Perception of Concern and Associated Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Epidemiological Survey in a Brazilian Municipality

Abstract

1. Introduction

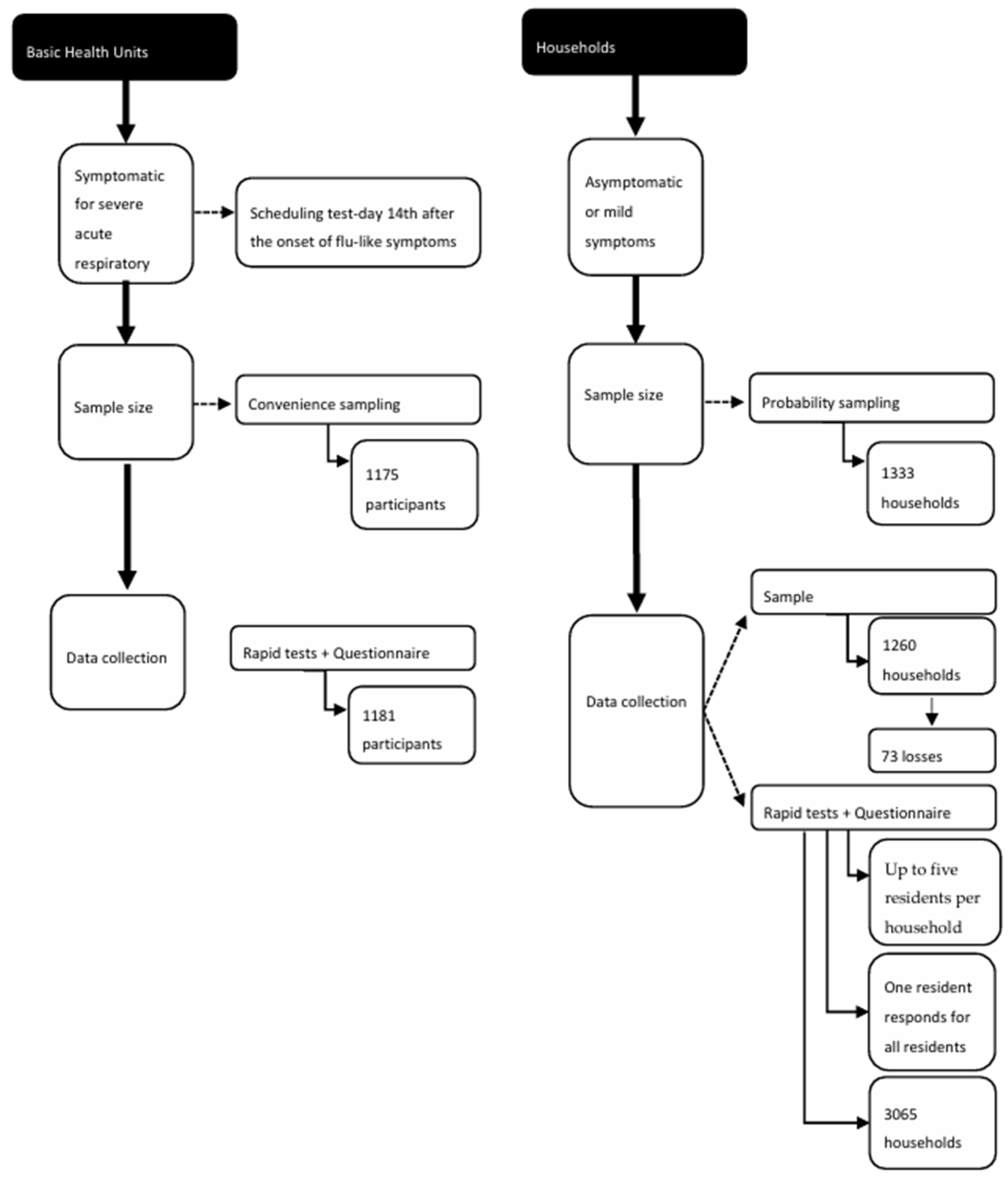

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Talevi, D.; Socci, V.; Carai, M.; Carnaghi, G.; Faleri, S.; Trebbi, E. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Psichiatr. 2020, 55, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Heitzman, J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzotto, A.D.B.; Oliveira, A.M.; Elkis, H.; Cordeiro, Q.; Buchain, P.C. Psychosocial characteristics. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, M.J.; Lino, C.M.; Tenani, C.F.; Barbosa, A.P.; Latorre, M.d.R.D.d.O.; Marchi, E. COVID-19 Mortality among Hospitalized Patients: Survival, Associated Factors, and Spatial Distribution in a City in São Paulo, Brazil, 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. New Poll: COVID-19 Impacting Mental Well-Being: Americans Feeling Anxious, Especially for Loved Ones; Older Adults Are Less Anxious. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-amer#:~:text=WASHINGTON%2C%20D.C.%20%E2%80%93%20Nearly%20half%20of,family%20and%20loved%20ones%20getting (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Sonderskov, K.M.; Dinesen, P.T.; Santini, Z.I.; Østergaard, S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020, 32, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, T.W.; Nunes, M.L. Social and environmental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children. J. Pediatr. Rio J. 2022, 98 (Suppl. 1), S4–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fisicaro, F.; Lanza, G.; Concerto, C.; Rodolico, A.; Di Napoli, M.; Mansueto, G.; Cortese, K.; Mogavero, M.P.; Ferri, R.; Bella, R.; et al. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A “Pandemic Within a Pandemic”. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1458, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Schuch, J.B.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A.; da Silva, J.A.; de Paiva Teixeira, L.E.P.; Antonelli-Ponti, M.; Bastos, S.; Mármora, C.H.C. Evaluation of fear and peritraumatic distress during COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2020, 10, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, A. Why worry? The cognitive function of anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1990, 28, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstone, G.L.; Parker, G.B.; Mitchell, P.B.; Malhi, G.S.; Wilhelm, K.A.; Austin, M.P. A Brief Measure of Worry Severity (BMWS): Personality and clinical correlates of severe worriers. J. Anxiety Disord. 2005, 19, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnut, M.; Harati, S.; Paredes, P.; Khan, Y.; Foudeh, A.; Kim, J. Stress Markers for Mental States and Biotypes of Depression and Anxiety: A Scoping Review and Preliminary Illustrative Analysis. Chronic. Stress 2021, 5, 247054702110003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.C.M.d.; Restrepo-Mendez, M.C.; Costa, J.C.; Ewerling, F.; Hellwig, F.; Ferreira, L.Z.; Ruas, L.P.V.; Joseph, G.; Barros, A.J.D. Measurement of social inequalities in health: Concepts and methodological approaches in the Brazilian context. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2018, 27, e000100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Survey Tool and Guidance: Rapid, Simple, Flexible Behavioural Insights on COVID-19. May 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2020-696-40431-54222 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Batista, M.J.; Lino, C.M.; Tenani, C.F.; Zanin, L.; Correia da Silva, A.T.; Nunes Lipay, M.V. Seroepidemiological investigation of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Jundiaí, São Paulo, Brazil. Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística. Jundiaí (SP)|Cidades E Estados|IBGE. ibge.gov.br. Available online: https://ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/sp/jundiai.html (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Alexandre, N.M.C.; Gallasch, C.H.; Lima, M.H.M.; Rodrigues, R.C.M. Reliability in the development and evaluation of measurement instruments in the health field. Rev. Eletr. Enferm. 2013, 15, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salas Quijada, C.; López-Contreras, N.; López-Jiménez, T.; Medina-Perucha, L.; León-Gómez, B.B.; Peralta, A.; Arteaga-Contreras, K.M.; Berenguera, A.; Gonçalves, A.Q.; Horna-Campos, O.J.; et al. Social Inequalities in Mental Health and Self-Perceived Health in the First Wave of COVID-19 Lockdown in Latin America and Spain: Results of an Online Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghrebi, A.H. Risk factors for attempting suicide during the COVID-19 lockdown: Identification of the high-risk groups. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Röthke, N.; Günthner, L.; Stoffers-Winterling, J.; Tüscher, O.; Coenen, M.; Rehfuess, E.; Schwarzer, G.; Binder, H.; Schmucker, C.; et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arilha, M.; Carvalho, A.P.; Forster, T.A.; Rodrigues, C.V.M.; Briguglio, B.; Serruya, S.J. Women’s mental health and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and inequalities. Front. Glob Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1414355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, V.C.d.; Morais, A.C.; Carvalho, E.S.d.S.; Santos, J.d.S.d.; da Silva, I.A.R.; Teixeira, J.B.C. Health of the black population in the pandemic context of COVID-19: A narrative review. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 2306–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwarcwald, C.L.; Damacena, G.N.; Barros, M.B.D.A.; Malta, D.C.; De Souza Júnior, P.B.; Azevedo, L.; Machado, Í.E.; Lima, M.G.; Romero, D.; Gomes, C.S.; et al. Factors affecting Brazilians’ self-rated health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cad. Saude Publica 2021, 37, e00182720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, K.B.; Ribeiro, A.F.; Veras, M.A.S.M.; de Castro, M.C. Social inequalities and COVID-19 mortality in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.C.; Hartwig, F.P.; Horta, B.L.; Silveira, M.F.; Struchiner, C.J.; Vidaletti, L.P. SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in Brazil: Results from two successive nationwide serological household surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1390–e1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yan, M.Z.; Li, X.; Lau, E.H.Y. Sequelae of COVID-19 among previously hospitalized patients up to 1 year after discharge: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection 2022, 50, 1067–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilović-Lagarija, Š.; Eitze, S.; Skočibušić, S.; Musa, S.; Stojisavljević, S.; Šabanović, H.; Dizdar, F.; Palo, M.; Nitzan, D.; de Arriaga, M.T.; et al. Behavioral insights during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina: The role of trust, health literacy, risk and fairness perceptions in compliance with public health and social measures. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Household | UBS | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 804 | 64.3 | 752 | 63.7 | 1556 | 64.0 |

