A Gamified Digital Mental Health Intervention Across Six Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of a Large-Scale Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Aim 1: Assess the reach, feasibility, and acceptability of the intervention (i.e., the digital game) by country and user demographics;

- Aim 2: Assess knowledge of mental health topics among users based on responses during users’ engagement with the intervention.

2. Methods

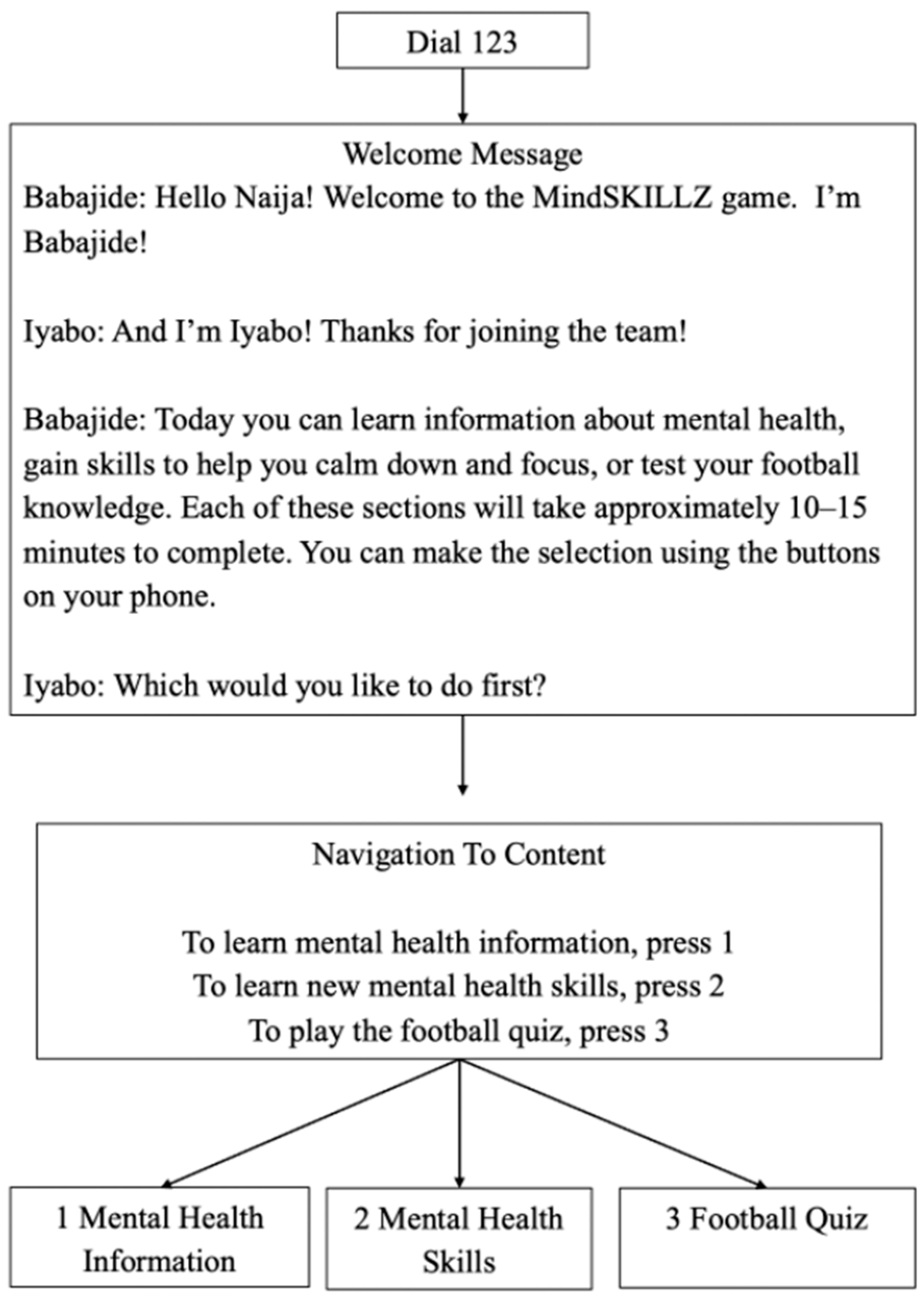

2.1. Digital Intervention Overview

2.2. Intervention Development

- Step 1: Logic Model, Storyboard, and Scripts. The foundation of the Digital MindSKILLZ intervention was established through a structured logic model and scripted content. The logic model defined the intervention’s intended outcomes, including improved mental health knowledge, awareness of coping skills, and reduced stigma around mental health. The storyboard provided a visual representation of the user journey, mapping the flow of the intervention and key decision points. Finally, GRS drafted scripts that a group of “Coaches” (near-peer lay mental health providers) reviewed for cultural relevance and age-appropriateness.

- Step 2: Preliminary Audio-Recording and Youth Engagement. Once the scripts were finalized, preliminary voice recordings were produced using youth voice actors. A pilot evaluation of the draft intervention was conducted with young people in Lagos, Nigeria [40]. Participants (n = 25) played the intervention and then participated in focus group discussions to evaluate the content’s clarity, relevance, and impact. The pilot results informed key revisions, particularly in ensuring that mental health concepts were clearly defined and relatable, and including a broader range of mental health topics.

- Step 3: Refinement and Re-Recording. Based on user feedback, the intervention underwent content refinement. Additional mental health information and coping strategies were incorporated, including explanations of the differences between mental health and mental illness. The soccer quiz was expanded to include internationally relevant questions. Following these updates, the scripts were re-recorded to enhance clarity and engagement.

- Step 4: Contextualization and Translation. The Digital MindSKILLZ intervention was adapted for each country where it was implemented, including local Viamo teams that reviewed the content and facilitated translations into local languages. To further improve appropriateness, youth voice actors from each country recorded the localized versions.

2.3. Platform Promotion and User Onboarding

2.4. Evaluation Design

- Feasibility: The extent to which Digital MindSKILLZ can be successfully implemented across countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Acceptability: The perception that Digital MindSKILLZ is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory.

2.5. Measures

- Demographics: We measured participants’ age using the following age categories: under 18, 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45 years and above. We measured gender (female or male), language, and geographic location using county and sub-county information as captured by mobile metadata or self-report. Geographic data, collected as Counties or Districts, were categorized as either urban or rural based on publicly available information.

