Trauma-Informed Understanding of Depression Among Justice-Involved Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

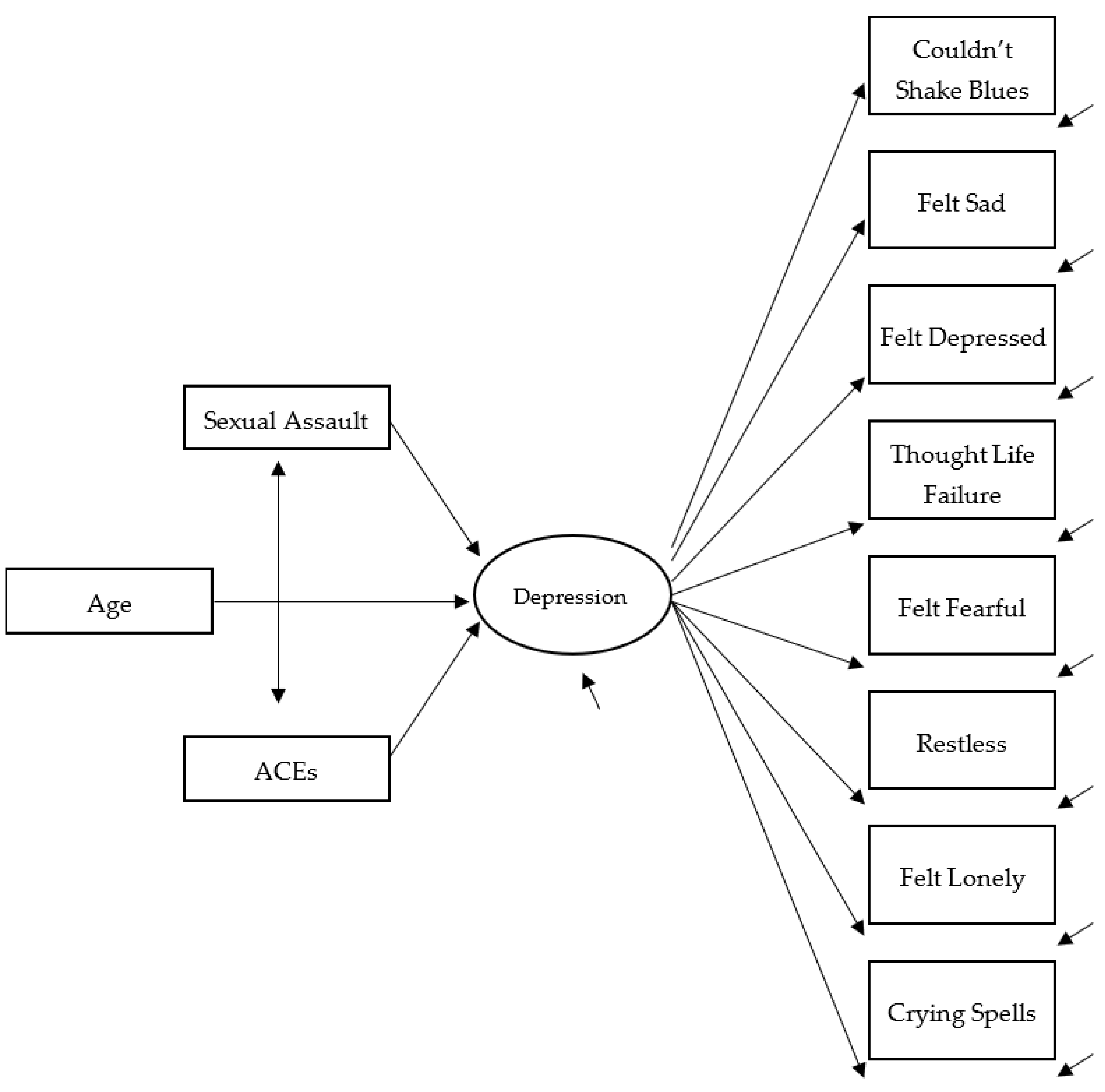

2. Estimated Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure

- To offer HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) evidence-based risk reduction information and education to youths using gender- and developmentally appropriate curricula.

- To perform analysis of youths’ provided urine specimens to test for drug use and STIs and swab testing for HIV.

- To connect youth with identified needs to appropriate community services. The service sought to follow-up with STI- and HIV-positive youth and promptly link them with appropriate treatment. Youth who screened high on an evidence-based depression inventory [68,69] were also linked with follow-up services.

