This cross-sectional survey revealed significant differences in the patient or caregiver patterns of health information management and attitudes toward PGHD usage in terms of health-related roles, type of disease, and age group.

4.1. Principal Results

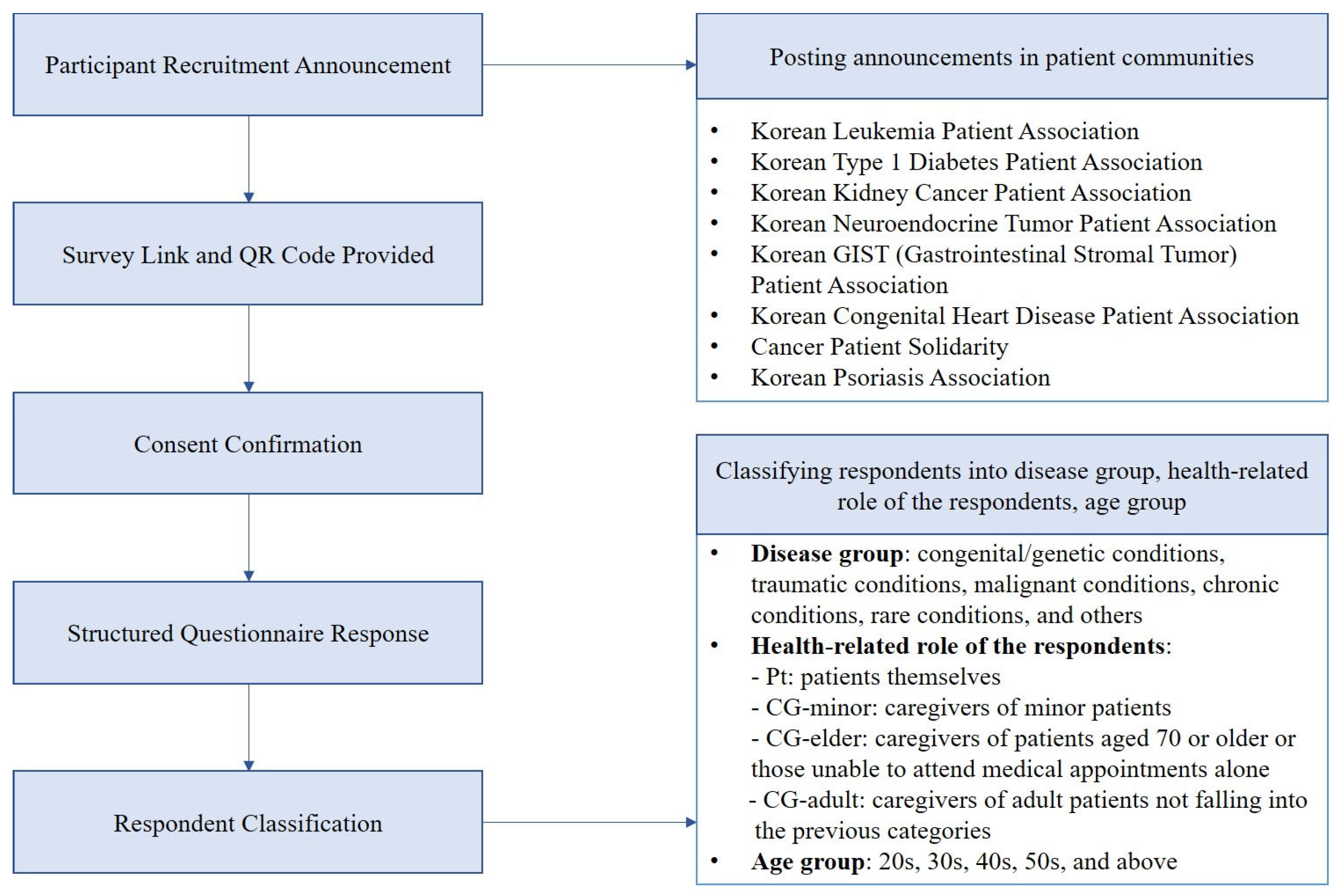

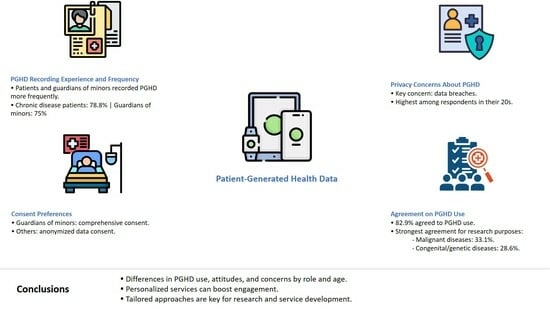

Differences were observed among respondent groups based on health-related roles (patients vs. guardians of minor patients), age, and sex distribution. These groups also varied in their experience and frequency of PGHD recording. Patients and guardians of minors (Pt and CG-minor) showed higher rates of PGHD recording and daily use compared to guardians of elderly or other adult patients. Overall, PGHD use was supported by a majority of respondents (average agreement rate of 82.9%), with concerns about personal information leakage being the most common reason for disagreement.

Despite these findings, the health-role-specific characteristics of PGHD use remain unclear. In a previous study, older users (mean age 51.81 vs. 43.81 years) were more likely to use PGHD functions continuously [

23]; however, the study did not distinguish between older adults using the services themselves and guardians recording data on their behalf.

In this study, PGHD recording experience significantly differed by age and disease (** p < 0.01). The highest usage rate was found among patients with chronic diseases (78.8%, 134/170), followed by guardians of minors (75.0%, 69/92). These patterns suggest a greater need for ongoing health monitoring and active involvement in care among these groups. Therefore, beyond clinical needs, health-related roles may also influence the active use of PGHD.

The significance of this study lies in its distinction between PGHD users who were patients and those who were guardians, enabling a more nuanced analysis. Notable differences emerged in the use of patient apps provided by healthcare institutions, with the CG-minor group showing a higher willingness to use these apps. This group was also more likely to consent to the use of identifiable data for comprehensive, loss-free data utilization, whereas guardians in other groups preferred the use of anonymized data.