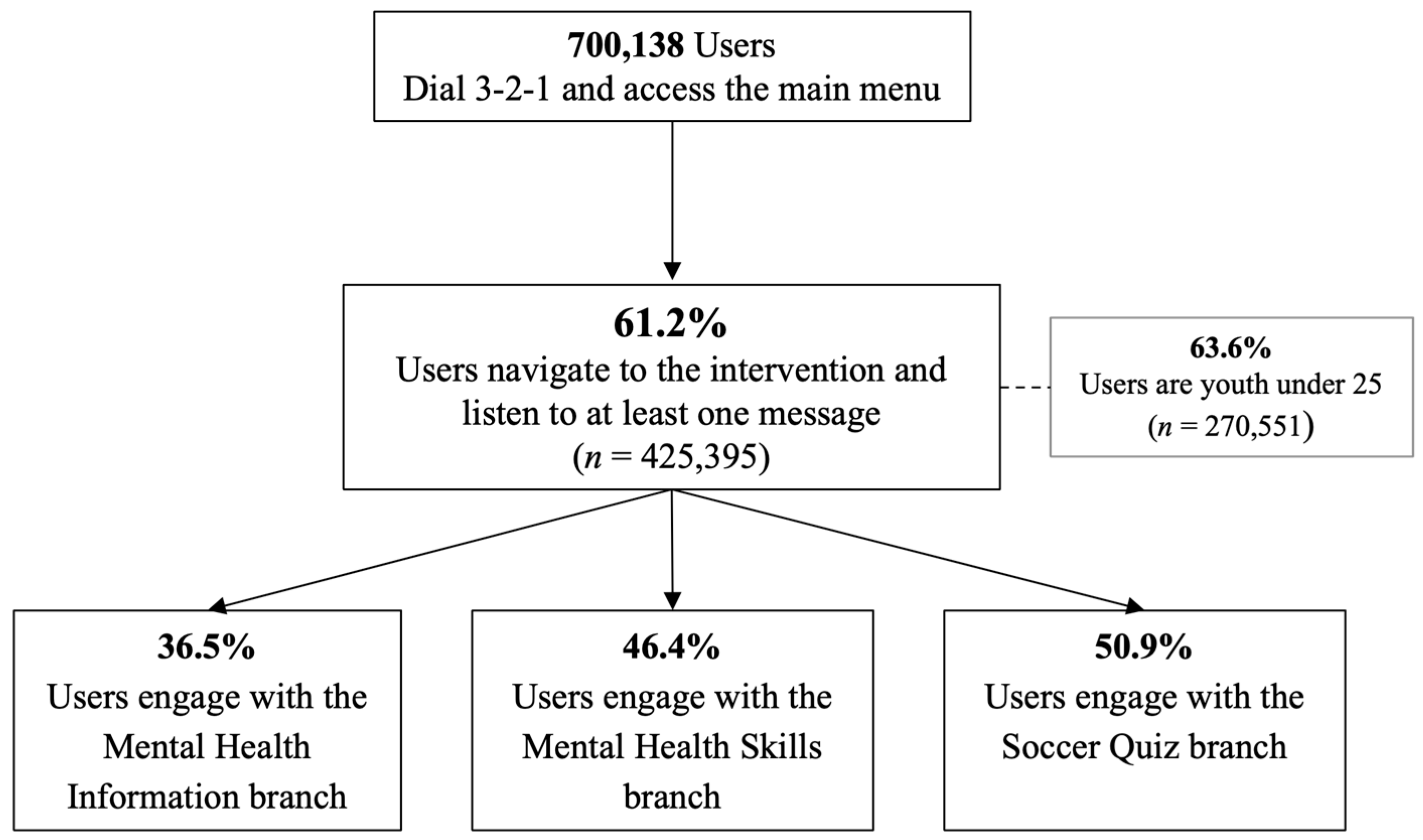

- Reach: We measured the number of callers who dialed the platform and reached the main menu and the number of unique users—i.e., the number of individuals who accessed at least one voice recording during the intervention.

