Residential Outdoor Environments for Individuals with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Study Approach

3. Results

3.1. Outdoor Areas’ Needs and Expectations

3.1.1. Outdoor Environmental Triggers

3.1.2. Outdoor Space Layout

3.2. Design Principles

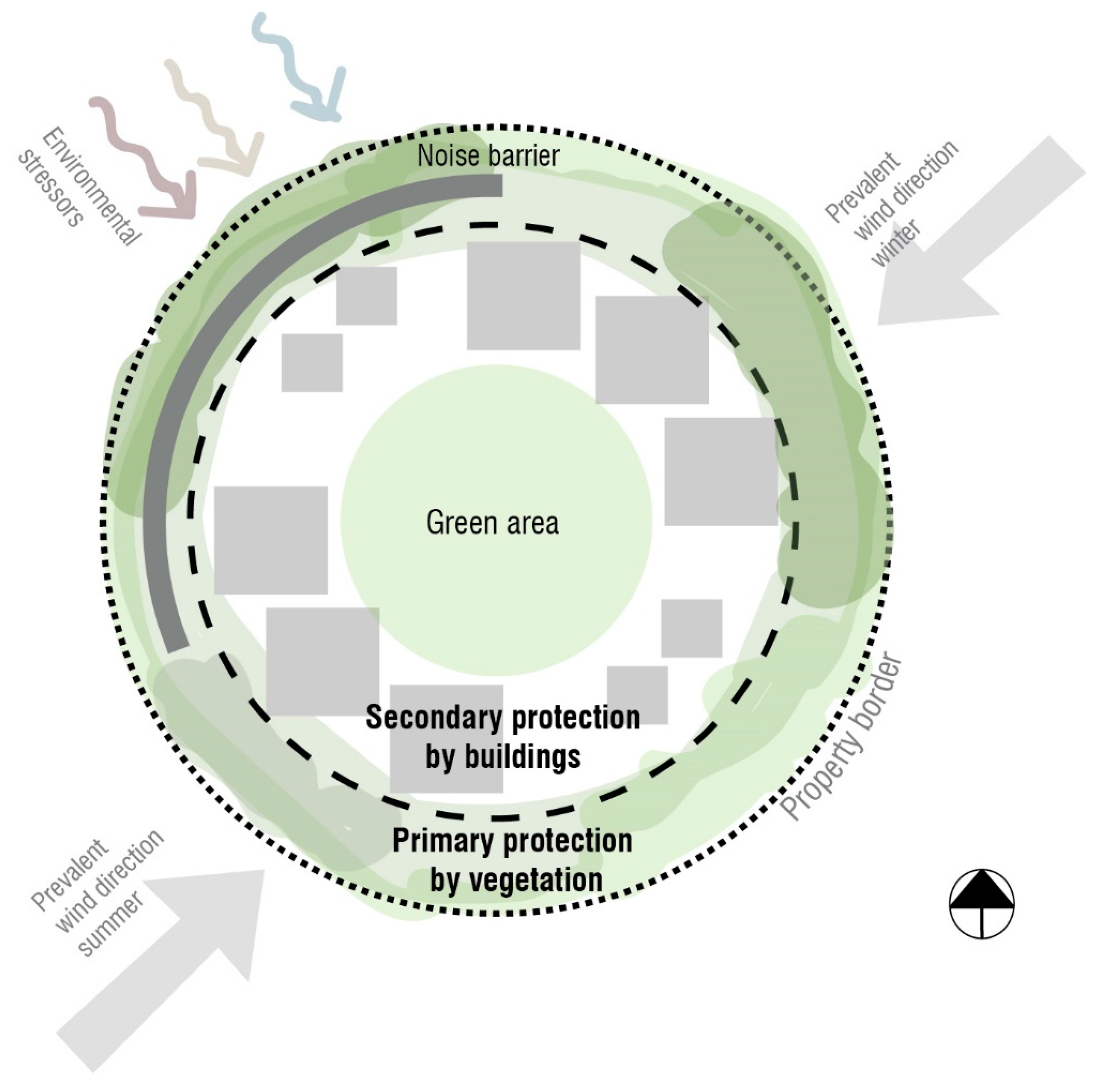

3.2.1. Principle of Protective Layers

3.2.2. Zoning Principles

