Awake Bruxism Identification: A Specialized Assessment Tool for Children and Adolescents—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

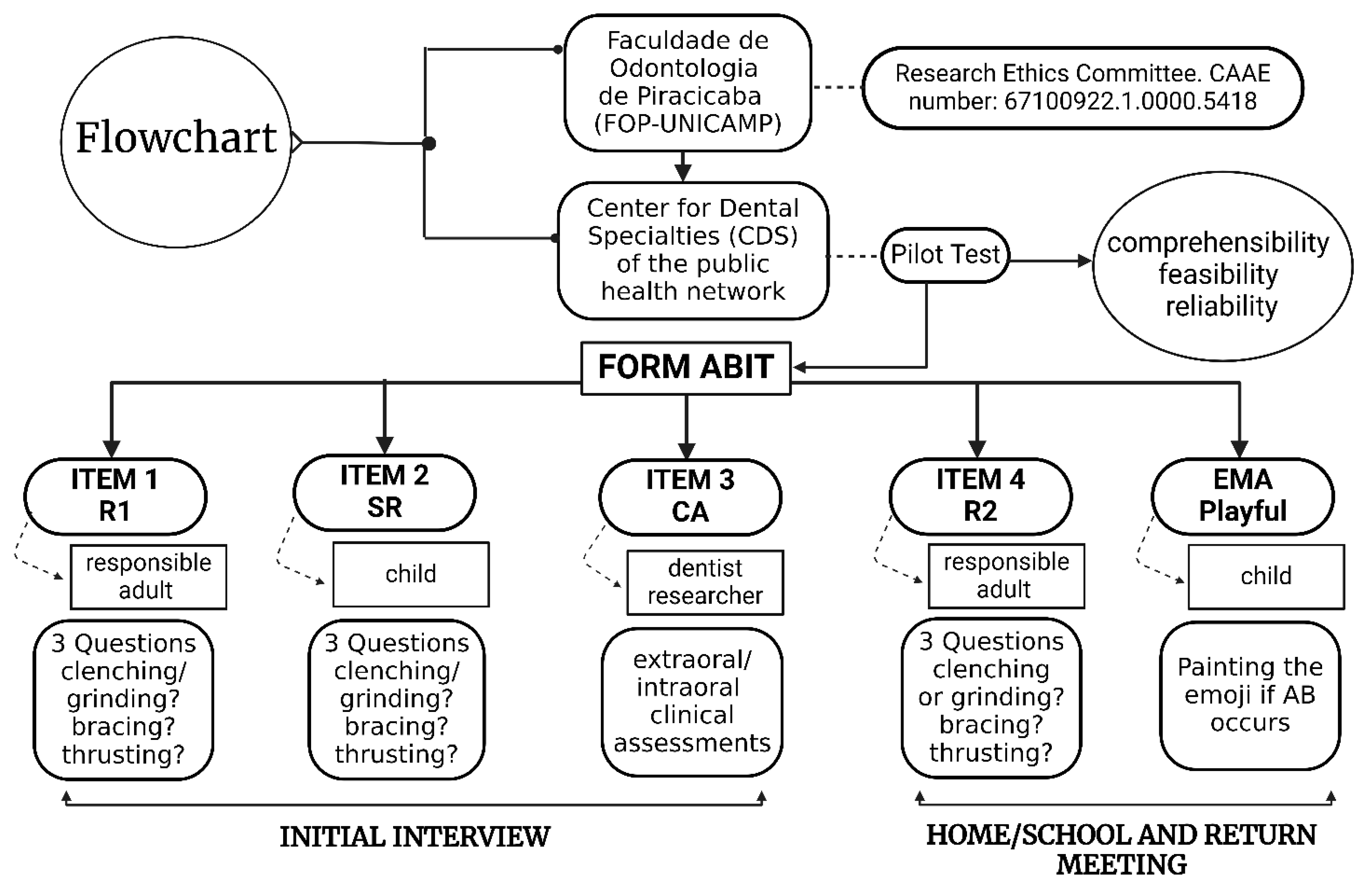

2. Materials and Methods

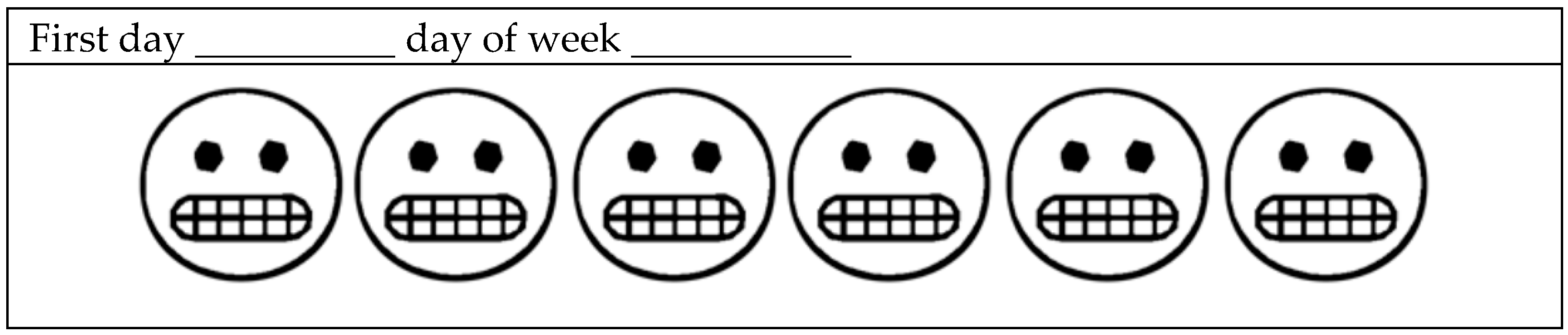

2.1. Tool Presentation

- During the ECA, the masseter and temporal muscles (right and left) are examined through visual inspection and palpation. The presence of hypertrophy is recorded as Yes (Y) or No (N). In the ECA, the same scoring criteria are applied, with 1 point assigned for the presence of masseter or temporalis muscle hypertrophy. The interpretation of masseter hypertrophy is determined based on three conditions that justify a “Yes” response: hypertrophy that is both palpable and visible during forced occlusion, visible hypertrophy with a prominent mandibular angle, and visible hypertrophy accompanied by exostosis at the mandibular angle. For the temporal muscle, the presence of hypertrophy is assessed based on whether it is palpable and visible both during forced occlusion and at rest.

- In the ICA, the jugal mucosa, tongue, and buccal mucosa are examined. All findings are to be recorded as Yes (Y) or No (N). In the ICA, 1 point is assigned for the presence of buccal hyperkeratosis (linea alba), labial hyperkeratosis, labial indentation, tongue indentation, and buccal indentation. Tooth wear is assessed and noted as complementary data and does not participate in the diagnosis. For this record, a “five-point ordinal scale” is used: Grade 0 = no visible wear; Grade 1 = visible enamel wear; Grade 2 = visible wear with dentin exposure and loss of clinical crown height ≤ 1/3; Grade 3 = loss of clinical crown height >1/3 but <2/3; and Grade 4 = loss of clinical crown height ≥ 2/3. Care is taken to distinguish wear from chemical erosion, following specific criteria [34,35].