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measure of Depression

3.4. Covariate Measures

3.5. Strategy of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Trauma/Stress Experiences and Depression

4.3. Model Results for Males and Females

4.4. Model Results for Non-Black and Black Youths

5. Discussion

6. Study Limitations and Their Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Implications of Our Research for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often…

- 2.

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often…

- 3.

- Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever…

- 4.

- Did you often feel that…

- 5.

- Did you often feel that…

- 6.

- Were your parents ever separated or divorced?

- 7.

- Was your mother or stepfather:

- 8.

- Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or who used street drugs?

- 9.

- Was a household member depressed or mentally ill or did a household member attempt suicide?

- 10.

- Did a household member go to prison?

References

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremmer, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Brown, J.; Smailes, E. Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Fabris, M.A. Adverse childhood experiences and body dysmorphic symptoms: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2022, 40, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión, V.G.; Haas, B.W.; Garrett, A.; Song, S.; Reiss, A.L. Reduced hippocampal activity in youth with posttraumatic stress symptoms: An fMRI study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, H.; Rubia, K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: A critical review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Zeanah, C.H. Deviations from the expectable environment in early childhood and emerging psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, C.L.; Santesso, D.L.; Dywan, J.O.; Leary, D.D.; Wade, T.J.; Segalowitz, S.J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with self-regulation and the magnitude of the error-related negativity difference. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 132, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanius, R.A.; Willaimson, P.C.; Densmore, M.; Boksman, K.; Gupta, M.A.; Neufeld, R.W.; Gati, J.S.; Menon, R.S. Neural correlates of traumatic memories in posttraumatic stress disorder: A functional MRI investigation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1920–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huffman, N.; Shi, C.H.; Cotton, A.S.; Buehler, M.; Brickman, K.R.; Wall, J.T.; Wang, X. Adverse childhood experiences associated with early post-trauma thalamus and thalamic nuclei volumes and PTSD development in adulthood. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2022, 319, 111421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, A.L.; Crouch, E. The association of adverse childhood experiences with anxiety and depression for children and youth, 8 to 17 years of age. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, S. Effects of childhood trauma on adolescent mental health. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries, Oxford, UK, 7 August 2023; Cifuentes-Faura, J., Mallen, E., Eds.; EWA Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle, B.W.; Reavley, N.J.; Li, W.; Morgan, A.; Yap, M.B.H.; Reupert, A.; Jorm, A.F. The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cheng, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, J.; Sun, W.; Xiao, W.; Liu, J.; Thai, T.T.; Al Shawi, A.F.; Zhang, D.; et al. Gender differences in the associations of adverse childhood experiences with depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 378, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, J.; Miller, K.M.; Briggs, H.E.; Kim, I.; Mowbray, O.; Orellana, R. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, major depressive episode and chronic physical health in adolescents: Moderation of race/ethnicity. Soc. Work. Public Health 2019, 34, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, C.T.; Lombardi, B.M. Examining racial differences in internalizing and externalizing diagnoses for children exposed to adverse childhood experiences. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2022, 50, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.T.; Baglivio, M.T. Adverse childhood experiences, negative emotionality, and pathways to juvenile recidivism. Crime. Delinq. 2017, 63, 1495–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvaso, C.G.; Cale, J.; Whitten, T.; Day, A.; Singh, S.; Hackett, L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Ross, S. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and trauma among young people who offend: A systematic literature review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Thiemann, R.; Deneault, A.A.; Fearon, R.M.P.; Racine, N.; Park, J.; Lunney, C.A.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Jenkins, S.; Williamson, T.; et al. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in child population samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025, 179, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zao, R.; Yao, X. Impacts of adverse and positive childhood experiences on psychological and behavioral outcomes in a sample of Chinese juvenile offenders. J. Fam. Violence 2024, accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Wolff, N. Prevalence and predictors of sexual victimization among incarcerated men and women in Spanish prisons. Crim. Justice Behav. 2016, 43, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, D.S.; Farabee, D.; Crouch, B.M. Early victimization, drug use, and criminality: A comparison of male and female prisoners. Crim. Justice Behav. 1997, 24, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, N.; Grella, C.; Burdon, W.; Prendergast, M. Childhood adverse events and current traumatic distress: A comparison of men and women drug-dependent prisoners. Crim. Justice Behav. 