Readiness Assessment of Healthcare Professionals to Integrate Mental Health Services into Primary Healthcare of Persons with Skin-Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Burden of Mental Health in Skin-NTDs

1.2. Addressing the Burden of Mental Health in Skin-NTD: Integrated Healthcare

1.3. Readiness of Healthcare Professionals for Integrated Healthcare

1.4. Study Objectives

- Examine the influence of demographic characteristics, previous training on mental health and provision of mental health services on readiness to integrate mental health into primary care for people with skin-NTD.

- Elucidate the relationship between mental health barriers, professional development needs and readiness to integrate mental health into primary care for people with skin-NTD.

- Investigate the mediating role of professional development needs on the relationship between mental health barriers and readiness to integrate mental health into primary care for persons with skin-NTD.

2. Method

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Participants and Sample Size

2.3. Data Collection Measures

2.4. Procedure for Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Demographic Influence on Readiness to Integrate Mental Health into Primary Healthcare

3.3. Correlations Between Study Variables

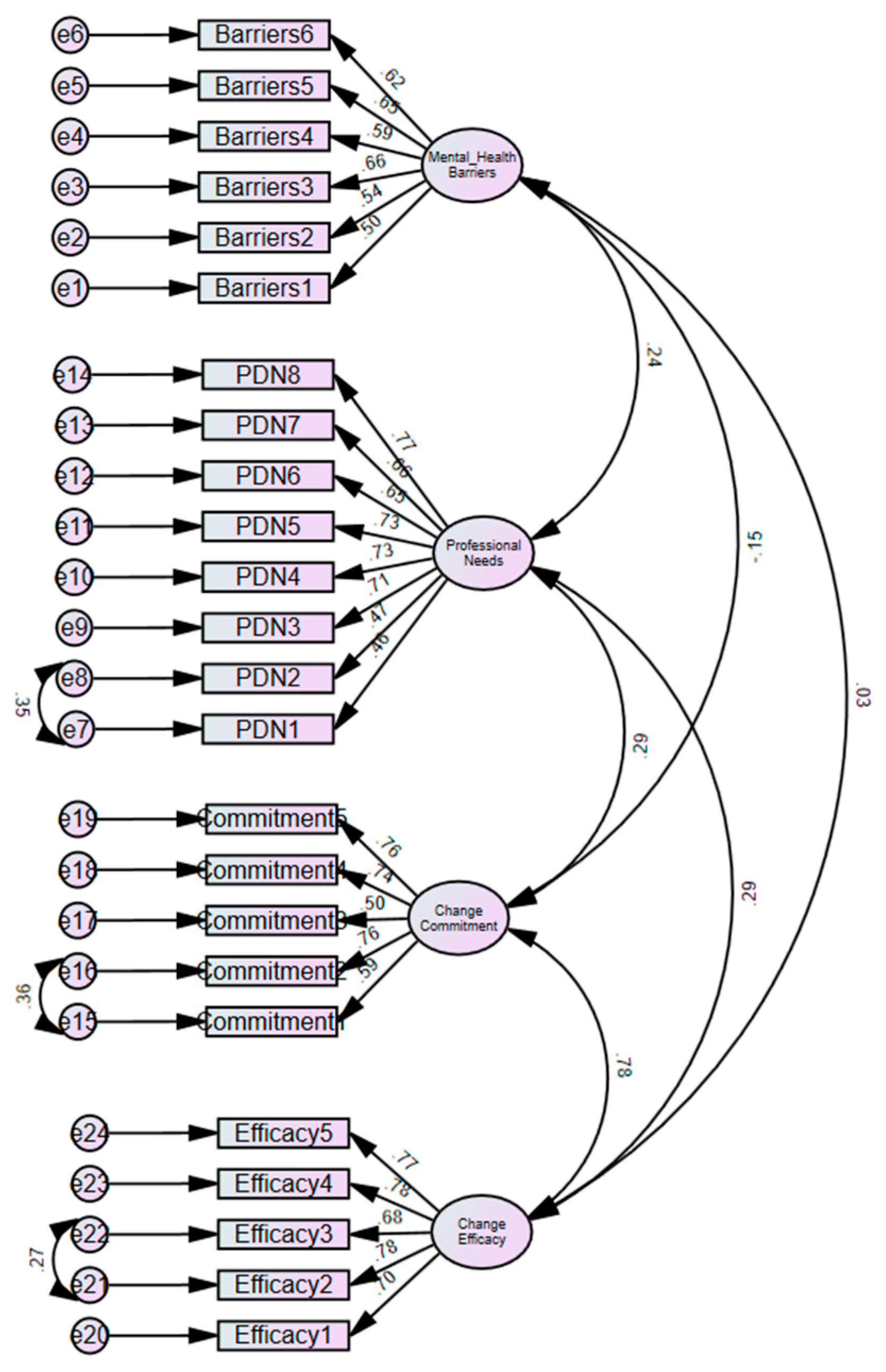

3.4. Confirmatory Factors Analysis (CFA) of Readiness, Barriers and Professional Development Needs

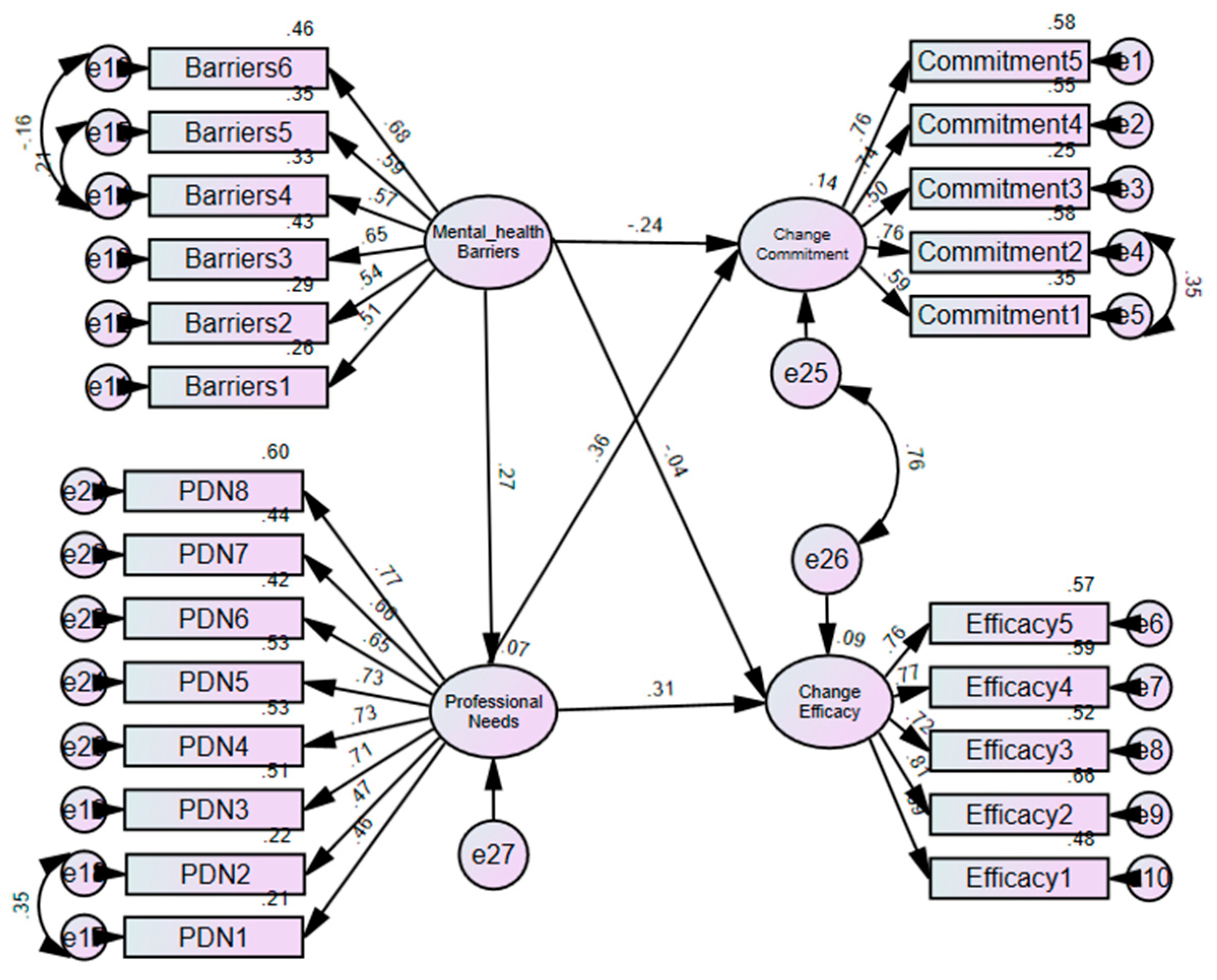

3.5. Relationship Between Readiness, Barriers and Professional Development Needs

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molyneux, D.H.; Savioli, L.; Engels, D. Neglected tropical diseases: Progress towards addressing the chronic pandemic. Lancet 2017, 389, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, F.; Eaton, J.; Jidda, M.; van Brakel, W.H.; Addiss, D.G.; Molyneux, D.H. Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: Progress, partnerships, and integration. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.; Coppleson, D.; Schmied, V. Integrated physical and mental healthcare: An overview of models and their evaluation findings. JBI Evid. Implement. 