| Zoning of the Area from Inside out | ||||

| Private | Semi-Private | Semi-Public | Edge Planting (Protective Layer) | |

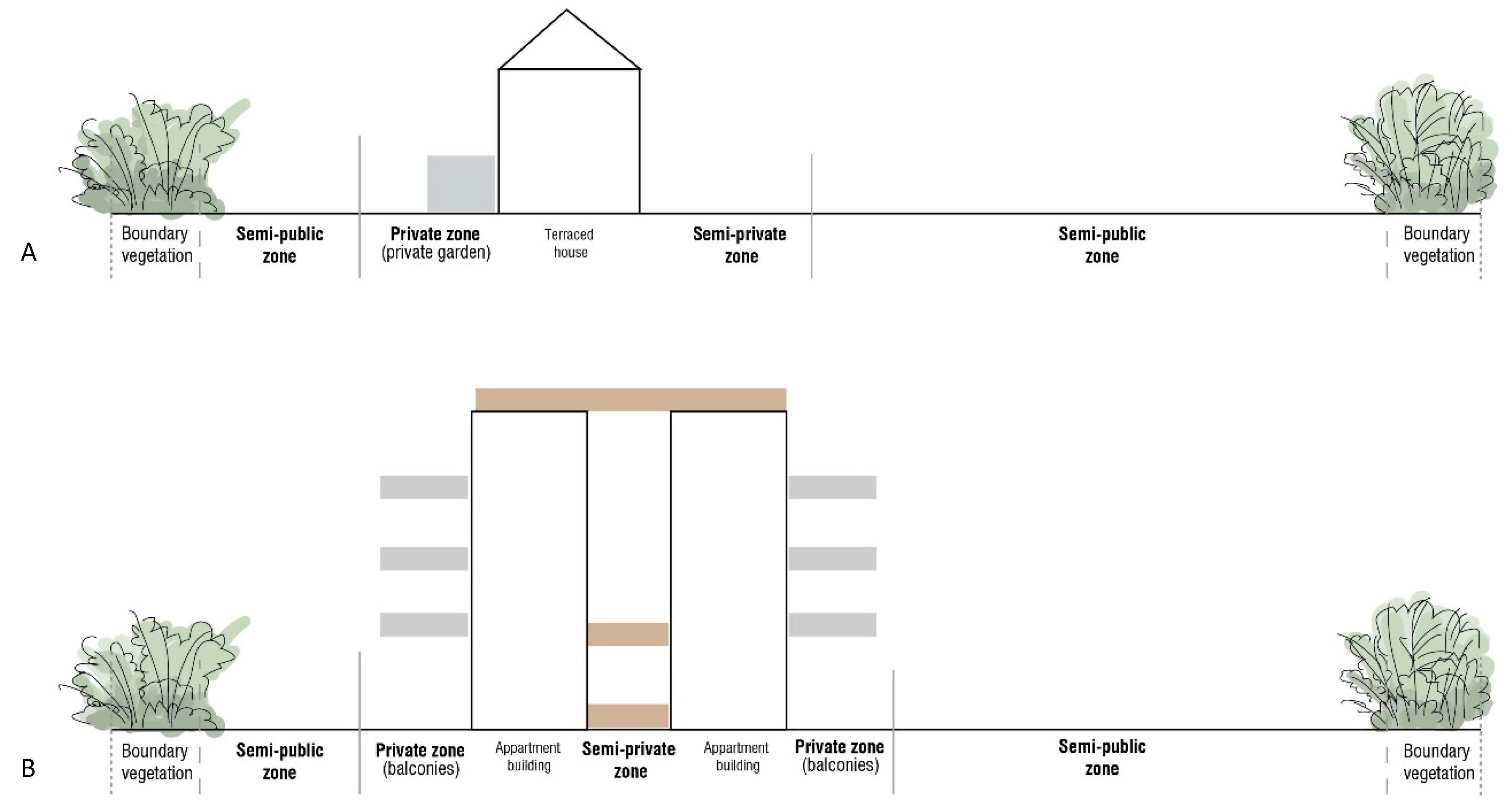

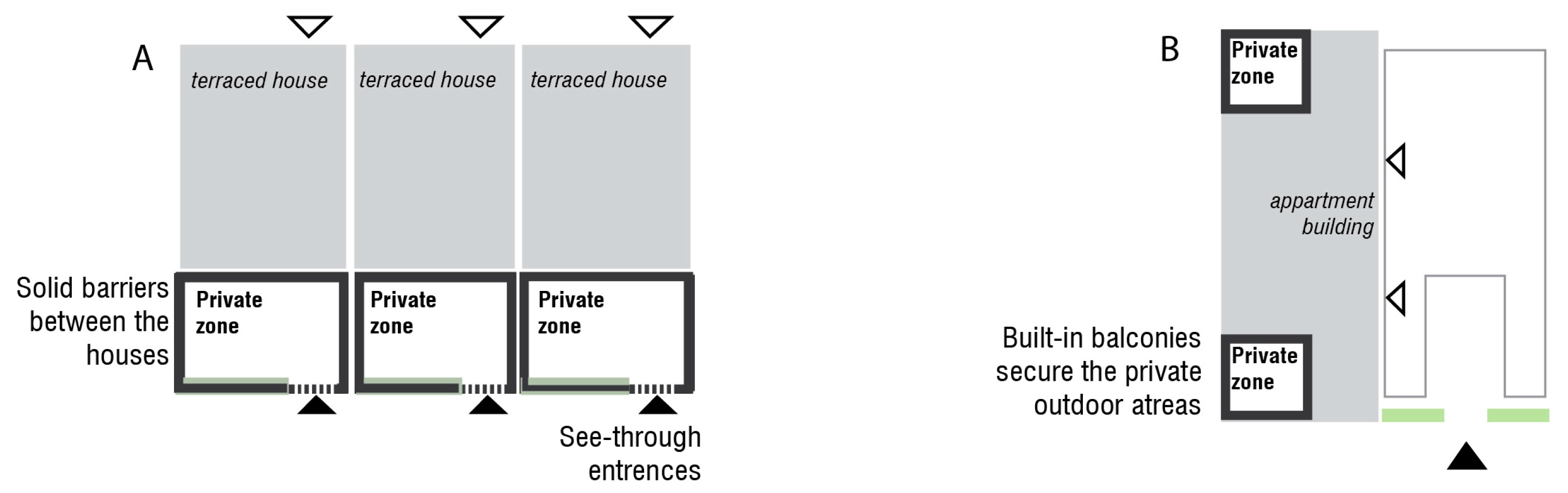

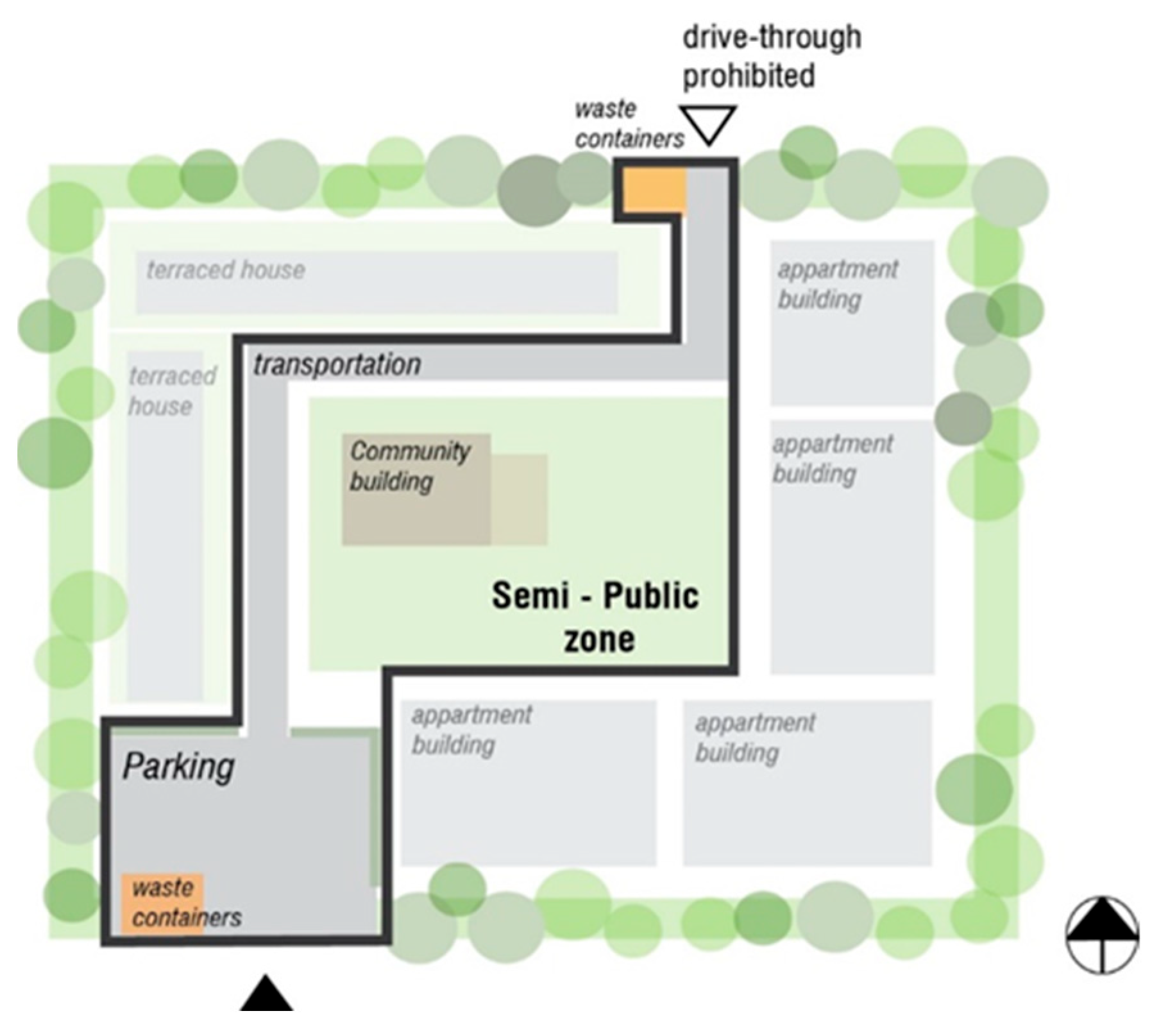

| Placement | Directly attached or connected to a residence unit; can be accessed mainly by the inhabitant. IN TERRACED HOUSING An outdoor private zone established near the building as a terrace, either on the entrance side (entrance via terrace) or on the garden side (Figure 3A). IN APARTMENTS An outdoor private zone consisting of apartment balconies. | An access zone to residential entrances. IN TERRACED HOUSING Forms a semi-enclosed corridor connecting terraced houses’ entrances (Figure 4A). IN APARTMENTS Larger zone (could be multistorey) in front of an entrance to a residence or as a rooftop terrace (Figure 4B). | The remainder of the area that is placed within the property boundary (Figure 5). It is not entirely public due to sheltering (Figure 1) and the absence of flow-through traffic. | Zone along the outer boundary of the construction area. |

