Youth Exposed to Armed Conflict: The Homeroom Teacher as a Protective Agent Promoting Student Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk and Resilience in the Face of Protracted Armed Conflict

1.2. The School and Homeroom Teacher in Times of Crisis

1.2.1. Teacher Life Satisfaction

1.2.2. Teacher Sense of Self-Efficacy

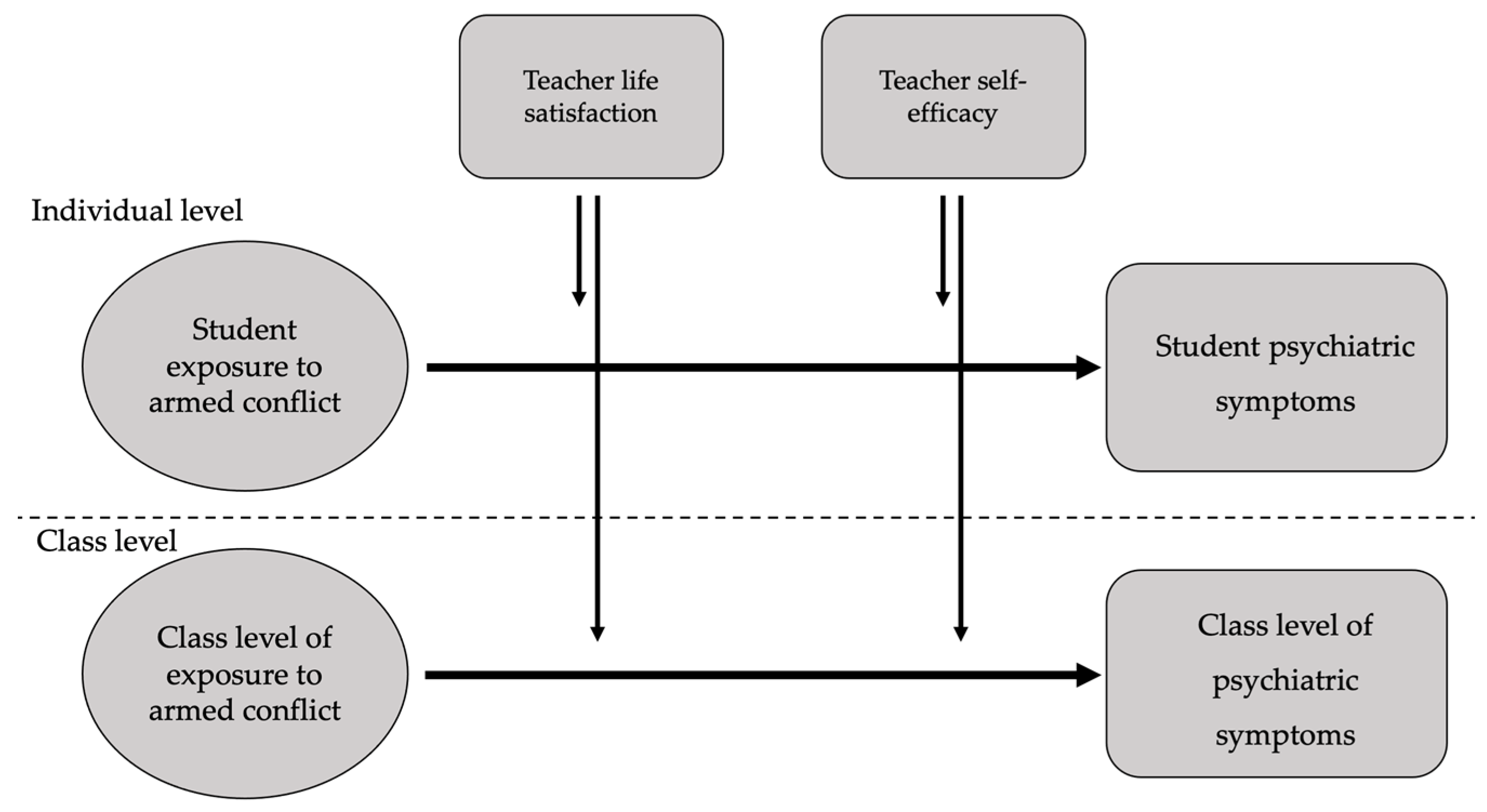

1.3. The Present Study

1.4. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Student Socio-Demographic Background