2020, 18, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akol, A.; Engebretsen, I.M.S.; Skylstad, V.; Nalugya, J.; Ndeezi, G.; Tumwine, J. Health managers’ views on the status of national and decentralized health systems for child and adolescent mental health in Uganda: A qualitative study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.M.; Alvar, J. Stigmatizing neglected tropical diseases: A systematic review. Soc. Med. 2010, 5, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjorlolo, S.; Adimado, E.E.; Setordzi, M.; Akorli, V.V. Prevalence, assessment and correlates of mental health problems in neglected tropical diseases: A systematic review. Int. Health 2024, 16 (Suppl. S1), i12–i21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suma, T.; Shenoy, R.; Kumaraswami, V. A qualitative study of the perceptions, practices and socio-psychological suffering related to chronic brugian filariasis in Kerala, southern India. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2003, 97, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.A.; Mathieu, E.; Addiss, D.G.; Sodahlon, Y.K. A survey of treatment practices and burden of lymphoedema in Togo. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 101, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, E.; Baker, M.C.; Molyneux, D. Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: A perspective on comorbidity. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M.; Wright, B.; Kaye, P.M.; da Conceição, V.; Churchill, R.C. The impact of leishmaniasis on mental health and psychosocial well-being: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, Y.A.; Ackam, N.; Omuojine, J.-P.; Oppong, M.N.; Owusu-Ansah, A.G.; Boateng, H.; Abass, M.K.; Amofa, G.; Ofori, E.; Okyere, P.B.; et al. Mental health and quality of life burden in Buruli ulcer disease patients in Ghana. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, U.M.; Doku, V. Mental health research in Ghana: A literature review. Ghana Med. J. 2012, 46, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.; Mogan, C.; Asare, J.B. An overview of Ghana’s mental health system: Results from an assessment using the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.S.; Sharan, P.; Mirza, I.; Garrido-Cumbrera, M.; Seedat, S.; Mari, J.J.; Sreenivas, V.; Saxena, S. Mental health systems in countries: Where are we now? Lancet 2007, 370, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weobong, B.; Ae-Ngibise, K.A.; Sakyi, L.; Lund, C. Towards implementation of context-specific integrated district mental healthcare plans: A situation analysis of mental health services in five districts in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Redefining Mental Healthcare in Ghana 2022 [cited 2025 17th March 2025]. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/ghana/news/redefining-mental-healthcare-ghana (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Akol, A.; Makumbi, F.; Babirye, J.N.; Nalugya, J.; Nshemereirwe, S.; Engebretsen, I.M.S. Does mhGAP training of primary health care providers improve the identification of child-and adolescent mental, neurological or substance use disorders? Results from a randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Mental Health of People with Neglected Tropical Diseases: Towards a Person-Centred Approach; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, B.A.; Cohen, D.J.; Jetelina, K.K.; Dickinson, L.M.; Davis, M.; Gunn, R.; Gowen, K.; Degruy, F.V.; Miller, B.F.; Green, L.A. Outcomes of integrated behavioral health with primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2017, 30, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonek, J.; Lee, C.-M.; Harrison, A.; Mangurian, C.; Tolou-Shams, M. Key components of effective pediatric integrated mental health care models: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Amick, H.; Lee, S.-Y.D. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: A review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2008, 65, 379–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, C.D.; Li, Y.-F.; Sharp, N.D.; Sales, A.E. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): Development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Lewis, M.A.; Linnan, L.A. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Educ. Res. 2009, 24, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, C.M.; Jacobs, S.R.; Esserman, D.A.; Bruce, K.; Weiner, B.J. Organizational readiness for implementing change: A psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, P.; Allenhof, C.; Pashoja, A.C.; Etzelmueller, A.; Fanaj, N.; Finch, T.; Freund, J.; Hanssen, D.; Mathiasen, K.; Piera-Jiménez, J.; et al. Psychometric properties of two implementation measures: Normalization MeAsure Development questionnaire (NoMAD) and organizational readiness for implementing change (ORIC). Implement. Res. Pract. 2024, 5, 26334895241245448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjorlolo, S.; Aziato, L. Barriers to addressing mental health issues in childbearing women in Ghana. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjorlolo, S.; Aziato, L.; Akorli, V.V. Promoting maternal mental health in Ghana: An examination of the involvement and professional development needs of nurses and midwives. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, M. Structural equation modeling: Threshold criteria for assessing model fit. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Emerald Publishing Limited: England, UK, 2019; pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Badu, E.; O’Brien, A.P.; Mitchell, R. An integrative review of potential enablers and barriers to accessing mental health services in Ghana. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, G.; Basnet, P.; Thapa, B.; Subedi, M. Factors affecting mental health service delivery from primary healthcare facilities of western hilly district of Nepal: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e080163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, O.; Endale, T.; Ryan, G.; Miguel-Esponda, G.; Iyer, S.N.; Eaton, J.; De Silva, M.; Murphy, J. Barriers and drivers to service delivery in global mental health projects. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, K.; Mwangi, F.; Onifade, O.; Abimbola, O.; Jones, F.; Burrows, J.; Lynagh, M.; Majeed, T.; Sharma, D.; Bembridge, E.; et al. Readiness for professional practice among health professions education graduates: A systematic review. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1472834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Timmings, C.; Moore, J.E.; Marquez, C.; Pyka, K.; Gheihman, G.; Straus, S.E. The development of an online decision support tool for organizational readiness for change. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishnavi, V.; Suresh, M. Assessment of healthcare organizational readiness for change: A fuzzy logic approach. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2022, 34, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No | Scales and Their Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Readiness to Implement Change (χ2 (32) = 69.92, p < 0.001; CMIN/df = 2.19; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.06) | ||

| Change Commitment Scale | ||

| 1 | We are committed to implementing this change | 0.57 |

| 2 | We are determined to implement this change. | 0.76 |

| 3 | We are motivated to implement this change. | 0.49 |

| 4 | We will do whatever it takes to implement this change. | 0.74 |

| 5 | We want to implement this change. | 0.77 |

| Change Efficacy Scale | ||

| 1 | We feel confident that they can manage the politics of implementing this change. | 0.69 |

