Governance in Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Global Health Governance During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Research Problem

1.3. Primary Research Question

Sub-Questions

- What limitations in global health governance affected decision-making, mortality rates, and equitable vaccine distribution during the pandemic?

- How did governance effectiveness, independent of income classification, influence pandemic response outcomes across centralized and decentralized systems?

- What policy reforms are needed to strengthen global health governance for future pandemics?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Component

2.1.1. Study Design

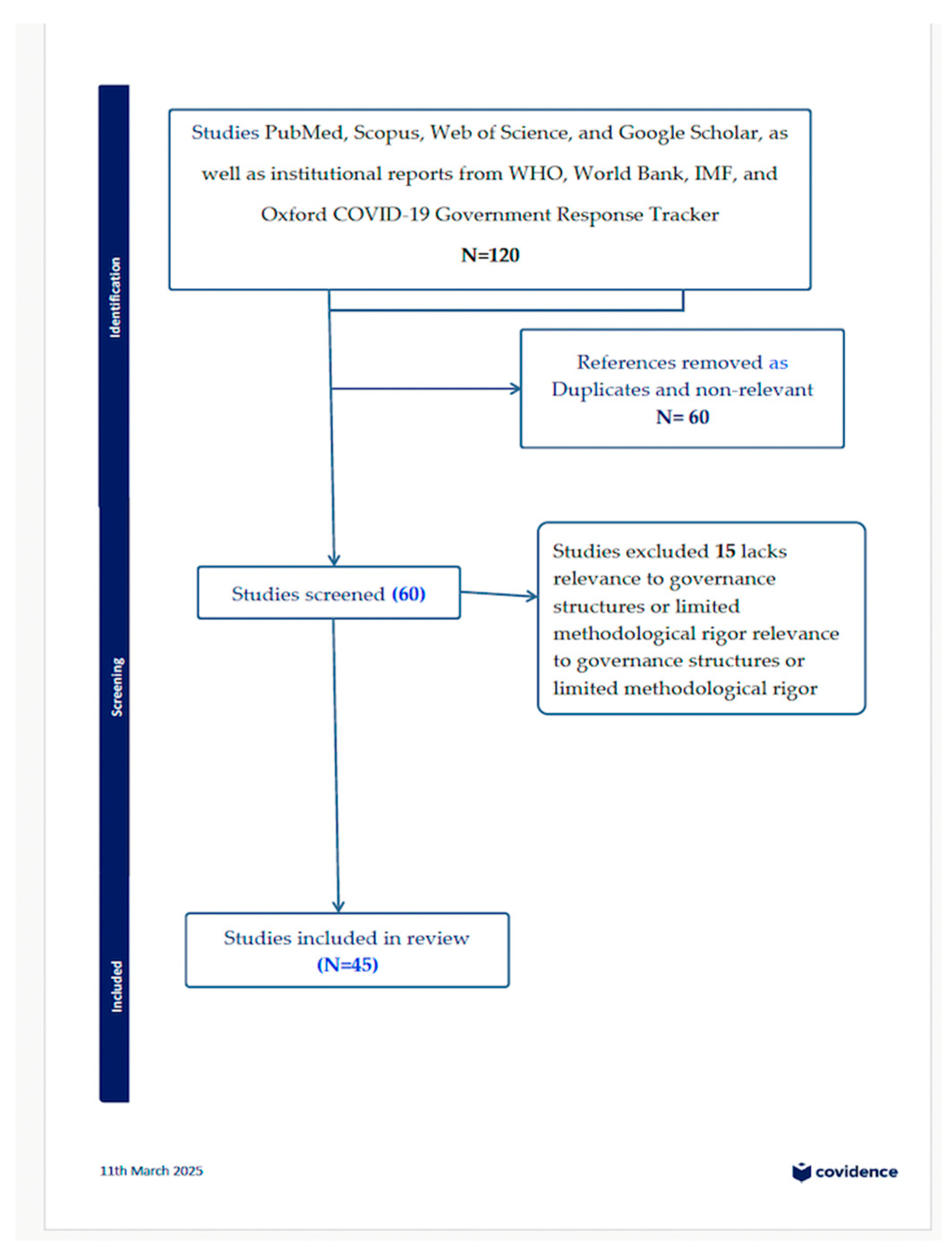

2.1.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.1.3. Data Analysis

2.2. Quantitative Component

- -

- Policy response timing, as an indicator of governance efficiency.

- -

- COVID-19 mortality rates, as a measure of governance effectiveness.

- -

- Vaccine coverage disparities, as a proxy for governance equity.

2.2.1. Data Sources and Integration

- -

- Government Effectiveness (GE): how well a government delivers public services and manages operations.

- -

- Regulatory Quality (RQ): how effectively a government creates and enforces policies that support private sector development.

