Attainment of Community-Based Goals Is Associated with Lower Risk of Hospital Readmission for Older Australians Accessing the Australian Transition Care Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

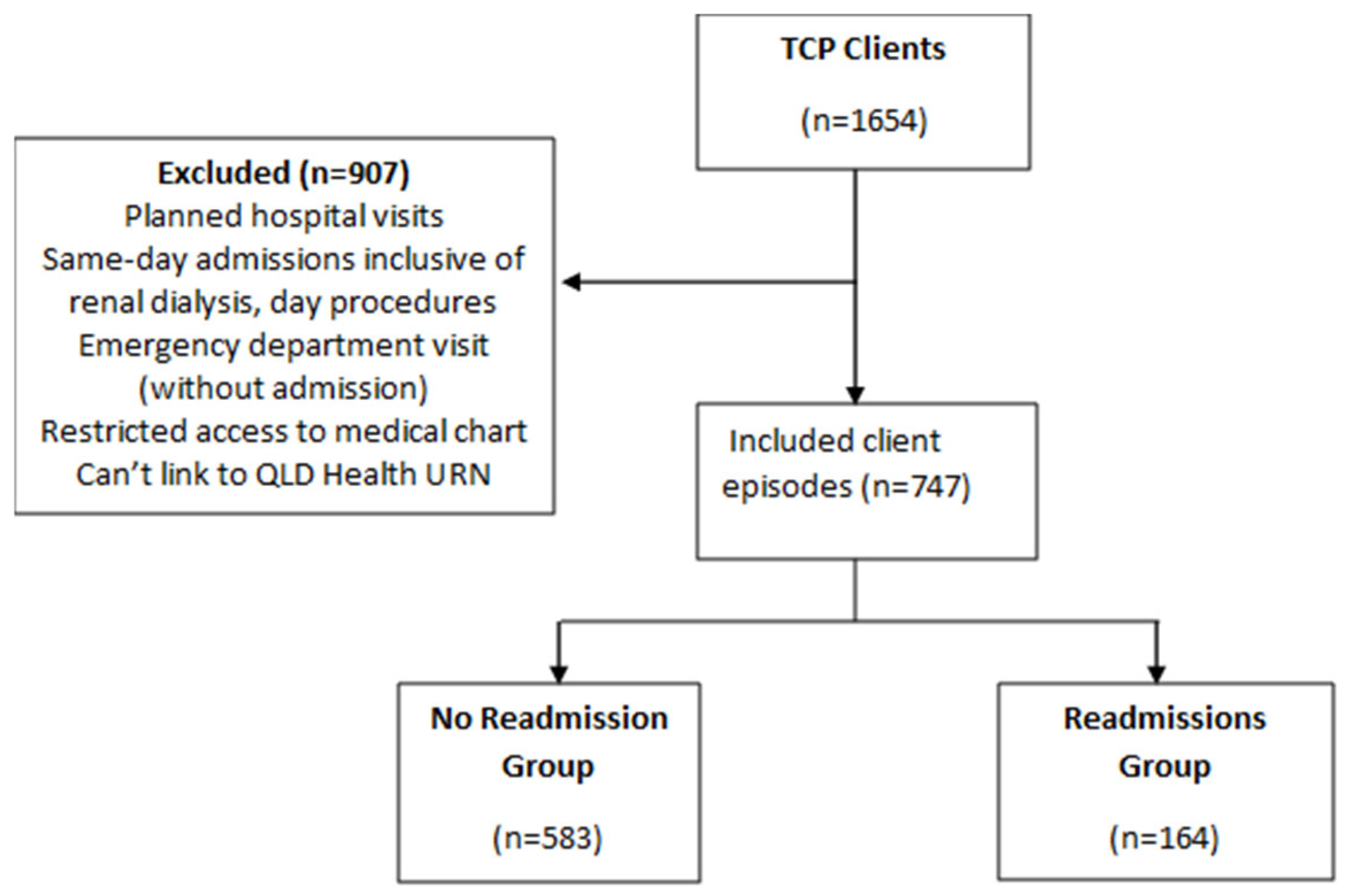

2.3. Participants

2.4. Dataset

Dataset Linking

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Modified Barthel Index

2.5.2. Goals

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Client Characteristics

3.2. Client Goals

3.3. Association Between Community-Goals and Readmission to Hospital

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning |

| ieMR | Integrated electronic Medical Record |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| MBI | Modified Barthel Index |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| RACF | Residential Aged Care Facility |

