Maternal Satisfaction with Perinatal Care and Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications of Study Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younger-Meek, J.; Noble, L. Technical report: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding: Report of the Expert Consultation. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/WHO_NHD_01.09/en/index.html (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINCTM) Survey. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/mpinc/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc/index.htm (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Benefits Both Baby and Mom. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/features/breastfeeding-benefits.html (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Pathirana, M.M.; Andraweera, P.H.; Aldridge, E.; Harrison, M.; Harrison, J.; Leemaqz, S.; Arstall, M.A.; Dekker, G.A.; Roberts, C.T. The association of breast feeding for at least six months with hemodynamic and metabolic health of women and their children aged three years: An observational cohort study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Continued Breastfeeding for Healthy Growth and Development. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/continued-breastfeeding (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization. Strengthening Maternal and Child Health Through Improved Breastfeeding Practices. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/15-6-2025-strengthening-maternal-and-child-health-through-improved-breastfeeding-practices (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Goldstein, I.; Sadaka, Y.; Amit, G.; Kasir, N.; Bourgeron, T.; Warrier, V.; Akiva, P.; Tsadok, M.A.; Zimmerman, D.R. Breastfeeding duration and child development. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e251540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, C.M.; Felice, J.P.; O’Sullivan, E.; Rasmussen, K.M. Breastfeeding and health outcomes for the mother-infant dyad. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.E.; Faux, S. Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Report Card United States. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/media/pdfs/2024/05/2020-breastfeeding-report-card-h.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Dabritz, H.A.; Hinton, B.G.; Babb, J. Maternal hospital experiences associated with breastfeeding at 6 months in a northern California county. J. Hum. Lact. 2010, 26, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Jones, L.; Feary, A.-M. The effects of single-family rooms on parenting behavior and maternal psychological factors. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliszewska, K.M.; Bidzan, M.; Świątkowska-Freund, M.; Preis, K. Socio-demographic and psychological determinants of exclusive breastfeeding after six months postpartum—a Polish case-cohort study. Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.K.; Ricketts, S.; Dellaport, J. Hospital practices that increase breastfeeding duration: Results from a population-based study. Birth 2007, 34, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waits, A.; Guo, C.-Y.; Chien, L.Y. Evaluation of factors contributing to the decline in exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum: The 2011–2016 National Surveys in Taiwan. Birth 2018, 45, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizon, A.M.B.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Women’s satisfaction with breastfeeding and risk of exclusive breastfeeding interruption. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.B.; Sclafani, V. Birth experiences, breastfeeding, and the mother–child relationship: Evidence from a large sample of mothers. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 54, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökbulut, N.; Beydağ, K.D. The effects of women’s satisfaction with their birth experience on breastfeeding sufficiency. SHS Web Conf. 2017, 37, 01083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarère, J.; Gelbert-Baudino, N.; Ayral, A.-S.; Duc, C.; Berchoud, V.; Schelstraete, C. Determinants of 6-month maternal satisfaction with breastfeeding experience in a multicenter prospective cohort study. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 28, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossano, C.; Townsend, K.; Walton, A.; Blomquist, J.; Handa, V. The maternal childbirth experience more than a decade after delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 342.e1–342.