2.2. Cut-Off Points and Data Interpretation

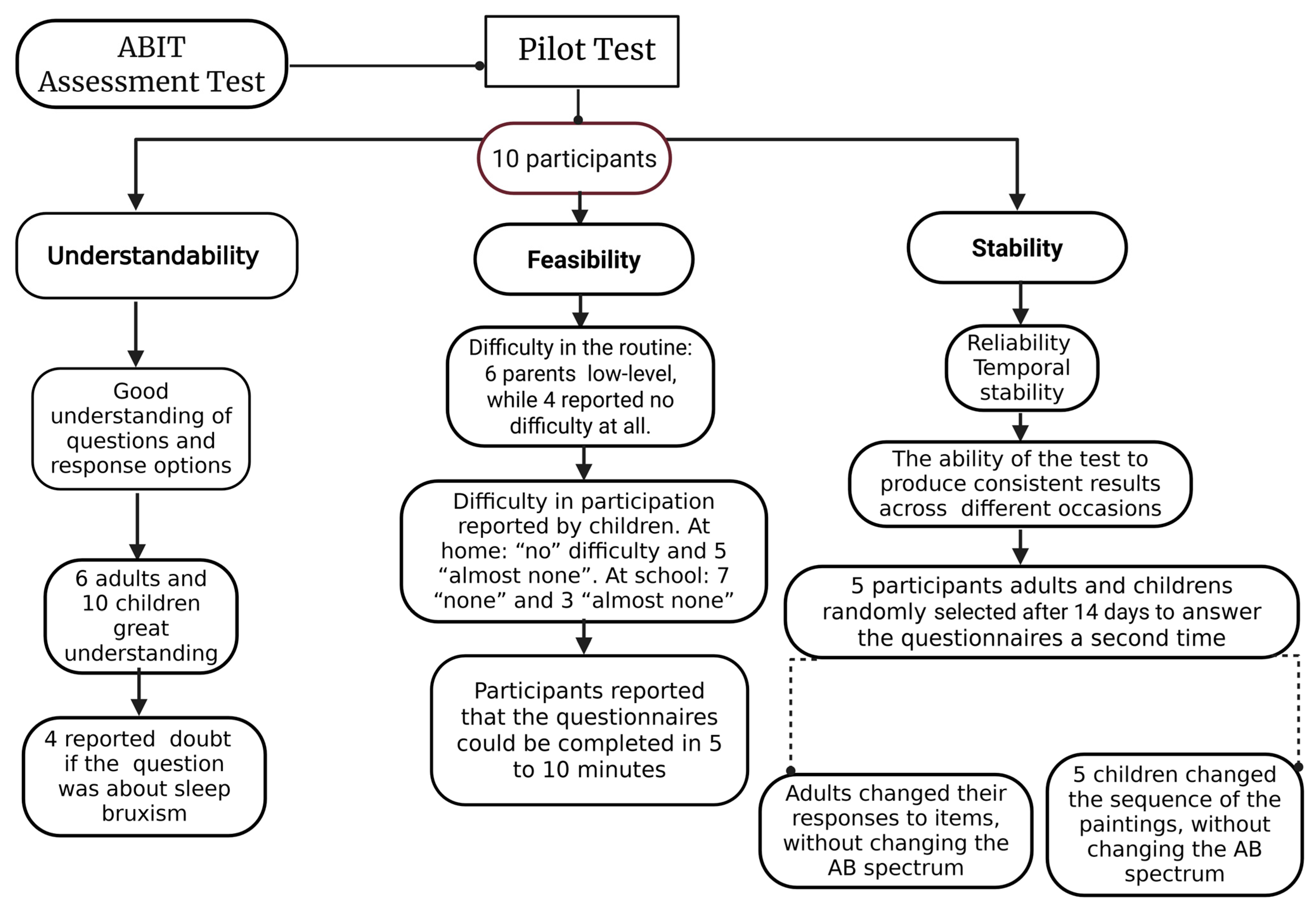

2.3. Pilot Study

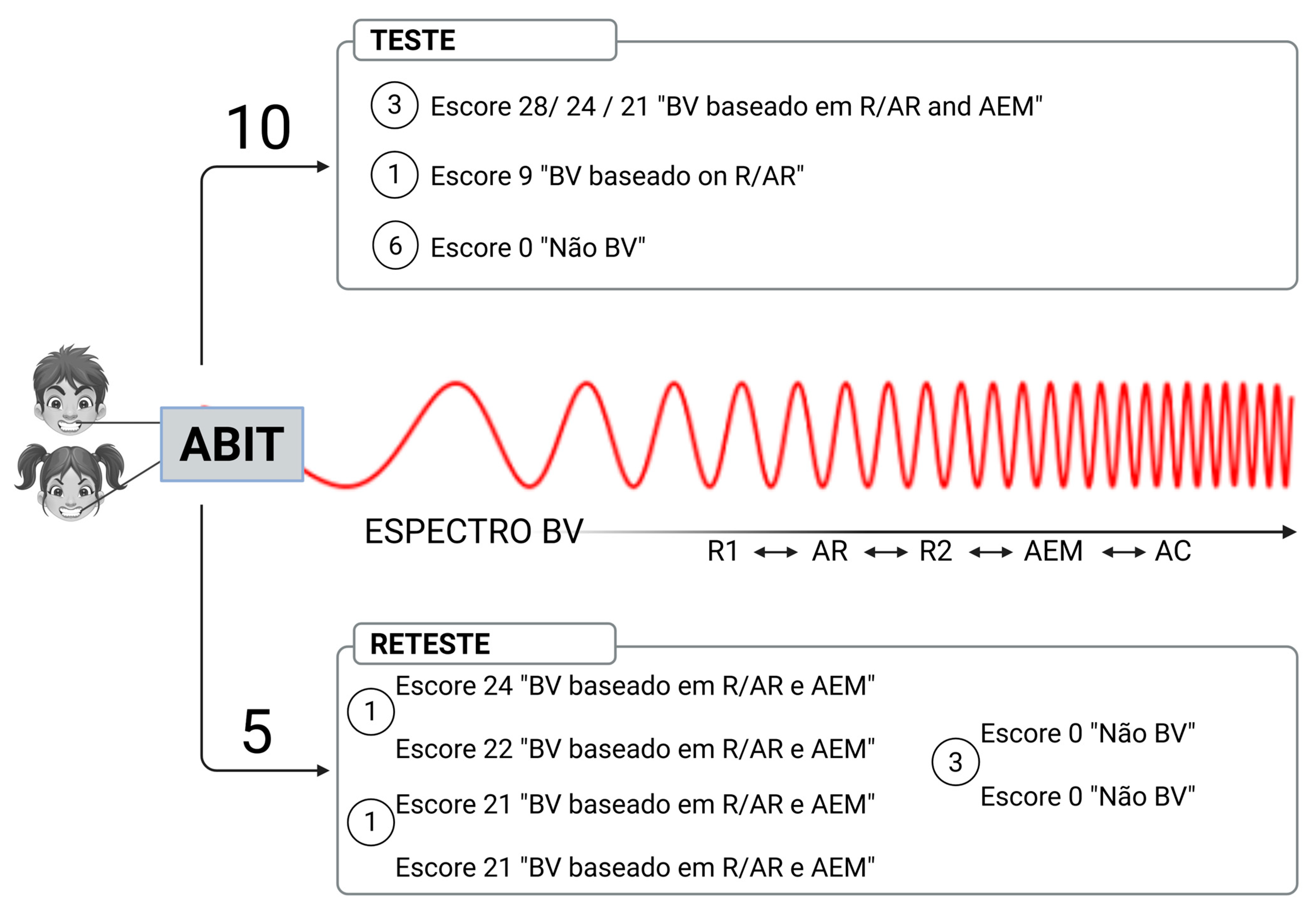

3. Results

3.1. Testing ABIT Items

3.2. AB Frequency in the Test Group

4. Discussion

4.1. About the Tool Development

4.2. The Pilot Test of the Tool

4.3. The Frequency of AB in the Pilot Group

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Test and Retest Results for ABIT Items

| Stage | Participant | Clinic Score | R1 Score | R2 Score | SR Score | EMA | ABIT Score | Spectrum AB | SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1 | 1 ** | 3 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 24 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | Yes |

| T | 2 | 0 | 0 | Null | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | Yes |

| T | 4 | 2 ** | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 21 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | No |

| T | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 7 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | <4 | 9 | AB based on R/SR | Yes |

| T | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| T | 9 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 28 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | DK |

| T | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | No |

| Test (T) versus Retest (R) | |||||||||

| T | 1 | 1 ** | 3 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 24 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | |

| R | 1 ** | 4 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 22 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | ||

| T | 4 | 2 ** | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 21 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | |

| R | 2 ** | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 21 | AB based on R/SR and EMA | ||

| T | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | ||

| T | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No AB | ||

| T | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | |

| R | 0 | 0 | 0 | Null | <4 | 0 | No AB | ||

Appendix A.2. Test and Retest Results for ABIT Items

| Stage | Participant | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1.85 |

| Test | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Test | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Test | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.14 |

| Test | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Test | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.28 |

| Test | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1.71 |

| Test | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.14 |

| Test (T) versus Retest (R) | |||||||||

| Test | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1.85 |

| Retest | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Test | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Retest | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Test | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.14 |

| Retest | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Retest | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Test | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.14 |

| Retest | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

Appendix B

| Participant | Degree 0 | Degree 1 | Degree 2 | Degree 3 | Degree 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 20 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

