Weight Misperception, Weight Dissatisfaction, and Weight Change Among a Swiss Population-Based Adult Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Ethical Statement

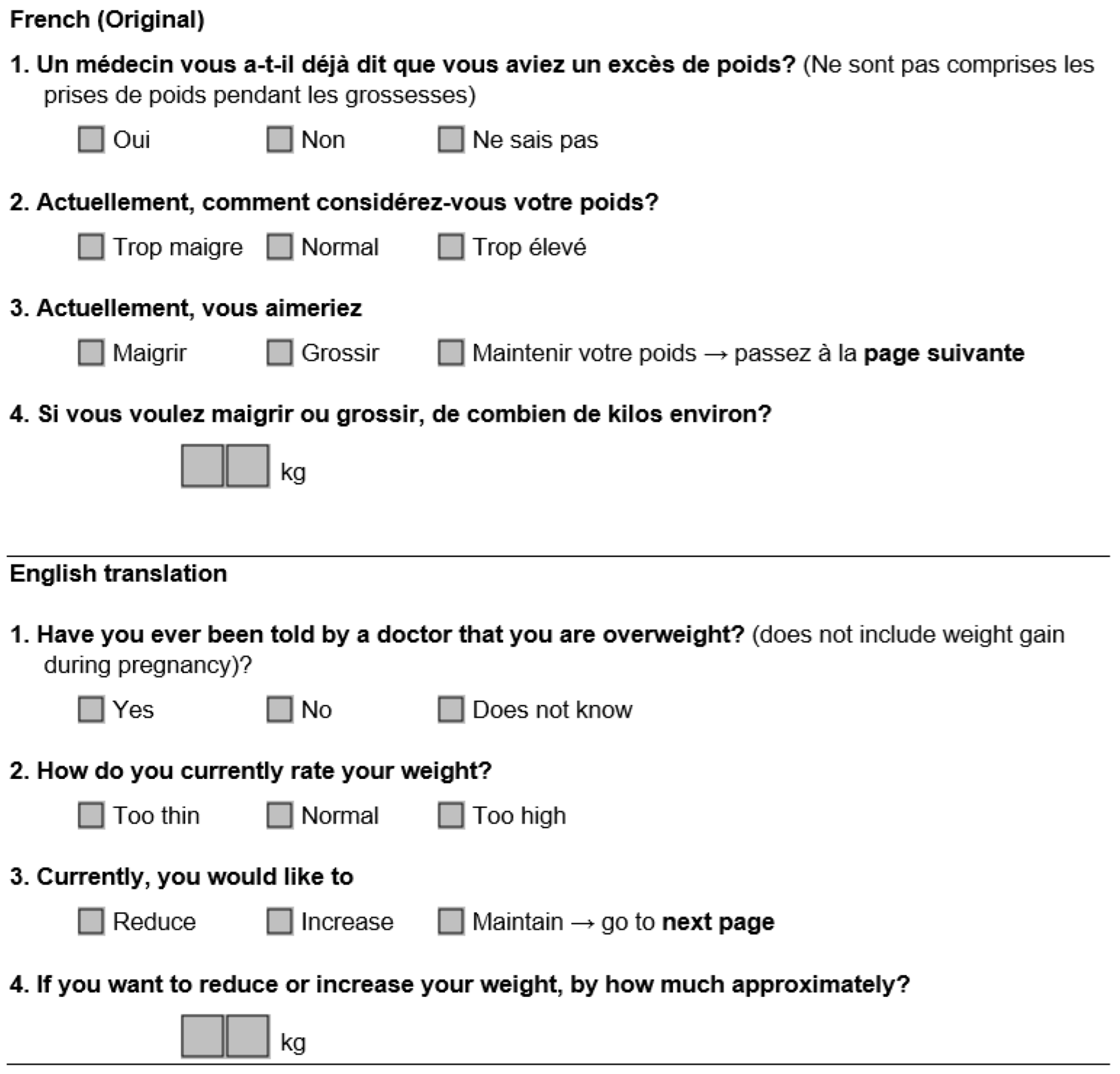

2.3. Weight Misperception and Weight Dissatisfaction

2.4. Weight Change

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Eligibility, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Weight Misperception: Characteristics of Participants and Effect on 5-Year Weight Changes