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinic, K. Understanding and promoting birth satisfaction in new mothers. MCN 2017, 42, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olza, I.; Leahy-Warren, P.; Benyamini, Y.; Kazmierczak, M.; Karlsdottir, S.I.; Spyridou, A.; Crespo-Mirasol, E.; Takacs, L.; Hall, P.J.; Murphy, M.; et al. Women’s psychological experiences of physiological childbirth: A meta-synthesis. BMJ Open 2018, 18, e020347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, F.; Nakamura, M.U.; Nomura, R.M.Y. Women’s satisfaction with childbirth in a public hospital in Brazil. Birth 2021, 48, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchard, E.R.; Rutherford, H.J.V.; Holmes, A.J.; Jamadar, S.D. Matrescence: Lifetime impact of motherhood on Cognition and the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 27, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehara, K.; Noguchi, M.; Shimane, T.; Misago, C. The positive psychological impact of rich childbirth experiences on child-rearing. Jpn. J. Public Health. 2009, 56, 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbort, J.G. Women’s lived experience of their unexpected birthing process. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2009, 34, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, M.H.; Van Hastenberg, E.; Van Dillen, J.; Van Pampus, M.G.; De Miranda, E.; Stramrood, C.A.I. Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women’s perceptions and views. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.F.; Andersson, E. The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: A systematic review. Midwifery 2016, 39, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Galea, L. Postpartum depression: Etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care. Horm. Behav. 2016, 77, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.; Dunn, D.M.; Njoroge, W.F. Impact of postpartum mental illness upon infant development. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinic, K. Predictors of breastfeeding confidence in the early postpartum period. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, D.; Zambri, F.; Govoni, L.; Ricchi, A.; Infante, R.; Palmieri, E.; Calli, M.C.; Molinazzi, M.T.; Messina, M.P.; Putignano, A.; et al. Breastfeeding promotion and support: A quality improvement study. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Di Sanità 2021, 57, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (WHO/UNICEF). Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breast-feeding: The Special Role of Maternity Services/a Joint WHO/UNICEF Statement. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39679 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Kellams, A.; Harrel, C.; Omage, S.; Gregory, C.; Rosen-Carole, C. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine ABM Clinical Protocol #3: Supplementary Feedings in the Healthy Term Breastfed Neonate, Revised 2017. Breastfeed. Med. 2017, 12, 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Radzyminski, S.; Callister, L.C. Health professionals’ attitudes and beliefs about breastfeeding. J. Perinat. Educ. 2015, 24, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, J.; Laidlaw, A. Perceptions of postnatal care: Factors associated with primiparous mother’s perceptions of postnatal communication and care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankumbi, J.; Mukama, A.A.; Ngabirano, T.D. Predictors of breastfeeding self-efficacy among women attending an urban postnatal clinic, Uganda. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzakpasu, S.; Kaczorowski, J.; Chalmers, B.; Heaman, M.; Duggan, J.; Neusy, E. The Canadian maternity experiences survey: Design and methods. J. Obstet.Gynaecol. Can. 2008, 30, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. 2008. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/injury-prevention/health-surveillance-epidemiology-division/maternal-infant-health/canadian-maternity-experiences-survey.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Agampodi, S.B.; Fernando, S.; Dharmaratne, S.D.; Agampodi, T.C. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding: Validity of retrospective assessment at nine months of age. BMC Pediatr. 2011, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, E.H.; Chen, J.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Perrine, C.G. Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding—United States, 2011–2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luegmair, K.; Zenzmaier, C.; Oblasser, C.; König-Bachmann, M. Women’s satisfaction with care at the birthplace in Austria: Evaluation of the Babies Born Better survey national dataset. Midwifery 2018, 59, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baby-Friendly USA. Available online: https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Lojander, J.; Axelin, A.; Bergman, P.; Niela-Vilén, H. Maternal perceptions of breastfeeding support in a birth hospital before and after designation to the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: A quasi-experimental study. Midwifery 2022, 110, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

