Long COVID Symptom Management Through Self-Care and Nonprescription Treatment Options: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. What Is Known About Long COVID?

3.1. Definition

3.2. Prevalence

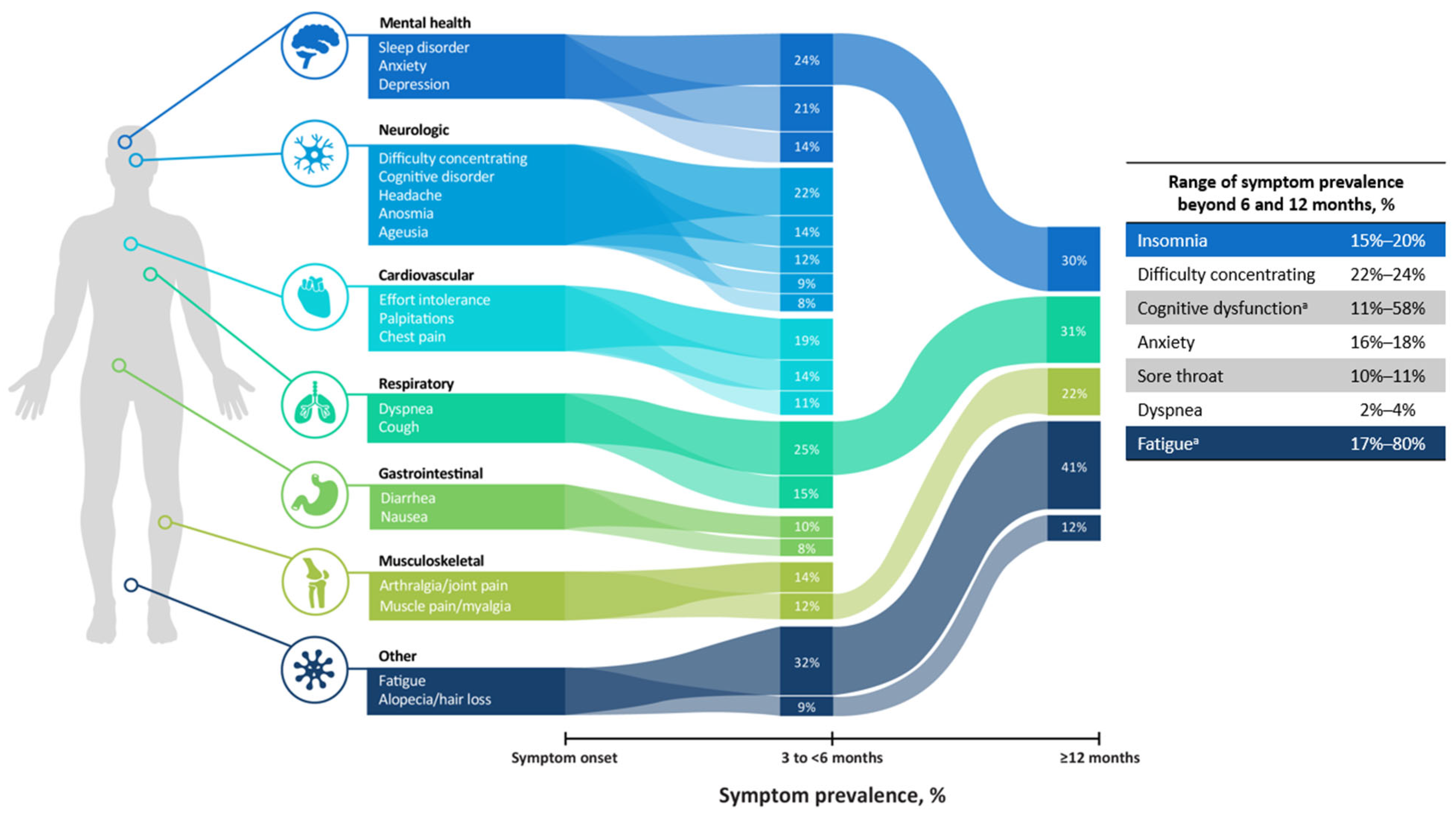

3.3. Symptoms of Long COVID

4. Recommendations for Nonprescription Management of Select Long COVID Symptoms

4.1. Fatigue

4.2. Neurologic

4.2.1. Cognitive Impairment

4.2.2. Anosmia

4.2.3. Anxiety, Depression, Psychiatric Illness

4.3. Pain

4.3.1. Nonspecific Pain

4.3.2. Headache

4.3.3. Flu-like Symptoms

4.4. Respiratory

4.4.1. Cough

4.4.2. Dyspnea

4.5. Gastrointestinal

5. Ongoing Research

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPM&R | American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation |

| CCS | Chronic COVID Syndrome |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CoQ10 | Coenzyme Q10 |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HCPs | Health care practitioners |

| ME | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PASC | Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| PCC | Post-COVID condition |

| PESE | Postexertional symptom exacerbation |

| PPIs | Proton pump inhibitors |

| RECOVER | Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| VA | United States Department of Veterans Affairs |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Sisó-Almirall, A.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Conangla Ferrín, L.; Kostov, B.; Moragas Moreno, A.; Mestres, J.; Sellarès, J.; Galindo, G.; Morera, R.; Basora, J.; et al. Long COVID-19: Proposed Primary Care Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Disease Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Long COVID: An Epidemic within the Pandemic. COVID 2023, 3, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Action Plan on Long COVID; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/lab-leak-true-origins-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Koc, H.C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G. Long COVID and Its Management. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4768–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarialiabad, H.; Taghrir, M.H.; Abdollahi, A.; Ghahramani, N.; Kumar, M.; Paydar, S.; Razani, B.; Mwangi, J.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Malekmakan, L.; et al. Long COVID, a Comprehensive Systematic Scoping Review. Infection 2021, 49, 1163–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Cases|WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Baig, A.M. Deleterious Outcomes in Long-Hauler COVID-19: The Effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the CNS in Chronic COVID Syndrome. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 4017–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaweethai, T.; Jolley, S.E.; Karlson, E.W.; Levitan, E.B.; Levy, B.; McComsey, G.A.; McCorkell, L.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Parthasarathy, S.; Singh, U.; et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Clinical Case Definition for Post COVID-19 Condition in Children and Adolescents by Expert Consensus. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-CA-Clinical-case-definition-2023-1 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Clinical Management of COVID-19: Living Guideline, 18 August 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2023.2 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. A long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27768/a-long-covid-definition-a-chronic-systemic-disease-state-with (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Long COVID. Available online: http://cdc.gov/covid/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html#:~:text=Long%20COVID%2C%20also%20known%20as,affects%20one%20or%20more%20organ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-COVID Conditions: Information for Healthcare Providers. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Perlis, R.H.; Santillana, M.; Ognyanova, K.; Safarpour, A.; Lunz Trujillo, K.; Simonson, M.D.; Green, J.; Quintana, A.; Druckman, J.; Baum, M.A.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Long COVID Symptoms Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2238804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahoney, L.L.; Routen, A.; Gillies, C.; Ekezie, W.; Welford, A.; Zhang, A.; Karamchandani, U.; Simms-Williams, N.; Cassambai, S.; Ardavani, A.; et al. The Prevalence and Long-Term Health Effects of Long Covid among Hospitalised and Non-Hospitalised Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101762, Erratum in eClinicalMedicine, 2023, 59, 101959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 Long-Term Effects of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, 2022–2023. Long COVID. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major Findings, Mechanisms and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 Condition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkodaymi, M.S.; Omrani, O.A.; Ashraf, N.; Shaar, B.A.; Almamlouk, R.; Riaz, M.; Obeidat, M.; Obeidat, Y.; Gerberi, D.; Taha, R.M.; et al. Prevalence of Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome Symptoms at Different Follow-up Periods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Bae, S.; Chang, H.-H.; Kim, S.-W. Long COVID Prevalence and Impact on Quality of Life 2 Years after Acute COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agergaard, J.; Gunst, J.D.; Schiøttz-Christensen, B.; Østergaard, L.; Wejse, C. Long-Term Prognosis at 1.5 Years after Infection with Wild-Type Strain of SARS-CoV-2 and Alpha, Delta, as Well as Omicron Variants. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 137, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katie, B. New Data Shows Long Covid is Keeping As Many as 4 Million People Out of Work. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/new-data-shows-long-covid-is-keeping-as-many-as-4-million-people-out-of-work/#:~:text=Around%2016%20million%20working%2Dage,as%20high%20as%20%24230%20billion (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Mirin, A.A. A Preliminary Estimate of the Economic Impact of Long COVID in the United States. Fatigue: Biomed. Health Behav. 2022, 10, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D. The Economic Cost of Long COVID: An Update. Available online: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/mrcbg/programs/growthpolicy/economic-cost-long-covid-update-david-cutler (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Brown, K.; Yahyouche, A.; Haroon, S.; Camaradou, J.; Turner, G. Long COVID and Self-Management. Lancet 2022, 399, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolich, J.Ž.; Rosen, C.J. Toward Comprehensive Care for Long Covid. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2113–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Treatment Clinical Care for Outpatients. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/hcp/clinical-care/outpatient-treatment.