2.2.2. Student Exposure to Armed Conflict Events

2.2.3. Student Psychological Distress

2.2.4. Student Post-Traumatic Symptoms

2.2.5. Teacher Socio-Demographic Background

2.2.6. Teacher Satisfaction with Life Scale

2.2.7. Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

3.2. Hypotheses Testing

3.2.1. Testing Hypothesis 1: Student PLE and Psychiatric Symptoms

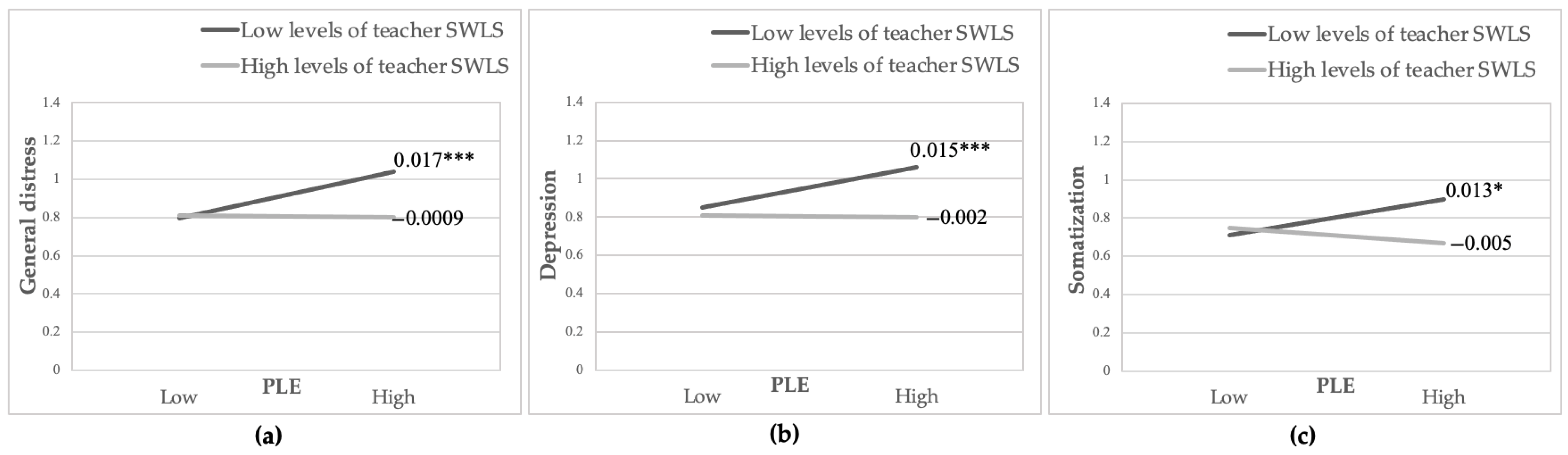

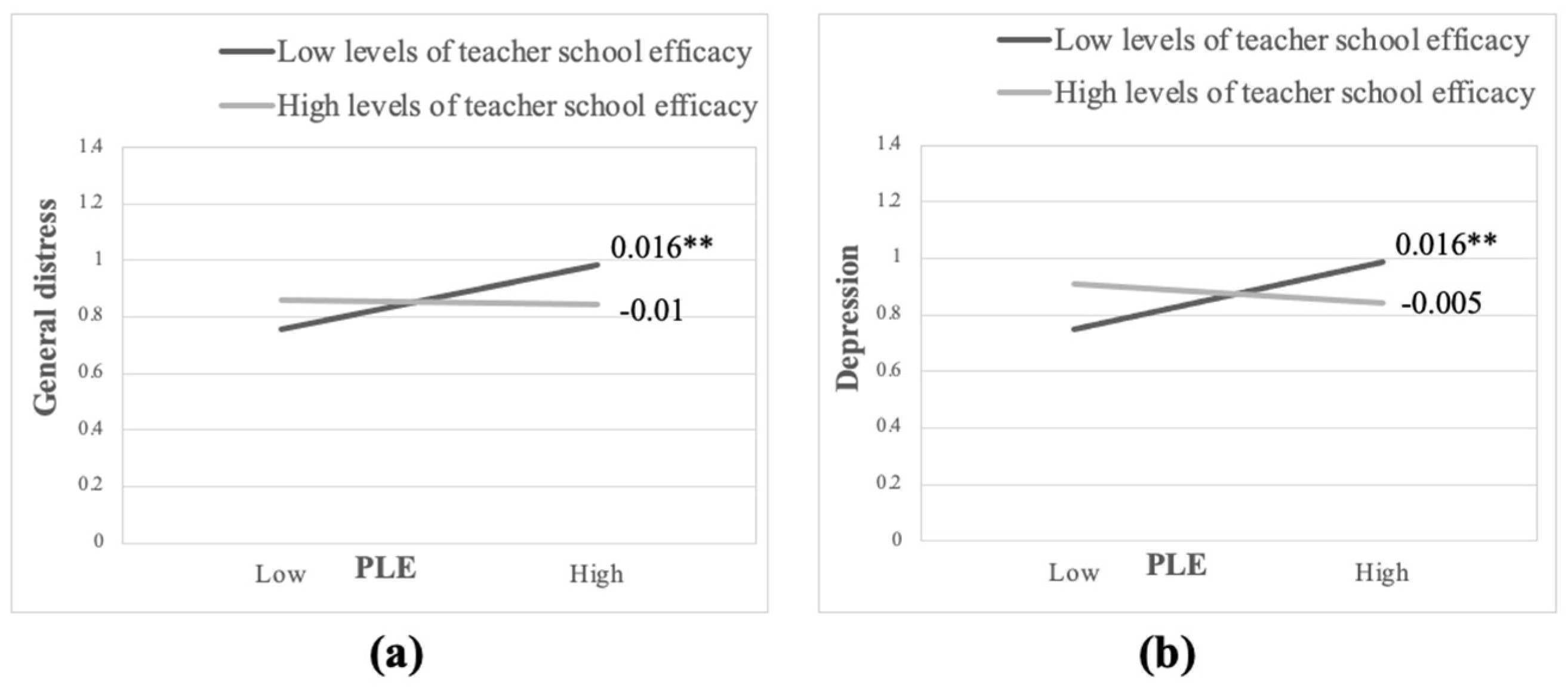

3.2.2. Testing Hypothesis 2: Homeroom Teacher Life Satisfaction and Self-Efficacy as Protective Factors

3.3. Robustness Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Exposure to Armed Conflict and Youth Psychiatric Symptoms