Survey results showed that among respondents who answered “strongly agree” to PGHD use, more supported its use for research (N = 100) than for clinical purposes (N = 95). Despite being a secondary use, PGHD for research was actively supported, particularly in the context of cancer and rare diseases. Respondents with malignant conditions showed the highest rate of strong agreement for research use (33.1%, 40/121). In the congenital/genetic disease group, support for research use (28.6%, 14/49) exceeded that for clinical use (18.4%, 9/49) by 10.2%. Support for PGHD in research was especially strong among those with malignant diseases, suggesting a greater interest in advancing scientific knowledge or perceived benefits from research-informed care.

This study identified age-related disparities in PGHD use. Compared to respondents in their 40s and 50s, younger individuals (20s and 30s) reported lower rates of PGHD recording. Reasons for discontinuing health management app use varied by age: younger respondents cited annoyance, while older users pointed to usability difficulties. Younger participants also showed lower intention to use such services and were less supportive of PGHD use for research purposes. Among those in their 20s, data protection and security were the most sought-after information when consenting to PGHD use.

These findings align with prior research indicating stronger concerns among younger users regarding mobile health (mHealth) services [

24], consistent with the broader understanding that demographic characteristics influence behavioral intentions [

25]. However, age-specific patterns in PGHD use remain underexplored. Collectively, this and previous studies highlight differences in attitudes and experiences with health data recording and management across age groups, underscoring the need to tailor engagement strategies to each demographic to promote inclusive participation in healthcare.