2007, 34, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Lee, M.A. Traumatic experiences in childhood and depressive symptoms in adulthood: The effects of social relationships. Korea J. Popul. Stud. 2016, 39, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Pyo, H.J.; Fava, M.; Mischoulon, D.; Park, M.J.; Joen, H.J. Bullying, psychological, and physical trauma during early life increase risk of major depressive disorder in adulthood: A nationwide community sample of Korean adults. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 792734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Potthoff, L.M.; Aaby, D.A.; Welty, L.J.; Dulcan, M.K.; Abram, K.M. Prevalence, comorbidity, and continuity of psychiatric disorders in a 15-year longitudinal study of youths involved in the juvenile justice system. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e205807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembo, R.; Faber, J.; Cristiano, J.; DiClemente, R.; Krupa, J.; Wareham, J.; Terminello, A. Psychometric evaluation of a brief depression measure for justice involved youth: A multi-group comparison. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2018, 27, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Depressive comorbidity in children and adolescents: Empirical, theoretical, and methodological issues. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Stoolmiller, M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999, 11, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Cohen, J.; Kasen, S.; Velez, C.N.; Hartmark, C.; Johnson, J.; Rojas, M.; Brook, J.; Streuning, E.L. An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence: I. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1993, 34, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abram, K.M.; Teplin, L.A.; McClelland, G.M.; Dulcan, M.K. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Abram, K.M.; McClelland, G.M.; Washburn, J.J.; Pikus, A.K. Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: Who receives services. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Abram, K.M.; McClelland, G.M.; Dulcan, M.K.; Mericle, A.A. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002, 59, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domalanta, D.D.; Risser, W.L.; Roberts, R.E.; Risser, J.M.H. Prevalence of depression and other psychiatric disorders among incarcerated youths. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliszka, S.R.; Sherman, J.O.; Barrow, M.V.; Irick, S. Affective disorder in juvenile offenders: A preliminary study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Elkington, K.S.; McClelland, G.M.; Abram, K.M.; Mericle, A.A.; Washburn, J.J. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005, 56, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, L.A.R.; Lebeau, R.; Colby, S.M.; Barnett, N.P.; Golembeske, C.; Monti, P.M. Motivational interviewing for incarcerated adolescents: Effects of depressive symptoms on reducing alcohol and marijuana use after release. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2011, 72, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, S.; Verhulst, F.C.; van der Ende, J. Gender differences in the development and adult outcome of co-occurring depression and delinquency in adolescence. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011, 120, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeber, R.; Pardini, D.A.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Raine, A. Do cognitive, physiological, and psychosocial risk and promotive factors predict desistance from delinquency in males? Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 867–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmorstein, N.R.; Iacono, W.G. Major depression and conduct disorder in a twin sample: Gender, functioning, and risk for future psychopathology. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Miranda, R.; Rizzo, C.J.; Justus, A.N.; Clum, G. Gender, social support, and depression in criminal justice-involved adolescents. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2011, 55, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareham, J.; Dembo, R.; Schmeidler, J.; Wolff, J.; Simon, N. Sexual trauma informed understanding of longitudinal depression among repeat juvenile offenders. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 49, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livanou, M.; Furtado, V.; Winsper, C.; Silvester, A.; Singh, S.P. Prevalence of mental disorders and symptoms among incarcerated youth: A meta-analysis of 30 studies. Int. J. Forensic Ment. Health 2019, 18, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Hammer, H.; Sedlak, A.J. Sexually Assaulted Children: National Estimates and Characteristics. National Incidence Studies of Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Throwaway Children; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=ccrc (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Snyder, H.N. Sexual Assault of Young Children as Reported to Law Enforcement: Victim, Incident, and Offender Characteristics; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/saycrle.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Weiss, K.G. “You just don’t report that kind of stuff”: Investigating teen’ ambivalence toward peer-perpetrated, unwanted sexual incidents. Violence Vict. 2013, 28, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, A.; Finkelhor, D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 99, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gover, A.R. Childhood sexual abuse, gender, and depression among incarcerated youth. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2004, 48, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koverola, C.; Pound, J.; Heger, A.; Lylte, C. Relationship of child sexual abuse to depression. Child Abus. Negl. 1993, 17, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplo, S.D.; Kerig, P.K.; Bennett, D.C.; Modrowski, C.A. The roles of emotion dysregulation and dissociation in the association between sexual abuse and self-injury among juvenile justice-involved youth. J. Trauma Dissociation 2015, 16, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Grasso, D.J.; Hawke, J.; Chapman, J.F. Poly-victimization among juvenile justice-involved youths. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Corry, J.; Slade, T.; Issakidis, C.; Swanston, H. Child sexual abuse. In Comparative Quantification of Health Risks; Ezzati, M., Lopez, D., Rodgers, A., Murray, C.J.L., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1850–1940. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241580313 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Barth, J.; Bermetz, L.; Heim, E.; Trelle, S.; Tonia, T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.A.; Shattuck, A.; Hamby, S.L. Characteristics of Crimes against Juveniles; Crimes against Children Research Center: Durham, NH, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9728770/Characteristics_of_crimes_against_juveniles (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ford, J.D. (University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT, USA); Cruise, K.R. (Fordham University, New York, NY, USA); Grasso, D.J. (University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT, USA). A Study of the Impact of Screening for Poly-Victimization in Juvenile Justice. 2017; (Unpublished Work). Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/250994.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Raj, A.; Rose, J.; Decker, M.R.; Rosengard, C.; Hebert, M.R.; Stein, M.; Clarke, J.G. Prevalence and patterns of sexual assault across the life span among incarcerated women. Violence Against Women 2008, 14, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swisher, R.R.; Shaw-Smith, U.R. Paternal incarceration and adolescent well-being: Life course contingencies and other moderators. J. Crim. Law. Criminol. 2015, 104, 929–959. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4883585/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Martin, G.; Bergen, H.A.; Richardson, A.S.; Roger, L.; Allison, S. Sexual abuse and suicidality: Gender differences in a large community sample of adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedini, K.M.; Fagan, A.A.; Gibson, C.L. The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 59, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boney-McCoy, S.; Finkelhor, D. Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal, prospective study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, J.M.; Chang, J.J.; Kotch, J.B. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.H.; Temple, J.R. Social factors associated with history of sexual assault among ethnically diverse adolescents. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Howard, D.E.; Wang, M.Q. Psychosocial correlates of U.S. adolescents who report a history of forced sexual intercourse. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 36, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muram, D.; Hostetler, B.R.; Jones, C.E.; Speck, P.M. Adolescent victims of sexual assault. J. Adolesc. Health 1995, 17, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickert, V.I.; Wiemann, C.M.; Vaughan, R.D. Rates and risk factors for sexual violence among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembo, R.; Wareham, J.; Schmeidler, J.; Wolff, J. An exploration of the effects of sexual assault victimization among justice-involved youth: Urbanity, race/ethnicity, and sex differences. Vict. Offender 2022, 17, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembo, R.; DiClemente, R.J.; Brown, R.; Faber, J.; Cristiano, J.; Terminello, A. Health coaches: An innovative and effective approach for identifying and addressing the health needs of juvenile involved youth. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J. Youth Adolesc. 1991, 20, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, L.A.; Huba, G.J.; Brown, V.B.; Reback, C.J. A short depression index for women. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, J.; Weisz, R.; Bibi, Z.; Rehman, S. Validation of the eight-item Center for Epidemiology Depression Scale (CED-S) among older adults. Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, A.M.; Kenny, R.A.; King-Kallimanis, B.L. The latent factors of depression from the short forms of the CES-D are consistent, reliable and valid in community-living older adults. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 5, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 29 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 18th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1032621937. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2017; Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Brown, J.L.; Sales, J.M.; Swartzendruber, A.L.; Eriksen, M.D.; DiClemente, R.J.; Rose, E.S. Added benefits: Reduced depressive symptom levels among African-American female adolescents participating in an HIV prevention intervention. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Santor, D.A.; Coyne, J.C. Shortening the CES-D to improve its ability to detect cases of depression. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 9, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T. Recent methods for the study of measurement invariance with many groups: Alignment and random effects. Sociol. Methods Res. 2017, 47, 637–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.T.; Kilmartin, L.; Meagher, A.; Cannon, M.; Healy, C.; Clarke, M.C. A revised and extended systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Shang, T.; Li, P. Depression in youths with early life adversity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1378807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtes, C.M.; Cederbaum, J.A. Examining the relative impact of adverse and positive childhood experiences on adolescent mental health: A strengths-based perspective. Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 157, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Male | Female | Non-Black | Black | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 219–226) | (n = 95–98) | (n = 92–95) | (n = 222–229) | |

