Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Background/Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Screening Procedure

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Charting and Analysis

2.7. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

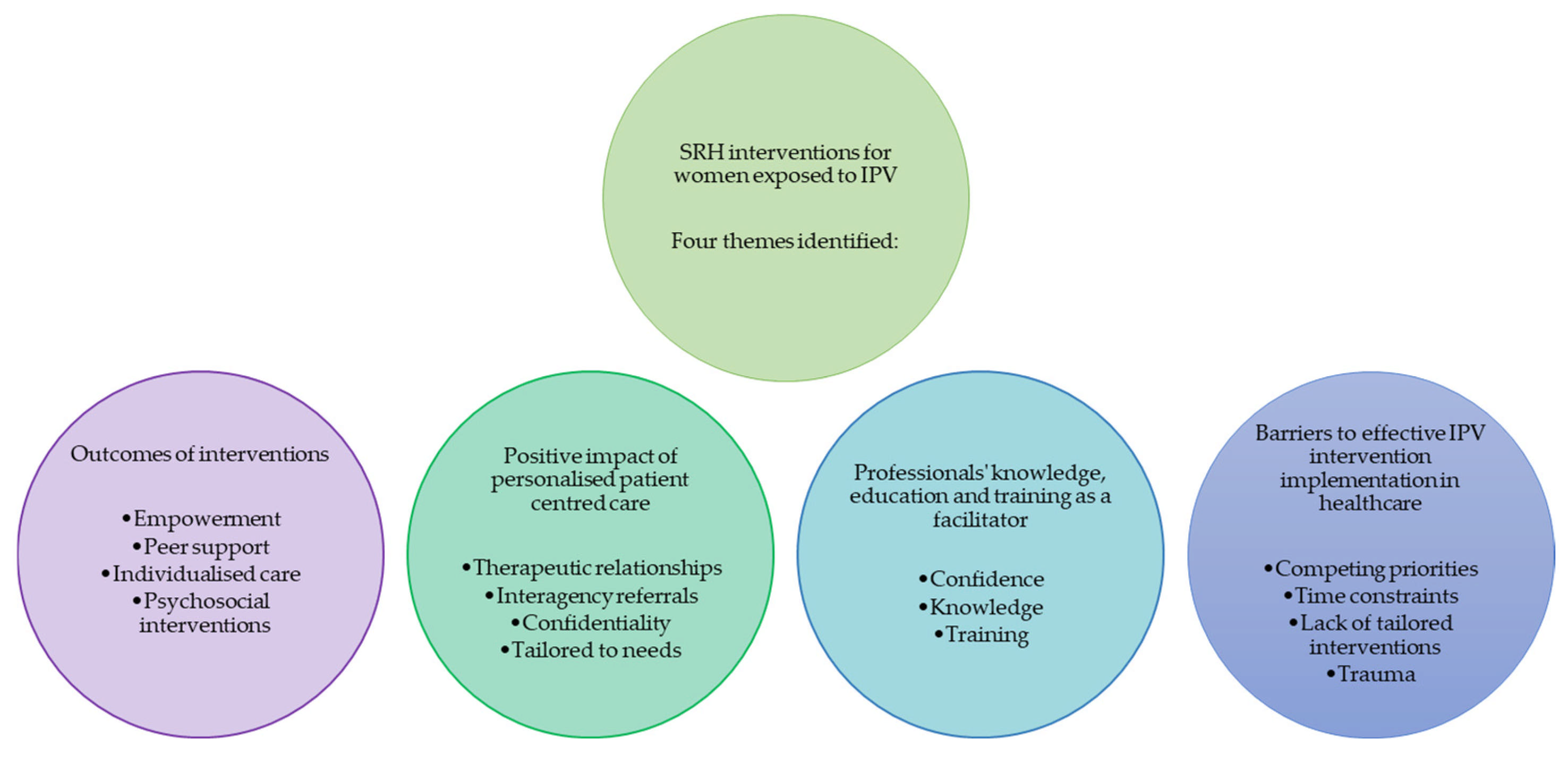

3.2. Identified Themes

3.3. Outcomes of Interventions

3.4. Positive Impact of Personalised and Patient-Centred Care

3.5. Professionals’ Knowledge, Education and Training as a Facilitator

3.6. Barriers to Effective IPV Intervention Implementation in Healthcare

4. Discussion

4.1. Outcomes of Interventions

4.2. Positive Impact of Personalised and Patient-Centred Care

4.3. Facilitators

4.4. Barriers

4.5. Strengths

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- East, L.; Terry, D.; Viljoen, B.; Hutchinson, M. Intimate partner violence and sexual and reproductive health outcomes of women: An Australian population cohort study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2025, 44, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, L.; Hollingdrake, O.; Currie, J. Social determinant factors and access to health care for women experiencing domestic and family violence: Qualitative synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.S.; Silberberg, M.R.; Brown, A.J.; Yaggy, S.D. Health needs and barriers to healthcare of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J. Women’s Health 2007, 16, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, M.E.; Makaroun, L.; Tuepker, A.; True, G.; Montgomery, A.E.; Iverson, K. Middle-aged women’s experiences of intimate partner violence screening and disclosure: “It’s a private matter. It’s an embarrassing situation”. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2655–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, M.; Gannon, M.; Stanley, N.; Cosgrove, K.; Feder, G. ‘You certainly don’t go back to the doctor once you’ve been told, “I’ll never understand women like you.”’ Seeking candidacy and structural competency in the dynamics of domestic abuse disclosure. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.E.; Crowe, A.; Overstreet, N.M. Sources and components of stigma experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanslow, J.L.; Robinson, E.M. Physical injuries resulting from intimate partner violence and disclosure to healthcare providers: Results from a New Zealand population-based study. Inj. Prev. 2011, 17, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.; Manhire, K.; Marshall, B. Prevalence of intimate partner violence disclosed during routine screening in a large general practice. J. Prim. Health Care 2015, 7, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lichtenstein, B. Domestic violence in barriers to health care for HIV-positive women. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2006, 20, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, A.; Yavan, T.; Şahiner, G.; Kılıç, A. Domestic violence and woman’s reproductive health: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.C.; Bencomo, C.; Rees, S.; Ventevogel, P.; Likindikoki, S.; Nemiro, A.; Bonz, A.; Mbwambo, J.K.; Tol, W.A.; McGovern, T.M. Multilevel determinants of integrated service delivery for intimate partner violence and mental health in humanitarian settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, M.; Mcmurray, A.; Rowe, J.; Wallis, M. Domestic violence, health and health care: Women’s accounts of their experiences. Contemp. Nurse 2006, 21, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, J.; Fisher, C. Health professionals’ responses to women’s disclosure of domestic violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 2363–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingdrake, O.; Saadi, N.; Alban Cruz, A.; Currie, J. Qualitative study of the perspectives of women with lived experience of domestic and family violence on accessing healthcare. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S. Intersectional Trauma-Informed Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Services: Narrowing the Gap between IPV Service Delivery and Survivor Needs. J. Fam. Violence 2019, 34, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, L.; Hutchinson, M. Sexual violence matters: Nurses must respond. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.; Hammarberg, K.; Romero, L.; Fisher, J. Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee-like backgrounds: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, A.G.; Downing, C.; Temane, A.; Hastings-Tolsma, M. Compassion fatigue in nurses: A metasynthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4364–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Chen, L.; Feng, F.; Okoli, C.T.; Tang, P.; Zeng, L.; Jin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. The prevalence of com-passion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, N.; Cameron, J.; Baloch, S.; Tarzia, L.; Hegarty, K. Health practitioners’ perceptions of structural barriers to the identification of intimate partner abuse: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanslow, J. Intimate partner violence and women’s reproductive health. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2017, 27, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annu. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Reproductive Health Strategy: To Accelerate Progress Towards the Attainment of International Development Goals and Targets; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.A. Systematic and Nonsystematic Reviews: Choosing an Approach. In Healthcare Simulation Research: A Practical Guide; Nestel, D., Hui, J., Kunkler, K., Scerbo, M.W., Calhoun, A.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Ed.; APA Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E.; Decker, M.R.; McCauley, H.L.; Tancredi, D.J.; Levenson, R.R.; Waldman, J.; Schoenwald, P.; Silverman, J.G. A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion. Contraception 2011, 83, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrani, V.B.; McCabe, B.E.; Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M.; Florom-Smith, A.; Peragallo, N. Participation in SEPA, a sexual and relational health intervention for Hispanic women. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, J.; Boyce, S.C.; Undie, C.C.; Liambila, W.; Wendoh, S.; Pearson, E.; Johns, N.E.; Silverman, J.G. Effects of a clinic-based reproductive empowerment intervention on proximal outcomes of contraceptive use, self-efficacy, attitudes, and awareness and use of survivor services: A cluster-controlled trial in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2023, 31, 2227371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.V.; Munas, M.; Colombini, M.; d’Oliveira, A.F.; Pereira, S.; Shrestha, S.; Rajapakse, T.; Shaheen, A.; Rishal, P.; Alkaiyat, A.; et al. Interventions in sexual and reproductive health services addressing violence against women in low-income and middle-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, B.; Gielen, A. Integrated Multicomponent Interventions for Safety and Health Risks Among Black Female Survivors of Violence: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, B.; Mani, S.S.; Kaduluri, V.P.S. Integrated domestic violence and reproductive health interventions in India: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmelin, T.; Raible, C.A.; Dick, R.; Kukke, S.; Miller, E. Integrating Reproductive Health Services Into Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Victim Service Programs. Violence Against Women 2018, 24, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; McCauley, H.L.; Decker, M.R.; Levenson, R.; Zelazny, S.; Jones, K.A.; Anderson, H.; Silverman, J.G. Implementation of a Family Planning Clinic-Based Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion Intervention: Provider and Patient Perspectives. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2017, 49, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, M.R.; Flessa, S.; Pillai, R.V.; Dick, R.N.; Quam, J.; Cheng, D.; McDonald-Mosley, R.; Alexander, K.A.; Holliday, C.N.; Miller, E. Implementing Trauma-Informed Partner Violence Assessment in Family Planning Clinics. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, M.; El-Mohandes, A.A.E.; El-Khorazaty, M.N.; Gantz, M.G. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence in pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Deosthali, P.B.; Rege, S. Effectiveness of a counselling intervention implemented in antenatal setting for pregnant women facing domestic violence: A pre-experimental study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Donta, B.; Shahina, B. Intervention to reduce partner violence and enhance contraceptive use among women in a low-income community in Mumbai, India. Indian Soc. Study Reprod. Fertil. Newsl. 2020, 25, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Saggurti, N.; Battala, M.; Nair, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Naik, D.D.; Abramovitz, D.; Silverman, J.G.; Balaiah, D. Randomized controlled trial to test the RHANI Wives HIV intervention for women in India at risk for HIV from husbands. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 3066–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggurti, N.; Nair, S.; Silverman, J.G.; Naik, D.D.; Battala, M.; Dasgupta, A.; Balaiah, D.; Raj, A. Impact of the RHANI Wives intervention on marital conflict and sexual coercion. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2014, 126, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Harb, M.; Satyen, L.; Davies, M. s-CAPE trauma recovery program: The need for a holistic, trauma- and violence-informed domestic violence framework. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1404599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, L.; Norman, R.; Devine, A.; Feder, G.; Taft, A.J.; Hegarty, K.L. Cost-Effectiveness of Health Care Interventions to Address Intimate Partner Violence: What Do We Know and What Else Should We Look for? Violence Against Women 2011, 17, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, P.; Tandon, S.; Khanna, A. Virtual and essential—Adolescent SRHR in the time of COVID-19. