2.3. Results

A total of 65 participants were screened for eligibility, and of those, 28 qualified for this study. Most common reasons for ineligibility included not meeting criteria for elevated depression or PTSD symptoms (95% of total ineligible,

n = 35), not self-reporting adherence challenges (84% of total ineligible,

n = 31), and no delayed PrEP pickup (78% of total ineligible,

n = 29); these reasons were not mutually exclusive, with many individuals meeting multiple criteria for exclusion. The final sample consisted of 28 PPPs, all of whom identified as women and had an average age of 28.9 years (SD = 7.4). At the time of the interview, pregnant participants (

n = 10) were, on average, 25.9 weeks pregnant (SD = 8.0), while postpartum participants (

n = 18) were, on average, 9.4 weeks post-delivery (SD = 11.2). Per medical chart review, 16 participants had recently been initiated on PrEP (<1 month) and 8 had PrEP adherence challenges (>2 weeks late to pick up PrEP refill). Of the 28 participants, 23 participants had self-reported PrEP adherence challenges, 7 of whom were also late to pick up their PrEP refills. Of the 28 participants, 16 (57.1%) had elevated depression and PTSD symptoms, 11 (39.3%) had elevated depression symptoms alone, and 1 (3.6%) had elevated PTSD symptoms alone. See

Table 1 for full demographic details. The six providers who completed an interview were all professional nurses, averaged 8.3 years (11.9) working in antenatal care, and all endorsed asking patients about their mental health during clinic visits. See

Table 2 for providers’ full details.