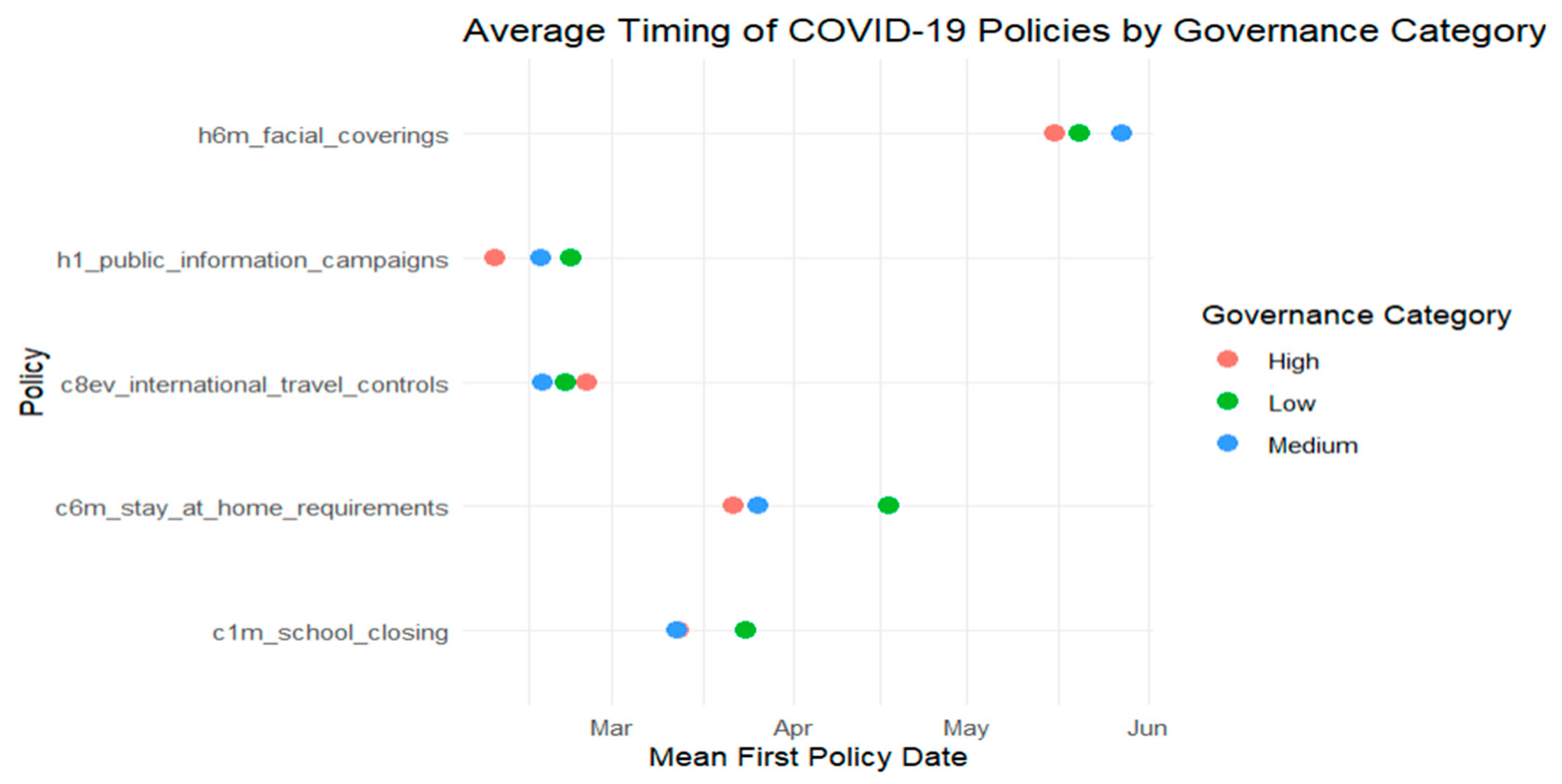

- Facial Coverings (H6M), reflecting mandates or recommendations on mask usage in public.

- Public Information Campaigns (H1), indicating whether governments launched coordinated COVID-19 awareness efforts.

- International Travel Controls (C8EV), measuring entry and exit restrictions.

- Stay-at-Home Requirements (C6M), assessing the extent of government-imposed home confinement measures.

- School Closures (C1M), capturing the timing of nationwide school shutdowns.

