuno, Takashi Sugiyama, Masana Sannnomiya, and Tomoyuki Miyazaki. 2025. "Traditional Gender Role Attitudes and Job-Hunting in Relation to Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Women in Emerging Adulthood" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091385

APA StyleKobayashi, Y., Imamatsu, Y., Arimoto, A., Takase, K., Fusejima, A., Tsuno, K., Sugiyama, T., Sannnomiya, M., & Miyazaki, T. (2025). Traditional Gender Role Attitudes and Job-Hunting in Relation to Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Women in Emerging Adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091385