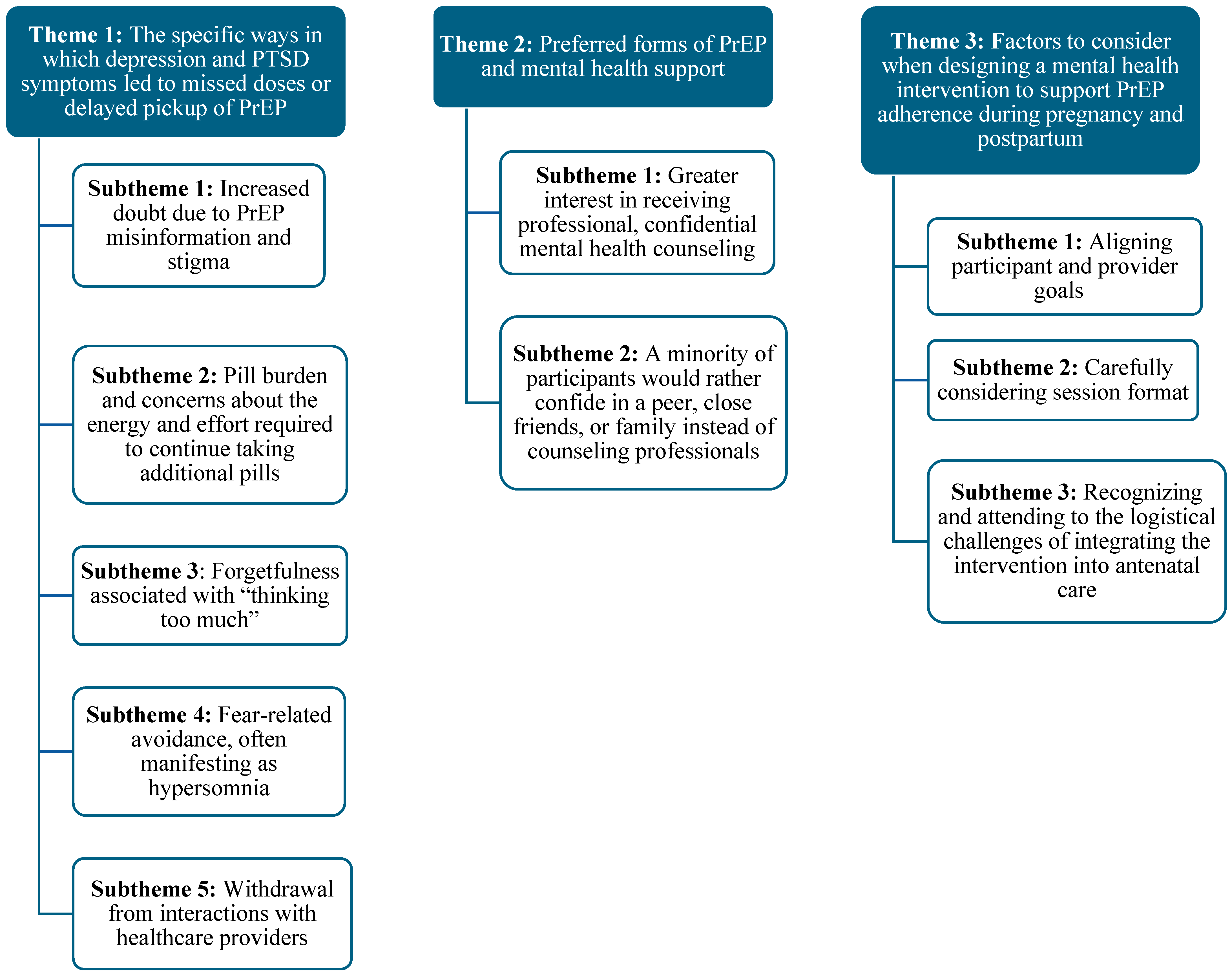

Our qualitative analyses revealed several psychological pathways to compromised PrEP use. Theme 1 articulates the specific ways in which depression and PTSD symptoms (e.g., sadness, anhedonia, shame, anxiety or stress, difficulty concentrating, avoidance, and withdrawal) led to missed doses or delayed pickup of PrEP at the clinic. Symptoms of both disorders contributed to PrEP use challenges via (1) increased doubt of PrEP efficacy, stemming from PrEP misinformation and stigma; (2) a strong sense of pill burden and concerns about the energy and effort required to continue taking pills; (3) forgetfulness associated with “thinking too much”, (4) fear-related avoidance manifesting as hypersomnia; and (5) withdrawal from interactions with healthcare providers. Theme 2 narrows in on preferred forms of PrEP support, with subthemes indicating (1) greater interest in receiving professional, confidential mental health counseling to support PrEP adherence and improve emotional well-being; (2) with a minority of participants preferring to confide in a peer, close friends, or family instead of counseling professionals. Finally, Theme 3 explicates the factors that are critical to consider when designing a mental health intervention to support PrEP adherence during pregnancy and postpartum, including (1) shared recognition of mental health as a foundation for PrEP adherence; (2) selecting an appropriate session format (group based vs. individual); and (3) addressing the logistical challenges of clinical integration. Themes and subthemes are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Depression and PTSD symptoms leading to PrEP non-adherence, subtheme 1: increased doubt due to PrEP misinformation and stigma. Among participants experiencing symptoms of depression and/or PTSD, a prominent mechanism through which these mental health challenges impacted PrEP adherence was increased doubt about PrEP efficacy, fueled by misinformation and HIV-related stigma. Sadness, hopelessness, and cognitive symptoms such as rumination and indecision often intensified uncertainty about whether PrEP would be effective in preventing HIV, particularly during pregnancy. One participant shared, “When I was feeling sad, I would start doubting and questioning if PrEP would really prevent me and my baby from getting HIV. I would start thinking about all the rumors people spread about PrEP” (postpartum, age 22). While this participant ultimately continued taking PrEP to protect her baby, others described how emotional distress and misinformation eroded their motivation.

Stigma also played a critical role. Several participants described feeling judged when swallowing pills in the presence of others due to the assumption that they were taking antiretroviral therapy for HIV treatment rather than PrEP for prevention. One participant explained, “Some people assume that it’s ARVs and don’t know what the pills are for so to avoid drama, I don’t take it in front of people besides my partner” (postpartum, age 23). A provider echoed this concern, noting that stigma and misconceptions could lead patients to hide their medication or skip doses to avoid conflict or mistrust in relationships: “People assuming that the patient is hiding their HIV status by saying they’re taking PrEP instead of ARVs. So, they would hide their pills because of the stigma. Sometimes the partner would tell them to not take PrEP or else there’s no trust between them” (provider, age 62). These accounts highlight how anticipated and experienced stigma, likely amplified by mental health symptoms, can undermine adherence.