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative

3.1.1. Vaccine Allocation Disparities

Decision-Making Processes at Global, Regional, and National Levels

Role of COVAX, WHO, and Bilateral Agreements in Vaccine Distribution

Political and Economic Challenges in Equitable Access

Transparency in Procurement and Allocation

3.1.2. Pandemic Response Time

Effectiveness of Global Coordination Mechanisms

Factors Causing Delays in International Pandemic Response

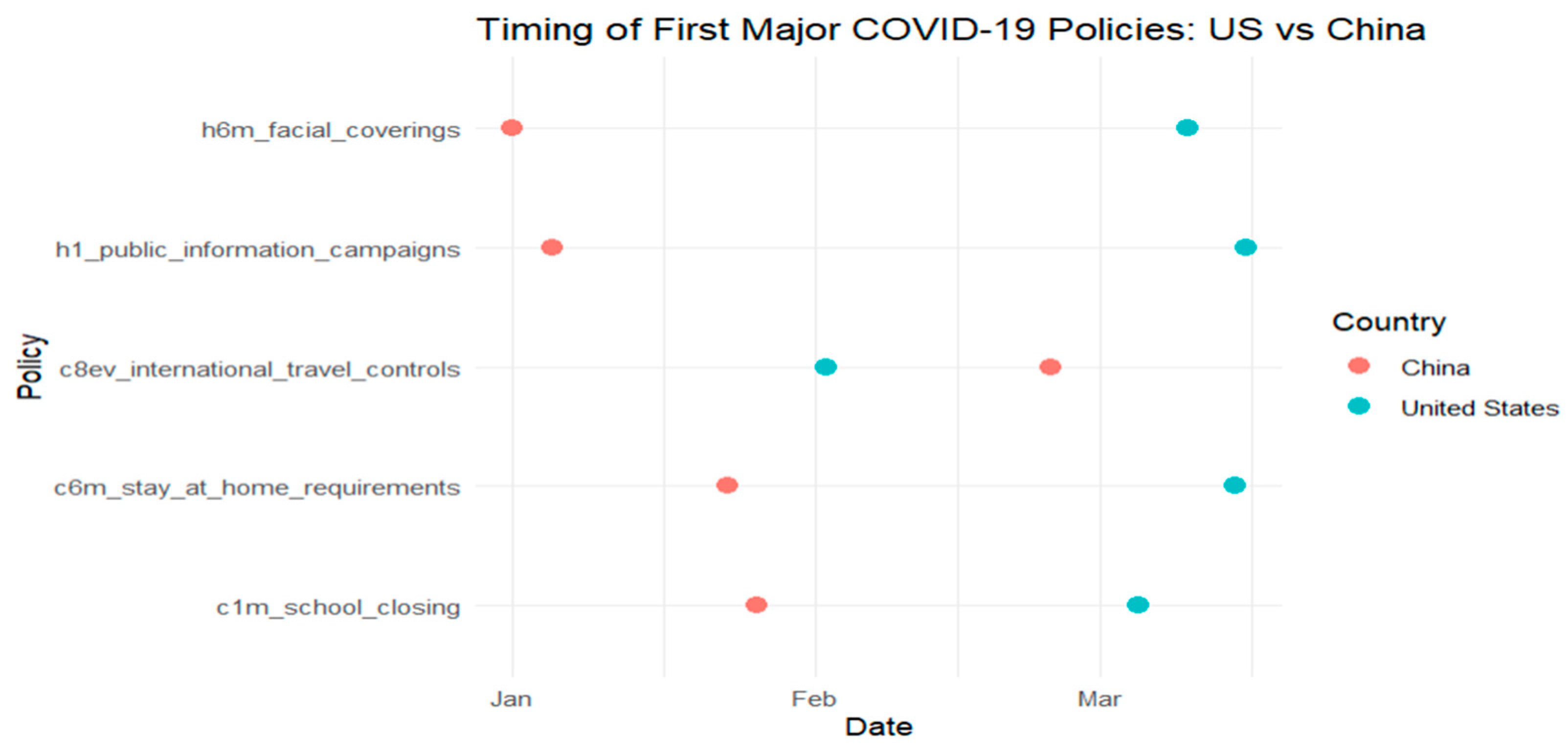

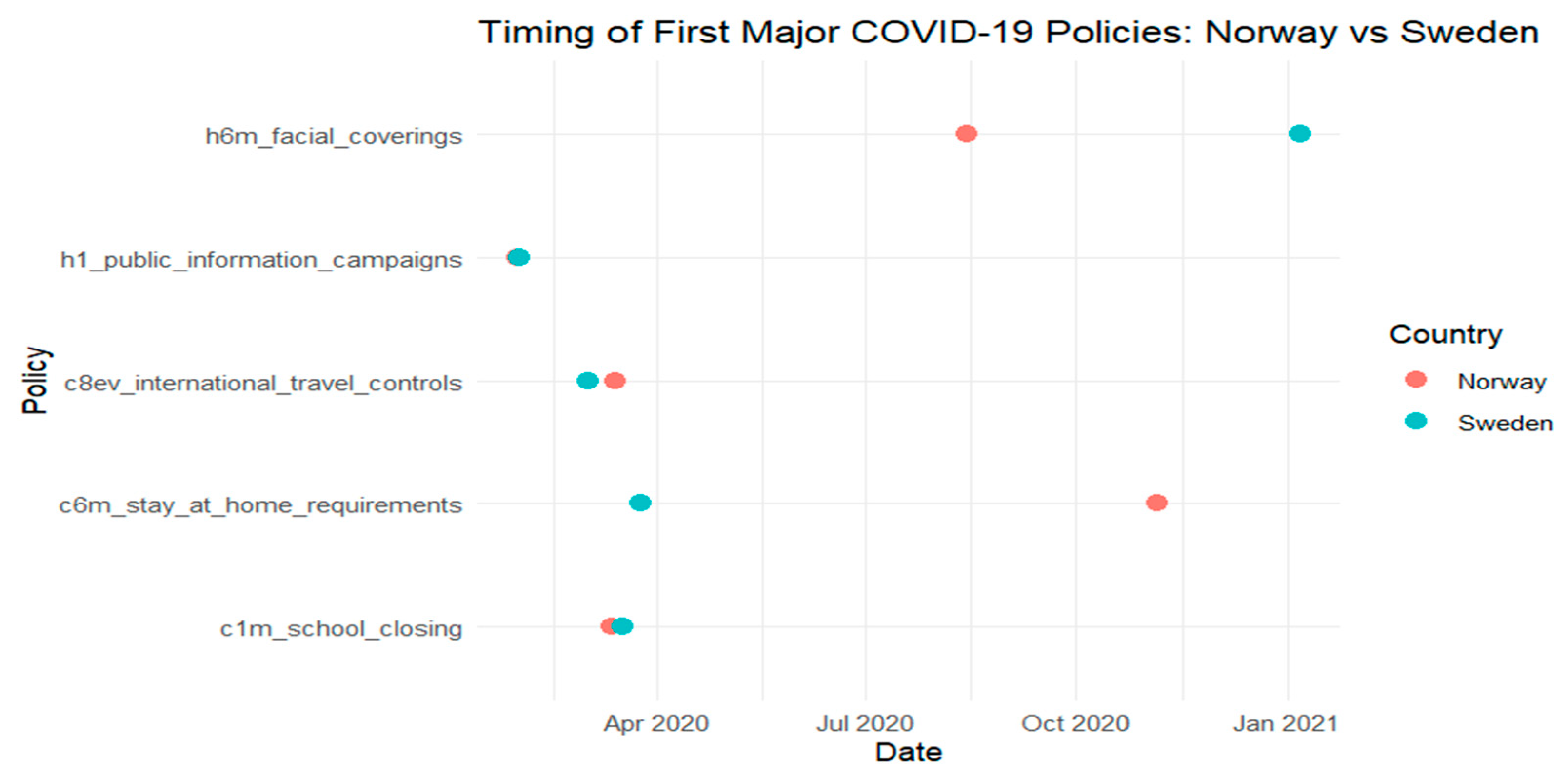

Comparison of Centralized Versus Decentralized Governance Models

3.1.3. Global Health Funding Distribution

Governance Mechanisms Behind Funding Allocation

Disparities in Funding Access Between Low- and High-Income Countries

Role of the IMF, World Bank, and Governments in Financing Global Health Responses

Accountability and Transparency in Pandemic-Related Financial Disbursements

3.1.4. Mortality Rates by Governance Model

Impact of Public Health Interventions on Mortality Rates

Governance Model’s Influence on Pandemic Response

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Governance Performance and Response Timing

- St is the probability that a country has not yet implemented the intervention by time t.

- di is the number of countries that adopted the intervention at time ti.

- ni is the number of countries still at risk (i.e., those yet to implement the intervention) just before a specific point in time, ti.

3.2.2. Governance Performance and Health Outcomes (Mortality)

- Mortality Rate (deaths per 100,000)~F (Governance, GDP Per Capita, Health, Expenditure Per Capita)

3.2.3. Governance Performance and Vaccine Equity

- Vaccine Coverage~F (Governance Performance, Per Capita Income)

3.3. Integrated Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| C6M | Stay-at-Home Requirements (OxCGRT code) |

| C8EV | International Travel Controls (OxCGRT code) |

| COVAX | COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GE | Government Effectiveness |

| GHG | Global Health Governance |

| GPL | Governance Performance Level |

| H1 | Public Information Campaigns (OxCGRT code) |

| H6M | Facial Coverings (OxCGRT code) |

| HIC | High-Income Countries |

| IHR | International Health Regulations |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IP | Intellectual Property |

| LIC | Low-Income Countries |

| LMIC | Lower-Middle-Income Countries |

| NCDs | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NPIs | Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| OxCGRT | Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker |

| PHEIC | Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| RQ | Regulatory Quality |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SSRN | Social Science Research Network |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| UMIC | Upper-Middle-Income Countries |