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1831136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.L.; Fulda, K.G.; Grace, J.; Galvin, A.M.; Spence, E.E. The Implementation of an Interpersonal Violence Screening Program in Primary Care Settings: Lessons Learned. Health Promot. Pract. 2022, 23, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Odah, H.; Said, N.B.; Nair, S.C.; Allsop, M.J.; Currow, D.C.; Salah, M.S.; Hamad, B.A.; Elessi, K.; Alkhatib, A.; ElMokhallalati, Y.; et al. Identifying barriers and facilitators of translating research evidence into clinical practice: A systematic review of reviews. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e3265–e3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbe, E.; Harmon, S.; Van den Bergh, R.; Degomme, O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Yuen, K.H.; Yuk, H.; Pang, P.; Humphreys, J.; Bullock, L. Effect of an Advocacy Intervention on Mental Health in Chinese Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2010, 304, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutty, L. Chapter Sixteen: Identifying, Assessing, and Counselling Male Intimate Partner Violence Perpetrators and Abused Women. In Cruel but Not Unusual: Violence in Families in Canada; Alaggia, R., Vine, C., Eds.; Wilfrid Laurier University Press: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 519–552. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, L.; Taket, A.; Valpied, J.; Hegarty, K. Receiving care for intimate partner violence in primary care: Barriers and enablers for women participating in the weave randomised controlled trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 160, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, M.; Ball, T.; Rajah, V. Peer Support Work in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024, 25, 4261–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Johnson, E.; Feder, G.; Campbell, J.; Konya, J.; Perôt, C. Perceptions of Peer Support for Victim-Survivors of Sexual Violence and Abuse: An Exploratory Study With Key Stakeholders. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP14036–NP14065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubovich, A.R.; Bartsch, A.; Metheny, N.; Gesink, D.; O’Campo, P. Housing interventions for women experiencing intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e23–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard-Eckrich, D.; Henry, B.F.; Sardana, S.; Thomas, B.V.; Richer, A.; Hunt, T.; Chang, M.; Johnson, K.; Gilbert, L. Evidence of Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Black Women Under Community Supervision in New York City: A Plea for Culturally Tailored Intimate Partner Violence Interventions. Women’s Health Rep. 2022, 3, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lirios, A.; Mullens, A.B.; Daken, K.; Moran, C.; Gu, Z.; Assefa, Y.; Dean, J.A. Sexual and reproductive health literacy of culturally and linguistically diverse young people in Australia: A systematic review. Cult. Health Sex. 2024, 26, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.; Walker, T.; Hamer, J.; Broady, T.; Kean, J.; Ling, J.; Bear, B. Developing LGBTQ Programs for Perpetrators and Victims/Survivors of Domestic and Family Violence (Research Report Octeber 2020); Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, C.; Dunlea, R.R. The Prosecution of Same-Sex Intimate Partner Violence Cases. J. Interpers. Violence 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.M. Demedicalizing the aftermath of sexual assault: Toward a radical humanistic approach. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 61, 939–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathen, C.N.; Mantler, T. Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care: Orienting Intimate Partner Violence Interventions to Equity. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2022, 9, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, B.J. Growing Forward: Best-Practice(s) in Client-Centred Service(s) for Those Experiencing and Using Intimate Partner Violence; University of Regina: Regina, SK, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vazquez Corona, M.; Odiase, O.J.; Wilson, A.N.; Sudhinaraset, M.; Diamond-Smith, N.; Berryman, J.