| TCP | Transition Care Program |

| URN | Unique Record Number |

References

- Australian Government: Department of Health and Aged Care. Transition Care Programme Guidelines: Updated December 2022; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, L.C.; Peel, N.M.; Crotty, M.; Kurrle, S.E.; Giles, L.C.; Cameron, I.D. How effective are programs at managing transition from hospital to home? A case study of the Australian transition care program. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Review of the Transition Care Programme; Department of Health Final Report; KPMG: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, L.F.; Grode, L.B.; Lange, J.; Barat, I.; Gregersen, M. Impact of transitional care interventions on hospital readmissions in older medical patients: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, S.; Halbert, J.; Crotty, M.; Cheney, F. Innovations in Aged Care: What are the first quality reports from the Transition Care Program in Australia telling us? Australas. J. Ageing 2008, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flinders Consulting. National Evaluation of the Transition Care Program: Final Evaluation Report; Department of Health (Australia): Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.R. Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 13, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Twenty Years of Population Change; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, S.A.; Peel, N.M.; Marshall, W. Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework to categorise goals and assess goal attainment for transition care clients. Australas. J. Ageing 2015, 34, E13–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, N.; McCourt, E.; Owen, K.; Salih, S. Differences in Clients Who Develop Home-Based or Community-Based Goals in a Transition Care Program: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2023, 7, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Sohn, M.K.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.-G.; Shin, Y.-I.; Kim, S.-Y.; Oh, G.-J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.-S.; et al. Determining the cut-off score for the Modified Barthel Index and the Modified Rankin Scale for assessment of functional independence and residual disability after stroke. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Aito, S.; Atkins, M.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Charlifue, S.; Curt, A.; Ditunno, J.; Glass, C.; Marino, R.; Marshall, R.; et al. Functional recovery measures for spinal cord injury: An evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2008, 31, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraola, A.B.; Sánchez, R.Á.; Hors-Fraile, S.; Petsani, D.; Timoleon, M.; Díaz-Orueta, U.; Carroll, J.; Hopper, L.; Epelde, G.; Kerexeta, J.; et al. User Centered Virtual Coaching for Older Adults at Home Using SMART Goal Plans and I-Change Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.; Seshan, V.E.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Gönen, M. Inference for the difference in the area under the ROC curve derived from nested binary regression models. Biostatistics 2017, 18, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Almirall-Sánchez, A.; Mockler, D.; Adrion, E.; Domínguez-Vivero, C.; Romero-Ortuño, R. Hospital-associated deconditioning: Not only physical, but also cognitive. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.A.; Peel, N.M.; Enright, D.; Marshall, W. Physical Activity Levels of Older Persons Admitted to Transitional Care Programs: An Accelerometer-Based Study. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2019, 2, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodulin, K.; Anderssen, S. Physical activity: Associations with health and summary of guidelines. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Craig, C.L.; Brown, W.J.; Clemes, S.A.; De Cocker, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Hatano, Y.; Inoue, S.; Matsudo, S.M.; Mutrie, N.; et al. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.L.; Hu, W.; Rangarajan, S.; Gasevic, D.; Leong, D.; Iqbal, R.; Casanova, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Anjana, R.M.; Kumar, R.; et al. The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: The PURE study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2643–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’COnnor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.; Hill, K.; Hunt, S.; Haralambous, B. Physical activity recommendations for older Australians. Australas. J. Ageing 2010, 29, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Farrier, K.; Galvin, R.; Johnson, S.; Horgan, N.F.; Warters, A.; Hill, K.D. Physical activity programs for older people in the community receiving home care services: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1045–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.N.; Fields, S.M. Changes in older adults’ impairment, activity, participation and wellbeing as measured by the AusTOMs following participation in a Transition Care Program. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2020, 67, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Moxley, J.H.; Rogers, W.A. Social Support, Isolation, Loneliness, and Health Among Older Adults in the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 728658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B.; Brayne, C. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Peprah, P.; Abass, K.; Siaw, L.P.; Adjakloe, Y.D.A.; Garsonu, E.K.; Phillips, D.R. Loneliness and physical function impairment: Perceived health status as an effect modifier in community-dwelling older adults in Ghana. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuska, K.; Giles-Heinz, A.; Flinn, N.; Neighbor, M.; Bass-Haugen, J. Outcomes of a pilot occupational therapy wellness program for older adults. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2003, 57, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.; Lewis, L.K.; Barr, C.; Maeder, A.; George, S. Community participation of community dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’sUllivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Tittlemier, B.J.; Tiwari, K.K.; Loewen, H. Interprofessional Teams Supporting Care Transitions from Hospital to Community: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total N = 747 Episodes | No Readmission N = 583 | Readmission N = 164 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (SD) | 80.3 (8.1) | 80.4 (8.2) | 80.03 (7.8) | 0.560 |