3.3. Weight Dissatisfaction: Characteristics of Participants and Effect on 5-Year Weight Changes

3.4. Weight Misperception or Dissatisfaction: Effect on 10-Year Weight Changes

4. Discussion

4.1. Weight Misperception or Dissatisfaction: Effect on Weight

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| FFQ | Food frequency questionnaire |

| TEI | Total energy intake |

Appendix A

Weight Questionnaire

References

- Rouiller, N.; Marques-Vidal, P. Prevalence and determinants of weight misperception in an urban Swiss population. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, w14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrard, I.; Kruseman, M.; Marques-Vidal, P. Desire to lose weight, dietary intake and psychological correlates among middle-aged and older women. The CoLaus study. Prev. Med. 2018, 113, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutin, A.R.; Terracciano, A. Body weight misperception in adolescence and incident obesity in young adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancourt, D.; Thurston, I.B.; Sonneville, K.R.; Milliren, C.E.; Richmond, T.K. Longitudinal impact of weight misperception and intent to change weight on body mass index of adolescents and young adults with overweight or obesity. Eat. Behav. 2017, 27, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.R.; Thurston, I.B.; Milliren, C.E.; Kamody, R.C.; Gooding, H.C.; Richmond, T.K. Helpful or harmful? Prospective association between weight misperception and weight gain among overweight and obese adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prnjak, K.; Hay, P.; Mond, J.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Lonergan, A.; Mitchison, D. The distinct role of body image aspects in predicting eating disorder onset in adolescents after one year. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Hunger, J.M.; Daly, M. Perceived weight status and risk of weight gain across life in US and UK adults. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1721–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Daly, M. Self-perceived overweight, weight loss attempts, and weight gain: Evidence from two large, longitudinal cohorts. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Wilson, A. Does dissatisfaction with, or accurate perception of overweight status help people reduce weight? Longitudinal study of Australian adults. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraia, B.A.; Leung, C.W.; Tomiyama, A.J.; Ritchie, L.D.; Crawford, P.B.; Epel, E.S. Drive for thinness in adolescents predicts greater adult BMI in the Growth and Health Study cohort over 20 years. Obesity 2021, 29, 2126–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Haughton, C.F.; Frisard, C.; Pbert, L.; Geer, C.; Lemon, S.C. Perceived weight status and weight change among a U.S. adult sample. Obesity 2017, 25, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmann, M.; Mayor, V.; Vidal, P.M.; Bochud, M.; Pecoud, A.; Hayoz, D.; Paccaud, F.; Preisig, M.; Song, K.S.; Yuan, X.; et al. The CoLaus study: A population-based study to investigate the epidemiology and genetic determinants of cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2008, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriota, P.; Rezzi, S.; Guessous, I.; Marques-Vidal, P. No Association between Vitamin D and Weight Gain: A Prospective, Population-Based Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Stringhini, S.; Vollenweider, P.; Waeber, G.; Marques-Vidal, P. Socio-demographic and behavioural determinants of weight gain in the Swiss population. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer-Borst, S.; Costanza, M.C.; Pechere-Bertschi, A.; Morabia, A. Twelve-year trends and correlates of dietary salt intakes for the general adult population of Geneva, Switzerland. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.; Huot, I.; Morabia, A. Amélioration des performances d’un questionnaire alimentaire semi-quantitatif comparé à un rappel des 24 heures. Santé Publ. 1995, 7, 403–4013. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, A.; Kersbergen, I.; Sutin, A.; Daly, M.; Robinson, E. A systematic review of the relationship between weight status perceptions and weight loss attempts, strategies, behaviours and outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzas, C.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Garcia, S.; Mateos, D.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Goday, A.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gomez, A.M.; et al. Desired weight loss and its association with health, health behaviors and perceptions in an adult population with weight excess: One-year follow-up. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 848055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrard, I.; Bayard, A.; Grisel, A.; Jotterand Chaparro, C.; Bucher Della Torre, S.; Chatelan, A. Associations Between Body Weight Dissatisfaction and Diet Quality in Women With a Body Mass Index in the Healthy Weight Category: Results From the 2014–2015 Swiss National Nutrition Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1492–1502.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen Alcolea, F.; Lopez-Gil, J.F.; Tarraga Lopez, P.J. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet, level of physical activity and body dissatisfaction in subjects 16–50 years old in the Region of Murcia, Spain. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. 2021, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawardi, N.M.; AlTamimi, A.A.; AlMarzooqi, M.A.; Alrasheed, L.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Associations of Body Dissatisfaction With Lifestyle Behaviors and Socio-Demographic Factors Among Saudi Females Attending Fitness Centers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 611472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, Z.J.; Rodriguez, P.; Wright, D.R.; Austin, S.B.; Long, M.W. Estimation of Eating Disorders Prevalence by Age and Associations With Mortality in a Simulated Nationally Representative US Cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5-Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, E.M.; Gomes, F.V.S.; Vaz, A.R.; Pinto-Bastos, A.; Machado, P.P.P. Prevalence of eating disorders and picking/nibbling in elderly women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Follow-Up 1 to 2 | Follow-Up 2 to 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1452) | Yes (n = 279) | p-Value | No (n = 917) | Yes (n = 123) | p-Value | |