| 2 | We feel confident that the organization can support people as they adjust to this change. | 0.78 |

| 3 | We feel confident that they can coordinate tasks so that implementation goes smoothly. | 0.68 |

| 4 | We feel confident that they can keep track of progress in implementing this change | 0.78 |

| 5 | We feel confident that they can handle the challenges that might arise in implementing this change. | 0.77 |

| Mental Health Barriers Scale (χ2 (8) = 14.82, p = 0.063; CMIN/df = 1.85; TLI = 0.96; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.05) | ||

| …. | ||

| 1 | Heavy workload at the unit/department. | 0.50 |

| 2 | Lack of knowledge about mental health issues. | 0.55 |

| 3 | Lack of measures to detect mental health issues. | 0.67 |

| 4 | Time allocated to see patients is too short. | 0.54 |

| 5 | Lack the skills to start conversation about mental health. | 0.62 |

| 6 | Lack of mental health resources to serve as a guide or reference. | 0.63 |

| Professional Development Needs Scale (χ2 (19) = 25.11, p = 0.157; CMIN/df = 1.32; TLI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03). | ||

| I need education on | ||

| 1 | The relationship between NTD and mental health | 0.46 |

| 2 | Commonly diagnosed mental health conditions in NTDs | 0.47 |

| 3 | Screening and assessment of mental health issues | 0.71 |

| 4 | Relationship building with persons with mental health problems. | 0.73 |

| 5 | Working with families of people with mental health problems. | 0.73 |

| 6 | Provision of low-cost psychosocial interventions | 0.65 |

| 7 | Therapeutic communication | 0.66 |

| 8 | Referring and following up on patients with mental health problems | 0.78 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 133 | 52.8 |

| Female | 119 | 47.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 142 | 56.3 |

| Married | 108 | 42.9 |

| Education attainment | ||

| Certificate | 88 | 34.9 |

| Diploma | 131 | 52 |

| Degree | 33 | 13.1 |

| Participated in Mental health CPD | ||

| Not at all | 118 | 46.8 |

| Only once | 59 | 23.4 |

| 2 to 4 times | 49 | 19.4 |

| ≥5 times | 26 | 10.3 |

| Professional background | ||

| Registered general nurse | 122 | 48.4 |

| Enrolled nurse | 76 | 30.2 |

| Physician assistant | 8 | 3.2 |

| Medical officer | 3 | 1.2 |

| Midwife | 15 | 6 |

| Community health nurse | 13 | 5.2 |

| Other | 15 | 6 |

| Type of health facility | ||

| Hospital | 70 | 27.8 |

| Health center | 83 | 32.9 |

| CHPS compound | 89 | 35.3 |

| Other | 10 | 4 |

| Enquired about mental health | ||

| Not at all | 44 | 17.5 |

| Only once | 84 | 33.3 |

| 2 to 4 times | 73 | 29 |

| ≥5 times | 51 | 20.2 |

| S. No | Strongly Disagree n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Agree n (%) | Strongly Agree n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Barriers Scale | ||||||

| 1 | Heavy workload at the unit/department. | 18 (7.1) | 70 (27.8) | 21(8.3) | 112 (44.4) | 31(12.3) |

| 2 | Lack of knowledge about mental health issues. | 22 (8.7) | 72 (28.6) | 24 (9.5) | 106 (42.1) | 28 (11.1) |

| 3 | Lack of measures to detect mental health issues. | 19 (7.5) | 43 (17.1) | 33 (13.1) | 129 (51.2) | 28 (11.1) |

| 4 | Time allocated to see patients is too short. | 40 (15.9) | 78 (31.0) | 24 (9.5) | 90 (35.7) | 20 (7.9) |

| 5 | Lack the skills to start conversation about mental health. | 29 (11.5) | 74 (29.4) | 20 (7.9) | 111 (44.0) | 18 (7.1) |