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Afulani, P.A. Strategies to reduce stigma and discrimination in sexual and reproductive healthcare settings: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murvartian, L.; Matías-García, J.A.; Saavedra-Macías, F.J.; Crowe, A. A Systematic Review of Public Stigmatization Toward Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024, 25, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.E.; Risser, L.; Miller-Walfish, S.; Marjavi, A.; Ali, A.; Segebrecht, J.; Branch, T.; Dawson, S.; Miller, E. Policy and Systems Change in Intimate Partner Violence and Human Trafficking: Evaluation of a Federal Cross-Sector Initiative. J. Women’s Health 2023, 32, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor-Terry, C.; Burton, D.; Gowda, T.; Laing, A.; Chang, J.C. Challenges of seeking reproductive health care in people experiencing intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP5167–NP5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmerski, T.; McCauley, H.L.; Jones, K.; Borrero, S.; Silverman, J.G.; Decker, M.R.; Tancredi, D.; Miller, E. Use of reproductive and sexual health services among female family planning clinic clients exposed to partner violence and reproductive coercion. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, A.B.; Duyker, J.; Brownlow, C.; Lemoire, J.; Daken, K.; Gow, J. Point-of-care testing (POCT) for HIV/STI targeting MSM in regional Australia at community ‘beat’ locations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachor, H.; Chang, J.C.; Zelazny, S.; Jones, K.A.; Miller, E. Training reproductive health providers to talk about intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion: An exploratory study. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, N.; Hooker, L.; Reisenhofer, S.; Di Tanna, G.L.; García-Moreno, C. Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, CD012423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambikile, J.S.; Leshabari, S.; Ohnishi, M. Curricular Limitations and Recommendations for Training Health Care Providers to Respond to Intimate Partner Violence: An Integrative Literature Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, E.M.; Chávez-Baray, S.M.; Martínez, O.; Aguirre-Polanco, A. Exploring intimate partner violence and sexual health needs in the southwestern united states: Perspectives from health and human services workers. Health Soc. Work. 2016, 41, e29–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolaran, O.; OlaOlorun, F.M. A community-based intervention to challenge attitudes towards intimate partner violence: Results from a randomised community trial in rural South-West Nigeria. Rural Remote Health 2025, 25, 9269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohit, N.F.M.; Rashid, S.A.Z.A.; Fakuradzi, W.F.S.W.A.; Zaidi, N.A.A.; Haque, M. Exploring pathways from community involvement to empowerment in sexual and reproductive health: A public health perspective. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2024, 14, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying Ying, C.; Hairi, N.N.; Othman, S. Tools for Assessing Healthcare Providers’ Readiness to Respond to Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Violence 2024, 39, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, G.A.; Colon, R.; Gross, G.M.; Adams, L.J.; Bastian, L.A.; Iverson, K.M. Patient and provider barriers, facilitators, and implementation preferences of intimate partner violence perpetration screening. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Venturato, L.; Mijovic-Kondejewski, J.; Smith-MacDonald, L. Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 69, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Pollock, D.; Khalil, H.; Alexander, L.; Mclnerney, P.; Godfrey, C.; Peters, M.; Tricco, A. What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year | Title | Country | Aim | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Main Findings | Total Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decker et al., 2017 [42] | Implementing Trauma-Informed Partner Violence Assessment in Family Planning Clinics | USA | To “describe: (1) the uptake and impact of the ARCHES brief IPV/RC assessment and intervention as implemented in family planning clinics, and (2) feasibility and acceptability as experienced by providers and patients alike.” | Sequential mixed-methods | Quantitative: English-speaking women, ages 18–35, were recruited at two family planning health centres (urban vs. suburban) in the Baltimore area from January to April 2014. Qualitative: English-speaking and ages 18–35, patients and providers. | Not stated | 65% reported receiving intervention, with 31% receiving both components. Women with history of experiencing IPV had lower belief that providers care about patient safety (78% vs. 92%, p = 0.04). Intervention recipients felt supported that healthcare providers were concerned for their safety (91.9% vs. 73.9%; RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01–1.47), would know what to do if in an unhealthy relationship (90.7% vs. 67.4%; RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.09–1.66, and knew about resources (33.3% vs. 8.0%, RR 4.29, 95% CI 1.05–17.55). Qualitative feedback indicated IPV assessment was viewed as provider concern for recipients, the safety card supported assessment and discussion. | Quantitative—n = 132 (total 146 recruited but 14 excluded due to incomplete intervention) Qualitative—patient interviewed n = 26, providers interviewed n = 9 |

