Comprehensive Communication for a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care: A Framework for Enhancing Health Communication Messages for People Living with HIV

Abstract

1. Introduction

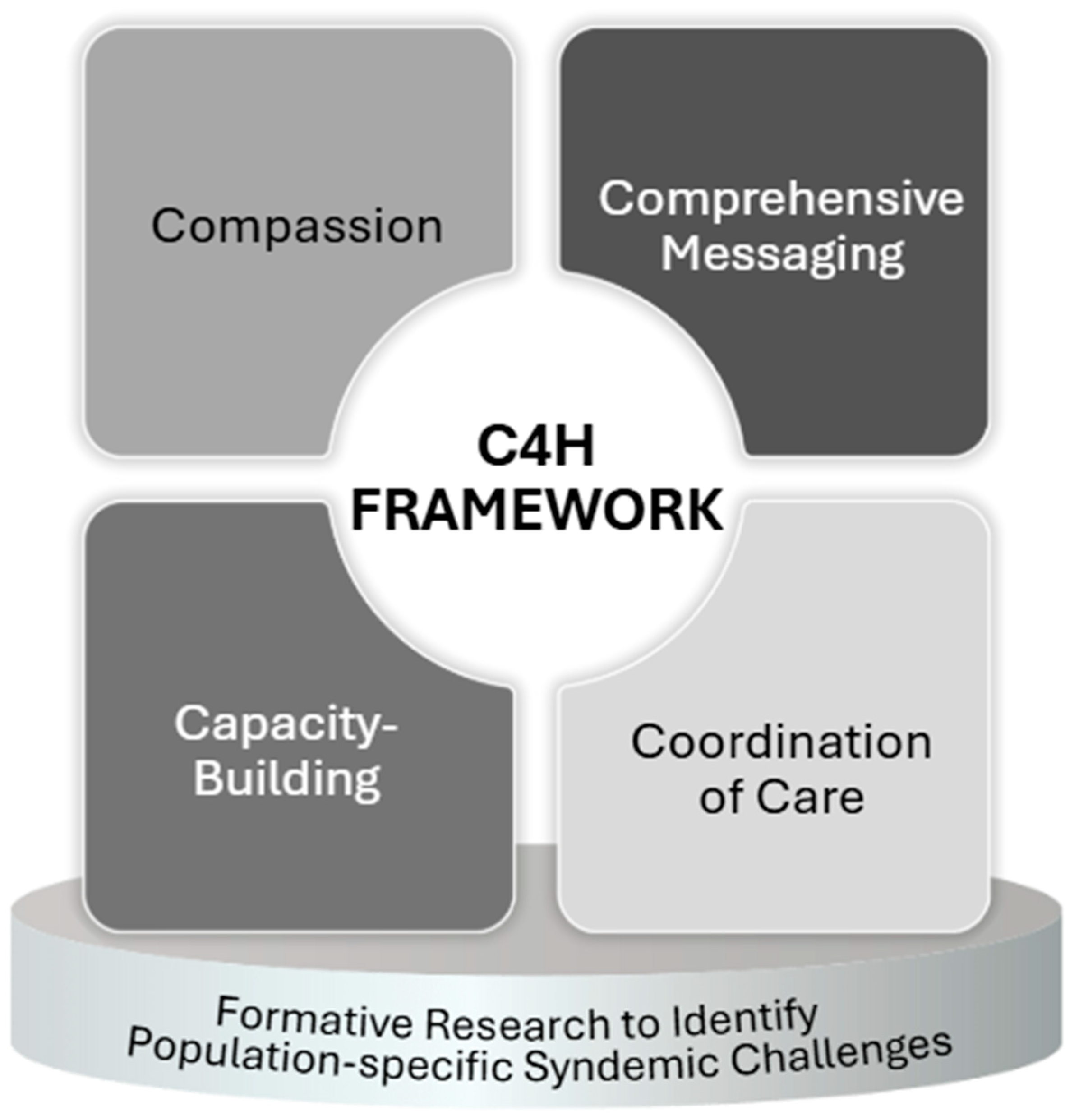

2. Developing Health Communication Messages to Support a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care

3. Contextualizing the C4H Framework: Formative Research to Identify Population-Specific Challenges Within a Syndemic

Directions for Future Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Literature Review Methods