| 6 | Lack of mental health resources to serve as a guide or reference. | 12 (4.8) | 28 (11.1) | 12 (4.8) | 116 (46.0) | 84 (33.3) |

| Professional Development Needs Scale | ||||||

| 1 | The relationship between NTD and mental health | 5 (2.0) | 10 (4.0) | 16 (6.3) | 158 (62.7) | 63 (25) |

| 2 | Commonly diagnosed mental health conditions in NTDs | 4 (1.6) | 15 (6.0) | 18 (7.1) | 162 (64.3) | 53 (21.0) |

| 3 | Screening and assessment of mental health issues | 2 (0.8) | 14 (5.6) | 9 (3.6) | 159 (63.1) | 68 (27.0) |

| 4 | Relationship building with persons with mental health problems. | 6 (2.4) | 11 (4.4) | 15 (6.0) | 164 (65.1) | 56 (22.2) |

| 5 | Working with families of people with mental health problems. | 6 (2.4) | 23 (9.1) | 17 (6.7) | 138 (54.8) | 68 (27.0) |

| 6 | Provision of low-cost psychosocial interventions | 3 (1.2) | 11 (4.4) | 20 (7.9) | 147 (58.3) | 71 (28.2) |

| 7 | Therapeutic communication | 5 (2.0) | 16 (6.3) | 15 (6.0) | 141 (56.0) | 75 (29.8) |

| 8 | Referring and following up on patients with mental health problems | 6 (2.4) | 14 (5.6) | 10 (4.0) | 132 (52.4) | 90 (35.7) |

| Commitment | Efficacy | Total Readiness | MHBS | PDNS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness | |||||

| Commitment | 1 | ||||

| Efficacy | 0.63 ** | 1 | |||

| Total Readiness | 0.90 ** | 0.91 ** | 1 | ||

| MHBS | −0.14 * | 0.01 | −0.07 | 1 | |

| PDNS | 0.27 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.18 ** | 1 |

| Years of practice | 0.17 ** | 0.14 * | 0.17 ** | −0.06 | 0.19 ** |

| Mean | 20.36 | 19.94 | 40.29 | 19.73 | 32.34 |

| SD | 2.98 | 3.10 | 5.49 | 4.85 | 4.80 |

| α | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.86 |

| Relationships | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Confidence | Interval | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Barriers → Needs → Change commitment | −0.192 (−2.77) | 0.078 | 0.019 | 0.192 | 0.011 | Partial mediation |

| Barriers → Needs → Change efficacy | −0.043 (−0.549) | 0.084 | 0.017 | 0.208 | 0.009 | Full mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adjorlolo, S.; Junior Osei, S.K.; Adimado, E.E.; Setordzi, M.; Akorli, V.V.; Aprekua, L.O.; Adjorlolo, P.K. Readiness Assessment of Healthcare Professionals to Integrate Mental Health Services into Primary Healthcare of Persons with Skin-Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070991

Adjorlolo S, Junior Osei SK, Adimado EE, Setordzi M, Akorli VV, Aprekua LO, Adjorlolo PK. Readiness Assessment of Healthcare Professionals to Integrate Mental Health Services into Primary Healthcare of Persons with Skin-Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modeling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070991

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdjorlolo, Samuel, Stephanopoulos Kofi Junior Osei, Emma Efua Adimado, Mawuko Setordzi, Vincent Valentine Akorli, Lawrencia Obenewaa Aprekua, and Paul Kwame Adjorlolo. 2025. "Readiness Assessment of Healthcare Professionals to Integrate Mental Health Services into Primary Healthcare of Persons with Skin-Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modeling" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070991

APA StyleAdjorlolo, S., Junior Osei, S. K., Adimado, E. E., Setordzi, M., Akorli, V. V., Aprekua, L. O., & Adjorlolo, P. K. (2025). Readiness Assessment of Healthcare Professionals to Integrate Mental Health Services into Primary Healthcare of Persons with Skin-Neglected Tropical Diseases in Ghana: A Structural Equation Modeling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070991