| Male | --- | --- | 64.2% | 72.1% |

| Female | --- | --- | 35.8% | 27.9% |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 15.50 (1.31) | 15.01 (1.54) ** | 15.15 (1.52) | 15.43 (1.34) |

| ACEs total | 1.01 (0.99) | 1.44 (1.50) ** | 1.17 (1.37) | 1.13 (1.10) |

| Sexually assaulted | 0.9% | 16.8% ** | 10.9% | 3.6% * |

| Depression items: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues | 0.15 (0.56) | 0.22 (0.66) | 0.22 (0.63) | 0.15 (0.57) |

| Felt sad | 0.44 (0.86) | 0.76 (1.02) ** | 0.67 (1.02) | 0.48 (0.87) |

| Felt depressed | 0.29 (0.80) | 0.60 (1.05) ** | 0.47 (0.97) | 0.35 (0.86) |

| Thought my life a failure | 0.26 (0.73) | 0.43 (0.81) | 0.45 (0.86) | 0.26 (0.71) * |

| Felt fearful | 0.14 (0.48) | 0.33 (0.76) ** | 0.22 (0.57) | 0.19 (0.59) |

| Sleep was restless | 0.66 (1.12) | 0.67 (1.07) | 0.74 (1.17) | 0.63 (1.08) |

| Felt lonely | 0.34 (0.84) | 0.52 (1.05) | 0.50 (0.99) | 0.35 (0.88) |

| Had crying spells | 0.14 (0.54) | 0.55 (0.91) *** | 0.35 (0.73) | 0.23 (0.68) |

| Model Fit Information (Unstandardized Estimates) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of free parameters | 48 | |||

| Loglikelihood: | ||||

| H0 value | −2043.929 | |||

| H0 scaling correction factor for MLR | 1.284 | |||

| Information criteria: | ||||

| Akaike (AIC) | 4183.858 | |||

| Bayesian (BIC) | 4364.133 | |||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 4211.889 | |||

| Final class counts and proportions for the latent classes based on the estimated model | ||||

| Latent classes: | Count | Proportion | ||

| 1 (0 = Male) | 220 | 0.696 | ||

| 2 (1 = Female) | 96 | 0.304 | ||

| Model results by latent class (gender group) | ||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate/SE | p-value | |

| Latent class 1: Male | ||||

| Depression by: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues | 1.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Felt sad | 1.231 | 0.288 | 4.277 | 0.000 |

| Felt depressed | 1.402 | 0.409 | 3.427 | 0.001 |

| Thought my life a failure | 0.954 | 0.222 | 4.307 | 0.000 |

| Felt fearful | 0.847 | 0.190 | 4.457 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless | 0.584 | 0.137 | 4.259 | 0.000 |

| Felt lonely | 1.207 | 0.299 | 4.044 | 0.000 |

| Had crying spells | 0.987 | 0.253 | 3.909 | 0.000 |

| Depression on: | ||||

| ACEs | 0.654 | 0.207 | 3.158 | 0.002 |

| Sexual assault | 2.796 | 0.774 | 3.609 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.173 | 0.126 | −1.371 | 0.170 |

| ACEs with: | ||||

| Sexual assault | 0.102 | 0.109 | 0.936 | 0.349 |

| Means: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.009 | 0.067 | 15.106 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.009 | 0.007 | 1.329 | 0.184 |

| Intercepts: | ||||

| Depression | 4.866 | 3.542 | 1.374 | 0.170 |

| Thresholds: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues $1 | 6.920 | 3.067 | 2.256 | 0.024 |

| Could not shake off blues $2 | 7.417 | 3.082 | 2.407 | 0.016 |

| Could not shake off blues $3 | 9.042 | 3.187 | 2.837 | 0.005 |

| Felt sad $1 | 5.484 | 3.248 | 1.688 | 0.091 |

| Felt sad $2 | 7.012 | 3.281 | 2.137 | 0.033 |

| Felt sad $3 | 8.747 | 3.303 | 2.648 | 0.008 |

| Felt depressed $1 | 7.758 | 3.740 | 2.074 | 0.038 |

| Felt depressed $2 | 8.382 | 3.762 | 2.228 | 0.026 |

| Felt depressed $3 | 9.762 | 3.815 | 2.559 | 0.010 |

| Thought my life a failure $1 | 5.513 | 2.535 | 2.175 | 0.030 |

| Thought my life a failure $2 | 6.601 | 2.546 | 2.593 | 0.010 |

| Thought my life a failure $3 | 7.801 | 2.617 | 2.981 | 0.003 |

| Felt fearful $1 | 5.615 | 2.415 | 2.324 | 0.020 |

| Felt fearful $2 | 6.793 | 2.421 | 2.806 | 0.005 |

| Felt fearful $3 | 8.093 | 2.452 | 3.301 | 0.001 |

| Sleep was restless $1 | 2.920 | 1.605 | 1.819 | 0.069 |

| Sleep was restless $2 | 3.444 | 1.613 | 2.135 | 0.033 |

| Sleep was restless $3 | 4.187 | 1.619 | 2.585 | 0.010 |

| Felt lonely $1 | 6.765 | 3.191 | 2.120 | 0.034 |

| Felt lonely $2 | 7.276 | 3.196 | 2.277 | 0.023 |

| Felt lonely $3 | 8.316 | 3.226 | 2.578 | 0.010 |

| Had crying spells $1 | 5.935 | 2.688 | 2.208 | 0.027 |

| Had crying spells $2 | 7.021 | 2.731 | 2.571 | 0.010 |

| Had crying spells $3 | 8.343 | 2.840 | 2.938 | 0.003 |

| Variances: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.462 | 0.352 | 4.150 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.050 | 0.010 | 5.114 | 0.000 |

