Disparities in Suicide Mortality Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations in Southern Brazil (2010–2019)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

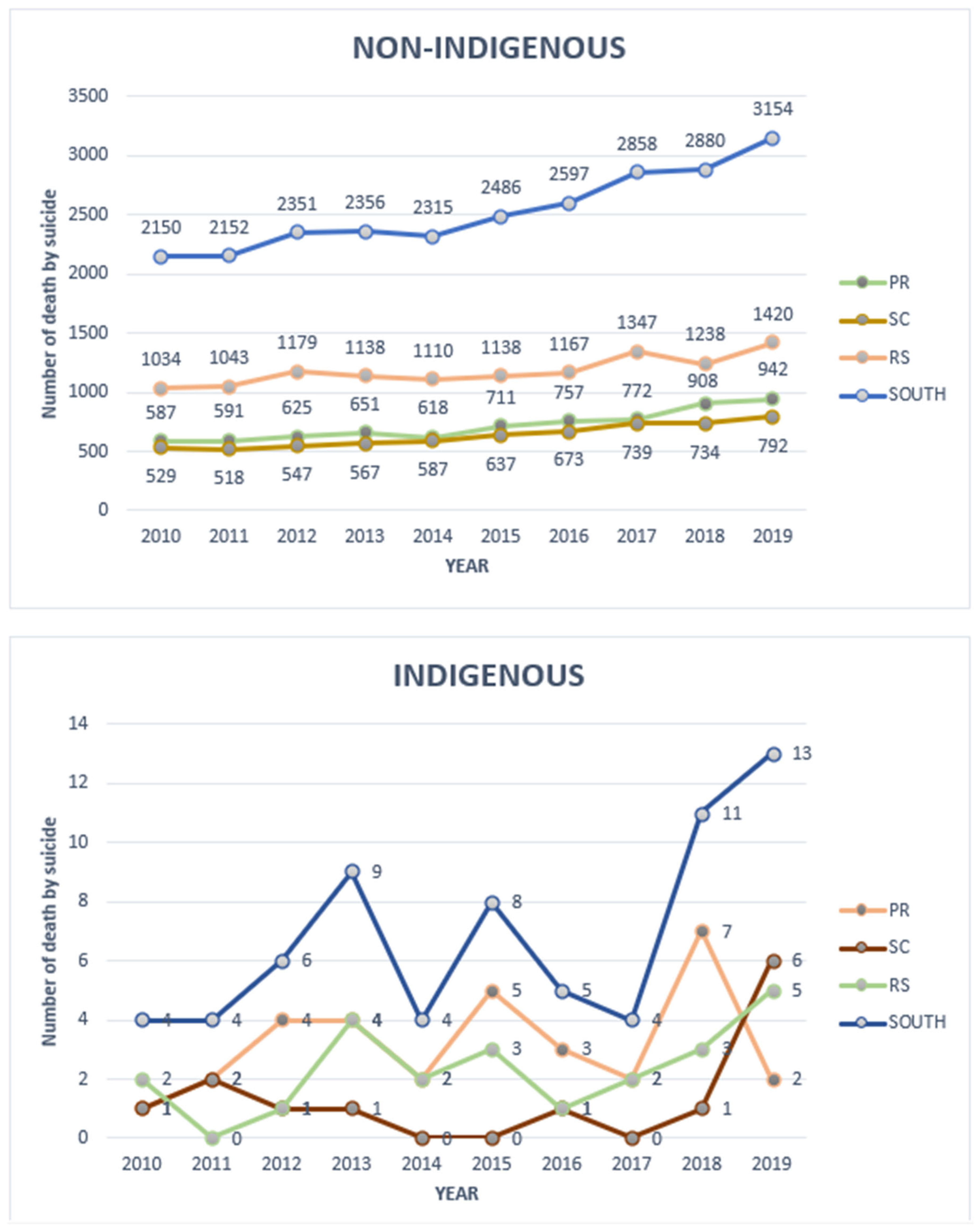

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Charlier, P.; Deo, S. The inexorable death of first peoples: An open letter to the WHO. Lancet Planetary Health 2017, 1, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, C.; Hoffman, J.S.; Crosby, A. Suicide Among Guaraní Kaiowá and Nandeva Youth in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Arch. Suicide Res. 2006, 10, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.S.B.; Oliveira, J.C.; Alvares-Teodoro, J.; Teodoro, M.L.M. Suicide and Brazilian Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2020, 44, e58. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2010: Características Gerais dos Indígenas; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2010.