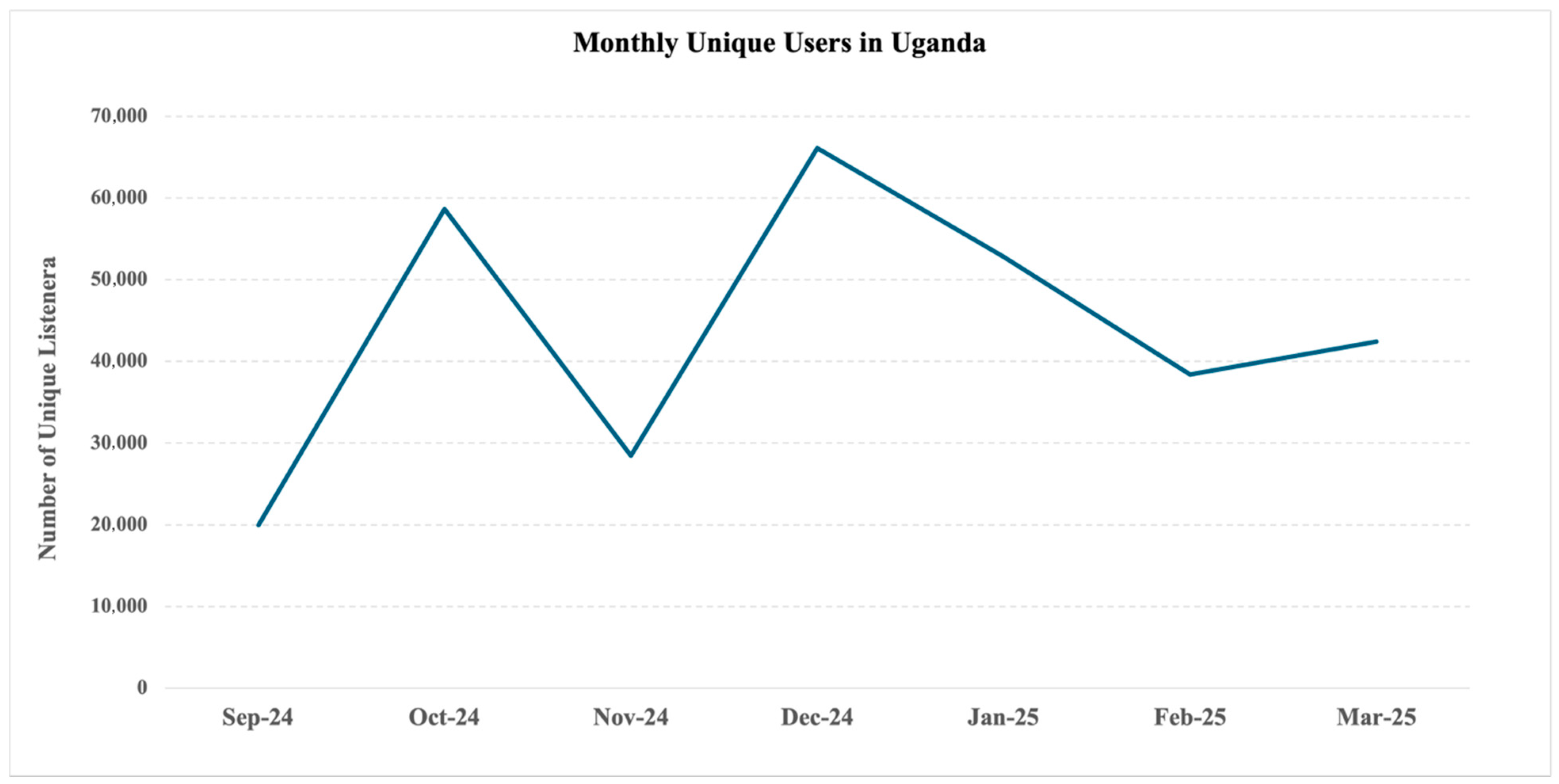

- Feasibility: We examined participant engagement as the average number of voice recordings accessed by each unique user. We also measured the number of unique users per full calendar month, disaggregated by country. We measured adherence as the number and proportion of messages completed in each of the three branches of the intervention (i.e., 18 messages in the information branch, 5 in the skills branch, and 11 in the soccer branch).

- Acceptability: We included three measures of acceptability: (1) comprehension: post-intervention user-reported understanding of the content, with three response options: “Understood all messages”, “Understood some messages”, and “Did not understand the messages”; (2) helpfulness: post-intervention user feedback on the most helpful aspect of the intervention, with the three response options: “Mental health information”, “Mental health skills”, and “Soccer quiz”; and (3) overall satisfaction: post-intervention rating of likelihood to recommend the intervention to a friend, with three response options: “Very likely”, “Not sure”, and “Very unlikely.”

- Mental health knowledge: We measured mental health knowledge based on users’ responses to 18 true-or-false statements embedded within the mental health information branch of the intervention. The statements were developed by GRS to align with the intervention’s content and objectives.

2.6. Data Collection Procedures

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Reach

3.2. Feasibility

3.3. Participant Engagement with Different Content Areas (Branches)

3.4. Acceptability

3.5. Mental Health Knowledge

4. Discussion

- Adapt Content and Delivery to Country-Specific Realities. Participant engagement varied by country, highlighting the need for tailored content and clarification about the factors contributing to these differences. Adapting the intervention’s content and implementation strategies for each setting, including language, voice actors, and examples, may enhance the intervention’s reach [53].

- Address the Digital Gender Gap. Overall, gender distribution among users was balanced (45.9% female), but gender disparities existed in some countries, most notably the DRC, where only 22% of users were female. These disparities align with regional trends, where females may face social and economic barriers to mobile ownership and access to digital tools [54,55]. However, Rwanda stands out as an example of how targeted strategies can promote more equitable access. On the Rwandan platform, 66% of users were female, a shift driven by deliberate efforts to prioritize women and girls, including gender-focused content, partnerships with women’s organizations, and tailored promotion strategies. Rwanda also benefits from higher mobile penetration among women and near-national platform coverage, which further facilitates equitable access. These results suggest that addressing the digital gender gap is not only feasible but essential for expanding reach. Future implementations should consider gender-inclusive approaches, including co-design with women’s groups, female-centric promotion, and ongoing monitoring of gendered engagement patterns.