| Residual variances: | ||||

| Depression | 3.558 | 1.305 | 2.726 | 0.006 |

| Latent class 2: Female | ||||

| Depression by: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues | 1.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Felt sad | 1.231 | 0.288 | 4.277 | 0.000 |

| Felt depressed | 1.402 | 0.409 | 3.427 | 0.001 |

| Thought my life a failure | 0.954 | 0.222 | 4.307 | 0.000 |

| Felt fearful | 0.847 | 0.190 | 4.457 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless | 0.584 | 0.137 | 4.259 | 0.000 |

| Felt lonely | 1.207 | 0.299 | 4.044 | 0.000 |

| Had crying spells | 0.987 | 0.253 | 3.909 | 0.000 |

| Depression on: | ||||

| ACEs | 0.388 | 0.175 | 2.212 | 0.027 |

| Sexual assault | 2.287 | 0.752 | 3.042 | 0.002 |

| Age | 0.201 | 0.180 | 1.119 | 0.263 |

| ACEs with: | ||||

| Sexual assault | 0.035 | 0.018 | 1.902 | 0.057 |

| Means: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.438 | 0.152 | 9.442 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.168 | 0.038 | 4.386 | 0.000 |

| Intercepts: | ||||

| Depression | 0.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Thresholds: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues $1 | 6.920 | 3.067 | 2.256 | 0.024 |

| Could not shake off blues $2 | 7.417 | 3.082 | 2.407 | 0.016 |

| Could not shake off blues $3 | 9.042 | 3.187 | 2.837 | 0.005 |

| Felt sad $1 | 5.484 | 3.248 | 1.688 | 0.091 |

| Felt sad $2 | 7.012 | 3.281 | 2.137 | 0.033 |

| Felt sad $3 | 8.747 | 3.303 | 2.648 | 0.008 |

| Felt depressed $1 | 7.758 | 3.740 | 2.074 | 0.038 |

| Felt depressed $2 | 8.382 | 3.762 | 2.228 | 0.026 |

| Felt depressed $3 | 9.762 | 3.815 | 2.559 | 0.010 |

| Thought my life a failure $1 | 5.513 | 2.535 | 2.175 | 0.030 |

| Thought my life a failure $2 | 6.601 | 2.546 | 2.593 | 0.010 |

| Thought my life a failure $3 | 7.801 | 2.617 | 2.981 | 0.003 |

| Felt fearful $1 | 5.615 | 2.415 | 2.324 | 0.020 |

| Felt fearful $2 | 6.793 | 2.421 | 2.806 | 0.005 |

| Felt fearful $3 | 8.093 | 2.452 | 3.301 | 0.001 |

| Sleep was restless $1 | 2.920 | 1.605 | 1.819 | 0.069 |

| Sleep was restless $2 | 3.444 | 1.613 | 2.135 | 0.033 |

| Sleep was restless $3 | 4.187 | 1.619 | 2.585 | 0.010 |

| Felt lonely $1 | 6.765 | 3.191 | 2.120 | 0.034 |

| Felt lonely $2 | 7.276 | 3.196 | 2.277 | 0.023 |

| Felt lonely $3 | 8.316 | 3.226 | 2.578 | 0.010 |

| Had crying spells $1 | 5.935 | 2.688 | 2.208 | 0.027 |

| Had crying spells $2 | 7.021 | 2.731 | 2.571 | 0.010 |

| Had crying spells $3 | 8.343 | 2.840 | 2.938 | 0.003 |

| Variances: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.462 | 0.352 | 4.150 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.050 | 0.010 | 5.114 | 0.000 |

| Residual variances: | ||||

| Depression | 3.558 | 1.305 | 2.726 | 0.006 |

| Categorical latent variables: | ||||

| Means: | ||||

| G #1 (males) | 0.829 | 0.122 | 6.780 | 0.000 |

| Model Fit Information (Unstandardized Estimates) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of free parameters | 48 | |||