| WGI | Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

References

- Abu El Kheir-Mataria, W.; El-Fawal, H.; Bhuiyan, S.; Chun, S. Global health governance and health equity in the context of COVID-19: A scoping review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kickbusch, I. The political determinants of health—10 years on. BMJ 2015, 350, h81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, J.; Moon, S. Governance challenges in global health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostin, L.O.; Friedman, E.A.; Wetter, S.A. Responding to COVID-19: How to navigate a public health emergency legally and ethically. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020, 50, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://aulasvirtuales.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods-by-michael-patton.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Shulman, L.S. Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus 2005, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Fukuyama, F. What Is Governance? SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2226592 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- World Bank. Open Knowledge Repository; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/4e535db9-672d-5897-a6cd-feb4df55208f (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Available online: http://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/covid-19-government-response-tracker (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Islam, R.; Oraby, T.; McCombs, A.; Chowdhury, M.M.; Al-Mamun, M.; Tyshenko, M.G.; Kadelka, C.; Mbah, M.L.N. Evaluation of the United States COVID-19 vaccine allocation strategy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, O.J.; Shadlen, K.C.; Salcher-Konrad, M.; Pollard, A.J.; Larson, H.J.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Jit, M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: Production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet 2021, 397, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccleston-Turner, M.; Upton, H. International collaboration to ensure equitable access to vaccines for COVID-19: The ACT-Accelerator and the COVAX facility. Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyvallée, A.d.B.; Storeng, K.T. COVAX, vaccine donations and the politics of global vaccine inequity. Glob. Health 2022, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriboga, D.; Garay, J.; Buss, P.; Madrigal, R.S.; Rispel, L.C. Health inequity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cry for ethical global leadership. Lancet 2020, 395, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Yang, M.; Tan, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J. Reconceptualizing vaccine nationalism: A multi-perspective analysis on security, technology, and global competition. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 212, 123964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, S.; Erfani, P.; Goronga, T.; Hickel, J.; Morse, M.; Richardson, E.T. Global vaccine equity demands reparative justice—Not charity. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, M.; Noroozi, R.; Ghanbari-Jahromi, M.; Jalali, F.S. Inequality in the distribution of COVSID-19 vaccine: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.; Richardson, E.; Vogler, S.; Panteli, D. What Are the Implications of Policies Increasing Transparency of Prices Paid for Pharmaceuticals? World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354271/Policy-brief-45-1997-8073-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Elekyabi, S.Y. The WHO response to the pandemic coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: An evaluation under the rule of interna-tional law. J. Law. 2021, 9, 1695–1746. Available online: https://jlaw.journals.ekb.eg/article_190695_88971d4d916bda9c03674b799aa1351f.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Pacheco, M.; Fronteira, I. Essential factors on effective response at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic comment on “Experiences and implications of the first wave of the COVID-19 emergency in Italy: A social science perspective”. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2024, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; Musolino, C.; Freeman, T.; Flavel, J.; De Ceukelaire, W.; Chi, C.; Dardet, C.A.; Falcão, M.Z.; Friel, S.; Gesesew, H.A.; et al. Thinking politically about intersectoral action: Ideas, interests and institutions shaping political dimensions of governing during COVID-19. Health Policy Plan. 2024, 39, i75–i92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapon-Ntra, K.; McSharry, P.E. A global analysis of the effectiveness of policy responses to COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Das, R.P.; Muduli, K.; Raut, R.; Narkhede, B.E.; Shee, H.; Misra, A. Assessing effectiveness of humanitarian activities against COVID-19 disruption: The role of blockchain-enabled digital humanitarian network (BT-DHN). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.; Velasco, F. From centralisation to new ways of multi-level coordination: Spain’s intergovernmental response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Local Gov. Stud. 2022, 48, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, E. Multilevel responses to risks, shocks and pandemics: Lessons from the evolving Chinese governance model. J. Chin. Gov. 2020, 7, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Ye, T.; Shi, P. Coordination and cooperation are essential: A Call for a global network to enhance integrated human health risk resilience based on China’s COVID-19 pandemic coping practice. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 12, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA). Federalism in Times of Crisis: Insights from India’s COVID-19 Response; GIGA: Hamburg, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/federalism-in-times-of-crisis-insights-from-indias-covid-19-response (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Angelici, M.; Berta, P.; Costa-Font, J.; Turati, G. Divided we survive? Multilevel governance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy and Spain. Publius 2023, 53, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, D.; Batniji, R. Misfinancing Global Health: A Case for Transparency in Disbursements and Decision Making. The Lancet 2008, 372, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, C.A. Examining the governance and structure of the global health financing system using network analyses. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30 (Suppl. S5), ckaa165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosby, E. The Global Fund, governance, and accountability. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, M.M.; Chen, L. Governance and health aid from the Global Fund: Effects beyond fighting disease. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichenor, M.; Winters, J.; Storeng, K.T.; Bump, J.; Gaudillière, J.-P.; Gorsky, M.; Hellowell, M.; Kadama, P.; Kenny, K.; Shawar, Y.R.; et al. Interrogating the World Bank’s role in global health knowledge production, governance, and finance. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruger, J.P. The changing role of the World Bank in global health. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, N. The consequences of IMF conditionality for government expenditure on health. Manag. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saeed, S. From Privatization to Health System Strengthening: How Different International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Policies Impact Health in Developing Countries. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2019, 94, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Foo, C.; Verma, M.; Tan, S.Y.; Hamer, J.; van der Mark, N.; Pholpark, A.; Hanvoravongchai, P.; Cheh, P.L.J.; Marthias, T.; Mahendradhata, Y.; et al. Health financing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for universal health care: A case study of 15 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1964–e1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.Y.; Xu, R.; Ruktanonchai, N.; Saucedo, O.; Childs, L.M.; Jalali, M.S.; Rahmandad, H.; Ghaffarzadegan, N. Why similar policies resulted in different COVID-19 Outcomes: How responsiveness and culture influenced mortality rates. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susumu, A. Good democratic governance can combat COVID-19-excess mortality analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 83, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales Crespo, K.A.; Rocha, J.; Vázquez, M.; Peixoto, V.; Dias, S. The COVID-19 policy response in Spain and Portugal: A study of measures to slow down infection rate. Eur. J. Public Health. 2021, 31 (Suppl. S3), ckab165-045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020, 5, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevdovski, D.; Jolakoski, P.; Stojkoski, V. The Impact of State Capacity on the Cross-Country Variations in COVID-19 Vaccination Rates. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2022, 22, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Myers, M.; Varpilah, S.T.; Dahn, B.T. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet. 2015, 385, 1910–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; 44p, ISBN 9789241596077. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Boxell, L.; Conway, J.; Gentzkow, M.; Thaler, M.; Yang, D. Political regimes and deaths in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Leung, G.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Matsoso, M.P.; Ihekweazu, C.; Abbasi, K. COVID-19: How a virus is turning the world upside down. BMJ 2020, 3, 369:m1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Target Research Question | Areas of Analysis | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Allocation Disparities | Sub-question 1: Governance limitations affecting vaccine equity | Global, regional, and national decision-making processes | Analyze which actors influenced vaccine allocation and the frameworks guiding those decisions. |