- 3.

- Optimize Onboarding to Improve Early Engagement and Adherence. Drop-off rates (i.e., call but do not listen to a voice recording) ranged from 34% to 69% across countries, underscoring the need for further investigation into user expectations, onboarding processes, and early-stage intervention design [25,49,56]. Enhancing the onboarding experience may boost the feasibility of the intervention. Conducting A/B testing is recommended to compare the current branching experience with a simplified linear model. Clarifying the intervention’s purpose and starting with engaging content has also been shown to retain users’ attention and reduce attrition, and should be incorporated into future onboarding strategies [48].

- 4.

- Develop Models for Long-Term Engagement. Monthly users showed steady declines over time, with Uganda being a notable exception. Sustained engagement of DMHIs hinges on maintaining user engagement beyond initial exposure, and sustained engagement strategies, such as periodic promotion, content updates, or integration with other platforms or initiatives, should be explored.

- 5.

- Ensure Entertainment is a Bridge to Learning. User preferences suggest the soccer quiz was a key entry point, with more users engaging with it than with the mental health content. The soccer quiz and voice-activated feedback (e.g., “Goal!” or “Nice try!”) were intentionally designed as gamified elements to support user engagement. However, our findings highlight the need to ensure these mechanics function as bridges to health content rather than distractions. Future iterations should ensure that gamified components are meaningfully integrated with essential mental health messages.

- 6.

- Use Validated Mental Health Measures Embedded in the Intervention. Correct responses to the 18 true/false items ranged widely, revealing possible knowledge gaps in critical mental health concepts among the intervention’s mostly young and rural users, a group typically underrepresented in mental health research [57,58]. However, future iterations must incorporate psychometrically validated measures (e.g., Mental Health Literacy Scale) to ensure accurate, reliable, and culturally appropriate measures of mental health outcomes.

- 7.

- Plan Future Studies of Intervention Effectiveness and Implementation. Building on the results from this evaluation, a future evaluation of this intervention should use a mixed-methods and longitudinal approach to capture effectiveness and implementation outcomes. It should also draw on a determinants implementation science framework to explore barriers and facilitators to implementation, which was beyond the scope of this evaluation. Qualitative insights are required to explore many unanswered questions about user experiences and behaviors. Future evaluations should also include pre–post assessments with control or comparison groups and long-term follow-up. A pilot randomized controlled trial is tentatively planned in Malawi and will offer an opportunity to advance this work.

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMHI | Digital Mental Health Intervention |

| GRS | Grassroot Soccer |

| IVR | Interactive Voice Response |

| LMIC | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MHL | Mental Health Literacy |

| MNO | Mobile Network Operator |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