References

- Singer, M. Aids and the health crisis of the us urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 39, 931–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the sava syndemic. Free Inq. Creat. Sociol. 1996, 24, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski, B.; Garofalo, R.; Herrick, A.; Donenberg, G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 34, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of HIV Prevention Strategic Plan Supplement: An Overview of Refreshed Priorities for 2022–2025. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/media/pdfs/cdc-hiv-dhap-external-strategic-plan-2022.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Singer, M.; Bulled, N.; Ostrach, B.; Mendenhall, E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet 2017, 389, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C. Syndemics: A theory in search of data or data in search of a theory? Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 206, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, D.; Levy, J. Addressing the HIV syndemic: A structural and environmental approach. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2018, 21, e25259. [Google Scholar]

- Operario, D.; Nemoto, T. Hiv in transgender communities: Syndemic dynamics and a need for multicomponent interventions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 55 (Suppl. S2), S91–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Operario, D.; Sun, S.; Bermudez, A.N.; Masa, R.; Shangani, S.; van der Elst, E.; Sanders, E. Integrating HIV and mental health interventions to address a global syndemic among men who have sex with men. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e574–e584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Bulled, N.; Ostrach, B. Whither syndemics?: Trends in syndemics research, a review 2015–2019. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrapani, V.; Kaur, M.; Tsai, A.C.; Newman, P.A.; Kumar, R. The impact of a syndemic theory-based intervention on HIV transmission risk behaviour among men who have sex with men in india: Pretest-posttest non-equivalent comparison group trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 295, 112817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L.; Stoicescu, C.; Goddard-Eckrich, D.; Dasgupta, A.; Richer, A.; Benjamin, S.N.; Wu, E.; El-Bassel, N. Intervening on the intersecting issues of intimate partner violence, substance use, and HIV: A review of social intervention group’s (sig) syndemic-focused interventions for women. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2023, 33, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Gruenewald, T.L.; Kemeny, M.E. When the social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1191–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelder, A.W.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Jain, J.; Cohn, M.; Earle, M.A.; Carrico, A.W. A novel technology-enhanced internalized stigma and shame intervention for HIV-positive persons with substance use disorders. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2020, 27, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attonito, J.; Villalba, K.; Dévieux, J.G. Effectiveness of an intervention for improving treatment adherence, service utilization and viral load among HIV-positive adult alcohol users. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, C.; Comfort, M.; Lopez, A.M.; Kral, A.H.; Murdoch, O.; Lorvick, J. Addressing structural barriers to HIV care among triply diagnosed adults: Project bridge oakland. Health Soc. Work 2017, 42, e53–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudewyns, V.; Uhrig, J.D.; Williams, P.A.; Anderson, S.K.; Stryker, J.E. Message framing strategies to promote the uptake of prep: Results from formative research with diverse adult populations in the united states. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehlman, J.; Uhrig, J.D.; Friedman, A.; Scales, M.; Forsythe, A.; Robinson, S.J. Bundling of stds and HIV in prevention messages. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicago Department of Public Health. HIV-STI Data Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/cdph/HIV_STI/CDPH_HIVSTI_DataReport_09-2022.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Daskalakis, D.; Phillips, H.J. Addressing Monkeypox Holistically. 2022. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240811023646/https://www.hiv.gov/blog/addressing-monkeypox-holistically/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Parsons, J.T.; John, S.A.; Millar, B.M.; Starks, T.J. Testing the efficacy of combined motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills training to reduce methamphetamine use and improve HIV medication adherence among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 2674–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, A.W.; Flentje, A.; Gruber, V.A.; Woods, W.J.; Discepola, M.V.; Dilworth, S.E.; Neilands, T.B.; Jain, J.; Siever, M.D. Community-based harm reduction substance abuse treatment with methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. J. Urban Health 2014, 91, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.B.; Hennessy, M.; Eisenberg, M.M. Increasing quality of life and reducing HIV burden: The path+ intervention. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.K.; Kennard, B.D.; Emslie, G.J.; Mayes, T.L.; Whiteley, L.B.; Bethel, J.; Xu, J.; Thornton, S.; Tanney, M.R.; Hawkins, L.A.; et al. Effective treatment of depressive disorders in medical clinics for adolescents and young adults living with HIV: A controlled trial. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 71, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himelhoch, S.; Medoff, D.; Maxfield, J.; Dihmes, S.; Dixon, L.; Robinson, C.; Potts, W.; Mohr, D.C. Telephone based cognitive behavioral therapy targeting major depression among urban dwelling, low income people living with HIV/AIDS: Results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, J.M.; Wiebe, J.S.; Sauceda, J.A.; Huh, D.; Sanchez, G.; Longoria, V.; Bedoya, C.A.; Safren, S.A. A preliminary rct of cbt-ad for adherence and depression among HIV-positive latinos on the U.S.-Mexico border: The nuevo día study. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 2816–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiksin, R.; Melendez-Torres, G.; Falconer, J.; Witzel, T.C.; Weatherburn, P.; Bonell, C. Theories of change for e-health interventions targeting HIV/STIs and sexual risk, substance use and mental ill health amongst men who have sex with men: Systematic review and synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S.R.; Warren, R.; Shedlin, M.; Melkus, G.; Kershaw, T.; Vorderstrasse, A. A framework for using ehealth interventions to overcome medical mistrust among sexual minority men of color living with chronic conditions. Behav. Med. 2019, 45, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, G.A.O.; Fletcher, J.B.; Young, L.E.; Klausner, J.D. Virtual avatars as a new tool for human immunodeficiency virus prevention among men who have sex with men: A narrative review. Mhealth 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, I.B.; Howell, K.H.; Kamody, R.C.; Maclin-Akinyemi, C.; Mandell, J. Resilience as a moderator between syndemics and depression in mothers living with HIV. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Martinez, J.; Tamargo, J.A.; Delgado-Enciso, I.; Liu, Q.; Acuña, L.; Laverde, E.; Barbieri, M.A.; Trepka, M.J.; Campa, A.; Siminski, S.; et al. Resilience, anxiety, stress, and substance use patterns during COVID-19 pandemic in the miami adult studies on HIV (mash) cohort. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.C.; Threats, M.; Blackburn, N.A.; LeGrand, S.; Dong, W.; Pulley, D.V.; Sallabank, G.; Harper, G.W.; Hightow-Weidman, L.B.; Bauermeister, J.A. ”Stay strong! Keep ya head up! Move on! It gets better!!!!”: Resilience processes in the healthmpowerment online intervention of young black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Care 2018, 30, S27–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connecticut Department of Public Health. Ending the Syndemic. 2021. Available online: https://endthesyndemicct.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Handford, C.D.; ATynan, M.; Agha, A.; Rzeznikiewiz, D.; Glazier, R.H. Organization of care for persons with HIV-infection: A systematic review. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.O.; Sohler, N.L.; Cooperman, N.A.; Berg, K.M.; Litwin, A.H.; Arnsten, J.H. Strategies to improve access to and utilization of health care services and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users. Subst. Use Misuse 2011, 46, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, K.; Lentz, C.; Boccher-Lattimore, D.; Cournos, F.; Pather, A.; Sukumaran, S.; Remien, R.H.; Mellins, C.A. Interventions for integrating behavioral health into HIV settings for us adults: A narrative review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 2010–2020. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIV.gov. Find HIV Services near You. Available online: https://locator.hiv.gov/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Let’s Stop HIV Together. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/stophivtogether/index.html (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Aidala, A.; Cross, J.E.; Stall, R.; Harre, D.; Sumartojo, E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: Implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav. 2005, 9, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.H.; Bradford, J.B.; Mimiaga, M.J.; Boswell, S.L. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet 2016, 388, 1194–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, S.; Sifakis, F.; Cleghorn, F.; Beyrer, C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Grebler, T.; Amaral, C.M.; McKerney, M.; White, D.; Kalichman, M.O.; Cherry, C.; Eaton, L. Food insecurity and antiretroviral adherence among HIV positive adults who drink alcohol. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brown, S.E.; Krishnan, A.; Ranjit, Y.S.; Marcus, R.; Altice, F.L. Assessing mobile health feasibility and acceptability among HIV-infected cocaine users and their healthcare providers: Guidance for implementing an intervention. Mhealth 2020, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.; Moody-Thomas, S.; Gruber, D. Patient perspectives on tobacco cessation services for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabiun, S.; Shoveller, J.; Moore, D.; Buxton, J.; Goldenberg, S.M. A systematic review of qualitative studies examining the experiences of people living with HIV accessing care in the era of antiretroviral therapy: Navigating the complexities of care. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 977–989. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, N.A.; Mayo, D.; Safren, S.A. Interventions addressing depression and HIV-related outcomes in people with HIV. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021, 18, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, A.W.; Zepf, R.; Meanley, S.; Batchelder, A.; Stall, R. Critical review: When the party is over: A systematic review of behavioral interventions for substance-using men who have sex with men. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 73, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalone, D.W.; Nelson, K.M.; Batchelder, A.W.; Chiu, C.; Gunn, H.A.; Horvath, K.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of combination behavioral interventions co-targeting psychosocial syndemics and HIV-related health behaviors for sexual minority men. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 681–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.L.; Vogel, A.L.; Huang, G.C.; Serrano, K.J.; Rice, E.L.; Tsakraklides, S.P.; Fiore, S.M. The science of team science: A review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Kohrt, B.A. Syndemics of HIV with mental illness and other noncommunicable diseases: A research agenda to address the gap between syndemic theory and current research practice. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2020, 15, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas-Vail, M.B. Syndemics theory and its applications to HIV/AIDS public health interventions. Int. J. Med. Sociol. Anthropol. 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| Example Message | Framework Alignment |