| Gmelin et al., 2018 [40] | Integrating Reproductive Health Services Into Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Victim Service Programs | USA | To assess “training for victim service agencies on integration of health services” -Feedback on ‘Project Connect’ -Processes of partnership building between IPV/SV agencies and health services following training -Barriers and facilitators to connecting clients to reproductive and sexual health services | Qualitative descriptive—thematic analysis | ‘Project Connect’ sites | Not stated | Referral pathways through partnerships enhanced the care women received through enabling private yet direct referral to healthcare services Training led to improved relationships with other health services, and staff feeling empowered to discuss reproductive health topics | Not stated |

| Lewis et al., 2022 [37] | Interventions in sexual and reproductive health services addressing violence against women in low-income and middle-income countries: a mixed-methods systematic review | Review—multiple | “To synthesise evidence on the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and barriers to responding to violence against women (VAW) in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).” | Mixed-methods systematic review | Studies that evaluated Violence against women interventions in SRH services in LMICs, women of reproductive age 15–49 years and recipients of healthcare, healthcare professionals | Children aged < 15 years, no intervention, systematic reviews | Total 26 studies—reported results had variable impact on women’s health and violence reoccurrence. 11 studies specified IPV as the violence type Interventions were grouped as: During routine sexual or reproductive health consultation; During routine consultation plus community engagement; and In addition to routine consultation. | 901 HCP 12,078 women |