References

- Hart, C.; Norris, S.A. Adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa: Crisis? What crisis? Solution? What solution? Glob. Health Action 2024, 17, 2437883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jörns-Presentati, A.; Napp, A.-K.; Dessauvagie, A.S.; Stein, D.J.; Jonker, D.; Breet, E.; Charles, W.; Swart, R.L.; Lahti, M.; Suliman, S.; et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; de Pablo, G.S.; Shin, J., II; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas, P.J.; Davey, C.G.; Mehta, U.M.; Shah, J.; Torous, J.; Allen, N.B.; Avenevoli, S.; Bella-Awusah, T.; Chanen, A.; Chen, E.Y.H.; et al. Towards a youth mental health paradigm: A perspective and roadmap. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3171–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodi, T.; Quarshie, E.N.-B.; Oppong Asante, K.; Radzilani-Makatu, M.; Makgahlela, M.; Nkoana, S.; Mutambara, J. Mental health literacy of school-going adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A regional systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Torok, M.; McCallum, S. Help-seeking attitudes and intentions for generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents: The role of anxiety literacy and stigma. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A.W.T.; Lam, L.C.W.; Chan, S.S.M.; Lee, S. Knowledge of mental health symptoms and help seeking attitude in a population-based sample in Hong Kong. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Von Sternberg, K.; Davis, K. The impact of mental health literacy, stigma, and social support on attitudes toward mental health help-seeking. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2017, 19, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindow, J.C.; Hughes, J.L.; South, C.; Minhajuddin, A.; Gutierrez, L.; Bannister, E.; Trivedi, M.H.; Byerly, M.J. The Youth Aware of Mental Health Intervention: Impact on Help Seeking, Mental Health Knowledge, and Stigma in U.S. Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadgarinejad, A.; Nazarihermoshi, N.; Hematichegeni, N.; Jazaiery, M.; Yousefishad, S.; Mohammadian, H.; Sayyah, M.; Dastoorpoor, M.; Cheraghi, M. Relationship between health literacy and generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Khuzestan province, Iran. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1294562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Cui, Y.; Xia, Z.; Hu, J.; Xue, Y.; Huang, X.; Wan, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhang, S. Association between health literacy, depressive symptoms, and suicide-related outcomes in adolescents: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; Evdoka-Burton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, R.; Li, D.; Wan, Y.; Tao, F.; Fang, J. Association of health literacy and sleep problems with mental health of Chinese students in combined junior and senior high school. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, R.; Patalay, P.; Humphrey, N. A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and measurement of mental health literacy in adolescent research: Current challenges and inconsistencies. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freţian, A.M.; Graf, P.; Kirchhoff, S.; Glinphratum, G.; Bollweg, T.M.; Sauzet, O.; Bauer, U. The Long-Term Effectiveness of Interventions Addressing Mental Health Literacy and Stigma of Mental Illness in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, L.; Pedley, R.; Johnson, I.; Bell, V.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Brooks, H. Mental health literacy in children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A mixed studies systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 961–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Saraceno, B.; Granstein, J. Scaling up mental health care in resource-poor settings. In Improving Mental Health Care; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, M.L.; Scorza, P.; Shultz, J.M.; Helpman, L.; Mootz, J.J.; Johnson, K.A.; Neria, Y.; Bradford, J.-M.E.; Oquendo, M.A.; Arbuckle, M.R. Challenges and Opportunities in Global Mental Health: A Research-to-Practice Perspective. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, C.; Sukums, F.; Radovanovic, D.; Ngowi, B.; Noll, J.; Winkler, A.S. Sub-Saharan Africa—The new breeding ground for global digital health. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e160–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G.; Reich, S.M.; Liaw, N.A.; Chia, E.Y.M. The Effect of Digital Mental Health Literacy Interventions on Mental Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e51268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Zin, S.T.P.; Chestnov, R.; Novak, A.M.; Lev-Ari, S.; Snyder, M. Mental Health for All: The Case for Investing in Digital Mental Health to Improve Global Outcomes, Access, and Innovation in Low-Resource Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebel, C.; Gabbay, M.; Shrestha, N.; Saldarriaga, G.; Reilly, S.; White, R.; Liu, G.; Allen, D.; Zuluaga, M.I. Community-based mental health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative study with international experts. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghouts, J.; Eikey, E.; Mark, G.; De Leon, C.; Schueller, S.M.; Schneider, M.; Stadnick, N.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D.; Sorkin, D.H. Barriers to and Facilitators of User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtimaki, S.; Martic, J.; Wahl, B.; Foster, K.T.; Schwalbe, N. Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e25847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Global Smartphone Penetration Rate as Share of Population from 2016 to 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/203734/global-smartphone-penetration-per-capita-since-2005/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- International Telecommunication Union. Global Connectivity Report 2022; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, S.; Millington, C.; Cheers, D.; Boydell, K.; Schubert, E.; Meade, T.; Nguyen, Q.V. What Works and What Doesn’t Work? A Systematic Review of Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Young People. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Panahi, S.; Sayarifard, A.; Ashouri, A. Identifying the prerequisites, facilitators, and barriers in improving adolescents’ mental health literacy interventions: A systematic review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.; Blair, L.; Mesch, R. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction Fieldbook, 2014; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cugelman, B. Gamification: What It Is and Why It Matters to Digital Health Behavior Change Developers. JMIR Serious Games 2013, 1, e3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hew, K.F.; Du, J. Gamification enhances student intrinsic motivation, perceptions of autonomy and relatedness, but minimal impact on competency: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2024, 72, 765–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.S.; Friedrich, G.K.; Ndlovu, M.; Neilands, T.B.; McFarland, W. An adolescent-targeted HIV prevention project using African professional soccer players as role models and educators in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Aids Behav. 2006, 10 (Suppl. 4), 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Z.A.; DeCelles, J.; Bhauti, K.; Hershow, R.B.; Weiss, H.A.; Chaibva, C.; Moyo, N.; Mantula, F.; Hatzold, K.; Ross, D.A. A Sport-Based Intervention to Increase Uptake of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Among Adolescent Male Students: Results From the MCUTS 2 Cluster-Randomized Trial in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. JAIDS—J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 72, S292–S298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrill, K.G.; Merrill, J.C.; Hershow, R.B.; Barkley, C.; Rakosa, B.; DeCelles, J.; Harrison, A. Linking at-risk South African girls to sexual violence and reproductive health services: A mixed-methods assessment of a soccer-based HIV prevention program and pilot SMS campaign. Eval. Program Plann. 2018, 70, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, U.U.; Ja’afar, I.K. Mental health literacy among young people in Africa: A keystone for social development. Glob. Health Econ. Sustain. 2025, 025110021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Youth-Centred Digital Health Interventions: A Framework for Planning, Developing and Implementing Solutions with and for Young People; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, P.; Lee, D.; Kuthyola, K.; Odusolu, B.; Sekoni, A. Pilot Evaluation of Digital MindSKILLZ in Lagos, Nigeria: An Interactive Voice Response Game to Improve Mental Wellbeing of Adolescents 2024. Available online: https://ve-ame.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/1_Abstract_Ndlovu_b6637f94d8.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Harden, S.M.; Gaglio, B.; Rabin, B.; Smith, M.L.; Porter, G.C.; Ory, M.G.; Estabrooks, P.A. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindu, T.; Mutero, I.T.; Ngcobo, W.B.; Musesengwa, R.; Chimbari, M.J. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Young People in Rural South Africa: Prospects and Challenges for Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.; Bavin, L.; Lucassen, M.; Stasiak, K.; Hopkins, S.; Merry, S. Beyond the Trial: Systematic Review of Real-World Uptake and Engagement with Digital Self-Help Interventions for Depression, Low Mood, or Anxiety. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, G.D.; Speckemeier, C.; Abels, C.; Plescher, F.; Börchers, K.; Wasem, J.; Blasé, N.; Neusser, S. Problems and Barriers Related to the Use of Digital Health Applications: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumel, A.; Muench, F.; Edan, S.; Kane, J.M. Objective User Engagement With Mental Health Apps: Systematic Search and Panel-Based Usage Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Nicholas, J.; Larsen, M.E.; Firth, J.; Christensen, H. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: Evidence, theory and improvements. BMJ Ment. Health 2018, 21, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipschitz, J.M.; Pike, C.K.; Hogan, T.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Burdick, K.E. The engagement problem: A review of engagement with digital mental health interventions and recommendations for a path forward. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2023, 10, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Lewis, C.C.; Stanick, C.; Powell, B.J.; Dorsey, C.N.; Clary, A.S.; Boynton, M.H.; Halko, H. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittas, V.; Daniore, P.; Chavez, S.J.; Wray, T.B. Challenges in implementing cultural adaptations of digital health interventions. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GSMA. The Mobile Gender Gap Report; GSMA: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez-Sánchez, I.C.; Glasserman-Morales, L.D. Gender Digital Divide and Women’s Digital Inclusion: A Systematic Mapping. Multidiscip. J. Gend. Stud. 2023, 12, 258–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Opra Widerquist, M.A.; Lowery, J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perowne, R.; Rowe, S.; Gutman, L.M. Understanding and Defining Young People’s Involvement and Under-Representation in Mental Health Research: A Delphi Study. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warraitch, A.; Wacker, C.; Bruce, D.; Bourke, A.; Hadfield, K. A rapid review of guidelines on the involvement of adolescents in health research. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Mobile Network Operator (MNO) | Intervention Language Availability | Launch Date | Number of Days Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRC | Vodacom | Lingala | 7 February 2025 | 46 |