| Role of COVAX and bilateral agreements | Evaluate the effectiveness of global initiatives and bilateralism in equitable distribution. | ||

| Political and economic access barriers | Investigate how geopolitical factors, funding disparities, and national interests influenced vaccine accessibility. | ||

| Transparency in procurement and allocation | Examine transparency in vaccine procurement and its impact on equitable access. | ||

| Pandemic Response Time | Sub-question 1: Governance limitations impacting response time | Effectiveness of global coordination mechanisms (e.g., WHO emergency declarations) | Evaluate how international health entities and national governments coordinated pandemic responses. |

| Delays in international pandemic response | Identify structural, political, and logistical barriers that led to delays in response activation. | ||

| Centralized vs. decentralized governance models | Analyze how different governance structures impacted response efficiency. | ||

| Role of legal frameworks (e.g., IHR) | Examine how legal tools helped or hindered rapid responses. | ||

| Global Health Funding Distribution | Sub-question 1: Governance limitations impacting funding distribution | Governance mechanisms behind funding allocation | Investigate the decision-making processes guiding pandemic funding. |

| Disparities in funding distribution | Assess equity in access to financial resources across countries. | ||

| Role of IMF, World Bank, and national governments | Analyze contributions and limitations of key financial institutions. | ||

| Accountability and transparency | Evaluate mechanisms used to monitor and track financial flows. | ||

| Mortality Rates by Governance Model | Sub-question 2: How different governance models influenced pandemic outcomes? | Impact of public health interventions on mortality rates | Assess the effectiveness of public health strategies in reducing deaths. |

| Influence of governance models on emergency response | Examine the extent to which governance models supported or hindered healthcare delivery. | ||

| Case studies of successful vs. failed approaches | Compare countries with effective vs. ineffective governance outcomes. |

| Section | Variable/Outcome | Statistical Test | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Governance Performance Level (GPL) and Response Timing | School Closure Timing | Kaplan–Meier survival analysis; log-rank test to compare groups. | Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) and World Governance Indicators (WGIs). |

| 2. Governance Performance Level (GPL) and Health Outcomes | COVID-19 Mortality Rate | Ordinary Least Squares (OLSs) regression. Breusch–Pagan (heteroskedasticity), Durbin–Watson (autocorrelation). | Data: WHO COVID-19 Mortality Database, World Bank, and WGI |

| 3. Governance Performance Level (GPL) and Vaccine Equity | Vaccine Coverage Across Income Groups | One-way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc comparisons. | Data: Our World in Data, UNICEF, GAVI, WHO, and COVAX reports. |

| Vaccine Coverage across Governance Performance Levels (GPLs) | OLS regression with governance dummies and GDP controls. | Data: WHO, World Bank, and WGI |

| Vaccine Allocation Disparities | |

| Wouters et al., 2021 [13] | The study aims to analyze the barriers to global COVID-19 vaccine access by assessing challenges in production, affordability, allocation, and deployment and exploring potential policy solutions. |

| Eccleston-Turner and Upton (2021) [14] | Evaluates global vaccine-sharing mechanisms |

| de Bengy Puyvallée and Storeng, 2022 [15] | Examines how political interests shaped vaccine distribution under COVAX, leading to disparities in access. |

| Chiriboga et al., 2020 [16] | It calls for ethical global leadership to address health inequities. |

| Harman S. et al., 2021 [18] | Critiques of global vaccine inequities, arguing that donor-based approaches reinforce dependency and advocating for reparative justice through intellectual property waivers and local manufacturing. |

| Bayati et al., 2022 [19] | Factors affecting inequality in the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine (macro-level and micro-level factors). |

| Web et al., 2022 [20] | The study examines the lack of transparency in pharmaceutical pricing, highlighting how confidential agreements, undisclosed profit margins, and information asymmetry disadvantage low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in vaccine procurement. |