Depression and PTSD symptoms leading to PrEP non-adherence, subtheme 2: strong sense of pill burden and concerns about the energy and effort required to continue taking additional pills. For many participants, the act of consistently taking PrEP felt physically and emotionally burdensome. A core theme across interviews was a sense of pill fatigue, that is, feeling overwhelmed by the effort required to maintain daily pill-taking amidst already diminished mental and emotional resources. For example, one participant explained, “I will see once I have given birth but it’s not nice drinking pills every day. Especially if you’re someone that’s not used to taking pills regularly. So, I don’t want to lie and say I will continue because I don’t know” (pregnant, age 21). This participant’s uncertainty reflects how daily pill-taking can feel especially daunting for those unaccustomed to chronic medication use, compounding existing emotional and physical fatigue. In addition, depression-related symptoms such as low mood, exhaustion, and a lack of motivation directly interfered with participants’ ability to adhere to their PrEP regimen. As one woman noted, “Sometimes I would not take it [PrEP] because I was not in the mood for anything” (pregnant, age 33), while another shared, “I am very hurt, and that sadness caused me to even not taking my PrEP the last weeks of my pregnancy” (postpartum, age 29). These accounts illustrate the ways in which mental health symptoms contribute to a heightened sense of pill burden that compromises PrEP adherence.

Participants also described a broader loss of motivation and a withdrawal from health-related behaviors during periods of emotional distress. For some, depressive symptoms appeared to disconnect them not only from their routine but from the very rationale for taking PrEP: “Sometimes I would ask myself what’s the reason for taking these tablets when I don’t even want tablets… I would not see myself in the clinic facilities or taking tablets. Nah!” (postpartum, age 27). This kind of cognitive–emotional disengagement reflects the interplay between hopelessness, anhedonia, and pill burden. Rather than seeing PrEP as a protective tool, some participants viewed it as one more demand in a context already defined by emotional and physical depletion. The following quoted text emphasizes the extreme contexts in which some participants find themselves: “I am a victim of 33 rapes. So, I wasn’t only taking PrEP. I took a lot of medication…I feel nauseous and I don’t feel like taking my tablets…it doesn’t feel good” (postpartum, age 27). This excerpt underscores how trauma, depression, and pill burden can interact to create a state of profound disengagement, in which self-protective behaviors like PrEP adherence become emotionally inaccessible or even aversive.

Providers offered similar observations, noting that depression and PTSD often interfere with basic self-care, suggesting that adherence to a preventive regimen would be even more challenging than maintaining activities of daily living. “Those that have PTSD…normally do not even take care of themselves. So, it will not be doable or easy to take pills if you cannot take care of yourself” (provider, age 35). Others highlighted the added burden of new motherhood and inadequate social support. One provider explained, “Even though the partner is present, [he] works during the day, leaving her struggling taking care of the baby…She’s dealing with a newborn; she’s dealing with the problems she previously had before giving birth. So, those are some of the instances that cause them to fail taking PrEP” (provider, age 28). From the provider perspective, this convergence of emotional strain, caregiving responsibilities, and lack of support underscores how PrEP adherence becomes deprioritized when women feel depleted or unsupported.

Depression and PTSD symptoms leading to PrEP non-adherence, subtheme 3: forgetfulness associated with “thinking too much”. A third pathway through which depression and PTSD symptoms disrupted PrEP adherence was through excessive rumination—described by participants as “thinking too much”—and the associated difficulty concentrating, which often led to forgetfulness. Mental preoccupation with other concerns, particularly interpersonal conflict, fear, and self-blame, displaced the mental and emotional bandwidth needed to maintain a consistent adherence routine. As one participant explained, “It affected me a lot because I used to think a lot about other things rather than taking PrEP” (postpartum, age 18). In many cases, participants understood the importance of PrEP but still found themselves distracted by the emotional toll of trauma, relationship stress, or the daily demands of motherhood.