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Gulick, R.M.; Pau, A.K.; Daar, E.; Evans, L.; Gandhi, R.T.; Tebas, P.; Ridzon, R.; Masur, H.; Lane, H.C.; NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel; et al. National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel: Perspectives and Lessons Learned. Ann Intern Med 2024, 177, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.; Boivin, G.; Cowling, B.J.; Pavia, A.; Selvarangan, R. Treatment of COVID-19 Symptoms with over the Counter (OTC) Medicines Used for Treatment of Common Cold and Flu. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2023, 19, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health System Approach to Long COVID. Available online: https://www.publichealth.va.gov/n-coronavirus/docs/Whole-Health-System-Approach-to-Long-COVID_080122_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Support for Rehabilitation: Self-Management after COVID-19 Related Illness. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/support-for-rehabilitation-self-management-after-covid-19-related-illness (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Greenhalgh, T.; Knight, M.; A’Court, C.; Buxton, M.; Husain, L. Management of Post-Acute Covid-19 in Primary Care. BMJ 2020, 370, m3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, C. Long COVID and ME/CFS; The ME Association: Buckinghamshire, UK, 2021. Available online: https://meassociation.org.uk/2021/05/long-covid-me-cfs-information-management-by-dr-charles-shepherd/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Herrera, J.E.; Niehaus, W.N.; Whiteson, J.; Azola, A.; Baratta, J.M.; Fleming, T.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Naqvi, H.; Sampsel, S.; Silver, J.K.; et al. Multidisciplinary Collaborative Consensus Guidance Statement on the Assessment and Treatment of Fatigue in Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC) Patients. Pm R 2021, 13, 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.; Hall, K.H.; Tate, W. Role of Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress and the Response to Antioxidants in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Possible Approach to SARS-CoV-2 “Long-Haulers”? Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2021, 7, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, L.A.; Morrow, A.; Chen, Y.; Curtis, D.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Desai, M.; Fleming, T.K.; Giglia, T.M.; Hall, T.A.; Henning, E.; et al. Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Consensus Guidance Statement on the Assessment and Treatment of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC) in Children and Adolescents. PM R 2022, 14, 1241–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.; Keenan, L.; Dunne, E. Aromatherapy Blend of Thyme, Orange, Clove Bud, and Frankincense Boosts Energy Levels in Post-COVID-19 Female Patients: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 67, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.S.; Ambrose, A.F.; Didehbani, N.; Fleming, T.K.; Glashan, L.; Longo, M.; Merlino, A.; Ng, R.; Nora, G.J.; Rolin, S.; et al. Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Consensus Guidance Statement on the Assessment and Treatment of Cognitive Symptoms in Patients with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC). PM R 2022, 14, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Cholevas, C.; Polyzoidis, K.; Politis, A. Long-COVID Syndrome-Associated Brain Fog and Chemofog: Luteolin to the Rescue. Biofactors 2021, 47, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maley, J.H.; Alba, G.A.; Barry, J.T.; Bartels, M.N.; Fleming, T.K.; Oleson, C.V.; Rydberg, L.; Sampsel, S.; Silver, J.K.; Sipes, S.; et al. Multi-Disciplinary Collaborative Consensus Guidance Statement on the Assessment and Treatment of Breathing Discomfort and Respiratory Sequelae in Patients with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC). PM R 2022, 14, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.E.; Abramoff, B. COVID-19: Management of Adults with Persistent Symptoms Following Acute Illness (“Long COVID”). Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-adults-with-persistent-symptoms-following-acute-illness-long-covid (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Rai, D.K.; Sharma, P.; Karmakar, S.; Thakur, S.; Ameet, H.; Yadav, R.; Gupta, V.B. Approach to Post COVID-19 Persistent Cough: A Narrative Review. Lung India 2023, 40, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, N.; Grill, M.F.; Singh, R.B.H. Post-COVID Headache: A Literature Review. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker-Davies, R.M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Senaratne, K.P.P.; Baker, P.; Cranley, M.; Dharm-Datta, S.; Ellis, H.; Goodall, D.; Gough, M.; Lewis, S.; et al. The Stanford Hall Consensus Statement for Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawey, B.; Yang, J.; Bauer, B.; Song, J.; Wang, X.J. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Long COVID: A Systematic Review. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2023, 14, 20406223231190548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long Covid-Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosato, M.; Ciciarello, F.; Zazzara, M.B.; Pais, C.; Savera, G.; Picca, A.; Galluzzo, V.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E.; et al. Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements for Older Adults with Long COVID-19. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 38, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Sillett, R.; Zhu, L.; Mendel, J.; Camplisson, I.; Dercon, Q.; Harrison, P.J. Neurological and Psychiatric Risk Trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 Infection: An Analysis of 2-Year Retrospective Cohort Studies Including 1,284,437 Patients. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Lansang, N.M.; Gopaul, U.; Ogawa, E.F.; Heyn, P.C.; Santos, F.H.; Sood, P.; Zanwar, P.P.; Schwertfeger, J.; Faieta, J. What Do I Need to Know About Long-Covid-Related Fatigue, Brain Fog, and Mental Health Changes? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, P.D.; Camaioni, A.; Marra, P.; Salzano, G.; Carriere, G.; Ricciardi, L.; Pucci, R.; Montemurro, N.; Brenner, M.J.; Stadio, A.D. Effect of Ultra-Micronized Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin on Olfaction and Memory in Patients with Long COVID: Results of a Longitudinal Study. Cells 2022, 11, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukahara, T.; Brann, D.H.; Datta, S.R. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-Associated Anosmia. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butowt, R.; Bilinska, K.; von Bartheld, C.S. Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19: New Insights into the Underlying Mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, J.B.; Gallagher, L.; Joseph, P.V.; Reed, D.; Gudis, D.A.; Overdevest, J.B. Qualitative Olfactory Dysfunction and COVID-19: An Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations for the Clinician. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2023, 37, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Deng, J.; Lu, F.; Xiao, J. Virtual Reality Enhanced Mindfulness and Yoga Intervention for Postpartum Depression and Anxiety in the Post COVID Era. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePace, N.L.; Colombo, J. Long Covid Syndrome: A Multi Organ Disorder. Cardiol. Open Access 2022, 7, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzhner, O.; Berla, E.; Har-Even, M.; Ratmansky, M.; Goor-Aryeh, I. Consistency of Inconsistency in Long-COVID-19 Pain Symptoms Persistency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 120–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, V.; Zazzara, M.B.; Ciciarello, F.; Tosato, M.; Bizzarro, A.; Paglionico, A.; Varriano, V.; Gremese, E.; Calvani, R.; Landi, F.; et al. Use of First-Line Oral Analgesics during and after COVID-19: Results from a Survey on a Sample of Italian 696 COVID-19 Survivors with Post-Acute Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visalakshy, J.; George, T.; Easwar, S.V. Joint Manifestations Following COVID-19 Infection- A Case Series of Six Patients. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2022, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.R.; Simms-Williams, N.; Bashir, N.Z.; Camaradou, J.; Heining, D.; Turner, G.M.; Rivera, S.C.; Hotham, R.; Minhas, S.; et al. Non-Pharmacological Therapies for Post-Viral Syndromes, Including Long COVID: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tana, C.; Bentivegna, E.; Cho, S.-J.; Harriott, A.M.; García-Azorín, D.; Labastida-Ramirez, A.; Ornello, R.; Raffaelli, B.; Beltrán, E.R.; Ruscheweyh, R.; et al. Long COVID Headache. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutant, E.-M.; Meyrignac, O.; Beurnier, A.; Jaïs, X.; Pham, T.; Morin, L.; Boucly, A.; Bulifon, S.; Figueiredo, S.; Harrois, A.; et al. Respiratory Symptoms and Radiological Findings in Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 8, 00479–02021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goërtz, Y.M.J.; Van Herck, M.; Delbressine, J.M.; Vaes, A.W.; Meys, R.; Machado, F.V.C.; Houben-Wilke, S.; Burtin, C.; Posthuma, R.; Franssen, F.M.E.; et al. Persistent Symptoms 3 Months after a SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The Post-COVID-19 Syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00542–02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.Y.M.; Chan, A.Y.L.; Chan, E.W.; Chan, V.K.Y.; Chui, C.S.L.; Cowling, B.J.; Gao, L.; Ge, M.Q.; Hung, I.F.N.; Ip, M.S.M.; et al. Short- and Potential Long-Term Adverse Health Outcomes of COVID-19: A Rapid Review. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfì, A.; Bernabei, R.; Landi, F. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.S.; Carlsten, C.; Johnston, J.C.; Shah, A.S.; Wong, A.W.; Ryerson, C.J. Post-COVID Dyspnea: Prevalence, Predictors, and Outcomes in a Longitudinal, Prospective Cohort. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Pick, A.; Lardner, R.; Masey, V.; Smith, N.; Greenhalgh, T. Breathing Difficulties after Covid-19: A Guide for Primary Care. BMJ 2023, 381, e074937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackett, J.W.; Wainberg, M.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Freedberg, D.E. Potential Long Coronavirus Disease 2019 Gastrointestinal Symptoms 6 Months After Coronavirus Infection Are Associated with Mental Health Symptoms. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 648–650.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, R.; De Rose, C.; Cardinali, S.; Valentini, P.; Buonsenso, D. Lactoferrin as Possible Treatment for Chronic Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children with Long COVID: Case Series and Literature Review. Children 2022, 9, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, Complications and Management of Long COVID: A Review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroon, S.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.E.; Subramanian, A.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Davies, E.H.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Turner, G.; Chandan, J.S.; et al. Therapies for Long COVID in Non-Hospitalised Individuals: From Symptoms, Patient-Reported Outcomes and Immunology to Targeted Therapies (The TLC Study). BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceban, F.; Kulzhabayeva, D.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Gill, H.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Lui, L.M.W.; Cao, B.; Mansur, R.B.; Ho, R.C.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination for the Prevention and Treatment of Long COVID: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 111, 211–229, Erratum in: Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 111, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariati, M.; Gill, K.L.; Peddle, M.; Cao, Y.; Xie, F.; Han, X.; Lei, N.; Prowse, R.; Shan, D.; Fang, L.; et al. Long COVID and Associated Factors Among Chinese Residents Aged 16 Years and Older in Canada: A Cross-Sectional Online Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Larson, J.L.; Veliz, P.T.; Kitto, K.; Smith, S. Profiles of Long COVID Symptoms and Self-Efficacy for Self-Management: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2025, 84, 151968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptom | Recommendation | Type of Support/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| General signs and symptoms | ||