| Loglikelihood: | ||||

| H0 value | −2055.514 | |||

| H0 scaling correction factor for MLR | 1.267 | |||

| Information criteria: | ||||

| Akaike (AIC) | 4207.028 | |||

| Bayesian (BIC) | 4387.304 | |||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 4235.060 | |||

| Final class counts and proportions for the latent classes based on the estimated model | ||||

| Latent classes: | Count | Proportion | ||

| 1 (0 = non-Black) | 93 | 0.294 | ||

| 2 (1 = Black) | 223 | 0.706 | ||

| Model results by latent class (race group) | ||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate/SE | p-value | |

| Latent class 1: Non-Black | ||||

| Depression by: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues | 1.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Felt sad | 1.176 | 0.267 | 4.397 | 0.000 |

| Felt depressed | 1.312 | 0.380 | 3.458 | 0.001 |

| Thought my life a failure | 0.922 | 0.211 | 4.361 | 0.000 |

| Felt fearful | 0.805 | 0.181 | 4.442 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless | 0.569 | 0.130 | 4.389 | 0.000 |

| Felt lonely | 1.185 | 0.293 | 4.044 | 0.000 |

| Had crying spells | 0.938 | 0.231 | 4.057 | 0.000 |

| Depression on: | ||||

| ACEs | 0.276 | 0.244 | 1.131 | 0.258 |

| Sexual assault | 1.766 | 0.651 | 2.714 | 0.007 |

| Age | −0.030 | 0.167 | −0.181 | 0.856 |

| ACEs with: | ||||

| Sexual assault | 0.026 | 0.017 | 1.548 | 0.122 |

| Means: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.172 | 0.142 | 8.281 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.108 | 0.032 | 3.347 | 0.001 |

| Intercepts: | ||||

| Depression | 1.713 | 3.368 | 0.509 | 0.611 |

| Thresholds: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues $1 | 5.034 | 2.370 | 2.124 | 0.034 |

| Could not shake off blues $2 | 5.539 | 2.360 | 2.348 | 0.019 |

| Could not shake off blues $3 | 7.192 | 2.420 | 2.972 | 0.003 |

| Felt sad $1 | 2.964 | 2.545 | 1.164 | 0.244 |

| Felt sad $2 | 4.485 | 2.591 | 1.731 | 0.083 |

| Felt sad $3 | 6.219 | 2.645 | 2.351 | 0.019 |

| Felt depressed $1 | 4.807 | 2.796 | 1.719 | 0.086 |

| Felt depressed $2 | 5.418 | 2.815 | 1.925 | 0.054 |

| Felt depressed $3 | 6.774 | 2.895 | 2.340 | 0.019 |

| Thought my life a failure $1 | 3.591 | 1.992 | 1.803 | 0.071 |

| Thought my life a failure $2 | 4.684 | 1.997 | 2.345 | 0.019 |

| Thought my life a failure $3 | 5.889 | 2.096 | 2.810 | 0.005 |

| Felt fearful $1 | 3.869 | 1.739 | 2.225 | 0.026 |

| Felt fearful $2 | 5.042 | 1.722 | 2.928 | 0.003 |

| Felt fearful $3 | 6.339 | 1.732 | 3.660 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless $1 | 1.746 | 1.225 | 1.425 | 0.154 |

| Sleep was restless $2 | 2.274 | 1.226 | 1.855 | 0.064 |

| Sleep was restless $3 | 3.022 | 1.244 | 2.429 | 0.015 |

| Felt lonely $1 | 4.394 | 2.503 | 1.756 | 0.079 |

| Felt lonely $2 | 4.914 | 2.510 | 1.958 | 0.050 |

| Felt lonely $3 | 5.970 | 2.542 | 2.348 | 0.019 |

| Had crying spells $1 | 3.894 | 2.542 | 2.348 | 0.019 |

| Had crying spells $2 | 4.974 | 2.076 | 2.396 | 0.017 |

| Had crying spells $3 | 6.293 | 2.173 | 2.895 | 0.004 |

| Variances: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.425 | 0.230 | 6.196 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.053 | 0.011 | 4.722 | 0.000 |

| Residual variances: | ||||

| Depression | 3.926 | 1.425 | 2.755 | 0.006 |

| Latent class 2: Black | ||||

| Depression by: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues | 1.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Felt sad | 1.176 | 0.267 | 4.397 | 0.000 |