| Hospital Days LOS; mean (SD) | 31.2 (28.9) | 30.6 (29.7) | 33.4 (26.2) | 0.280 |

| TCP Days LOS; mean (SD) | 57.1 (27.2) | 56.5 (26.5) | 59.1 (29.5) | 0.270 |

| Entry MBI; mean (SD) | 75.5 (15.7) | 75.9 (15.4) | 74.2 (16.9) | 0.230 |

| Exit MBI, mean (SD) | 89.4 (13.4) | 90.5 (11.9) | 85.7 (17.2) | 0.001 |

| Change MBI, mean (SD) | 13.8 (11.6) | 14.4 (11.8) | 11.5 (10.6) | 0.005 |

| Number comorbidities, mean (SD) | 7.2 (2.8) | 7.1 (2.8) | 7.6 (2.8) | 0.050 |

| Male; n (%) | 248 (33.1) | 182 (31.2) | 66 (40.2) | 0.030 |

| Discharge disposition, n (%) | (N = 690) | (N = 533) | (N = 157) | 0.014 |

| Home with no services | 158 (21.2) | 132 (24.7) | 26 (16.5) | |

| Home with services | 496 (66.4) | 379 (71.1) | 117 (74.5) | |

| RACF | 36 (4.8) | 22 (4.1) | 14 (8.9) | |

| Client carer status, n (%) | 0.022 | |||

| Carer | 193 (25.8) | 162 (27.8) | 31 (18.9) | |

| No carer | 554 (74.1) | 421 (72.2) | 133 (81.1) | |

| Primary diagnosis category, n (%) | 0.017 | |||

| Medical | 315 (42.2) | 230 (39.5) | 85 (51.8) | |

| General Surgery | 45 (6.1) | 38 (6.5) | 7 (4.2) | |

| Orthopaedic | 386 (51.7) | 314 (53.9) | 72 (44.0) |

| Goals | Total N = 747 | No Readmission N = 583 | Readmission N = 164 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one goal | 741 | 579 | 162 | 0.300 |

| Number of goals; Mean (SD) | 3.95 (1.6) | 4.03 (1.6) | 3.64 (1.7) | 0.006 |

| Total goals achieved; Mean (SD) | 3.20 (1.7) | 3.39 (1.7) | 2.80 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of home goals; Means (SD) | 2.90 (1.5) | 2.90 (1.5) | 2.70 (1.4) | 0.190 |

| Number home goals achieved; Mean (SD) | 2.50 (1.5) | 2.50 (1.5) | 2.20 (1.6) | 0.021 |

| Number of community goals; Mean (SD) | 1.03 (0.9) | 1.08 (0.9) | 0.80 (0.9) | 0.010 |

| Number of community goals achieved; Mean (SD) | 0.78 (0.8) | 0.83 (0.8) | 0.60 (0.7) | 0.001 |

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of community goals achieved | 0.70 | 0.56 to 0.88 | 0.002 |

| Age on admission | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.01 | 0.342 |

| Female | 0.71 | 0.49 to 1.02 | 0.063 |

| MBI Change | 0.98 | 0.97 to 1.00 | 0.051 |

| Number of home goals achieved | 1.05 | 0.99 to 1.25 | 0.064 |

| Has carer | 0.68 | 0.43 to 1.05 | 0.082 |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.06 | 0.99 to 1.13 | 0.064 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salih, S.A.; Koo, A.; Boland, N.; Reid, N. Attainment of Community-Based Goals Is Associated with Lower Risk of Hospital Readmission for Older Australians Accessing the Australian Transition Care Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081162

Salih SA, Koo A, Boland N, Reid N. Attainment of Community-Based Goals Is Associated with Lower Risk of Hospital Readmission for Older Australians Accessing the Australian Transition Care Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081162

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalih, Salih A., Andrew Koo, Niamh Boland, and Natasha Reid. 2025. "Attainment of Community-Based Goals Is Associated with Lower Risk of Hospital Readmission for Older Australians Accessing the Australian Transition Care Program" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081162

APA StyleSalih, S. A., Koo, A., Boland, N., & Reid, N. (2025). Attainment of Community-Based Goals Is Associated with Lower Risk of Hospital Readmission for Older Australians Accessing the Australian Transition Care Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081162