References

- Raphael, K.G.; Santiago, V.; Lobbezoo, F. Bruxism Is a Continuously Distributed Behaviour, but Disorder Decisions Are Dichotomous (Response to Letter by Manfredini, De Laat, Winocur, & Ahlberg (2016)). J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 802–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeff, M.C.; Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Bender, S.; Bracci, A.; Colonna, A.; Dal Fabbro, C.; Durham, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; et al. Updating the Bruxism Definitions: Report of an International Consensus Meeting. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Bracci, A.; Djukic, G. BruxApp: Uno Strumento per La Diagnosi Di Bruxismo Della Veglia Mediante Valutazione Ecologica Del Momento. Minerva Stomatol. 2016, 65, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Naeije, M. Bruxism Is Mainly Regulated Centrally, Not Peripherally. J. Oral Rehabil. 2001, 28, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Lobbezoo, F. Bruxism Definition: Past, Present, and Future—What Should a Prosthodontist Know? J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Pająk, A.; Wójcicki, M.; Litko-Rola, M.; Ginszt, M. Global Co-Occurrence of Bruxism and Temporomandibular Disorders: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torul, D.; Yılmaz, M.F.; Örnek Akdoğan, E.; Omezli, M.M. Temporomandibular Joint Disorders and Associated Factors in a Turkish Pediatric Population. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 4454–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Koyano, K.; Lavigne, G.J.; de Leeuw, R.; Manfredini, D.; Svensson, P.; Winocur, E. Bruxism Defined and Graded: An International Consensus. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; De Laat, A.; De Leeuw, R.; et al. International Consensus on the Assessment of Bruxism: Report of a Work in Progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Aarab, G.; Bracci, A.; Durham, J.; Ettlin, D.; Gallo, L.M.; Koutris, M.; Wetselaar, P.; Svensson, P.; et al. Towards a Standardized Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism (STAB)—Overview and General Remarks of a Multidimensional Bruxism Evaluation System. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Aarab, G.; Bracci, A.; Durham, J.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Ettlin, D.; Gallo, L.M.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Koutris, M.; et al. The Development of the Standardised Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism (STAB): An International Road Map. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Verhoeff, M.C.; Aarab, G.; Bracci, A.; Koutris, M.; Nykänen, L.; Thymi, M.; Wetselaar, P.; Manfredini, D. The Bruxism Screener (BruxScreen): Development, Pilot Testing and Face Validity. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracci, A.; Djukic, G.; Favero, L.; Salmaso, L.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Manfredini, D. Frequency of Awake Bruxism Behaviours in the Natural Environment. A 7-Day, Multiple-Point Observation of Real-Time Report in Healthy Young Adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, A.; Lombardo, L.; Siciliani, G.; Bracci, A.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Djukic, G.; Manfredini, D. Smartphone-Based Application for EMA Assessment of Awake Bruxism: Compliance Evaluation in a Sample of Healthy Young Adults. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nykänen, L.; Manfredini, D.; Lobbezoo, F.; Kämppi, A.; Colonna, A.; Zani, A.; Almeida, A.M.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Savolainen, A.; Bracci, A.; et al. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism with a Smartphone Application Requires Prior Patient Instruction for Enhanced Terminology Comprehension: A Multi-Center Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Bracci, A.; Colonna, A.; Ferrari, M.; Rodrigues Garcia, R.C.M.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism Frequency in Patients with Different Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.; Lima, R.; Prado, I.; Colonna, A.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Bracci, A.; Manfredini, D. Awake Bruxism Report in a Population of Dental Students with and without Ecological Momentary Assessment Monitorization–A Randomised Trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological Momentary Assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.M.; Alonso, L.S.; Vale, M.P.; Abreu, L.G.; Serra-Negra, J.M. Association between the Severity of Possible Sleep Bruxism and Possible Awake Bruxism and Attrition Tooth Wear Facets in Children and Adolescents. Cranio 2025, 43, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, S.O.; Ortiz, F.R.; Hoffmam, G.d.F.e.B.; Souza, G.L.N.; Prado, I.M.; Abreu, L.G.; Auad, S.M.; Serra-Negra, J.M. Probable Sleep and Awake Bruxism in Adolescents: A Path Analysis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 34, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, T.R.; de Lima, L.C.M.; Neves, É.T.B.; Arruda, M.J.A.L.L.A.; Perazzo, M.F.; Paiva, S.M.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Ferreira, F.d.M.; Granville-Garcia, A.F. Factors Associated with Awake Bruxism According to Perceptions of Parents/Guardians and Self-Reports of Children. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, I.M.; Abreu, L.G.; Pordeus, I.A.; Amin, M.; Paiva, S.M.; Serra-Negra, J.M. Diagnosis and Prevalence of Probable Awake and Sleep Bruxism in Adolescents: An Exploratory Analysis. Braz. Dent. J. 2023, 34, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto-Souza, D.; Mourão, P.S.; Barroso, H.H.; Douglas-de-Oliveira, D.W.