These ruminative preoccupations made it easier to miss or forget doses, which in turn triggered guilt or fear, particularly regarding potential HIV transmission to the baby. One participant reflected, “It [the baby being infected] will hurt me because obviously I will blame myself… although there would be that particular thing that has distracted me that time. That will cause me not to take my PrEP and at the same time that might worry me” (pregnant, age 39). These ruminative cycles may deepen emotional distress and further compromise adherence. Similarly, forgetfulness not linked to “thinking too much”, such as failing to bring PrEP when staying at a partner’s home for the weekend, was frequently described in the context of broader emotional or cognitive disorganization: “Sometimes I forget taking my pills with [me] when alright with m… which means I end up not taking my pills for the whole weekend” (pregnant, age 21). These accounts highlight how both persistent overthinking and more general forgetfulness, often shaped by underlying mental health struggles, can interfere with consistent PrEP use during pregnancy.

Providers echoed these experiences, noting that mental health symptoms could impair attention and short-term memory, particularly among individuals managing the psychological aftermath of trauma. “Because of their mental state, they might forget to take it. Once someone has depression [they are] unable to think straight” (provider, age 61). Another provider highlighted the cognitive burden of living with intimate partner violence: “They are overwhelmed with fear and cannot think properly…they forget for some days, or they do not see it as a need… the only help they want is concerning their abuse” (provider, age 35). In this way, trauma and mental health symptoms divert attention away from preventive health behaviors, including PrEP, by monopolizing emotional energy and narrowing perceived priorities.

Depression and PTSD symptoms leading to PrEP non-adherence, subtheme 4: fear-related avoidance manifesting as hypersomnia. PrEP non-adherence was often facilitated by an avoidance-based coping strategy: withdrawing from daily life through excessive sleep. Sleep, described not just as rest but as a way to escape or numb distress, became a form of psychological protection from overwhelming emotions. However, this strategy also disrupted medication routines, leading to missed or delayed doses of PrEP. For many, hypersomnia appeared to serve a dual purpose, providing relief from negative mood states and also avoiding interpersonal conflict: “Yes, I prefer to sleep so that I do not come into contact with other people…so that they cannot be affected by my bad mood or else bursting out on others” (pregnant, age 28). In these instances, sleep was used both to cope with inner turmoil and to avoid harming others, underscoring the self-protective and socially protective function of withdrawal. However, this withdrawal also extended to health-promoting behaviors such as taking PrEP. The same participant explained, “I just feel like sleeping and do nothing at all. Yes, I sleep, and most of the things that I normally neglect even myself”.

Disrupted sleep routines (i.e., too much sleep and, in some cases, disturbed sleep) also contributed to poor medication adherence due to timing challenges or a general sense of inertia. For example, one participant articulated, “Sometimes when I have stress… I will say no, today I am tired I can’t do this. Because you know you didn’t take the pills. I will just avoid like that… let us do it tomorrow” (pregnant, age 16). In this way, both depression-related lethargy and stress-induced procrastination interrupted daily adherence. Similarly, for some, emotional exhaustion evolved into full withdrawal from daily functioning: “I become powerless, I lose interest in everything… I end up falling asleep. When I get out of that long sleep, I feel alright” (postpartum, age 32). Here, sleep was described almost as a reset button, a way to recover from the weight of psychological pain, but it came at the cost of adherence to behaviors that require daily consistency.