| Male | 447 | 35.7 | 429 | 36.3 | 876 | 36.0 | |

| Age (years) | 18 to 39 | 333 | 26.6 | 624 | 52.8 | 957 | 39.4 |

| 40 to 59 | 497 | 39.7 | 441 | 37.3 | 638 | 26.2 | |

| ≥60 | 414 | 33.1 | 116 | 9.8 | 530 | 21.8 | |

| NR | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.2 | |

| Skin color | Black | 69 | 5.5 | 73 | 6.2 | 82 | 3.4 |

| Mixed race | 244 | 19.5 | 296 | 25.1 | 340 | 14.0 | |

| White | 905 | 72.3 | 794 | 67.2 | 1699 | 69.9 | |

| Yellow | 30 | 2.4 | 10 | 0.8 | 40 | 1.6 | |

| NR | 3 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.7 | 11 | 0.5 | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | 16 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 0.7 |

| Up to elementary school | 292 | 23.3 | 146 | 12.4 | 438 | 18.0 | |

| Up to high school | 446 | 35.7 | 562 | 47.6 | 1008 | 41.4 | |

| Complete higher education/Postgraduation | 496 | 39.6 | 458 | 38.8 | 954 | 39.2 | |

| NR | 1 | 0.1 | 15 | 1.3 | 16 | 0.7 | |

| Household income | <1 MW | 82 | 6.6 | 56 | 4.7 | 138 | 5.7 |

| 1 to 2 MW | 197 | 15.7 | 214 | 18.1 | 411 | 16.9 | |

| 2 to 3 MW | 241 | 19.3 | 218 | 18.5 | 432 | 17.8 | |

| 3 to 4 MW | 227 | 18.1 | 243 | 20.6 | 270 | 11.1 | |

| ≥5 MW | 355 | 28.4 | 337 | 28.5 | 692 | 28.5 | |

| No income | 11 | 0.9 | 13 | 1.1 | 24 | 1.0 | |

| NR | 138 | 11.0 | 100 | 8.5 | 238 | 9.8 | |

| Highest educational attainment of the household | Illiterate | 7 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.3 |

| Up to elementary school | 85 | 6.8 | 28 | 2.4 | 113 | 4.6 | |

| Up to high school | 358 | 28.6 | 380 | 32.2 | 738 | 30.3 | |

| Complete higher education/Postgraduation | 783 | 62.6 | 727 | 61.6 | 1510 | 62.1 | |

| NR | 18 | 1.4 | 46 | 3.9 | 64 | 2.6 | |

| Health professional in the household | Yes | 225 | 18.0 | 284 | 24.0 | 509 | 20.9 |