| Women (%) | 915 (63.0) | 224 (80.3) | <0.001 | 551 (60.1) | 100 (81.1) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 56.4 ± 10.1 | 53.3 ± 8.7 | <0.001 | 61.7 ± 9.7 | 57.5 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Born in Switzerland (%) | 976 (67.2) | 195 (69.9) | 0.38 | 626 (68.3) | 83 (68.0) | 0.96 |

| Educational level (%) | 0.087 | 0.21 | ||||

| High | 398 (27.4) | 94 (33.7) | 264 (28.8) | 38 (31.1) | ||

| Middle | 423 (29.1) | 79 (28.3) | 272 (29.7) | 43 (35.2) | ||

| Low | 631 (43.5) | 106 (38.0) | 381 (41.5) | 41 (33.6) | ||

| Living as a couple (%) | 799 (55.0) | 147 (52.7) | 0.47 | 602 (65.6) | 80 (65.6) | 0.99 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.1 ± 1.9 | 23.5 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | 22.1 ± 1.9 | 23.7 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Waist (cm) | 81.2 ± 8.0 | 84.4 ± 7.4 | <0.001 | 80.6 ± 8.3 | 82.6 ± 7.8 | 0.012 |

| Abdominal obesity (%) | 84 (5.8) | 57 (20.4) | <0.001 | 38 (4.1) | 14 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Overweight diagnosis (%) | 47 (3.3) | 37 (13.6) | <0.001 | 23 (2.5) | 18 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinker (%) | 1136 (78.2) | 228 (81.7) | 0.19 | 697 (80.0) | 100 (87.0) | 0.076 |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.78 | |||||

| Never | 653 (45.0) | 123 (44.1) | 0.67 | 409 (44.6) | 57 (46.7) | |

| Former | 483 (33.3) | 100 (35.8) | 340 (37.1) | 46 (37.7) | ||

| Current | 316 (21.8) | 56 (20.1) | 168 (18.3) | 19 (15.6) | ||

| Hypertension (%) | 380 (26.2) | 60 (21.5) | 0.10 | 262 (28.6) | 25 (20.5) | 0.060 |

| Diabetes (%) | 38 (2.6) | 2 (0.7) | § 0.054 | 22 (2.4) | 2 (1.6) | § 0.60 |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 1660 (1329–2075) | 1624 (1240–1982) | † 0.036 | 1660 [1324–2031] | 1560 [1107–1878] | † 0.004 |

| Follow-Up 1 to 2 | Follow-Up 2 to 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1452) | Yes (n = 279) | p-Value | No (n = 917) | Yes (n = 123) | p-Value | |

| Bivariate | ||||||

| Weight change (kg) | 0.7 ± 3.7 | 1.1 ± 4.4 | 0.103 | 0.1 ± 3.2 | 0.1 ± 4.1 | 0.873 |

| Weight change (%) | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||||

| Loss > 5 kg | 56 (3.9) | 19 (6.8) | 43 (4.7) | 12 (9.8) | ||

| Stable | 1269 (87.4) | 221 (79.2) | 827 (90.2) | 100 (82.0) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | 127 (8.8) | 39 (14.0) | 47 (5.1) | 10 (8.2) | ||

| Multivariable | ||||||

| Weight change (kg) | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.74 ± 0.23 | 0.865 | 0.11 ± 0.12 | −0.35 ± 0.33 | 0.196 |

| Weight change | ||||||

| Loss > 5 kg | - | 2.20 (1.24–3.93) | 0.007 | - | 3.15 (1.44–6.90) | 0.004 |

| Stable | - | 1 (ref) | - | 1 (ref) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | - | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.142 | - | 1.98 (0.89–4.40) | 0.092 |

| Weight change, weighted | ||||||

| Loss > 5 kg | - | 2.11 (1.15–3.88) | 0.015 | - | 2.89 (1.22–6.86) | 0.016 |

| Stable | - | 1 (ref) | - | 1 (ref) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | - | 1.38 (0.91–2.09) | 0.127 | - | 2.18 (0.93–5.09) | 0.072 |

| Follow-Up 1 to 2 | Follow-Up 2 to 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1226) | Yes (n = 505) | p-Value | No (n = 818) | Yes (n = 221) | p-Value | |