| Function and character | A personal, enclosed outdoor space. A scent-free and noise-free private spot, providing privacy from passers-by but with an outlook to semi-private zone. Provides an opportunity for inhabitants to decide about the finishing materials and vegetation (within the accepted range, see paragraph: Design Considerations). IN TERRACED HOUSING A private zone on the garden side of a terraced house could be divided by a shed on one side and a planted green screen on the other. With a garden gate (dotted line, Figure 3A), the private zone can be clearly marked while allowing visibility of those passing by. A pergola can be used to create a form of overhead screening. The terrace could also potentially be covered. IN APARTMENTS The balconies are fully screened from neighbors and create an outdoor apartment room (Figure 3B). | An area designated for social interaction and sharing communal facilities among neighbors. Parking options if necessary. Can accommodate the opportunity for cultivating vegetables in designated areas. | Meeting places can include a community house, workshop, greenhouse, and more. Transportation to and from the area, delivery of goods should be organized with consideration for the residents’ communal needs. Parking is available near the first residences (Figure 5), but not directly on the site; however, there is access for unloading/moving. | Vegetation-based sheltering layer A wide zone of minimum 5 meters planted with shrub vegetation and smaller trees. If the zone is wide enough, a small recreational path in the middle can be included. Placements of solid waste station should be considered in this zone (Figure 5). Scent-experience layer. In this zone the shrub species with low/minimal scent may be allowed (see paragraph: Design considerations). |

| Health benefits and supportive features for people with MCS | Scent-dependent on the user. Preferably not north-facing for daytime sun exposure benefit. Reduces stress from exposure to uncontrollable factors expected in outdoor spaces. Provides option for self-controlled contact with nature | Scent-free. Gives opportunity for social contact with closest neighbors that can be avoided if necessary. Provides options of hands-on nature contact (e.g., vegetable gardens). | Scent-free. Supports social contact opportunities with larger groups of inhabitants. | Opportunities to experience low volume scented vegetation. Nature recreation opportunities (walking, running). |

3.3. Design Recommendations

3.3.1. Vegetation Selection

3.3.2. Outdoor Materials Selection

4. Discussion

4.1. Experience of Outdoor Environments by Individuals with MCS

4.2. The Role of Design Principles in the Well-Being of Individuals with MCS

4.2.1. Design for Physical Control of Environmental Triggers

4.2.2. Enhancing Social Relations and Well-Being Through Semi-Spaces

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSC | Multiple Chemical Sensitivity |

Appendix A

- Q 10 Are there any of the current outdoor surface materials on your home that, to a greater or lesser extent, trigger your MCS?

- Q 18 How important is it for you to have access to a private outdoor area?

- Q 19 How important is it for you to have access to a shared outdoor area?

- Q 21 How important is it for you to have a shared outdoor kitchen?

- Q 22 How important is it for you to have a private outdoor kitchen?

- Q 23 How important is it for you to have a sense of community with your neighbours?

- Q 24 How important is it that your private garden/terrace is (or can be) fully or partially covered?

- Q 29 What are your experiences with multi-storey housing?

- Q 30 What are your experiences with balconies and their use?

- Q 32 What are your experiences with shared facilities and their use?

- Q 35 What are your experiences with scented garden plants, e.g., lilac, lavender, roses?

- Q 36 What are your experiences with spending time in a garden with flowering plants?

- Q 37 What are your experiences with the smell of wet wood?

- Q 68 To what extent do you experience problems with outdoor materials such as untreated wood?

- Q 70 To what extent do you experience problems with outdoor materials such as painted wood?

- Q 72 To what extent do you experience problems with outdoor materials such as plastered/lime-washed surfaces?

- Q 74 To what extent do you experience problems with outdoor materials such as steel?

- Q 94 How many of your neighbours (also with MCS) would you like to meet indoors at one time?

- Q 95 How many of your neighbours (also with MCS) would you like to meet with outdoors at one time?

- Q 96 What walking distance is acceptable for you from parking space to front door? (On the housing site’s property)?