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Falci, S.G.M.; Galvão, E.L. Is There an Association between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents and the Occurrence of Bruxism? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2020, 53, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk, A.; Wójcicki, M. Global Prevalence of Sleep Bruxism and Awake Bruxism in Pediatric and Adult Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman Rubin, P.; Erez, A.; Peretz, B.; Birenboim-Wilensky, R.; Winocur, E. Prevalence of Bruxism and Temporomandibular Disorders among Orphans in Southeast Uganda: A Gender and Age Comparison. Cranio 2018, 36, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetselaar, P.; Vermaire, E.J.H.; Lobbezoo, F.; Schuller, A.A. The Prevalence of Awake Bruxism and Sleep Bruxism in the Dutch Adolescent Population. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari-Piloni, C.; Barros, L.A.N.; Evangelista, K.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Silva, M.A.G.; Valladares-Neto, J. Prevalence of Bruxism in Brazilian Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, J.M.D.; Pauletto, P.; Massignan, C.; D’Souza, N.; Gonçalves, D.A.d.G.; Flores-Mir, C.; De Luca Canto, G. Prevalence of Awake Bruxism: A Systematic Review. J. Dent. 2023, 138, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi-Perlman, A.; Manfrendini, D.; Shalev, T.; Yevdayev, I.; Frideman-Rubin, P.; Bracci, A.; Arnias-Winocur, O.; Eli, I. Awake Bruxism—Single-Point Self-Report versus Ecological Momentary Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, R.; Manfredini, D.; Lenci, F.; Simeon, V.; Bracci, A.; Michelotti, A. Comparison between Ecological Momentary Assessment and Questionnaire for Assessing the Frequency of Waking-Time Non-Functional Oral Behaviours. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Colonna, A.; Bender, S.; Conti, P.C.R.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Klasser, G.D.; Michelotti, A.; Lavigne, G.J.; et al. Research Routes on Awake Bruxism Metrics: Implications of the Updated Bruxism Definition and Evaluation Strategies. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D. The Advancement of a Discipline: The Past, Present and Future of Bruxism Research. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter, N.; Amaechi, B.T.; Bartlett, D.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Carvalho, T.S.; Ganss, C.; Hara, A.T.; Huysmans, M.C.D.N.J.M.; Lussi, A.; Moazzez, R.; et al. Terminology of Erosive Tooth Wear: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by the ORCA and the Cariology Research Group of the IADR. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, C.; Ozgunaltay, G. Evaluation of Tooth Wear and Associated Risk Factors: A Matched Case-Control Study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillon, E.E.; Ou, K.L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Svensson, P. Sleep Bruxism: An Updated Review of an Old Problem. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2016, 74, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Health for the World’s Adolescents a Second Chance in the Second Decade; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- L8069. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8069.htm (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Saracutu, O.I.; Manfredini, D.; Bracci, A.; Val, M.; Ferrari, M.; Colonna, A. Comparison Between Ecological Momentary Assessment and Self-Report of Awake Bruxism Behaviours in a Group of Healthy Young Adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.L.; Fagundes, D.M.; Ferreira Soares, P.B.; Ferreira, M.C. Knowledge of Parents/Caregivers about Bruxism in Children Treated at the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic. Sleep Sci. 2019, 12, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, M.; Schmidt, S.; Muehlan, H.; Ulbricht, S.; Heckmann, M.; Berg, N.V.D.; Grabe, H.J.; Tomczyk, S. Ecological momentary assessment of parent-child attachment via technological devices: A systematic methodological review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2023, 73, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, L.; Manfredini, D.; Lobbezoo, F.; Kämppi, A.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J. Assessment of awake bruxism by a novel bruxism screener and ecological momentary assessment among patients with masticatory muscle myalgia and healthy controls. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Wetselaar, P.; Svensson, P.; Lobbezoo, F. The bruxism construct: From cut-off points to a continuum spectrum. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Ferrari, M.; Val, M.; Manfredini, D. Long-Term Study on the Fluctuation of Self-Reported Awake Bruxism in a Cohort of Healthy Young Adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiewicz, M.A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Pytko-Polończyk, J.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Principles for the Study of Awake Bruxism Behaviors, Part 2: Development of a Smartphone Application for a Multicenter Investigation and Chronological Translation for the Polish Version. Front. Neurol. 2019, 5, 110–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, K.; Fujisawa, M.; Saito-Murakami, K.; Miura, S.; Fujita, T.; Imamura, Y.; Koyama, S. Assessment of Awake Bruxism—Combinational Analysis of Ecological Momentary Assessment and Electromyography—. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2024, 68, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, J.D.; Steinke, E.G. Virtues, ecological momentary assessment/intervention and smartphone technology. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 6–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwasnicka, D.; ten Hoor, G.A.; Hekler, E.; Hagger, M.S.; Kok, G. Proposing a New Approach to Funding Behavioural Interventions Using Iterative Methods. Psychol. Health 2021, 36, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saballa de Carvalho, R.; Salazar Guizzo Arianna Lazzari, B.; Regina Brostolin, M.; Maria Filiu de Souza, T. A docência na educação infantil: Pontos e contrapontos de uma educação inclusiva teaching in early childhood education: Points and counterpoints of an inclusive education. Cad. Cedes 2023, 119, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluha, R.L.; Macário, H.S.; Câmara-Souza, M.B.; De la Torre Canales, G.; Ernberg, M.; Stuginski-Barbosa, J. Benefits of the Combination of Digital and Analogic Tools as a Strategy to Control Possible Awake Bruxism: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walentek, N.P.; Schäfer, R.; Bergmann, N.; Franken, M.; Ommerborn, M.A. Relationship between Sleep Bruxism Determined by Non-Instrumental and Instrumental Approaches and Psychometric Variables. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, G.J.; Rompré, P.H.; Montplaisir, J.Y. Sleep Bruxism: Validity of Clinical Research Diagnostic Criteria in a Controlled Polysomnographic Study. J. Dent. Res. 1996, 75, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenberg-Sydney, P.B.; Lorenzon, A.L.; Pimentel, G.; Petterle, R.R.; Bonotto, D. Probable Awake Bruxism—Prevalence and Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2022, 27, e2220298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, D.; Ganss, C.; Lussi, A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE): A New Scoring System for Scientific and Clinical Needs. Clin. Oral Investig. 2008, 12, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Bucci, R.; Conti, P.C.R.; Dias, R.; Emodi-Perlmam, A.; Favero, R.; Häggmän-Henrikson, B.; et al. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism Behaviors: A Scoping Review of Findings from Smartphone-Based Studies in Healthy Young Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 28, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.A.; Oliveira-Souza, A.I.S.; Hahn, G.; Bähr, L.; Armijo-Olivo, S.; Ferreira, A.P.L. Effectiveness of Biofeedback in Individuals with Awake Bruxism Compared to Other Types of Treatment: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Colonna, A.; Nykänen, L.; Pollis, M.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D.; International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology INfORM. Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives on Awake Bruxism Assessment: Expert Consensus Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Serra-Negra, J.; Carboncini, F.; Lobbezoo, F. Current Concepts of Bruxism. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Classical Test Theory. Med. Care 2006, 44, S50–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, L. Psicometria. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2009, 43, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, K.P.; De Cocker, K.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chow, C.; Laranjo, L. Smartphone-Delivered Ecological Momentary Interventions Based on Ecological Momentary Assessments to Promote Health Behaviors: Systematic Review and Adapted Checklist for Reporting Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Studies. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e22890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuert, C.E.; Kunz, T.; Gummer, T. An empirical evaluation of probing questions investigating question comprehensibility in web surveys. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2024, 28, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuert, C. The Effect of Question Positioning on Data Quality in Web Surveys. Sociol. Methods Res. 2024, 53, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, E.; Messer, T.; Eli, I.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Kedem, R.; Reiter, S.; Friedman-Rubin, P. Awake and Sleep Bruxism among Israeli Adolescents. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marceliano, C.R.V.; Gavião, M.B.D. Possible Sleep Bruxism and Biological Rhythm in School Children. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2979–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, A.C.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Guirardello, E.d.B. Propriedades psicométricas na avaliação de instrumentos: Avaliação da confiabilidade e da validade. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2017, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Kopin, I.J. Homeostatic Systems, Biocybernetics, and Autonomic Neuroscience. Auton. Neurosci. 2017, 208, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.S.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Abreu, L.G.; Martins, I.M.; Tourino, L.F.P.G.; Vale, M.P. Association between Possible Awake Bruxism and Bullying among 8- to 11-Year-Old Children/Adolescents. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani, A.; Lobbezoo, F.; Bracci, A.; Ahlberg, J.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Principles for the Study of Awake Bruxism Behaviors, Part 1: General Principles and Preliminary Data on Healthy Young Italian Adults. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Scores | Cut-off Values | Type of AB Identification | AB Spectrum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1 * | AB based on R/SR | 12 |