Depression and PTSD symptoms leading to PrEP non-adherence, subtheme 5: withdrawal from interactions with healthcare providers. Depression and trauma-related symptoms also led to withdrawal from providers, which in turn disrupted participants’ engagement with care and contributed to missed PrEP pickups. This withdrawal occurs in the larger context of social withdrawal that is associated with depression and PTSD. Several participants described an overwhelming reluctance to speak with clinic staff, driven by emotional fatigue, irritability, or fear of being misunderstood. One participant shared, “The other thing is that when I went to fetch my PrEP I was forced to speak because there were questions that I needed to answer. Then I was bound to answer those questions. So, I shouldn’t go” (pregnant, age 28). In this case, even routine clinical interactions felt too demanding, and avoiding the clinic altogether was seen as a way to preserve emotional energy and avoid distress.

Negative encounters with providers, whether real or anticipated, further exacerbated participants’ feelings of sadness and withdrawal. One participant explained, “I used to be alright. Not unless my sadness was caused by the nurse maybe here at the clinic” and went on to clarify, “I become disturbed and sad…I just become quiet and withdrawn. I feel sad” (postpartum, age 29). These encounters contributed to a cycle in which interpersonal stress worsened emotional symptoms, which in turn reduced motivation to attend clinic visits or engage meaningfully with staff. Another participant reflected on how this cycle played out in her interactions with providers: “So, when I am stressed, I do not feel like talking…So, I prefer to keep quiet, and they got more irritated…we would not understand each other, and I would have ended up not being helped” (postpartum, age 20). Here, the participant’s attempt to avoid conflict through silence led to further misunderstandings and frustration on both sides, highlighting how trauma symptoms can interfere with even basic healthcare communication.

While most participants described withdrawal as a barrier to care, a few noted that feeling safe and emotionally supported in the clinic could shift this pattern. One participant explained, “When I’m around people I tend to loosen up. Yes, I do talk about my feelings, and I do interact with [nurses] in a good way. I don’t lose myself” (postpartum, age 27). This suggests that, for some PPPs with depression or PTSD symptoms, positive provider interactions may temporarily alleviate withdrawal and foster engagement in care. However, such interactions appeared to be the exception rather than the rule, suggesting the need for trauma-informed, empathetic clinical environments that proactively account for and accommodate the withdrawal tendencies common among people experiencing depression and/or PTSD.

Preferred forms of PrEP support, subtheme 1: Most participants were interested in receiving professional, confidential mental health counseling to support PrEP adherence and improve emotional well-being. Given the significant mental health challenges described, most participants expressed a strong interest in receiving professional psychological support. For many, counseling was seen as a potentially valuable avenue to better cope with the emotional toll of depression, trauma, and the daily stressors associated with pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and HIV prevention. One participant shared, “I think it will be helpful because right now I don’t know how to cope on my own” (postpartum, age 22), highlighting how overwhelming emotional distress had become and the need for structured, external support. Participants emphasized that the appeal of counseling was rooted not only in a desire to feel better emotionally but also in the opportunity to speak openly without fear of judgment. One woman explained, “I will be free and will be easy for me to speak without feeling being judged so that the person can be able to advise me. How to go about in life so that my life can go alright” (pregnant, age 33). This comment illustrates the perceived potential of counseling to offer both emotional relief and practical guidance, especially for those who may feel isolated or unsure about how to move forward in their lives. Crucially, some participants made a direct link between mental health support and improved PrEP adherence. One participant articulated, “It would be a safe option because at the end of the day PrEP is something I would want to take. Having someone to talk to and help you take PrEP would be a good thing” (postpartum, age 27). This suggests that mental health services could not only alleviate emotional symptoms but also enhance adherence to HIV prevention strategies by fostering motivation, accountability, and emotional resilience.