| Miller et al., 2011 [34] | A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion | USA | To examine the “efficacy of a family planning clinic-based intervention to address intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion” | Cluster RCT Intervention occurred at visit, follow-up duration 12–24 weeks post baseline. | All English-and Spanish-speaking women (aged 16–29) who were attending family planning clinics were eligible for screening | Not stated | Women who reported IPV in past three months in intervention arm had 71% reduction in the odds of pregnancy coercion at follow-up compared to control clinics participants (0.29, 95% CI 0.09 −0.91). No significant change in past three months IPV reporting at follow-up for women from intervention or control clinics, regardless of baseline status of IPV. Women in intervention arm also reported stopping dating someone (p < 0.001) or stopping unhealthy or unsafe relationship (p = 0.013) at follow-up (stratified by IPV reported at baseline). | Eligible clients n = 1337. Agreed to participate n = 1207. Control N = 451, intervention N = 453. (90.3% participation rate) n = 906 women completed the baseline and follow-up survey (retention rate 75.1%). Details related to retention rate or management was not provided. |

| Miller et al., 2017 [41] | Implementation of a Family Planning Clinic-Based Partner Violence and Reproductive Coercion Intervention: Provider and Patient Perspectives | USA | To explore the perceptions of patients and providers who underwent the intervention | Qualitative descriptive study of participants from larger cluster RCT | Providers and administrators: All staff. Patients: Women aged 18 or older | Not stated | Administrators: Found training day feasible and had improved contact with local services. Providers: 11/18 staff believed intervention supported streamlined contraceptive counselling and was useful reminder to assess for partner violence and RC. Patients: Appreciated the information, some shared the information with others, and they felt supported and less isolated. | 23 clinic staff (18 providers, 5 administrators) 49 patients (one group) |

| Mitrani et al., 2017 [35] | Participation in SEPA, a Sexual and Relational Health Intervention for Hispanic Women | USA | To examine participant characteristics that are barriers and facilitators of engagement in the randomized trial conducted with Hispanic women in the United States | RCT (‘Health, Education, Prevention, and Self-Care’ arm) | Self-identified as Hispanic, aged 18–50 years, reporting sexual intercourse in the past 3 months | Not stated | Higher levels of education (B = 0.12, SE = 0.04, p = 0.002), IPV (B = 0.62, SE = 0.26, p = 0.016), and American acculturation (B = 0.44, SE = 0.16, p = 0.006) were associated with participants engaging with the intervention. Physical violence was associated with treatment engagement (χ2(1, N = 274) = 4.23, p = 0.040, OR = 2.63). | Control N = 274. Intervention arm N = 274 N = 111 (41%) did not attend any sessions. |

| Sabri & Gielen, 2019 [38] | Integrated multicomponent interventions for safety and health risks among black female survivors of violence: A systematic review | USA | a) “To describe the characteristics and effectiveness of evidence-based, integrated multicomponent intervention strategies for Black women survivors of violence”; and b) “To determine the efficacy of various integrated multicomponent interventions strategies on the following individual outcomes for survivors of violence: violence reduction, reproductive health, reduced risk of HIV, reduced stress/ stress management, and improved mental health” | Systematic review | Evaluation quantitative studies, Black women > 18 years survivors of violence, multicomponent intervention, published in English | Inventions focused on men, participants <18 years, interventions that only included one component, lacked evaluation, sample not identified and not distinguish black women as part of the sample, not conducted in the USA | Total 16 papers included in review but only one relevant paper that examined reproductive health outcomes for women experiencing IPV [43]. Individualised intervention improved pregnancy outcomes including reducing preterm births (included counselling, information about community resources, management of depression/mood and education on IPV). | Total N = 1044 (Control N = 523, intervention N = 521) [43] |