| SR | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1 * | AB based on R/SR | 12 |

| R2 | 0 a 4 | Greater than or equal to 1 * | AB based on R/SR | 12 |

| ICA | 0 a 6 | Greater than or equal to 1 ** | AB based on CA | 6 |

| ECA | 0 a 2 | Greater than or equal to 1 ** | AB based on CA | 2 |

| EMA | 0 a 42 | Greater than or equal to 4 days with paintings | AB based on R/SR and EMA | 42 |

| 96 |

| Cronbach’s α | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Agreement | ||

| R1 | 0.462 | 0.880 | 0.831 |

| R2 | 0.827 | ||

| Stage | AB Behavior | Reports R1 Parents | Reports R2 Parents | SR Children | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Teeth Griding | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Retest | Teeth Griding | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Test | Teeth Clenching | 1 | 5 | 5 | 11 |

| Retest | Teeth Clenching | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Test | Mandible Bracing/Thrusting | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| Retest | Mandible Bracing/Thrusting | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro-Araújo, N.R.; da Silva, A.C.F.; Marceliano, C.R.V.; Gavião, M.B.D. Awake Bruxism Identification: A Specialized Assessment Tool for Children and Adolescents—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070982

Ribeiro-Araújo NR, da Silva ACF, Marceliano CRV, Gavião MBD. Awake Bruxism Identification: A Specialized Assessment Tool for Children and Adolescents—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070982

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro-Araújo, Núbia Rafaela, Anna Cecília Farias da Silva, Camila Rita Vicente Marceliano, and Maria Beatriz Duarte Gavião. 2025. "Awake Bruxism Identification: A Specialized Assessment Tool for Children and Adolescents—A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070982

APA StyleRibeiro-Araújo, N. R., da Silva, A. C. F., Marceliano, C. R. V., & Gavião, M. B. D. (2025). Awake Bruxism Identification: A Specialized Assessment Tool for Children and Adolescents—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070982