- Tommasino, K. Os povos indígenas no Sul do Brasil e suas relações interétnicas. Cadernos CERU 2002, 2, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. O Brasil Indígena; FUNAI: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Mortalidade por suicídio na população indígena no Brasil, 2015 a 2018. Bol. Epidemiol. 2020, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, O.B.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.; Lozano, R.; Inoue, M. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Azuero, A.J.; Arreaza-Kaufman, D.; Coriat, J.; Tassinari, S.; Faria, A.; Castañeda-Cardona, C.; Rosselli, D. Suicide in the Indigenous Population of Latin America: A Systematic Review. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2017, 46, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, A.C.; Doran, C.M.; Tsey, K. A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting indigenous peoples. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victal, V.J.R.C.; de Aguiar, B.A.; Xavier Junior, A.F.S.; Cabral Junior, C.R. Suicide and Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. Interfaces Cient.—Saúde E Ambiente 2019, 7, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.L.P.; Orellana, J.D.Y. Disparities in suicide mortality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in Amazonas, Brazil. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2013, 62, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Suicide trends among Guaraní Kaiowá and Nandeva—Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, 2000–2005. MMWR 2007, 56, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lovisi, G.M.; Santos, S.A.; Legay, L.; Abelha, L.; Valencia, E. Suicide epidemiology in Brazil: 1980–2006. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2009, 31 (Suppl. 2), S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo-Souza, P.; Tranchitella, F.B.; Ribeiro, A.P.; Juliano, Y.; Novo, N.F. Suicide mortality in São Paulo: Characteristics and social factors (2000–2017). Sao Paulo Med. J. 2020, 138, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.D.; Guimarães, L.M.L.; Carvalho, Y.F.D.; Viana, L.D.C.; Alves, G.L.; Lima, A.C.R.; Santos, M.B.; Góes, M.A.O.; de Araújo, K.C.G.M. Spatial and temporal trends of suicide mortality in Sergipe, Brazil (2000–2015). Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2018, 40, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.J.; Naicker, K.; Loro, A.; Mulay, S.; Colman, I. Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, D.; Kim, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Gasparrini, A.; Armstrong, B.; Honda, Y.; Tobias, A.; Sera, F.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; et al. Seasonality of suicide: A multi-country observational study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.P. The Werther Effect: Suggestion and suicide. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico 2010: Terras Indígenas. Available online: https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/terrasindigenas/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- DATASUS. Health Information: TABNET. Available online: https://datasus.saude.gov.br/informacoes-de-saude-tabnet/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Lazzarini, T.A.; Gonçalves, C.C.M.; Benites, W.M.; Silva, L.F.D.; Tsuha, D.H.; Ko, A.I.; Rohrbaugh, R.; Andrews, J.R.; Croda, J. Suicide in Brazilian Indigenous communities: Clustering in children and adolescents. Rev. Saude Publica 2018, 52, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.L.P. Suicide mortality among Indigenous children in Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2019, 35 (Suppl. 3), e00019219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, S.R.; Singh, T.; Burke, A.; Stanley, B.; Mann, J.J.; Grunebaum, M.; Sublette, M.E.; Oquendo, M.A. Clinical correlates of planned and unplanned suicide attempts. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anang, P.; Naujaat Elder, E.H.; Gordon, E.; Gottlieb, N.; Bronson, M. Building on strengths in Naujaat: The process of engaging Inuit youth in suicide prevention. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2019, 78 (Suppl. 3), 1508321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendall, M.S.; Weden, M.M.; Favreault, M.M.; Waldron, H. The protective effect of marriage on survival: A review. Demography 2011, 48, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health; Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health; Department of Indigenous Health Care. Manual de Investigação/Notificação de Tentativas e Óbitos por Suicídio em Povos Indígenas; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; ISBN 978-85-334-2727-3.

| Variable | State | South Region | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | SC | RS | ||||||

| Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | |

| Population in 2010 | 25,786 | 10,418.741 | 16,242 | 6,232,194 | 33,152 | 10,660,778 | 75,180 | 27,311,713 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 8 (25%) | 1451 (20.18%) | 2 (15.38%) | 1440 (22.73%) | 3 (13.04%) | 2424 (20.48%) | 13 (19.12%) | 5315 (20.95%) |

| Male | 24 (75%) | 5741 (79.82%) | 11 (84.62%) | 4896 (77.27%) | 20 (86.96%) | 9413 (79.52%) | 55 (80.08%) | 20,050 (79.05%) |

| Age | ||||||||

| 5–9 years | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.01%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.02%) | 1 (4.55%) | 2 (0.02%) | 1 (1.49%) | 4 (0.02%) |

| 10–14 years | 3 (9.38%) | 78 (1.07%) | 1 (7.69%) | 56 (0.88%) | 0 (0.00%) | 78 (0.66%) | 4 (5.97%) | 212 (0.83%) |