4.2. The Moderating Role of Homeroom Teacher Life-Satisfaction and Self-Efficacy

4.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cummings, E.M.; Merrilees, C.E.; Taylor, L.K.; Mondi, C.F. Developmental and social-ecological perspectives on children, political violence, and armed conflict. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N. Depression in youth exposed to disasters, terrorism and political violence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, A.; Geiger, K.; Glass, N. Caregiver and family-focused interventions for early adolescents affected by armed conflict: A narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 134, 106361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Peer, A. Children’s Reactions to war, armed conflict and displacement: Resilience in a social climate of support. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, V. Posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation among Syrian refugee children and adolescents resettled in Lebanon and Jordan. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 89, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaias, L.M.; Johnson, S.L.; White, R.M.B.; Pettigrew, J.; Dumka, L. Positive school climate as a moderator of violence exposure for Colombian adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, L.; Aber, J.L.; Crossman, A. Risk or resource: Does school climate moderate the influence of community violence on children’s social-emotional development in the Democratic Republic of Congo? Dev. Sci. 2019, 22, e12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S. War and conflict: Addressing the psychosocial needs of child refugees. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2019, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablon, Y.B.; Itzhaky, H. The contribution of school experience to students’ resilience following a terror-related homicide. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablon, Y.B.; Itzhaky, H. Children’s relationships with homeroom teachers as a protective factor in times of terror. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2013, 30, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.; Gelkopf, M.; Heineberg, Y.; Zimbardo, P.A. School-based intervention for reducing posttraumatic symptomatology and intolerance during political violence. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 108, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.G.; Holt, M.K.; Kwong, L.; Reid, G.; Xuan, Z.; Comer, J.S. School- and classroom-based supports for children following the 2013 Boston marathon attack and manhunt. Sch. Ment. Health 2015, 7, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A. Transcending the reality of war and conflict: Effects of a positive psychology school-based program on adolescents’ mental health, compassion and hopes for peace. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 16, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormez, V.; Kılıç, H.N.; Orengul, A.C.; Demir, M.N.; Mert, E.B.; Makhlouta, B.; Kinikfand, K.; Semerci, B. Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected Syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Mayer, Y.; Gilady, A. Teachers as agents of clinical practice during armed conflict. In Handbook of Political Violence and Children: Psychosocial Effects, Intervention, and Prevention Policy; Greenbaum, C.A., Haj-Yahia, M.M., Hamilton, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 344–368. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, N.L.; Stokar, N.; Ginat-Frolich, R.; Ziv, Y.; Abu-Jufar, I.; Lopes, B.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Brom, D. Children and youth services review building resilience intervention (BRI) with teachers in Bedouin communities: From evidence informed to evidence based. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 87, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, M.; Smajkic, A.; Zeric, D.; Dzidowska, M.; Gebre-Medhin, J.; Van Halem, J. Mental health and coping in a war situation: The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2004, 36, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Mann, S. Effects of war, terrorism and armed conflict on young children: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, T.; Itzhaky, L.; Bronstein, I.; Solomon, Z. Psychopathology, risk, and resilience under exposure to continuous traumatic stress: A systematic review of studies among adults living in Southern Israel. Traumatology 2018, 24, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-graff, L.E.; Cummings, E.M. The Israeli—Palestinian conflict: Effects on youth adjustment, available interventions, and future research directions. Dev. Rev. 2017, 43, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A. Effects of war and armed conflict on adolescents’ psychopathology and well-being: Measuring political life events among youth. Terror. Political Violence 2021, 34, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A.; Slone, M. The resilience function of character strengths in the face of war and protracted conflict. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Mayer, Y. Gender differences in mental health consequences of exposure to political violence among Israeli adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 58, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakat, E.; Schiff, M. Religiosity: Protective or risk factor for posttraumatic distress among adolescents who were exposed to different types of acts of political violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP3914–NP3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuttman-Shwartz, O. Children and adolescents facing a continuous security threat: Aggressive behavior and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 69, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, E.G.; Fayyad, J.; Karam, A.N.; Melhem, N.; Mneimneh, Z.; Dimassi, H.; Tabet, C.C. Outcome of depression and anxiety after war: A prospective epidemiologic study of children and adolescents. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A. Psychiatric effects of protracted conflict and political life events exposure among adolescents in Israel: 1998–2011. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.D.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Musa, G.J.; Eisenberg, R.; Bresnahan, M.; Wicks, J.; Weinberger, A.H.; Fan, B.; Hoven, C.W. Exposure to mass disaster and probable panic disorder among children in New York City. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 138, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, K.; Motsan, S.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Feldman, R. From mothers to children and back: Bidirectional processes in the cross-generational transmission of anxiety from early childhood to early adolescence. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khodary, B.; Samara, M. The relationship between multiple exposures to violence and war trauma, and mental health and behavioural problems among Palestinian children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khodary, B.; Samara, M. The mediating role of trait emotional intelligence, prosocial behaviour, parental support and parental psychological control on the relationship between war trauma, and PTSD and depression. J. Res. Pers. 2019, 81, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shechner, T. Psychiatric consequences for Israeli adolescents of protracted political violence: 1998–2004. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stensland, S.Ø.; Zwart, J.A.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Dyb, G. The headache of terror: A matched cohort study of adolescents from the Utøya and the HUNT Study. Neurology 2018, 90, e111–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amone-P’Olak, K.; Omech, B. Predictors of somatic symptomatology in war-affected youth in northern Uganda: Findings from the ways study. Psychol. Stud. 2020, 65, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A. Children affected by war and armed conflict: Parental protective factors and resistance to mental health symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitton, M.S.; Laufer, A. Children’s emotional and behavioral problems in the shadow of terrorism: The case of Israel. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 86, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.; Phogat, P. Effects on mental well-being of children facing armed conflict: A systemic review. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2018, 9, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Itani, L.; Jaalouk, D.; Fayyad, J.; Garcia, J.T.; Chidiac, F.; Karam, E. Mental health outcomes for war exposed children and adolescents in the Arab world. Arab. J. Psychiatry 2017, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A. Efficacy of a school-based primary prevention program for coping with exposure to political violence. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2008, 32, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Thompson, A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.; Besser, A.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Neria, Y. Dispositional optimism and self–esteem as competing predictors of acute symptoms of generalized anxiety disorders and dissociative experiences among civilians exposed to war trauma. Psychol. Trauma 2015, 7, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrisman, A.K.; Dougherty, J.G. Mass trauma: Disasters, terrorism, and war. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2014, 23, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenness, J.L.; Jager-Hyman, S.; Heleniak, C.; Beck, A.T.; Sheridan, M.A.; McLaughlin, K.A. Catastrophizing, rumination, and reappraisal prospectively predict adolescent PTSD symptom onset following a terrorist attack. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. Fam. Relat. 2002, 51, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevell, M.C.; Denov, M.S. A multidimensional model of resilience: Family, community, national, global and intergenerational resilience. Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 119, 105035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, T.S.; Khan, K.T. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2008, 20, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Narayan, A.J. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience of children in disasters: A multisystem perspective. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.A.; Calam, R.; El-khani, A. Protective factors in the face of political violence: The role of caregiver resilience and parenting styles in Palestine. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2021, 27, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M.; Garbi, L.; Rich, Y. Children’s resilience to ongoing border attacks: The role of father, mother, and child resources. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 54, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A. The centrality of the school in a community during war and conflict. In Helping Children Cope with Trauma: Individual Family and Community Perspectives; Pat-Horenczyk, R., Brom, D., Vogel, J.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, V.; Heath, M.A.; Gibb, G.S.; Coyne, S.; Hudnall, G.; Bledsoe, C. Secondary teachers’ perceptions of their role in suicide prevention and intervention. School Ment. Health 2017, 9, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D.L.; Koomen, H.M.; Spilt, J.L.; Oort, F.J. The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslander, V.; Holzberger, D.; Ofstad, S.B.; Fischbach, A.; Scherer, R. Teacher–student relationships and student outcomes: A systematic second-order meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2025, 151, 365–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.; Kosty, D.; Hauser-McLean, K. Social support and attachment to teachers: Relative importance and specificity among low-income children and youth of color. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016, 34, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, K.; Koomen, H.M. Teacher–child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2012, 14, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M.; Mikulincer, M. Children’s appraisal of teacher as a secure base and their socio-emotional and academic adjustment in middle childhood. Res. Educ. 2006, 75, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zionts, L.T. Examining relationships between students and teachers: A potential extension of attachment theory. In Attachment in Middle Childhood; Kerns, K., Contreras, J.M., Neal-Barnett, A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yagon, M. Adolescents with learning disabilities: Socioemotional and behavioral functioning and attachment relationships with fathers, mothers, and teachers. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1294–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshin, U.; Kleinerman, I.B.; Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M. Teachers’ attachment orientations and children’s school adjustment: Evidence from a longitudinal study of first graders. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M. Perceived close relationships with parents, teachers, and peers: Predictors of social, emotional, and behavioral features in adolescents with LD or comorbid LD and ADHD. J. Learn. Disabil. 2016, 49, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfving–Gupta, S.; Lindblad, F.; Stickley, A.; Schwab-Stone, M.; Ruchkin, V. Community violence exposure and severeposttraumatic stress in suburban American youth: Risk and protective factors. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshem, B.; Haj-Yahia, M.M.; Guterman, N.B. The Role of family and teacher support in post-traumatic stress symptoms among Palestinian adolescents exposed to community violence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablon, Y.B. Positive school climate as a resilience factor in armed conflict zones. Psychol. Violence 2015, 5, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolmer, L.; Hamiel, D.; Margalit, N.; Versano-Eisman, T.; Findler, Y.; Laor, N.; Slone, M. Enhancing children’s resilience in schools to confront trauma: The impact on teachers. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2016, 53, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khodary, B.; Samara, M. Effectiveness of a school-based intervention on the students’ mental health after exposure to war-related trauma. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S.; Ayuob, W. Teachers’ sense of meaning associations with teacher performance and graduates’ resilience: A study of schools serving students of low socio-economic status. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, S.; Morris, R.; Gunnell, D.; Ford, T.; Hollingworth, W.; Tilling, K.; Evans, R.H.; Bell, S.; Grey, J.; Brockmen, R.; et al. Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students ’ mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilz, L.; Fischer, S.M.; Hoppe-Herfurth, A.C.; John, N.A. Consequential partnership the association between teachers’ well-being and students’ well-being and the role of teacher support as a Mediator. Z Psychol. 2022, 230, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A. Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 159, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, K.; Petrovic, L.; Baker, C.; Overstreet, S. An examination of the associations among teacher secondary traumatic stress, teacher—Student relationship quality, and student socio-emotional functioning. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.S.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Roeser, R.W. Effects of teachers’ emotion regulation, burnout, and life satisfaction on student well-being. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle while you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. J. Manage 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Biopsychosoc. Sci. Med. 2008, 70, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.; Bassett, S.M.; Boughton, S.W.; Schuette, S.A.; Shiu, E.W.; Moskowitz, J.T. Psychological well-being and physical health: Associations, mechanisms, and future directions. Emot. Rev. 2018, 10, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, S.; Teucher, B.; Kaaks, R.; Boeing, H.; Vigl, M. Life satisfaction and risk of chronic diseases in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-Germany study. PLoS ONE 2013, 20, e73462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haar, J.M.; Roche, M.A. Family supportive organization perceptions and employee outcomes: The mediating effects of life satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D. Which is a better predictor of job performance: Job satisfaction or life satisfaction? J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2006, 8, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, J.C.; Rehg, M.T.; Near, J.P.; Underhill, J.R. The effect of work/family conflict on intention to quit: The mediating roles of job and life satisfaction. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, M.; Lucas, R.E.; Eid, M.; Diener, E. The prospective effect of life satisfaction on life events. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2012, 4, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Diener, E. Types of subjective well-being and their associations with relationship outcomes. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2019, 3, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A.D.; Huebner, E.S.; Malone, P.S.; Valois, R.F. Life satisfaction and student engagement in adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S.; Thalji, A.; Ferron, J. Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. J. Posit. Psychol. 2011, 6, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.C.; Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Lopez, S.J. The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S.M.; Huebner, E.S. Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? Sch. Psychol. Q. 2004, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.C. Psychological strengths in childhood as predictors of longitudinal outcomes. Sch. Ment. Health. 2016, 8, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D.; Seligman, M.E.P. Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zee, M.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, A.M.; Amo, L.C.; Shanahan, M.E. Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multivariate meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 26, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yin, H.; Lv, L. Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Motivated for teaching? Associations with school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 67, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, L.; Buettner, C.K.; Grant, A.A. Early childhood teachers’ psychological well-being: Exploring potential predictors of depression, stress, and emotional exhaustion. Early Educ. Dev. 2018, 29, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. The role of self-efficacy in job satisfaction, organizational commitment, motivation and job involvement. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2020, 20, 205–224. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ejer/issue/52308/686061 (accessed on 5 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J. The relationship between teacher self-concept, teacher efficacy and burnout. Teach. Teach. 2018, 24, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris-Rothschild, B.K.; Brassard, M.R. Teachers’ conflict management styles: The role of attachment styles and classroom management efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almog, O.; Shechtman, Z. Teachers’ democratic and efficacy beliefs and styles of coping with behavioural problems of pupils with special needs. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2007, 22, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Keren, M.; Godeano-Barr, S.; Levinas, S. Mind the conflict: Empathy when coping with conflicts in the education sphere. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2013395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Prestele, E. Teacher self-efficacy and self-reported cognitive activation and classroom management: A multilevel perspective on the role of school characteristics. Learn. Instr. 2021, 76, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajovsky, D.B.; Chesnut, S.R.; Jensen, K.M. The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 82, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Connor, C.M.; Yang, Y.; Roehrig, A.D.; Morrison, F.J. The effects of teacher qualification, teacher self-efficacy, and classroom practices on fifth graders’ literacy outcomes. Elem. Sch. J. 2012, 113, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimmieson, N.L.; Hannam, R.L.; Yeo, G.B. Teacher organizational citizenship behaviours and job efficacy: Implications for student quality of school life. Br. J. Psychol. 2010, 101, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feniger, Y.; Bar-Haim, E.; Blank, C. From social origin to selective high school courses: Ability grouping as a mechanism of securing social advantage in Israeli secondary education. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2021, 76, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemi, A.; Madjar, N.; Daumiller, M.; Rich, Y. Achievement goals of the social peer-group and the entire class: Relationships with students’ individual achievement goals. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2024, 115, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, A. Homeroom teachers’ professional judgments: Analysis of considerations, justifications, and structure. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2025, 159, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutov, L.; Hazan, O. Mishimot ve-yachasim shel mechanchim: Heqer mikreh be-veit sefer ezori makif. Rav Gavanim 2014, 14, 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Weissblai, E. Hinukh kitah be-ma’arechet ha-hinukh be-Yisrael; Knesset Research and Information Center: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023. Available online: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/bb8f7a26-680f-ee11-815c-005056aa4246/2_bb8f7a26-680f-ee11-815c-005056aa4246_11_20237.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Tezanos-Pinto, D.; Mazziotta, A.; Feuchte, F. Intergroup contact and reconciliation among Liberian refugees: A multilevel analysis in a multiple groups setting. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2017, 23, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Shoshani, A.; Roth, G. Conditional regard in the classroom: A double-edged sword. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 621046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C. Contextualizing context in organizational research. In The Handbook of Multilevel Theory, Measurement, and Analysis; Humphrey, S.E., LeBreton, J.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Teaching Staff in the Education System. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/Pages/2023/%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%91%D7%93%D7%99-%D7%94%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%94-%D7%91%D7%9E%D7%A2%D7%A8%D7%9B%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%97%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%9A.aspx (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Slone, M. Growing up in Israel: Lessons on understanding the effects of political violence on children. In Adolescents and War: How Youth Deal with Political Violence; Barber, B.K., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, I.; Slone, M. Resilience and political violence: A cross-cultural study of moderating effects among jewish- and arab-israeli youth. Youth Soc. 2011, 43, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, M.; Adiri, M.; Arian, A. Adverse political events and psychological adjustment: Two cross-cultural studies. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 37, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Spencer, P.M. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual; Clinical Psychometric Research: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, M.; Zebrack, B.J.; Meeske, K.A.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Block, R.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Li, Y.; Butler, M.; Cole, S. Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: A 1-year longitudinal study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2160–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slone, M.; Shoshani, A.; Paltieli, T. Psychological consequences of forced evacuation on children: Risk and protective factors. J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Johnson, K.M.; Feeny, N.C.; Treadwell, K.R.H. The child PTSD symptom scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2001, 30, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E.B.; Asnaani, A.; Zang, Y.; Capaldi, S.; Yeh, R. Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 47, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.; Larsen, J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, I.A.; Kass, E. Teacher self-efficacy: A classroom-organization conceptualization. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–90. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.L.; Graham, J.W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, A.; Solomon, Z. Gender differences in PTSD in Israeli youth exposed to terror attacks. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even-Chen, M.S.; Irzhaky, H. Exposure to terrorism and violent behavior among adolescents in Israel. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbe, E.; Aelterman, A. Gender in teaching: A literature review. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2007, 13, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, K.S.; Miller, K.F.; McKenzie, R.; Epstein, A. Where low and high inference data converge: Validation of CLASS assessment of mathematics instruction using mobile eye tracking with expert and novice teachers. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2015, 13, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.J.; White, S.L.J.; Cologon, K.; Pianta, R.C. Do teachers’ years of experience make a difference in the quality of teaching? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 96, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.P.; Nelson, L.D.; Simonsohn, U. False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. In Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khodary, B.; Samara, M.; Askew, C. Traumatic events and PTSD among Palestinian children and adolescents: The effect of demographic and socioeconomic factors. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, E.G.; Fayyad, J.A.; Farhat, C.; Pluess, M.; Haddad, Y.C.; Tabet, C.C.; Farah, L.; Kessler, R.C. Role of childhood adversities and environmental sensitivity in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in war-exposed Syrian refugee children and adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.D.; Ajeeb, M.; Fadel, L.; Saleh, G. Mental health in Syrian children with a focus on post-traumatic stress: A cross-sectional study from Syrian schools. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huesmann, L.R.; Dubow, E.F.; Boxer, P.; Landau, S.F.; Gvirsman, S.D.; Shikaki, K. Children’s exposure to violent political conflict stimulates aggression at peers by increasing emotional distress, aggressive script rehearsal, and normative beliefs favoring aggression. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, S.; Guvenmez, O. Psychiatric symptoms in traumatized Syrian refugee children settled in Hatay. Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2020, 74, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, R.; Baum, N. Intervention in a shared traumatic reality: A new challenge for social workers. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.L. The Measurement of Personality Traits by Scales and Inventories; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.N.; Messick, S. Response styles and the assessment of psychopathology. In Measurement in Personality and Cognition; Vandenberg, S.G., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962; pp. 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; French, D.C. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zee, M.; Koomen, H.M.; Roorda, D.L. Understanding cross-cultural differences in affective teacher-student relationships: A comparison between Dutch and Chinese primary school teachers and students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 76, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.M.; Chow, B.W.; McBride, C.; Mol, S.T. Students’ sense of belonging at school in 41 countries: Cross-cultural variability. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2016, 47, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M.A.; Lin, S.; Longobardi, C. A cross-cultural comparison of teacher-student relationship quality in Chinese and Italian teachers and students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 99, 101227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, E.S.; Frazier, S.L.; Maríñez-Lora, A.M.; Lakind, D.; Atkins, M.S.; Jakobsons, L.; Hamre, B.K.; Bhaumik, D.K.; Parker-Katz, M.; Neal, J.W.; et al. Expanding the role of school psychologists to support early career teachers: A mixed-method study. School Psych. Rev. 2016, 45, 226–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Schoch, S.; Scholz, U.; Rackow, P. Satisfaction: The mediating role of job demands and job resources. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 25, 1545–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentsch, A.; Hoferichter, F.; Blömeke, S.; König, J.; Kaiser, G. Investigating teachers’ job satisfaction, stress and working environment: The roles of self-efficacy and school leadership. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 60, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-class level | |||||||||||