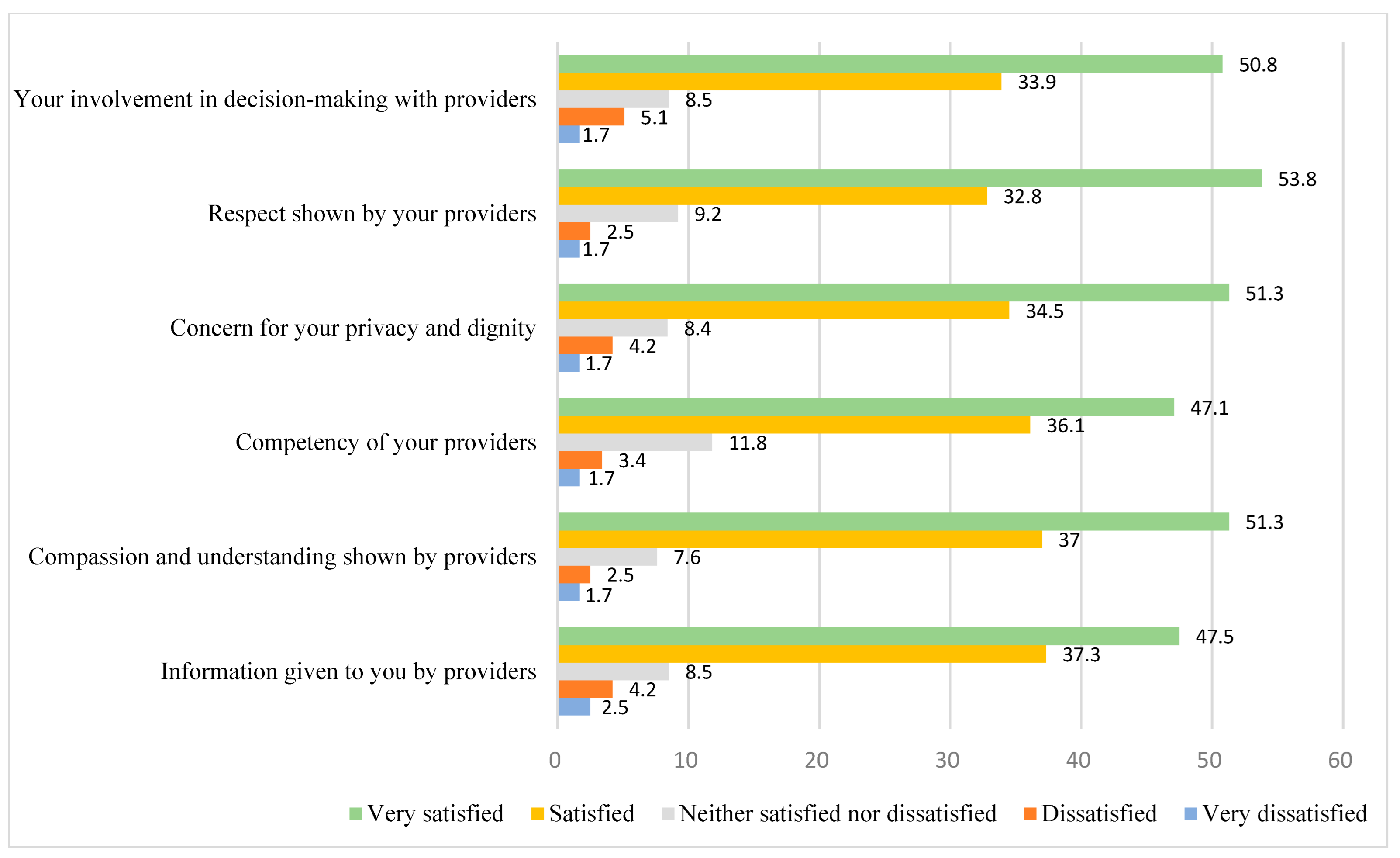

| Variables | M or % | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding (6 mo) | 25% | 0–1 | |

| Satisfaction with care scale | 25.73 | 4.91 | 6–30 |

| Satisfaction with: | |||

| Information provided by providers | 4.24 | 0.94 | 1–5 |

| Compassion shown by providers | 4.33 | 0.85 | 1–5 |

| Competency of providers | 4.25 | 0.89 | 1–5 |

| Concern for privacy/dignity | 4.28 | 0.94 | 1–5 |

| Respect shown by providers | 4.36 | 0.86 | 1–5 |

| Your involvement in decision-making | 4.27 | 0.94 | 1–5 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age | 25.67 | 0.37 | 16–38 |

| Economic hardship | 1.91 | 2.23 | 0–6 |

| Married | 28% | 0–1 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 40% | 0–1 | |

| Black | 28% | 0–1 | |

| Hispanic | 14% | 0–1 | |

| Native American | 17% | 0–1 | |

| Parity | 1.30 | 1.50 | 0–10 |

| Variables | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Perinatal Care | 1.19 (1.04—1.37) | * | 0.07 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age | 1.02 (0.92—1.13) | 0.05 | |

| Economic hardship | 0.88 (0.66—1.17) | 0.15 | |

| Married | 2.83 (0.99—8.09) | * | 0.54 |

| Race/ethnicity (White) | |||

| Black | 0.40 (0.11—1.49) | 0.67 | |

| Hispanic | 1.26 (0.30—5.34) | 0.74 | |

| Native American | 0.63 (0.14—2.80) | 0.76 | |

| Parity | 1.21 (0.87—1.67) | 0.17 | |

| Constant | 0.01 | ** | 2.38 |

| Nagelkerke R Square | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dressler, C.M.; Shreffler, K.M.; Wilhelm, I.R.; Price, J.R.; Gold, K.P. Maternal Satisfaction with Perinatal Care and Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081246

Dressler CM, Shreffler KM, Wilhelm IR, Price JR, Gold KP. Maternal Satisfaction with Perinatal Care and Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081246

Chicago/Turabian StyleDressler, Caitlin M., Karina M. Shreffler, Ingrid R. Wilhelm, Jameca R. Price, and Karen P. Gold. 2025. "Maternal Satisfaction with Perinatal Care and Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081246

APA StyleDressler, C. M., Shreffler, K. M., Wilhelm, I. R., Price, J. R., & Gold, K. P. (2025). Maternal Satisfaction with Perinatal Care and Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081246