| Pandemic Response Time | |

| Elekyabi, S.Y. 2020 [21] | To evaluate the role and response of the World Health Organization (WHO) during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of international law, with a focus on legal authority, accountability, transparency, and compliance mechanisms. |

| Cortes, Pacheco, and Fronteira, 2024 [22] | To emphasize the role of social, political, and economic factors and argue for the integration of social science insights into pandemic preparedness and response strategies. |

| Baum, F., et al. 2024 [23] | The primary objective of the study is to investigate how political factors influenced intersectoral actions during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the interplay of ideas, interests, and institutions. |

| Agyapon-Ntra and McSharry, 2023 [24] | To empirically assess the effectiveness of government non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) on COVID-19 spread and compliance, considering demographic and socioeconomic factors globally. |

| Navarro, C., and Velasco, F., 2022 [26] | The study argues that Spain’s response to COVID-19 marked a shift from centralized control to innovative multilevel coordination, revealing the adaptability of its decentralized governance. It highlights how crisis management required both recentralization and cooperative intergovernmental mechanisms |

| Ahmad, E. 2020 [27] | To examine China’s multilevel governance and fiscal framework in responding to COVID-19 and to compare with international responses across governance models. |

| Sun, Y., et al., 2021 [28] | The study aims to extract lessons from China’s COVID-19 response—especially in government action, transmission pathways, and medical resource allocation—and to advocate for the creation of a global network that enhances resilience to health risks through international coordination and cooperation. |

| GIGA Focus Asia, 2025 [29] | To examine India’s COVID-19 response from a federal governance perspective, using case studies from four states (Kerala, Odisha, Karnataka, and Uttar Pradesh), and assess how decentralization, leadership, coordination, and community engagement influenced crisis outcomes. |

| Angelici et al., 2023 [30] | To examine how different multilevel governance strategies—centralized (Spain) versus decentralized (Italy)—affected pandemic outcomes (infections, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, deaths) during the first wave of COVID-19. |

| Global Health Funding Distribution | |

| Sridhar and Batniji, 2008 [31] | To assess how major global health donors allocated funds and whether disbursements are aligned with global disease burden. It advocates for transparency and improved priority setting in global health governance |

| Fergus, 2020 [32] | To explore the structure of global health aid by analyzing financial flows and relationships between funders, intermediaries, and recipients over 1990–2017, identifying key gaps and governance challenges |

| Goosby E., 2019 [33] | The article explores the governance mechanisms of the Global Fund, emphasizing its effectiveness not only in fighting diseases but also in contributing to enhanced governance at the country level. |

| Kavanagh and Chen, 2019 [34] | To assess how the Global Fund’s governance model has influenced civil society participation, political accountability, and broader governance practices in recipient countries |

| Tichenor, 2021 [35] | To critically examine how the World Bank shapes global health through its roles in knowledge production, governance, and financing, and to develop a research agenda that promotes greater accountability and responsiveness to local health priorities. |

| Ruger, 2005 [36] | To trace the evolution of the World Bank’s involvement in global health from its original post-WWII reconstruction mission to its present role as the largest external health funder and to analyze the theoretical, political, and institutional shifts that shaped this transition. |

| Moosa, N., 2018 [37] | To assess whether IMF loan conditionalities have a positive or negative impact on government health expenditure and to argue that these conditionalities tend to reduce such expenditure, despite IMF claims. |

| Sobhani, S., 2019 [38] | To evaluate the historical and current impacts of IMF and World Bank policies on health outcomes in developing countries, especially focusing on privatization and health system strengthening (HSS) initiatives |

| Chuan De Foo, et al. 2023 [39] | To provide an overview of health financing policies adopted in 15 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, develop a framework for resilient health financing, and use the pandemic as a case to advocate for progress towards universal health coverage (UHC). |

| Mortality Rates by Governance Model | |

| Fukuyama, F., 2020 [9] | To argue that the quality of governance, rather than regime type (democracy vs. autocracy), is the key determinant of a country’s effectiveness in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Lim et al., 2023 [40] | To examine the reasons behind varying COVID-19 mortality outcomes among countries that implemented similar containment policies, with a focus on how responsiveness and national culture influenced these differences |

| Source | Df | Sum of Squares (SS) | Mean Square (MS) | F Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance Performance Level | 1 | 27,328.314 | 12,061.35 | 5.85 | 0.01 |

| Residuals | 139 | 35,351.306 | 4401.86 |

| Adjusted R2 | Reference Category | |||

| Mortality/100,000 | 0.72 | Medium Governance Performance Level | ||

| Independent Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | p-value |

| Intercept | 175.01 | 35.64 | 4.91 | <0.001 |

| Low Governance Performance Level | −15.21 | 6.20 | −2.45 | 0.018 |

| High Governance Performance Level | −88.55 | 29.39 | −3.01 | 0.004 |

| Income per Capita | −0.24 | 0.06 | −4.01 | <0.001 |

| Health Expenditure per Capita | −0.16 | 0.07 | −2.28 | 0.025 |

| Income Group | Count | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIC | 27 | 135 | 128 | 31 |