| Ghana | Vodafone | Twi | 25 September 2024 | 176 |

| Nigeria | Airtel | Pidgin, Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo | 19 September 2024 | 182 |

| Rwanda | MTN | Kinyarwanda | 13 September 2024 | 188 |

| Uganda | Airtel | Luganda | 25 September 2024 | 176 |

| Zambia | MTN | Bemba | 7 October 2024 | 164 |

| Country | Unique Users | Unique Users (Percent of Total) | Female | Under 25 | Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRC | 22,632 | 5.3% | 22.4% | 74.2% | 76.8% |

| Ghana | 950 | 0.2% | 43.9% | 71.7% | NA |

| Nigeria | 76,282 | 17.9% | 43.8% | 68.4% | 72.0% |

| Rwanda | 63,654 | 15.0% | 65.8% | 80.4% | 82.4% |

| Uganda | 248,713 | 58.5% | 41.7% | 55.7% | 62.6% |

| Zambia | 13,164 | 3.1% | 58.1% | 70.2% | 75.6% |

| Total/a Mean | 425,395 | 100% | 46.4% | 63.6% | 68.3% |

| # | Category and Items | * Percent Correct |

|---|---|---|

| Me and My Mental Health | 50% | |

| 1 | Having “good mental health” means being happy all the time. | 21% |

| 2 | There are treatments for mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. | 75% |

| 3 | Everyone deserves support and understanding, even if their culture views mental health differently. | 80% |

| 4 | Keeping your feelings inside helps others understand how you feel. | 36% |

| 5 | When I experience strong emotions, they control me; there’s nothing I can do to calm down. | 42% |

| Keeping Good Mental Health | 76% | |

| 6 | Stress is normal, but too much stress harms our minds and bodies. | 83% |

| 7 | Getting enough sleep is one of the best things we can do for good mental health. | 89% |

| 8 | Social media can also be a mental health risk. | 82% |

| 9 | A healthy diet means eating meat at every meal. | 35% |

| 10 | Setting goals and making plans to achieve them helps us grow into the people we want to be. | 92% |

| Know The Facts | 56% | |

| 11 | People with mental health problems are weak. | 34% |

| 12 | Mental health stigma can prevent people from seeking help. | 66% |

| 13 | Negative peer pressure can make it hard to say no to drugs and alcohol. | 74% |

| 14 | Feeling sad means you have depression. | 23% |

| 15 | People experiencing anxiety may have different symptoms. | 85% |

| Getting Support | 65% | |

| 16 | When a friend asks for help with a mental health problem, listening carefully is a great first step. | 93% |

| 17 | There are mental health services available to you. | 85% |

| 18 | You are a young person, so your privacy is not important. | 17% |

| Overall Correct | 62% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barkley, C.K.; Nyakonda, C.N.; Kuthyola, K.; Ndlovu, P.; Lee, D.; Dallos, A.; Kofi-Armah, D.; Obeng, P.; Merrill, K.G. A Gamified Digital Mental Health Intervention Across Six Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of a Large-Scale Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081281

Barkley CK, Nyakonda CN, Kuthyola K, Ndlovu P, Lee D, Dallos A, Kofi-Armah D, Obeng P, Merrill KG. A Gamified Digital Mental Health Intervention Across Six Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of a Large-Scale Implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081281

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarkley, Christopher K., Charmaine N. Nyakonda, Kondwani Kuthyola, Polite Ndlovu, Devyn Lee, Andrew Dallos, Danny Kofi-Armah, Priscilla Obeng, and Katherine G. Merrill. 2025. "A Gamified Digital Mental Health Intervention Across Six Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of a Large-Scale Implementation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081281

APA StyleBarkley, C. K., Nyakonda, C. N., Kuthyola, K., Ndlovu, P., Lee, D., Dallos, A., Kofi-Armah, D., Obeng, P., & Merrill, K. G. (2025). A Gamified Digital Mental Health Intervention Across Six Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Cross-Sectional Evaluation of a Large-Scale Implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081281