While many participants reported turning to friends or family members during times of distress, some emphasized the unique benefits of formal counseling. Trust and confidentiality emerged as key aspects of professional counseling relationships. For example, one participant stated, “I for one would prefer to speak about it to someone… That would be a person that I have the confidence to trust… Maybe she can provide a manner where I can be able to forget about this thing so that my stress level can be minimized… I would like to go for counseling” (pregnant, age 19). Therefore, the therapeutic relationship itself was seen as beneficial because of its neutrality and emotional safety. Similarly, another participant noted, “What I like about counselling is that the person does not know you and your background. So, she will listen to me as a neutral person. I will feel free to speak freely and pour out my heart” (postpartum, age 29). For individuals facing stigma, trauma, or interpersonal difficulties, this sense of emotional distance may be perceived as protective and enabling of deeper disclosure. Participants acknowledged that informal support networks could sometimes fall short; friends might be unavailable, or their guidance might not be adequate in moments of crisis. As one participant explained, “I think it would be helpful because sometimes you go to a friend to talk and they’re not available… Also, counsellors are experienced. You might feel like giving up, but they are there to help you get through that, they know what to do in such situations” (postpartum, age 22). This underscores the perceived reliability and expertise of counselors, especially in moments when mental health challenges intensify and when clear, constructive support is needed.

Even those who had never previously accessed counseling expressed curiosity and openness. For example, one participant explained, “I have never attended counselling sessions so I don’t know what they usually look like, but I would like to get help on how to stress less and not think too much or how to stop doubting myself” (pregnant, age 21). This sentiment reflects both a gap in mental health service utilization and an unmet need—participants recognized the impact of ruminative thoughts and low self-esteem on their well-being and were eager for tools to manage these challenges.

Providers also recognized the value of mental health support in improving both psychological outcomes and HIV prevention behaviors. One provider noted, “They also get motivated after counselling when you make them realize that they don’t know their partner’s status or what they might be up to. It brings them fear of contracting HIV and reason to prevent” (provider, age 62), indicating that counseling can be a catalyst for insight and behavior change. Another stated plainly, “If the patient must see a social worker or a psychologist or even the counsellor for some reasons. That is the only support. I think that is the only support that we have for them” (provider, age 35), emphasizing the critical need for integrating these services within existing systems of care.

Preferred forms of PrEP support, subtheme 2: A minority of participants would rather confide in a peer, close friends, or family instead of counseling professionals for mental health support. While most participants expressed a strong interest in professional counseling, a minority of participants preferred to confide in close friends or family members for mental health support. These participants emphasized the emotional safety, trust, and shared lived experience that such relationships could provide, benefits they felt might be harder to replicate in clinical settings. The value of peer connection and mutual understanding was emphasized by this participant: “No, preferably a peer because there can be a mutual connection you see. Because we are sharing the same sentiment and understand what one is going through” (postpartum, age 31). This perspective suggests that empathy and shared experience may be as important as formal training when it comes to choosing a source of mental health support. Peers who have navigated similar challenges were seen as particularly well positioned to validate experiences and offer practical, relatable advice.

For some, the preference to forgo professional counseling was rooted in logistical barriers or a lack of awareness about available mental health services. One participant shared, “No, because I do not even know where to go for it and how accessible is it (counselling)… I think I am alright with my sister… It is because I trust her, and we grew up together” (pregnant, age 23). This comment reflects how accessibility concerns intersect with the desire for familiar, emotionally secure relationships. For participants like this, a trusted family member offers a ready and reliable form of emotional care in the absence of clearly accessible formal services.

Intervention considerations, subtheme 1: shared recognition of mental health as a foundation for PrEP adherence. Participants and providers alike highlighted that any mental health intervention designed to enhance PrEP adherence must explicitly aim to address the underlying psychological symptoms—such as stress, anxiety, and trauma—that interfere with consistent pill-taking. The emotional distress many pregnant and postpartum women experience was seen as not only harmful on its own but also as a key barrier to engaging in health-promoting behaviors, including taking PrEP consistently. Participants emphasized the need for a nonjudgmental, supportive space in which to process their mental health challenges. One participant noted, “I will be free and will be easy for me to speak without feeling being judged so that the person can be able to advise me. How to go about in life so that my life can go alright” (pregnant, age 33), highlighting the importance of emotional safety as a precondition for behavior change.