| Sabri et al., 2024 [39] | Integrated domestic violence and reproductive health interventions in India: a systematic review | India | To “identify characteristics of existing evidence based integrated domestic violence and reproductive healthcare interventions in India to identify gaps and components of interventions that demonstrate effectiveness for addressing domestic violence.” | Systematic review | (1) Quantitative or mixed-methods studies evaluating integrated DV and family planning or general reproductive health interventions, including women in prenatal, postnatal, and/or postpartum care. This included screening, prevention, and response interventions; (2) Studies using quantitative or mixed methods randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental or pre-post evaluation designs; (3) Studies that included women of ages 15 and older; (4) Studies conducted in India; (5) Studies published in peer-reviewed journals in English language from 2011–2022. | (1) Studies that did not conduct a quantitative or mixed methods evaluation of an integrated DV and family planning or general reproductive health interventions, (2) Stand-alone DV intervention studies that did not have a family planning or reproductive health component. (3) Studies that did not report findings of an evaluation trial using quantitative or mixed methods experimental, quasi-experimental or pre-post designs. (4) Qualitative studies, literature reviews and study protocols. (5) Studies that included participants under the age of 15; (4) Studies conducted outside India; (6) Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals and not published in English language; and (7) Studies published before 2011 | Total 13 papers included in review but only four relevant [44,45,46,47]. Counselling in ante-natal care environment (intervention) led to reductions in financial, emotional and physical abuse [44]. Statistically significant reduction in IPV post-counselling (intervention) [45]. Counselling/education sessions (intervention) had decrease in marital sexual coercion. Both intervention and control reported decrease in marital IPV [46,47]. | 408 women (all intervention) [44] 1136 women (numbers for intervention not stated) [45] Intervention N = 118, Control N = 102 [46,47]. |

| Uysal et al., 2023 [36] | Effects of a clinic-based reproductive empowerment intervention on proximal outcomes of contraceptive use, self-efficacy, attitudes, and awareness and use of survivor services: a cluster-controlled trial in Nairobi, Kenya | Kenya | “To evaluate the effect of a reproductive empowerment contraceptive counselling intervention (ARCHES) adapted to private clinics in Nairobi, Kenya on proximal outcomes of contraceptive use and covert use, self-efficacy, awareness and use of intimate partner violence (IPV) survivor services, and attitudes justifying reproductive coercion (RC) and IPV” | Parallel-group, prospective, non-randomised, cluster-control trial | Interested in receiving family planning services, female, aged 15–49, not pregnant or sterilised, have a male partner (history of having sex with in the last three months), staying in the area for the next six months, have a mobile phone and able to participate in an interview. | Women who took a health survey (past three months) | Women who received contraceptive counselling had higher rates of taking/using a contraceptive (86% vs. 75%, p < 0.001), and significantly greater relative increase in IPV awareness from baseline to three-month follow-up (beta 0.84, p-value 0.02, 95% CI 0.13, 1.55) and six-month follow-up (beta 0.92, p-value 0.05, 95% CI 0, 1.84). Intervention group also had decrease in attitudes justifying RC from baseline to six-month follow-up (beta −0.34, p-value 0.03, 95% CI −0.65, −0.04). | Intervention N = 328, control N = 331 (85% of total screened) Follow-up (6 months) approximately 87% intervention and 80% control |

| Author(s) and Year | Age | Sociodemographic(s) | Relationship(s) | Intervention Type | Location of Intervention | Referral to Intervention | Violence Type | How Violence was Identified | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decker et al., 2017 [42] | Lifetime experience of IPV: 55.6% aged 31–35, 45.6% aged 21–25, 34.9% aged 26–30, 12% aged 18–20 | Lifetime experience of IPV: 44% identified as White, 40% identified as Other, 31.3% identified as Black or African American | Lifetime experience of IPV: Dating one person/in a serious relationship n = 42.1%, Single/dating more than one person 30.4%, Married 30% | Discussion and/or safety card | Family planning health centre | Self-initiated contact with the research team re: project | IPV, sexual, physical, reproductive coercion | Not stated | |

| Gmelin et al., 2018 [40] | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Training leading to discussions with clients (including reproductive healthcare needs), and referral(s) to family planning clinics | ‘Project Connect’ sites (6 states in USA) | Not stated | IPV and sexual violence | Not stated | Participant details not provided. Only site leads took part in phone interviews (did not complete the training) |

| Lewis et al., 2022 [37] | 15–49 years | Not stated | Not stated | Complex healthcare interventions | Sexual health consultations | Not stated | All types of violence against women including IPV, domestic violence and abuse, family violence or non-partner sexual violence | Self | |