| Fatigue | Convalescence | ME Association [37] |

| Energy conservation and pacing | WHO [10] ME Association | |

| AAPM&R [38] | ||

| Dietary supplements, vitamins (B12, C, D), fish oil (DHA/EPA) 1000 mg | VA [34] ME Association [37] | |

| AAPM&R [38] | ||

| Davis et al. [20] | ||

| CoQ10 | AAPM&R [38] | |

| Wood et al. [39] Davis et al. [20] | ||

| Lifestyle modification, healthy diet, hydration, sleep | AAPM&R [38] AAPM&R [40] | |

| Aromatherapy (blend of essential oils from thyme, orange peel, clove bud, and frankincense) | Hawkins et al. [41] | |

| Fever | Paracetamol, NSAIDs | Greenhalgh et al. [36] |

| Neurologic | ||

| Memory, concentration, attention, language, sleep issues | Self-management, cognitive exercises, attention and memory strategies, supportive management, diaphragmatic breathing | WHO [10] VA [34] |

| AAPM&R [42] | ||

| Cognitive pacing | Davis et al. [20] | |

| Word-finding and comprehension strategies | AAPM&R [42] | |

| Luteolin | Theoharides et al. [43] | |

| Symptom monitoring | Greenhalgh et al. [36] | |

| Anosmia | Olfactory training | VA [34] WHO [10] |

| Depression/anxiety | Vitamins, electrolyte supplements | CDC [14] |

| Fish oil | VA [34] | |

| Psychological support | WHO [10] VA [34] NICE [12] | |

| Greenhalgh et al. [36] | ||

| Mindfulness-based approaches (stress reduction, meditation) | WHO [10] | |

| Peer support groups | WHO [10] VA [34] | |

| Greenhalgh et al. [36] | ||

| Exercise training | WHO [10] VA [34] | |

| Self-care (yoga, tai chi) | WHO [10] VA [34] | |

| Greenhalgh et al. [36] | ||

| Respiratory | ||

| Shortness of breath | Self-management, breathing exercises, exercise training, and pacing | WHO [10] CDC [14] VA [34] |