Providers also identified a clear link between mental health support and sustained PrEP use, suggesting that mental health screening and support should be embedded in routine care. As one provider described, “So that it can be in their minds that they really need to take PrEP… and also to monitor them accordingly and see to their mental health status continuously” (provider, age 35). This provider also acknowledged the importance of ongoing mental health monitoring, which could reinforce adherence over time. Several providers went further, arguing that effective adherence support requires first resolving—or at least addressing—upstream issues such as gender-based and intimate partner violence, as well as the lack of family support: “I think we will have to first illuminate the main issue which is gender-based violence by referring the patient to a social worker or police if they’re in danger. Once that has been dealt with, it’s easier for the patient to take their PrEP” (provider, age 29). Another provider stressed the importance of including family in the intervention, recognizing that “that’s where they get the influence of resistance from” (provider, age 62). These perspectives collectively highlight a shared understanding that mental health is foundational to PrEP adherence. Participants and providers view psychosocial support not just as an ancillary benefit but as a core feature of any effective adherence intervention.

Intervention considerations, subtheme 2: carefully considering session format. The majority of participants and providers expressed strong preferences for mental health support delivered through group-based interventions rather than individual counseling alone. The collective sharing of experiences within a peer group was described as a powerful tool for healing, empowerment, and motivation to adhere to PrEP. Participants highlighted how hearing others’ stories and perspectives helped them gain new insights and feel less isolated. One participant reflected, “The reason for that is that each person comes up with different views and can get advice also that I can apply in my situation. Maybe someone can share a story that is worse than yours and that can also transform my assumptions and give me strength to press through” (pregnant, age 28). Another shared that “sometimes when you share and listen to others it helps to forget what happened to you in the past and can guide you towards your own healing” (pregnant, age 19), emphasizing the cathartic and normalizing effects of group dialogue.

Providers similarly advocated for group formats, recognizing that peer-to-peer support could reinforce adherence in ways professional advice alone might not. One provider explained, “It is for them to meet with peers and share their experiences as well as to learn and support one another… when sharing the same sentiment, and have a mutual understanding… you tend to be motivated and adhere to that” (provider, age 35). Another suggested creating specialized groups exclusively for women on PrEP with mental health issues, which could offer a more tailored and focused environment: “Maybe have their own focus groups where they can share their own experiences” (provider, age 28). Overall, the emphasis on session format and the clear preference for group-based programming reflect the recognized value of shared experiences and collective healing in supporting mental health and PrEP adherence among pregnant and postpartum people.

Intervention considerations, subtheme 3: recognizing and attending to the logistical challenges of integrating a mental health-focused PrEP adherence intervention into antenatal care. While participants and providers recognize the potential benefits of integrating mental health interventions within the clinic setting, several logistical challenges were highlighted. Overcrowding, limited staff capacity, and varying patient schedules complicate the practical delivery of counseling or group sessions during routine antenatal and postpartum visits. Staffing shortages and clinic congestion also pose barriers. A provider described how limited personnel during shifts lead to longer patient wait times, which can reduce patients’ willingness or ability to attend additional counseling sessions: “By the time they must attend these sessions, they might not want to because some are hungry and tired” (provider, age 62). Space constraints and staggered arrival times further complicate scheduling group interventions within the usual clinic flow. One provider suggested, “Maybe if you schedule them on a different day, let them know that they’ll be attending a group session at a specific venue” (provider, age 35), emphasizing the need for intentional planning and dedicated spaces.

To navigate these challenges, providers recommended engaging clinic leadership and staff early in the planning process. One advised, “Firstly, discuss it with the facility manager. Introducing your goal and plans with the facility manager. They will decide if it’s okay and when you can meet up with the staff to introduce it to them too… Look at how it will benefit these women and how to work around time so they can attend these sessions” (provider, age 62). This collaborative approach could foster buy-in and facilitate integration within existing workflows. While integrating mental health support into clinic visits presents logistical hurdles, providers’ experiences and suggestions indicate that with strategic resource leveraging—such as aligning sessions with antenatal appointments and coordinating with clinic staff—it is a feasible and potentially impactful approach to enhancing PrEP adherence.