| No | 1026 | 82.0 | 897 | 76.0 | 1923 | 79.1 | |

| Total | 1251 | 100 | 1181 | 100 | 2432 | 100 | |

| Household | UBS | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Fear of being very alone | Does not worry me | 747 | 59.7 | 538 | 45.6 | 1285 | 52.8 |

| Worries me a little | 262 | 20.9 | 233 | 19.7 | 495 | 20.4 | |

| Worries me a lot | 242 | 19.3 | 410 | 34.7 | 652 | 26.8 | |

| Fear of losing someone close due to the disease | Does not worry me | 134 | 10.7 | 53 | 4.5 | 187 | 7.7 |

| Worries me a little | 110 | 8.8 | 43 | 3.6 | 153 | 6.3 | |

| Worries me a lot | 1007 | 80.5 | 1085 | 91.9 | 2092 | 86.0 | |

| Fear of a family member/friend contracting coronavirus | Does not worry me | 93 | 7.4 | 60 | 5.1 | 153 | 6.3 |

| Worries me a little | 125 | 10.0 | 70 | 5.9 | 195 | 8.0 | |

| Worries me a lot | 1033 | 82.6 | 1051 | 89.0 | 2084 | 85.7 | |

| Experiencing financial difficulties | Does not worry me | 632 | 50.5 | 495 | 41.9 | 1127 | 46.3 |

| Worries me a little | 243 | 19.4 | 202 | 17.1 | 445 | 18.3 | |

| Worries me a lot | 376 | 30.1 | 484 | 41.0 | 860 | 35.4 | |

| School closure | Does not worry me | 221 | 17.7 | 226 | 19.1 | 447 | 18.4 |

| Worries me a little | 209 | 16.7 | 194 | 16.4 | 403 | 16.6 | |

| Worries me a lot | 821 | 65.6 | 761 | 64.4 | 1582 | 65.0 | |

| Fear of catching coronavirus | Does not worry me | 167 | 13.3 | 254 | 21.5 | 421 | 17.3 |

| Worries me a little | 173 | 13.8 | 140 | 11.9 | 313 | 12.9 | |

| Worries me a lot | 911 | 72.8 | 787 | 66.6 | 1698 | 69.8 | |

| Fear of becoming unemployed | Does not worry me | 571 | 45.6 | 330 | 27.9 | 901 | 37.0 |

| Worries me a little | 108 | 8.6 | 107 | 9.1 | 215 | 8.8 | |

| Worries me a lot | 572 | 45.7 | 744 | 63.0 | 1316 | 54.1 | |

| Fear of dying | Does not worry me | 376 | 30.1 | 372 | 31.5 | 748 | 30.8 |

| Worries me a little | 162 | 12.9 | 136 | 11.5 | 298 | 12.3 | |

| Worries me a lot | 713 | 57.0 | 673 | 57.0 | 1386 | 57.0 | |

| Fear of shortage of food and basic items caused by the pandemic | Does not worry me | 508 | 40.6 | 431 | 36.5 | 939 | 38.6 |

| Worries me a little | 240 | 19.2 | 215 | 18.2 | 455 | 18.7 | |

| Worries me a lot | 503 | 40.2 | 535 | 45.3 | 1038 | 42.7 | |

| Concern | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below the Median (≤22) | Above the Median (>22) | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Age (years) | 18 to 39 | 445 | 45.5 | 512 | 53.5 | 2.89 | 2.30 | 3.63 | <0.001 |

| 40 to 59 | 504 | 53.7 | 434 | 46.3 | 2.16 | 1.72 | 2.72 | <0.001 | |

| ≥60 | 379 | 51.5 | 151 | 28.5 | 1 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 788 | 50.7 | 767 | 49.3 | 1.60 | 1.35 | 1.89 | <0.001 |

| Male | 544 | 62.1 | 332 | 37.9 | 1 | ||||

| Income (minimum wage) | <1 | 712 | 61.3 | 450 | 38.7 | 2.49 | 1.78 | 3.48 | <0.001 |

| 1 to 3 | 416 | 47.8 | 454 | 52.2 | 1.73 | 1.45 | 2.06 | <0.001 | |

| ≥3 | 63 | 38.9 | 99 | 61.1 | 1 | ||||

| Skin color | Black and mixed race | 309 | 45.3 | 373 | 54.7 | 1.67 | 1.40 | 1.99 | <0.001 |