|---|---|

| “You have the power to navigate challenges and create positive change. Commit to your HIV care journey by addressing barriers head-on and finding strategies to overcome them. Your dedication to staying in care, managing any substance use, and nurturing your mental health can improve your overall health. A case manager can connect you with other support, such as housing, transportation, health services, health insurance coverage, and substance use disorder treatment. In most cases, HIV treatment is free! Find services near you. [Link to services.]” | Capacity-building Compassion Comprehensive messaging Coordination of care |

| “Life can be challenging, and daily chaos can often distract us from focusing on our health and well-being. You have the power to navigate these challenges. Make a plan to prioritize your HIV treatment, work on managing any substance use, and nurture your well-being to improve your overall health. Find a provider in your community who can support you on your journey. [Link to providers.]” | Capacity-building Compassion Coordination of care |

| “Choose progress over perfection. Build positive relationships and surround yourself with a supportive community. Take charge of your well-being, align your choices with your goals, manage any substance use, and prioritize your HIV treatment. Small changes can have a big impact on your health and well-being. Find services in your community. [Link to services.]” | Capacity-building Comprehensive messaging Coordination of Care |

| “You possess inner strength and resilience. Celebrate progress along your journey. By taking care of your mental health, you make it easier to manage your HIV.” | Capacity-building Compassion Comprehensive messaging |

| “Life’s challenges can sometimes get in the way of HIV care. But you are stronger than your challenges. You may face roadblocks, but you can always find an alternate route. Help is there. You can do this!” | Capacity-building Compassion |

| “Prioritize both your mental well-being and your HIV care. You have the power to keep track of your medications, practice self-care, and foster open communication with your care team.” | Capacity-building Comprehensive messaging |

| “We know it’s not easy, but you deserve support for both HIV and substance use. Treatment can make a difference, and you don’t have to face it alone.” | Compassion Comprehensive messaging |

| “Taking care of your mind is just as important as taking your HIV meds. Both help you stay strong and healthy. Explore free mental health and HIV care resources in your area today! [Link to services.]” | Comprehensive messaging Coordination of care |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheff, S.E.; Boudewyns, V.; Taylor, J.C.; Getachew-Smith, H.; Bhushan, N.L.; Uhrig, J.D. Comprehensive Communication for a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care: A Framework for Enhancing Health Communication Messages for People Living with HIV. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081231

Sheff SE, Boudewyns V, Taylor JC, Getachew-Smith H, Bhushan NL, Uhrig JD. Comprehensive Communication for a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care: A Framework for Enhancing Health Communication Messages for People Living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081231

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheff, Sarah E., Vanessa Boudewyns, Jocelyn Coleman Taylor, Hannah Getachew-Smith, Nivedita L. Bhushan, and Jennifer D. Uhrig. 2025. "Comprehensive Communication for a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care: A Framework for Enhancing Health Communication Messages for People Living with HIV" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081231

APA StyleSheff, S. E., Boudewyns, V., Taylor, J. C., Getachew-Smith, H., Bhushan, N. L., & Uhrig, J. D. (2025). Comprehensive Communication for a Syndemic Approach to HIV Care: A Framework for Enhancing Health Communication Messages for People Living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081231