The most common reason for selecting specific (individual) consent for secondary PGHD use was a desire for clearer understanding of the process. The top responses—“want to know specific research purposes, contents, duration” and “want to know how personal information is used in research”—emphasize the importance of transparency and communication. In contrast, “convenience” was the primary reason for selecting comprehensive consent, suggesting that both informed understanding and procedural simplicity are key factors in user engagement. These findings are critical for designing systems that effectively obtain consent for the secondary use of PGHD.

In South Korea, while the Medical Service Act does not explicitly grant a right to data portability, patients can access their medical records, thereby enabling data portability with their consent. Recent amendments to the Personal Information Protection Act—specifically Article 35-2, enacted on 14 March 2023—formally grant individuals the right to request data transmission, aligning with the patient-centric data rights framework of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This amendment represents a significant step toward enhancing patient autonomy and underscores the need for further revisions to the Medical Service Act to more effectively support data portability in practice. Moreover, the finding that patients and their caregivers differ in their perceptions of PGHD use and their willingness to consent to secondary use has important implications for policymakers.

Despite Korea’s advanced medical information infrastructure and highly trained workforce, current legal provisions remain insufficient to ensure that requests for medical information transmission are patient-centered. In contrast, the United States enforces interoperability and information blocking rules under the HITECH Act, with HIPAA safeguarding medical transmission requests—though its data-sharing efforts are primarily coordinated at the regional rather than national level. To facilitate practical and differentiated policy decisions to leverage PGHD that can be linked to clinical practice, it is necessary to understand that patient and caregiver populations also have heterogeneity.

4.2. Limitations

The biggest limitation of the present study is that it was an online survey that targeted individuals belonging to the patient community. This population may not represent the general patient and caregiver population owing to potential bias in interest or engagement. Online surveys are limited; however, participants are more likely to have easy access to the internet. Furthermore, individuals belonging to the patient community are likely to have more active tendencies than patients or guardians who do not [

26]. The 2016 National Statistics of Korea revealed that the median outpatient age was 50–54 years old, with approximately one-third (31.6%) of the participants being aged ≥65 years [

27]. The age group with the most respondents in the present survey was the 40s (N = 170), with those aged ≥50 years accounting for 14.5% (58/400) of the total respondents. This is lower than the age distribution estimated in 2016. The inability of pediatric/older patients to directly respond was another limitation. Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the respondents were likely to have high accessibility to online information and make decisions regarding the use of PGHD. Hence, although bias in the selection of respondents was inevitable, the results of the present study better reflect the real world. Moreover, the female participants were proportionally overrepresented in the CG-minor group; this gender disparity potentially limits the broader applicability of our findings concerning gender-specific perspectives. Consequently, our results might not comprehensively reflect the subtle distinctions in attitudes toward caregiving responsibilities and PGHD interaction. Further investigative studies are recommended to examine gender-based variations in these areas using more balanced participant sampling.

The present study was based on the findings of a survey conducted only in Korea; thus, the results may not be generalizable. However, Korea exhibits a high level of development and maturity in terms of the use of EMR. Furthermore, citizens have high accessibility to online information. Thus, the use of this cohort facilitated a meaningful start to this discussion [

28,

29]. A national project for patient-centered health data utilization is being promoted in Korea. Consequently, confirming the awareness regarding the utilization of PGHD and its implementation in the establishment of systems and processes is necessary [

30]. The present study confirmed patient awareness of PGHD usage and utilization; however, it was limited by its cross-sectional design. Awareness can change as the health status worsens or improves, and the health-related roles are also dynamic over time. These findings indicate the limitation of the questionnaire in its ability to address patient expectations and concerns. Technological advancements and policy changes can also affect patient awareness or attitudes towards PGHD. Thus, a continuous, multidisciplinary approach must be developed, and further research must be conducted in the future.

As with most survey-based studies, responses may have been affected by recall or acquiescence bias, particularly in Likert-scale items. Additionally, the inherent limitations of survey methods hindered the collection of in-depth participant insights, warranting further research.