| 15–19 years | 14 (43.75%) | 493 (6.79%) | 2 (15.38%) | 319 (5.03%) | 9 (40.91%) | 533 (4.51%) | 25 (37.31%) | 1345 (5.29%) |

| 20–29 years | 9 (28.13%) | 1445 (19.89%) | 2 (15.38%) | 1031 (16.27%) | 6 (27.27%) | 1650 (13.95%) | 17 (25.37%) | 4126 (16.22%) |

| 30–39 years | 4 (12.50%) | 1463 (20.14%) | 1 (7.69%) | 1114 (17.58%) | 2 (9.09%) | 1891 (15.98%) | 7 (10.45%) | 4468 (17.57%) |

| 40–49 years | 0 (0.00%) | 1422 (19.58%) | 5 (38.46%) | 1242 (19.60%) | 2 (9.09%) | 2171 (18.35%) | 7 (10.45%) | 4835 (19.01%) |

| 50–59 years | 1 (3.13%) | 1095 (15.07%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1259 (19.87%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2285 (19.31%) | 1 (1.49%) | 4639 (18.24%) |

| 60–69 years | 0 (0.00%) | 748 (10.30%) | 1 (7.69%) | 746 (11.77%) | 1 (4.55%) | 1668 (14.10%) | 2 (2.99%) | 3162 (12.43%) |

| 70 years and older | 1 (3.13%) | 519 (7.14%) | 1 (7.69%) | 568 (8.96%) | 1 (4.55%) | 1553 (13.13%) | 3 (4.48%) | 2640 (10.38%) |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| None | 0 (0%) | 265 (3.68%) | 1 (7.69%) | 130 (2.05%) | 1 (4.35%) | 275 (2.32%) | 2 (2.94%) | 670 (2.64%) |

| 1–3 years | 2 (6.25%) | 1215 (16.89%) | 3 (23.08%) | 960 (15.15%) | 11 (47.83%) | 1537 (12.98%) | 16 (23.53%) | 3712 (14.63%) |

| 4–7 years | 20 (62.5%) | 2315 (32.18%) | 5 (38.46%) | 1918 (30.27%) | 3 (13.04%) | 2526 (21.34%) | 28 (41.18%) | 6759 (26.64%) |

| 8–11 years | 4 (12.5%) | 2226 (30.94%) | 2 (15.38%) | 1891 (29.85%) | 0 (0%) | 2033 (17.17%) | 6 (8.82%) | 6150 (24.24%) |

| 12 years or more | 0 (0%) | 822 (11.43%) | 1 (7.69%) | 595 (9.39%) | 0(0%) | 665 (5.62%) | 1 (1.47%) | 2082 (8.21%) |

| Not reported | 6 (18.75%) | 351 (4.88%) | 1 (7.69%) | 842 (13.29%) | 8 (34.78%) | 4801 (40.56%) | 15 (22.06%) | 5994 (23.63%) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 22 (68.75%) | 3428 (47.65%) | 4 (30.77%) | 2230 (35.2%) | 18 (78.26%) | 5140 (43.42%) | 44 (64.71%) | 10,798 (42.57%) |

| Married | 1 (3.12%) | 2332 (32.42%) | 4 (30.77%) | 2265 (35.75%) | 1 (4.35%) | 3650 (30.84%) | 6 (8.82%) | 8247 (32.51%) |

| Divorced | 0 (0%) | 597 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 572 (9.03%) | 0(0%) | 892 (7.54%) | 0 (0%) | 2061 (8.12%) |

| Widowed | 0 (0%) | 324 (4.5%) | 1 (7.69%) | 329 (5.19%) | 0(0%) | 684 (5.78%) | 1 (1.47%) | 1337 (5.27%) |

| Not reported | 5 (15.62%) | 190 (2.64%) | 1 (7.69%) | 432 (6.82%) | 3 (13.04%) | 1209 (10.21%) | 9 (13.24%) | 1831 (7.22%) |

| Other | 4 (12.5%) | 323 (4.49%) | 3 (23.08%) | 508 (8.02%) | 1 (4.35%) | 262 (2.21%) | 8 (11.76%) | 1093 (4.31%) |

| ICD-10 code | ||||||||

| Not reported | 0(0%) | 474 (6.59%) | 0 (0%) | 413 (6.52%) | 3 (13.04%) | 637 (5.38%) | 3 (4.41%) | 1524 (6.01%) |

| Other | 1 (3.12%) | 1806 (25.10%) | 4 (30.77%) | 1227 (19.37%) | 3 (13.04%) | 2712 (22.91%) | 8 (11.76%) | 5745 (22.65%) |

| X70 | 31 (96.88%) | 4914 (68.31%) | 9 (69.23%) | 4696 (74.12%) | 17 (73.91%) | 8488 (71.71%) | 57 (83.82%) | 18,098 (71.34%) |