| AAPM&R [44] | ||

| Mikkelsen and Abramoff [45]; Akbarialiabad et al. [5] | ||

| Pulmonary rehabilitation exercises | VA [34] | |

| AAPM&R [44] | ||

| Posture improvement | AAPM&R [44] | |

| Heart-healthy diet | VA [34] | |

| Persistent cough | Self-directed breathing exercises and airway clearance techniques | VA [34] |

| AAPM&R [44] | ||

| Greenhalgh et al. [36] | ||

| Cough suppressants (e.g., benzonatate, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, gabapentin, amitriptyline, lidocaine, beta-agonists, leukotriene antagonists) | Mikkelsen and Abramoff [45]; Rai et al. [46] | |

| Excess sputum management (expectorants, hydration, airway clearance techniques) | VA [34] | |

| AAPM&R [44] | ||

| Pain | ||

| Headache | Nonprescription analgesics such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) | VA [34] |

| AAPM&R [40] | ||

| Chhabra et al. [47] | ||

| Electrolyte supplements, melatonin | AAPM&R [40] | |

| Hydration | VA [34] | |

| Maintenance of glucose levels | VA [34] | |

| Lifestyle management (regular sleep, meals, hydration, and exercise with stress management) | VA [34] | |

| AAPM&R [40] | ||

| Supportive management and symptom monitoring | Greenhalgh et al. [36] | |

| Muscle/joint pain | Pain education and self-management | WHO [10] |

| Anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) and analgesics (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, trolamine salicylate, diclofenac) | WHO [10] | |

| AAPM&R [40] | ||

| Chest pain | NSAIDS (ibuprofen) | VA [34] |

| Mikkelsen and Abramoff [45] | ||

| Sore throat | Paracetamol, aspirin, ibuprofen | Eccles et al. [33] |

| Other | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Probiotics | Davis et al. [20] |

| Dietary supplementation | Stanford Hall (United Kingdom) Consensus Statement for Post-COVID Rehabilitation [48] | |

| Herbal medicine with/without acupuncture | Gawey et al. [49] | |

| Chronic inflammation | NSAIDs, CoQ10, and antioxidants | Akbarialiabad et al. [5] |

| NCT | Intervention | Study Size | End Date/Anticipated End Date | Sponsor | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04810065 | Twice-weekly singing and breathing retraining intervention conducted over 10 weeks | 30 patients with lung issues due to COVID-19 including breathing difficulties, shortness of breath, and/or reduced exercise tolerance | 1 September 2021 | University of Limerick | 12-week COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) |

| NCT04841759 | Physical exercise–based rehabilitation program | 46 healthcare workers with and without post–COVID-19 fatigue | 22 December 2021 | Medical University of Vienna | Change of maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) from baseline to 4 weeks and 8 weeks |

| NCT04809974 | Niagen (nicotinamide riboside) | 70 participants with long COVID | 23 February 2024 | Massachusetts General Hospital | Executive functioning and memory composite scores at baseline vs. 12 and 22 weeks |

| NCT04813718 | Omni-Biotic Pro Vi 5 (probiotic) | 20 participants with long COVID | 7 December 2024 | Medical University of Graz | Microbiome composition, multiple gut signaling biomarkers, and lung function tests |

| NCT05121766 | Omega-3 (EPA + DHA) | 100 healthcare workers with long COVID | 21 April 2023 | Hackensack Meridian Health | Feasibility study: levels of compliance, interest, and completion |

| NCT04960215 | Coenzyme Q10 | 121 participants with long COVID | 10 February 2022 | Aarhus University Hospital | Self-reported symptoms and symptom scores |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kachroo, P.; Boivin, G.; Cowling, B.J.; Shannon, W.; Mallefet, P.; Kalita, P.; Georgescu, A.M. Long COVID Symptom Management Through Self-Care and Nonprescription Treatment Options: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091362

Kachroo P, Boivin G, Cowling BJ, Shannon W, Mallefet P, Kalita P, Georgescu AM. Long COVID Symptom Management Through Self-Care and Nonprescription Treatment Options: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091362

Chicago/Turabian StyleKachroo, Preeti, Guy Boivin, Benjamin J. Cowling, Will Shannon, Pascal Mallefet, Pranab Kalita, and Alexandru M. Georgescu. 2025. "Long COVID Symptom Management Through Self-Care and Nonprescription Treatment Options: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091362

APA StyleKachroo, P., Boivin, G., Cowling, B. J., Shannon, W., Mallefet, P., Kalita, P., & Georgescu, A. M. (2025). Long COVID Symptom Management Through Self-Care and Nonprescription Treatment Options: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091362