| Felt depressed | 1.312 | 0.380 | 3.458 | 0.001 |

| Thought my life a failure | 0.922 | 0.211 | 4.361 | 0.000 |

| Felt fearful | 0.805 | 0.181 | 4.442 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless | 0.569 | 0.130 | 4.389 | 0.000 |

| Felt lonely | 1.185 | 0.293 | 4.044 | 0.000 |

| Had crying spells | 0.935 | 0.231 | 4.057 | 0.000 |

| Depression on: | ||||

| ACEs | 0.704 | 0.205 | 3.438 | 0.001 |

| Sexual assault | 3.053 | 1.049 | 2.910 | 0.004 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.132 | 0.033 | 0.973 |

| ACEs with: | ||||

| Sexual assault | 0.083 | 0.042 | 1.976 | 0.048 |

| Means: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.126 | 0.073 | 15.318 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.036 | 0.013 | 2.880 | 0.004 |

| Intercepts: | ||||

| Depression | 0.000 | 0.000 | --- | --- |

| Thresholds: | ||||

| Could not shake off blues $1 | 5.034 | 2.370 | 2.124 | 0.034 |

| Could not shake off blues $2 | 5.539 | 2.360 | 2.348 | 0.019 |

| Could not shake off blues $3 | 7.192 | 2.420 | 2.972 | 0.003 |

| Felt sad $1 | 2.964 | 2.545 | 1.164 | 0.244 |

| Felt sad $2 | 4.485 | 2.591 | 1.731 | 0.083 |

| Felt sad $3 | 6.219 | 2.645 | 2.351 | 0.019 |

| Felt depressed $1 | 4.807 | 2.796 | 1.719 | 0.086 |

| Felt depressed $2 | 5.418 | 2.815 | 1.925 | 0.054 |

| Felt depressed $3 | 6.774 | 2.895 | 2.340 | 0.019 |

| Thought my life a failure $1 | 3.591 | 1.992 | 1.803 | 0.071 |

| Thought my life a failure $2 | 4.684 | 1.997 | 2.345 | 0.019 |

| Thought my life a failure $3 | 5.889 | 2.096 | 2.810 | 0.005 |

| Felt fearful $1 | 3.869 | 1.739 | 2.225 | 0.026 |

| Felt fearful $2 | 5.042 | 1.722 | 2.928 | 0.003 |

| Felt fearful $3 | 6.339 | 1.732 | 3.660 | 0.000 |

| Sleep was restless $1 | 1.746 | 1.225 | 1.425 | 0.154 |

| Sleep was restless $2 | 2.274 | 1.226 | 1.855 | 0.064 |

| Sleep was restless $3 | 3.022 | 1.244 | 2.429 | 0.015 |

| Felt lonely $1 | 4.394 | 2.503 | 1.756 | 0.079 |

| Felt lonely $2 | 4.914 | 2.510 | 1.958 | 0.050 |

| Felt lonely $3 | 5.970 | 2.542 | 2.348 | 0.019 |

| Had crying spells $1 | 3.894 | 2.056 | 1.894 | 0.058 |

| Had crying spells $2 | 4.974 | 2.076 | 2.396 | 0.017 |

| Had crying spells $3 | 6.293 | 2.173 | 2.895 | 0.004 |

| Variances: | ||||

| ACEs | 1.425 | 0.230 | 6.196 | 0.000 |

| Sexual assault | 0.053 | 0.011 | 4.722 | 0.000 |

| Residual variances: | ||||

| Depression | 3.926 | 1.425 | 2.755 | 0.006 |

| Categorical latent variables: | ||||

| Means: | ||||

| G #1 (non-Black) | −0.875 | 0.123 | −7.085 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dembo, R.; Swezey, A.; Herrera, R.; Melendez, L.; Geiger, C.; Bittrich, K.; Wareham, J.; Schmeidler, J. Trauma-Informed Understanding of Depression Among Justice-Involved Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091371

Dembo R, Swezey A, Herrera R, Melendez L, Geiger C, Bittrich K, Wareham J, Schmeidler J. Trauma-Informed Understanding of Depression Among Justice-Involved Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091371

Chicago/Turabian StyleDembo, Richard, Alexis Swezey, Rachel Herrera, Luz Melendez, Camille Geiger, Kerry Bittrich, Jennifer Wareham, and James Schmeidler. 2025. "Trauma-Informed Understanding of Depression Among Justice-Involved Youth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091371

APA StyleDembo, R., Swezey, A., Herrera, R., Melendez, L., Geiger, C., Bittrich, K., Wareham, J., & Schmeidler, J. (2025). Trauma-Informed Understanding of Depression Among Justice-Involved Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091371