| LMIC | 55 | 202 | 201 | 75 |

| UMIC | 55 | 230 | 188 | 123 |

| HIC | 59 | 482 | 629 | 217 |

| Degrees Freedom | Sum Squares | Mean Squares | F Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Group (Between Groups) | 3 | 3,443,472 | 1,147,824 | 56.87 | 0 |

| Residuals (Within Groups) | 192 | 3,868,283 | 20,147 |

| Classification | Difference | Lower | Upper | p-Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIC-HIC | −347.11 | −432.59 | −261.64 | 0.00 |

| LMIC-HIC | −280.11 | −349.06 | −211.16 | 0.00 |

| UMIC-HIC | −251.84 | −320.79 | −182.89 | 0.00 |

| LMIC-LIC | 67.01 | −19.44 | 153.45 | 0.02 |

| UMIC-LIC | 95.27 | 8.83 | 181.71 | 0.02 |

| UMIC-LMIC | 28.26 | −41.89 | 98.41 | 0.07 |

| Dependent Variable | Adj R-Square | ||

| Vaccine Coverage | 0.68 | ||

| Independent Variables | Coefficient Estimate | Standard Error | T-Statistic |

| Intercept | 489.9 | 47.13 | 10.39 |

| Governance Low | −274.5 | 41.61 | −6.60 |

| Governance High | 323.38 | 46.09 | 7.02 |

| Income Per Capita | 2.3 | 0.60 | 3.83 |

| Quantitative Findings | Qualitative Insights | Integrated Interpretation |

| 1-Vaccine Allocation Disparities | ||

| The analysis of vaccine doses secured per 1000 population across income groups revealed stark disparities. ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests confirmed statistically significant differences (p < 0.001), with high-income countries securing a mean of 482 doses compared to 135 for low-income countries. OLS regression demonstrated that governance performance level, independent of income, significantly influenced vaccine coverage. A low-governance classification was associated with 274 fewer doses per 1000 (p < 0.01). | The purposive review highlighted political and economic barriers to equitable vaccine access. Studies emphasized how high-income countries engaged in vaccine nationalism and bilateral deals, bypassing multilateral initiatives like COVAX [15,16]. Transparency deficits in procurement and opaque pharmaceutical pricing disadvantaged LMICs [31]. Governance gaps in global coordination were a recurring theme. | The quantitative disparities are supported by qualitative evidence of systemic governance failures, including fragmented procurement frameworks and geopolitical self-interest. This triangulation confirms that governance capacity, regardless of income, influenced vaccine equity. |

| 2-Pandemic Response Time | ||

| Kaplan Meier survival analysis showed that high-governance performance level countries implemented school closures and other interventions significantly earlier than low-governance countries (log-rank p = 0.007). ANOVA tests also showed a statistically significant difference in intervention timing across governance categories (p = 0.01). | Elekyabi [21] and Ahmad [27] stressed the WHO’s limited authority to enforce early action and the importance of centralized governance models in enabling swift response. Comparative case studies from China, Spain, and Italy illustrated how coordination mechanisms and institutional trust facilitated or hindered timely interventions. | The survival analysis quantitatively confirms the narrative that governance quality dictates response speed. Centralized, high-capacity systems responded faster, validating the qualitative critique of decentralized inefficiencies and political fragmentation. |

| 3-Global Health Funding Distribution | ||

| Quantitative analysis was excluded due to statistically insignificant findings. This may reflect the nature of the data, which primarily captured donor-based funding, often allocated independently of governance performance. | Studies identified conditionalities from institutions like the IMF as barriers to flexible funding [37,38]. Governance structures within the Global Fund and Gavi promoted inclusivity but often faced power asymmetries. Lack of transparency in donor disbursements remained a persistent issue [37] | Qualitative evidence suggests that weak institutional governance created administrative bottlenecks, limiting timely access to available pandemic-related funding. |

| 4-Mortality Rates by Governance Performance Level | ||

| OLS regression showed that governance performance level had a strong and significant effect on COVID-19 mortality. High-governance countries had 88.6 fewer deaths per 100,000 than low-governance ones, with an R-squared of 0.72, indicating high model fit. | Lim [40] and Fukuyama [9] emphasized that responsive governance, institutional trust, and public engagement were crucial in mitigating mortality. Countries like South Korea and New Zealand demonstrated that timely, coordinated public health interventions reduced death rates despite differing income levels. | The quantitative evidence validates qualitative case studies showing that legitimacy, trust, and agility in governance significantly shaped mortality outcomes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdel-Motaal, K.A.; Chun, S. Governance in Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Global Health Governance During COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081305

Abdel-Motaal KA, Chun S. Governance in Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Global Health Governance During COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081305

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdel-Motaal, Kadria Ali, and Sungsoo Chun. 2025. "Governance in Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Global Health Governance During COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081305

APA StyleAbdel-Motaal, K. A., & Chun, S. (2025). Governance in Crisis: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Global Health Governance During COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081305