Appendix B

| Latin Name | English Name |

|---|---|

| Astilbe japonica “Montgomery” | Astilbe “Montgomery” |

| Astilbe chinensis | Astilbe |

| Astilbe arendsii | Astilbe |

| Campanula persicifolia | Peach-leaved bellflower |

| Campanula trachelium | Nettle-leaved bellflower |

| Campanula poscharskyana “Stella” | Serbian bellflower “Stella” |

| Cerastium tomentosum | Snow-In-Summer |

| Gentiana acaulis | Stemless gentian |

| Hylotelephium telephium | Orpine |

| Lathyrus latifolius “Alba” | Perennial Sweet Pea |

| Rudbeckia fulgida “Goldsturm” | Black-Eyed Susan |

| Scabiosa columbaria “Butterfly Blue” | Pincushion Flower “Butterfly Blue” |

| Veronica austrica “True Blue” | Austrian speedwell |

| Latin Name | English Name |

|---|---|

| Acer ginnala | Amur maple |

| Acer japonicum | Fullmoon maple |

| Acer negundo | Ash-leaved maple |

| Acer palmatum | Japanese dwarf maple |

| Acer platanoides | Norway maple |

| Aesculus carnea | Red horse-chestnut |

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi | Bearberry |

| Aucuba japonica | Aucuba/Japanese laurel |

| Callicarpa bodinieri | Bodinier’s beautyberry |

| Cotoneaster horizontalis | Rock cotoneaster |

| Decaisnea fargesii | Blue bean |

| Enkianthus campanulatus | Redvein enkianthus |

| Euonymus europaeus | European spindle |

| Euonymus fortunei | Creeping spindle |

| Exochorda racemosa | Pearl bush |

| Hebe armstrongii | Armstrong’s hebe |

| Hibiscus syriacus | Rose of Sharon |

| Hippophae rhamnoides | Sea buckthorn |

| Hypericum erectum “Gemo” | Narrow leaved St. John’s Wort |

| Kalmia angustifolia | Sheep laurel |

| Lonicera ledibourii | Twinberry Honeysuckle |

| Mespilus germanica | Medlar |

| Pachysandra terminalis | Japanese spurge |

| Parrotia persica | Persian ironwood |

| Pernettya mucronata | Prickly heath |

| Physocarpus opulifolius | Nicebark |

| Pieris japonica | Japanese andromeda |

| Platanus acerifolia | London plane |

| Potentilla fruticosa | Shrubby cinquefoil |

| Prunus serotina | Black cherry |

| Prunus tenella | Swarf Russian almond |

| Prunus triloba | Flowering almond |

| Latin Name | English Name |

|---|---|

| Araucaria araucana | Monkey puzzle tree |

| Taxus spp. | Yew (various species) |

| Latin Name | English Name |

|---|---|

| Campsis radicans | Trumpet vine/Trumpet creeper |

| Celastrus orbiculata | Oriental bittersweet |

| Clematis montana | Mountain clematis (some varieties can have fragrance) |

| Clematis alpine | Alpine clematis |

| Clematis hybrid | Large-flowered clematis |

| Clematis tangutica | Golden clematis |

| Clematis viticella | Italian clematis |

| Jasminum nudiflorum | Winter jasmine |

| Lonicera hec. “Goldflame” | Goldflame honeysuckle |

| Parthenocissus inserta | Thicket creeper or Woodbine |

| Parthenocissus quinqifolia engelmannii | Virginia creeper |

| Parthenocissus tricuspidata “Veitchii” | Boston Ivy (Veitchii cultivar) |

| Vitis vinifera | Common crape vine |

| Latin Name | English Name |

|---|---|

| Alchemilla mollis | Lady’s mantle |

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi | Bearberry |

| Asarum europaeum | European wild ginger |

| Brunnera macrophylla | Siberian bugloss |

| Fragaria vesca | Wild strawberry |

| Gypsophila paniculata | Baby’s breath |

| Leptinella minima | Brass buttons |

| Pachysandra terminalis | Japanese spurge |

| Symphoricarpus chenaultii “Hancock” | Coralberry/Hancock snowberry |

| Vinca minor | Lesser periwinkle |

References

- Del Casale, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Mosca, A.; Pomes, L.M.; Fiaschè, F.; Bonanni, L.; Borro, M.; Gentile, G.; Martelletti, P.; Simmaco, M. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome: A Principal Component Analysis of Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molot, J.; Sears, M.; Anisman, H. Multiple chemical sensitivity: It’s time to catch up to the science. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 151, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Soler, B.; Gutiérrez-Pastor, A.; Palazón-Bru, A.; Vallejo-Ortega, J.; Méndez-Jover, Á.; Santano-Pérez, C.; Seguí-Pérez, C.; Seguí-Pérez, M.; Cascant-Pérez, S.; López-Corbalán, J.C.; et al. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity: A Sickness of Suffering, Not of Dying. Descriptive Study of 33 Cases. Health 2025, 17, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. National Prevalence and Effects of Multiple Chemical Sensitivities. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e152–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.M.; Price, D.; Torriero, A.A.J.; Symonds, M.R.E.; Suphioglu, C. Impact of Fungal Spores on Asthma Prevalence and Hospitalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, G.; Tremblay, M.È.; Allard, R. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity Syndrome, an Integrative Approach to Identifying the Pathophysiological Mechanisms; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P.R.; Elms, A.N.M.; Ruding, L.A. Perceived treatment efficacy for conventional and alternative therapies reported by persons with multiple chemical sensitivity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, K.; Hammel, G.; Fleming, M.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C. Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS)—A guide for dermatologists on how to manage affected individuals. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2020, 18, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, R.B.; Palmer, R.F.; Rincon, R.; Viramontes, J.N.; Walker, T.; Jaén, C.R.; Miller, C.S. Does improving indoor air quality lessen symptoms associated with chemical intolerance? Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2022, 23, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, L.; Patton, R.; John, M. The impact of multiple chemical sensitivity on people’s social and occupational functioning; a systematic review of qualitative research studies. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 132, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, E.A.; Bosworth, H.B.; Noel, P.H.; Wolff, J.L.; Damush, T.M.; Mciver, L. Supporting self-management for patients with complex medical needs: Recommendations of a working group. Chronic Illn. 2007, 3, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Vogel, V.M. Sickness-related dysfunction in persons with self-reported multiple chemical sensitivity at four levels of severity. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrendt Bjerregaard, A.; Schovsbo, S.U.; Gormsen, L.K.; Skovbjerg, S.; Eplov, L.F.; Linneberg, A.; Cedeño-Laurent, J.G.; Jørgensen, T.; Dantoft, T.M. Social economic factors and the risk of multiple chemical sensitivity in a Danish population-based cross-sectional study: Danish Study of Functional Disorders (DanFunD). BMJ Open 2023, 13, e064618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, A.; Hojo, S.; Azuma, K.; Mizuki, M.; Miyata, M.; Ogura, H.; Sakabe, K.; Tsurikisawa, N.; Oshikata, C.; Okumura, J. Comparison of environmental intolerances and symptoms between patients with multiple chemical sensitivity, subjects with self-reported electromagnetic hypersensitivity, patients with bronchial asthma, and the general population. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J. What Is Universal Design? Universal Design (UD) Is a Design Process That Enables and Empowers a Diverse Population by Improving Human Performance, Health and Wellness, and Social Participation. 2012. Available online: https://idea.ap.buffalo.edu/about/universal-design/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- World Health Organization and World Bank. World Report on Disability 2011; World Health Organization and World Bank: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wasley, J. Environments for the Chemically Sensitive as Models of Healthy Building Construction Issues of Ventilation. In 85th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, Architecture: Material and Imagined; Speck, L.W., Ed.; ACSA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer, L.L. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS): The Controversy and Relation to Interior Design. J. Inter. Des. 2004, 30, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology; Committee on Emerging Science on Indoor Chemistry. 6 Indoor Chemistry and Exposure. In Why Indoor Chemistry Matters; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585377/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 75001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molot, J.; Tabassum, F.; Tambasco, D.; Selke, M.S.; Kerr, K.; Bray, R.; Swales, J.; Oliver, L.C.; Fox, J. Challenging dated conceptions to advocate for evidence-informed care in multiple chemical sensitivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 805–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental Psychology and Sustainable Development: Expansion, Maturation, and Challenges. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.K.; Watkins, D.H. Evidence-Based Design for Multiple Building Types; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McNabola, A.; Broderick, B.; Gill, L. Reduced exposure to air pollution on the boardwalk in Dublin, Ireland. Measurement and prediction. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNabola, A.; Broderick, B.; Gill, L. The impacts of inter-vehicle spacing on in-vehicle air pollution concentrations in idling urban traffic conditions. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2009, 14, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, L.; Hu, Y.; Shao, J.; Chi, T. Deep learning architecture for air quality predictions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 22408–22417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sæbø, A.; Popek, R.; Nawrot, B.; Hanslin, H.M.; Gawronska, H.; Gawronski, S.W. Plant species differences in particulate matter accumulation on leaf surfaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 427–428, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.S.; Palmer, R.F.; Kattari, D.; Masri, S.; Ashford, N.A.; Rincon, R.; Perales, R.B.; Grimes, C.; Sundblad, D.R. What initiates chemical intolerance? Findings from a large population-based survey of U.S. adults. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rádis-Baptista, G. Do Synthetic Fragrances in Personal Care and Household Products Impact Indoor Air Quality and Pose Health Risks? J. Xenobiot. 2023, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredsdorff, L.; Nielsen, E. Evaluation of Selected Sensitizing Fragrance Substances. A LOUS follow-Up Project; Environmental Project No. 1840; Danish Environmental Protection Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.M. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity in the Clinical Setting: Although the cause and diagnosis of this condition remain controversial, the patient’s concerns should be heeded. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2007, 107, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.; Miller, C.S.; Palmer, R.F.; Ashford, N. Toxicant-induced loss of tolerance for chemicals, foods, and drugs: Assessing patterns of exposure behind a global phenomenon. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucco, G.M.; Doty, R.L. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. Brain Sci. 2021, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario; The Task Force on Environmental Health. Care Now an Action Plan to Improve Care for People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Fibromyalgia (FM) and Environmental Sensitivities/Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (ES/MCS) [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/moh-task-force-on-environmental-health-report-dec-2018-en-2023-03-09.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hojo, S.; Mizukoshi, A.; Azuma, K.; Okumura, J.; Ishikawa, S.; Miyata, M.; Mizuki, M.; Ogura, H.; Sakabe, K. Survey on changes in subjective symptoms, onset/trigger factors, allergic diseases, and chemical exposures in the past decade of Japanese patients with multiple chemical sensitivity. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.C. Outdoor-indoor air pollution in urban environment: Challenges and opportunity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, A.; Mudu, P. How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces’ mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective—With implications for urban planning. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.; Evans, G.W. Environmental stressors, urban design and planning: Implications for human behaviour and health. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Thomson, H.; Kearns, A.; Petticrew, M. Understanding the Psychosocial Impacts of Housing Type: Qualitative Evidence from a Housing and Regeneration Intervention. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lausen, E.D.; Jensen, M.B.; Lygum, V.L. Residential Outdoor Environments for Individuals with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081243

Lausen ED, Jensen MB, Lygum VL. Residential Outdoor Environments for Individuals with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081243

Chicago/Turabian StyleLausen, Emilia Danuta, Marina Bergen Jensen, and Victoria Linn Lygum. 2025. "Residential Outdoor Environments for Individuals with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081243

APA StyleLausen, E. D., Jensen, M. B., & Lygum, V. L. (2025). Residential Outdoor Environments for Individuals with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081243