| Miller et al., 2011 [34] | 45.7% aged 16–20, 31.6% aged 21–24, 22.7% aged 25–29 | Identified as Hispanic 37.5%, Non-Hispanic Black 23.6%, White 22.5%, Asian/Pacific Islander/Other 11.3%, Multiracial 5.1% High school graduate 36.7%, Some college or technical school 34.5%, Some high school 18.3%, Less than high school 1.3%, Graduated from college or technical school 9.2% | In a serious relationship 47.2%, Single/Dating more than 1 person 32.2%, Married/Cohabitating 18.3%, Divorced/Separated/Widowed 2.2% | Enhanced IPV screening which focused on: “educating clients about reproductive coercion and the many forms of IPV, specifically ways in which IPV can affect sexual and reproductive health with respect to control of reproductive choices (e.g., birth control use, condom use, pregnancy and timing of pregnancy)” | 4 family planning clinics (2 intervention and 2 control) | Not stated | Birth control sabotage, Reproductive coercion, IPV (physical and/or sexual violence) | Self | |

| Miller et al., 2017 [41] | 39% aged 22–26, 33% aged 18–21, 29% aged 27–30 | 70% identified as White, 20% as African American or Black, 10% as Multiracial or other | Not stated | Staff trained to offer a trauma-informed intervention addressing intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion to all women seeking care (regardless of exposure to violence) | 11 family planning clinics—private space | All women seeking care | IPV, RC | Self | |

| Mitrani et al., 2017 [35] | Mean 37.31 (SD 8.34) | Education (years) mean 13.62 (SD 3.38) Employed n = 92 (34%) | Living with partner n = 181 (66%) | Sexual health group intervention—consisting of five, 2 h sessions delivered to small groups of women | Community sites “easily accessible to the participants” | (a) Community-based social service (English classes, child care, job development and placement, and health education) organization for Hispanics (b) An urban Florida Department of Health site (c) Flyers posted in the community (d) Study participants also referred family members and friends | IPV, emotional, sexual, physical | Self | |

| Sabri & Gielen, 2019 [38] | 18 years and over | Adult black women | Not stated | One paper related to study aims—reproductive health intervention [43] | Not stated | Not stated | IPV | Not stated | Study reported 1. Characteristics and Effectiveness of Evidence-Based, Integrated Multicomponent Intervention Studies 2. Efficacy of Integrated Multicomponent Intervention Strategies 3. interventions that were trauma-focused or included mental health as an outcome 4. interventions that included HIV risk as an outcome 5. interventions that included stress management as an outcome 6. interventions that included reproductive health issues as outcomes |

| Sabri et al., 2024 [39] | Over 15 years old, not always stated | Variable | Couples | Counselling and education | Antenatal care setting, not specified | Not specified | DV, IPV, sexual, physical, psychological | Not specified | Various counselling and education interventions—individual, household, and community wide |

| Uysal et al., 2023 [36] | Mean 26.70 (SD 6.63) | n = 160 (48.78%) secondary education level, n = 95 (28.96%) primary education level or less, n = 73 (22.26%) tertiary education level or higher n = 80 (24.39%) Food insecurity past 30 days n = 230 (70.12%) Paid work past year | n = 230 (70.12%) Married | Health provider training to integrate contraceptive counselling strategies—help women control their contraceptive use, pregnancy decisions, experiences of IPV and reproductive coercion | Six private primary-care clinics operated by a Kenya-based non-governmental organisation, Family Health Options of Kenya | Self-selected (offered a women’s health study upon clinic presentation) | IPV, RC | Not specified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

East, L.; Terry, D.; Ryan, L.; Larsen, B.; Mullens, A.B.; Brömdal, A.; Hutchinson, M.; Jedwab, R.M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091377

East L, Terry D, Ryan L, Larsen B, Mullens AB, Brömdal A, Hutchinson M, Jedwab RM. Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091377

Chicago/Turabian StyleEast, Leah, Daniel Terry, Liz Ryan, Brianna Larsen, Amy B. Mullens, Annette Brömdal, Marie Hutchinson, and Rebecca M. Jedwab. 2025. "Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091377

APA StyleEast, L., Terry, D., Ryan, L., Larsen, B., Mullens, A. B., Brömdal, A., Hutchinson, M., & Jedwab, R. M. (2025). Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091377