| Variable | State | South | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | SC | RS | Region | ||

| SEX | MALE | 1.69 (1.13–2.53) * | 0.86 (0.47–1.55) | 0.67 (0.43–1.04) | 0.99 (0.76–1.29) |

| FEMALE | 2.25 (1.13–4.52) * | 0.54 (0.13–2.15) | 0.40 (0.13–1.16) | 0.90 (0.52–1.55) | |

| AGE | 0–14 years | 12.51 (3.95–39.66) * | 5.16 (0.71–37.27) | 2.50 (0.35–17.96) | 6.02 (2.48–14.62) * |

| 15–19 years | 13.19 (7.15–20.77) * | 1.94 (0.48–7.78) | 4.21 (2.18–8.14) * | 5.87 (3.95–8.73) * | |

| 20–39 years | 2.00 (1.16–3.46) * | 0.56 (0.18–1.73) | 0.76 (0.38–1.52) | 1.08 (0.73–1.62) | |

| 40–59 years | 0.19 (0.03–1.32) | 0.98 (0.41–2.36) | 0.23 (0.06–0.91) * | 0.41 (0.21–0.82) * | |

| 60 years and older | 0.31 (0.04–2.20) | 0.78 (0.19–3.12) | 0.31 (0.08–1.23) | 0.39 (0.16–0.94) * | |

| EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT | 1–3 years of schooling | 0.39 (0.10–1.58) | 1.05 (0.39–2.80) | 1.65 (0.93–2.91) | 1.12 (0.70–1.77) |

| 4–7 years of schooling | 4.86 (3.12–7.56) * | 1.11 (0.46–2.68) | 0.47 (0.15–1.45) | 1.87 (1.29–2.71) * | |

| 8–11 years of schooling | 1.59 (0.60–4.26) | 0.76 (0.19–3.04) | - | 0.81 (0.36–1.80) | |

| 12 years or more | - | 2.63 (0.37–18.73) | - | 0.64 (0.09–4.58) | |

| Not reported | 15.66 (6.68–36.70) * | 0.22 (0.03–1.60) | 0.49 (0.24–0.99) * | 0.87 (0.52–1.46) | |

| MARITAL STATUS | Single | 0.47 (0.18–1.26) | 0.56 (0.21–1.48) | 0.95 (0.60–1.51) | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) |

| Married | 0.85 (0.32–2.26) | 1.07 (0.40–2.84) | 0.16 (0.02–1.10) | 0.59 (0.31–1.14) | |

| Widowed | 1.04 (0.15–7.39) | 1.27 (0.18–9.09) | - | 0.61 (0.15–2.44) | |

| Divorced | - | - | - | - | |

| State | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | p Value | Tau | p Value | |

| PR | 0.105 | 0.769 | 0.956 | <0.001 * |

| RS | 0.424 | 0.120 | 0.778 | 0.002 * |

| SC | 0.050 | 0.925 | 0.956 | <0.001 * |

| SOUTH | 0.556 | 0.038 | 0.944 | 0.002 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mestre, T.F.; Pelloso, F.C.; Borghesan, D.H.P.; Alarcao, A.C.J.; Borba, P.B.; Marques, V.D.; Egger, P.A.; Fontes, K.B.; Musse, F.C.C.; Labbado, J.A.; et al. Disparities in Suicide Mortality Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations in Southern Brazil (2010–2019). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091313

Mestre TF, Pelloso FC, Borghesan DHP, Alarcao ACJ, Borba PB, Marques VD, Egger PA, Fontes KB, Musse FCC, Labbado JA, et al. Disparities in Suicide Mortality Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations in Southern Brazil (2010–2019). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091313

Chicago/Turabian StyleMestre, Thiago Fuentes, Fernando Castilho Pelloso, Deise Helena Pelloso Borghesan, Ana Carolina Jacinto Alarcao, Pedro Beraldo Borba, Vlaudimir Dias Marques, Paulo Acácio Egger, Kátia Biagio Fontes, Fernanda Cristina Coelho Musse, José Anderson Labbado, and et al. 2025. "Disparities in Suicide Mortality Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations in Southern Brazil (2010–2019)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091313

APA StyleMestre, T. F., Pelloso, F. C., Borghesan, D. H. P., Alarcao, A. C. J., Borba, P. B., Marques, V. D., Egger, P. A., Fontes, K. B., Musse, F. C. C., Labbado, J. A., Valsecchi, E. A. d. S. d. S., Musse, J. L. L., de Morais, A. C. C., Pedroso, R. B., Pelloso, S. M., & Carvalho, M. D. d. B. (2025). Disparities in Suicide Mortality Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations in Southern Brazil (2010–2019). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091313