| Women (%) | 744 (60.7) | 395 (78.2) | <0.001 | 479 (58.6) | 171 (77.4) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 57.0 ± 10.1 | 53.0 ± 8.8 | <0.001 | 62.2 ± 9.8 | 57.6 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Born in Switzerland (%) | 841 (68.6) | 330 (65.3) | 0.19 | 557 (68.1) | 152 (68.8) | 0.85 |

| Educational level (%) | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||||

| High | 317 (25.9) | 175 (34.7) | 224 (27.4) | 78 (35.3) | ||

| Middle | 353 (28.8) | 149 (29.5) | 245 (30.0) | 70 (31.7) | ||

| Low | 556 (45.4) | 181 (35.8) | 349 (42.7) | 73 (33.0) | ||

| Living as a couple (%) | 686 (56.0) | 260 (51.5) | 0.090 | 545 (66.6) | 137 (62.0) | 0.20 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.9 ± 1.9 | 23.2 ± 1.4 | <0.001 | 22.0 ± 1.9 | 23.3 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Waist (cm) | 81.1 ± 8.1 | 83.2 ± 7.6 | <0.001 | 80.5 ± 8.4 | 82.1 ± 7.6 | 0.012 |

| Abdominal obesity (%) | 68 (5.5) | 73 (14.5) | <0.001 | 33 (4.0) | 19 (8.6) | 0.006 |

| Overweight diagnosis (%) | 40 (3.3) | 44 (8.8) | <0.001 | 19 (2.4) | 22 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinker (%) | 949 (77.4) | 415 (82.2) | 0.027 | 625 (80.5) | 172 (81.9) | 0.66 |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.41 | 0.29 | ||||

| Never | 553 (45.1) | 223 (44.2) | 376 (46.0) | 90 (40.7) | ||

| Former | 402 (32.8) | 181 (35.8) | 301 (36.8) | 85 (38.5) | ||

| Current | 271 (22.1) | 101 (20.0) | 141 (17.2) | 46 (20.8) | ||

| Hypertension (%) | 332 (27.1) | 108 (21.4) | 0.013 | 237 (29.0) | 50 (22.6) | 0.060 |

| Diabetes (%) | 35 (2.9) | 5 (1.0) | § 0.020 | 21 (2.6) | 3 (1.4) | § 0.29 |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 1671 [1342–2076] | 1611 [1256–2007] | † 0.011 | 1678 [1347–2043] | 1527 [1140–1903] | † < 0.001 |

| Follow-Up 1 to 2 | Follow-Up 2 to 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1226) | Yes (n = 505) | p-Value | No (n = 818) | Yes (n = 221) | p-Value | |

| Bivariate | ||||||

| Weight change (kg) | 0.8 ± 3.7 | 0.8 ± 4.0 | 0.988 | 0.1 ± 3.2 | 0.1 ± 3.7 | 0.871 |

| Weight change (%) | 0.023 | 0.038 | ||||

| Loss > 5 kg | 46 (3.8) | 29 (5.7) | 37 (4.5) | 18 (8.1) | ||

| Stable | 1073 (87.5) | 417 (82.6) | 740 (90.5) | 187 (84.6) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | 107 (8.7) | 59 (11.7) | 41 (5.0) | 16 (7.2) | ||

| Multivariable | ||||||

| Weight change (kg) | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 0.021 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | −0.40 ± 0.25 | 0.040 |

| Weight change | ||||||

| Loss > 5 kg | - | 1.88 (1.12–3.17) | 0.017 | - | 2.88 (1.45–5.74) | 0.003 |

| Stable | - | 1 (ref) | - | 1 (ref) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | - | 1.07 (0.74–1.55) | 0.706 | - | 1.37 (0.70–2.69) | 0.363 |

| Weight change, weighted | ||||||

| Loss > 5 kg | - | 1.80 (1.10–2.92) | 0.018 | - | 2.77 (1.26–6.08) | 0.011 |

| Stable | - | 1 (ref) | - | 1 (ref) | ||

| Gain > 5 kg | - | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 0.732 | - | 1.45 (0.73–2.91) | 0.292 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manca, L.; Marques-Vidal, P. Weight Misperception, Weight Dissatisfaction, and Weight Change Among a Swiss Population-Based Adult Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081237

Manca L, Marques-Vidal P. Weight Misperception, Weight Dissatisfaction, and Weight Change Among a Swiss Population-Based Adult Sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081237

Chicago/Turabian StyleManca, Lucy, and Pedro Marques-Vidal. 2025. "Weight Misperception, Weight Dissatisfaction, and Weight Change Among a Swiss Population-Based Adult Sample" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081237

APA StyleManca, L., & Marques-Vidal, P. (2025). Weight Misperception, Weight Dissatisfaction, and Weight Change Among a Swiss Population-Based Adult Sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081237