| White | 986 | 58.1 | 712 | 41.9 | 1 | ||||

| Educational level | Illiterate | 15 | 93.8 | 1 | 6.2 | 1 | 0.45 | 3.35 | 0.67 |

| Up to elementary school | 336 | 81.8 | 75 | 18.2 | 1.37 | 1.09 | 1.73 | 0.006 | |

| Up to high school | 713 | 75.1 | 237 | 24.9 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 1.99 | <0.001 | |

| Complete higher education/Postgraduation | 744 | 81.8 | 165 | 18.2 | 1 | ||||

| Did your routine change? | Not going out or going to the market, pharmacy, emergency | 875 | 57.7 | 642 | 42.3 | 1.38 | 0.85 | 2.25 | 0.19 |

| Going out to work | 408 | 48.6 | 431 | 51.4 | 1.99 | 1.21 | 3.26 | 0.006 | |

| No change in routine | 49 | 65.3 | 26 | 34.7 | 1 | ||||

| Did you adhere to prevention guidelines? | Yes | 1128 | 54.9 | 925 | 45.1 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.20 | 0.72 |

| No | 204 | 54.0 | 174 | 46.0 | 1 | ||||

| Did you adhere to isolation? | Yes | 991 | 57.3 | 737 | 42.7 | 1.43 | 1.20 | 1.71 | <0.001 |

| No | 340 | 48.4 | 362 | 51.6 | 1.00 | ||||

| Was your income affected? | No longer having income | 19 | 33.9 | 37 | 66.1 | 3.34 | 1.89 | 5.87 | <0.001 |

| Decreased a little | 556 | 47.2 | 622 | 52.8 | 1.92 | 1.62 | 2.26 | <0.001 | |

| Continues the same | 721 | 63.1 | 421 | 36.9 | 1 | ||||

| Were you unemployed? | Yes | 94 | 37 | 160 | 63.0 | 2.24 | 1.716 | 2.935 | <0.001 |

| No | 1238 | 56.9 | 939 | 43.1 | 1 | ||||

| Did you have any symptom? | Yes | 210 | 47.8 | 229 | 52.2 | 1.40 | 1.14 | 1.73 | 0.001 |

| No | 1122 | 56.3 | 870 | 43.7 | 1 | ||||

| Did a family member have any symptom? | Yes | 173 | 49.4 | 11 | 50.6 | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.61 | 0.03 |

| No | 1159 | 55.7 | 922 | 44.3 | 1 | ||||

| Did any family member test positive for COVID-19? | Yes | 1106 | 55.8 | 875 | 44.2 | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.54 | 0.03 |

| No | 226 | 50.2 | 224 | 49.8 | 1 | ||||

| Did you lose a family member? | Yes | 73 | 58.9 | 51 | 41.1 | 1.19 | 0.82 | 1.72 | 0.35 |

| No | 1259 | 545.6 | 45.4 | 1 | |||||

| COVID-19 test | Positive | 1120 | 55.7 | 889 | 44.3 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.54 | 0.04 |

| Negative | 212 | 50.2 | 210 | 49.8 | 1 | ||||

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 1.42 | 1.18–1.71 | 0.003 |

| Male | 1 | |||

| Skin color | Black and mixed race | 1.40 | 1.15–1.71 | <0.01 |

| White | 1 | |||

| Income (minimum wage) | <1 | 2.58 | 1.80–3.70 | <0.01 |

| 1 to 3 | 1.64 | 1.35–1.98 | <0.01 | |

| ≥3 | 1 | |||

| Age (years) | 18 to 39 | 3.07 | 2.39–3.94 | <0.01 |

| 40 to 59 | 2.42 | 1.89–3.10 | <0.01 | |

| ≥60 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbosa, A.P.; Batista, M.J. Perception of Concern and Associated Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Epidemiological Survey in a Brazilian Municipality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081293

Barbosa AP, Batista MJ. Perception of Concern and Associated Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Epidemiological Survey in a Brazilian Municipality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081293

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbosa, Adriano Pires, and Marília Jesus Batista. 2025. "Perception of Concern and Associated Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Epidemiological Survey in a Brazilian Municipality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081293

APA StyleBarbosa, A. P., & Batista, M. J. (2025). Perception of Concern and Associated Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Epidemiological Survey in a Brazilian Municipality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081293