| 1. Student PLE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Student general distress | 0.33 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Student anxiety | 0.35 *** | 0.94 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Student depression | 0.24 *** | 0.89 *** | 0.78 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Student somatization | 0.31 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.68 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Student PTS symptoms | 0.49 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.58 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Student gender | 0.17 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.22 *** | – | – | – | – | – |

| M | 16.57 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 14.64 | |||||

| SD | 10.64 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 13.03 | |||||

| Between-class level | |||||||||||

| 1. Student PLE | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Student general distress | 0.28 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Student anxiety | 0.38 *** | 0.93 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Student depression | 0.19 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.79 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Student somatization | 0.15 *** | 0.87 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.67 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Student PTS symptoms | 0.65 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.58 *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Teacher SWLS | 0.02 | −0.28 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.23 *** | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Teacher class efficacy | −0.05 * | −0.26 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.10 *** | 0.20 *** | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Teacher school efficacy | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.08 *** | 0.002 | −0.008 | −0.08 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.31 *** | – | – | – |

| 10. Grade level | 0.13 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.34 *** | −0.011 | −0.01 | 0.06 * | −0.17 *** | −0.11 *** | – | – |

| 11. Teacher gender | −0.09 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.16 *** | −0.23 *** | 0.001 | −0.07 ** | 0.01 | 0.15 *** | 0.01 | −0.25 *** | – |

| 12. Teacher seniority | −0.08 ** | −0.23 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.08 ** | −0.18 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.21 *** | −0.18 *** | 0.39 *** |

| M | 16.57 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 14.64 | 26.64 | 4.63 | 4.40 | ||

| SD | 6.84 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 3.87 | 5.27 | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| Student General Distress | Student Anxiety | Student Depression | Student Somatization | Student PTS Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-class effect | |||||

| PLE | 0.026 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.608 *** |

| Between-class effect | |||||

| PLE | 0.009 * | 0.014 ** | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.382 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shur-Kraspin, L.; Slone, M.; Kanat-Maymon, Y. Youth Exposed to Armed Conflict: The Homeroom Teacher as a Protective Agent Promoting Student Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081233

Shur-Kraspin L, Slone M, Kanat-Maymon Y. Youth Exposed to Armed Conflict: The Homeroom Teacher as a Protective Agent Promoting Student Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081233

Chicago/Turabian StyleShur-Kraspin, Lia, Michelle Slone, and Yaniv Kanat-Maymon. 2025. "Youth Exposed to Armed Conflict: The Homeroom Teacher as a Protective Agent Promoting Student Resilience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081233

APA StyleShur-Kraspin, L., Slone, M., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2025). Youth Exposed to Armed Conflict: The Homeroom Teacher as a Protective Agent Promoting Student Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081233