Characterization of Tiered Psychological Distress Phenotypes in an Orthopaedic Sports Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Cohort Selection

2.2. Patient and Survey Data

2.3. Latent Class Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Transparency and Openness

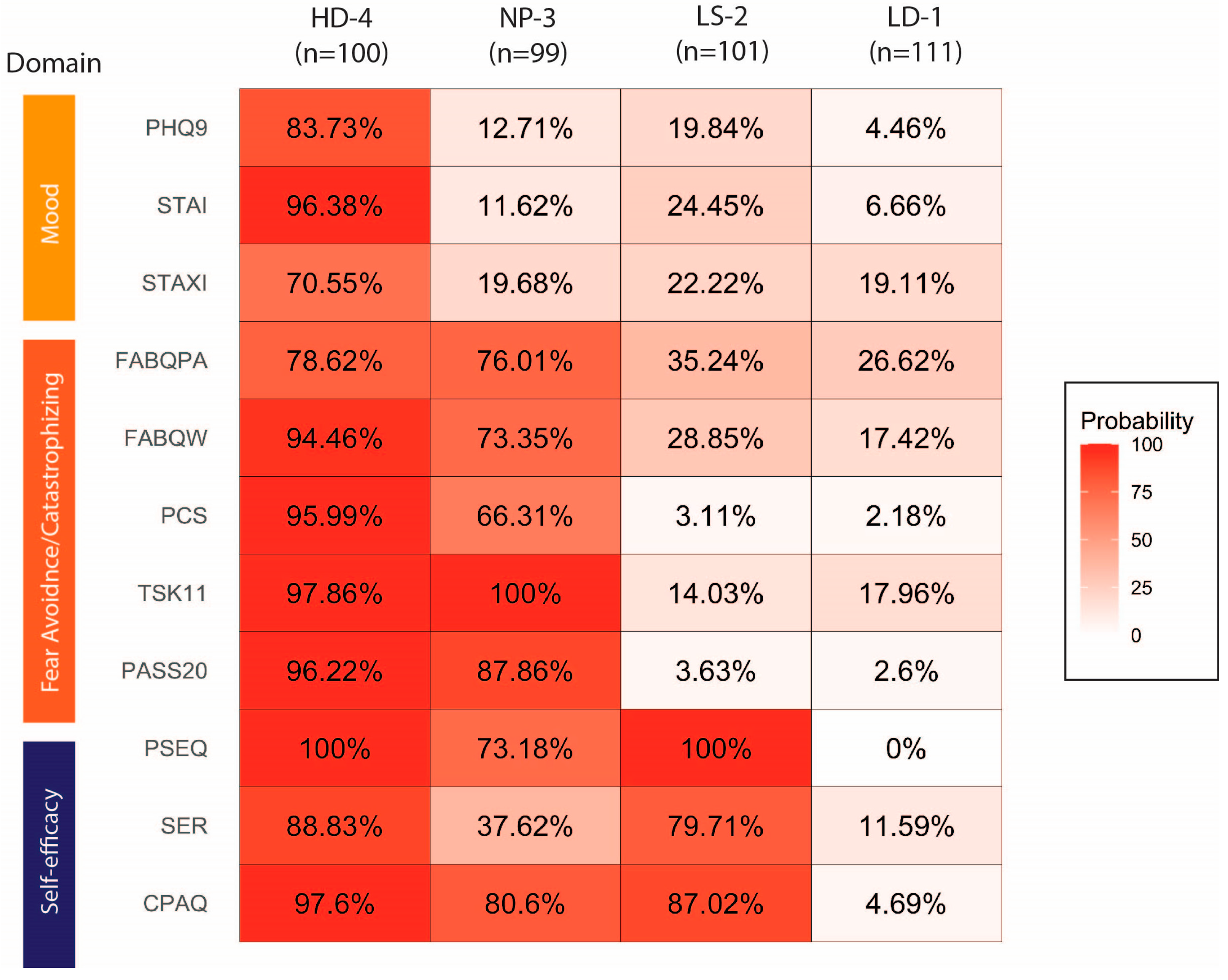

3. Results

4. Discussion

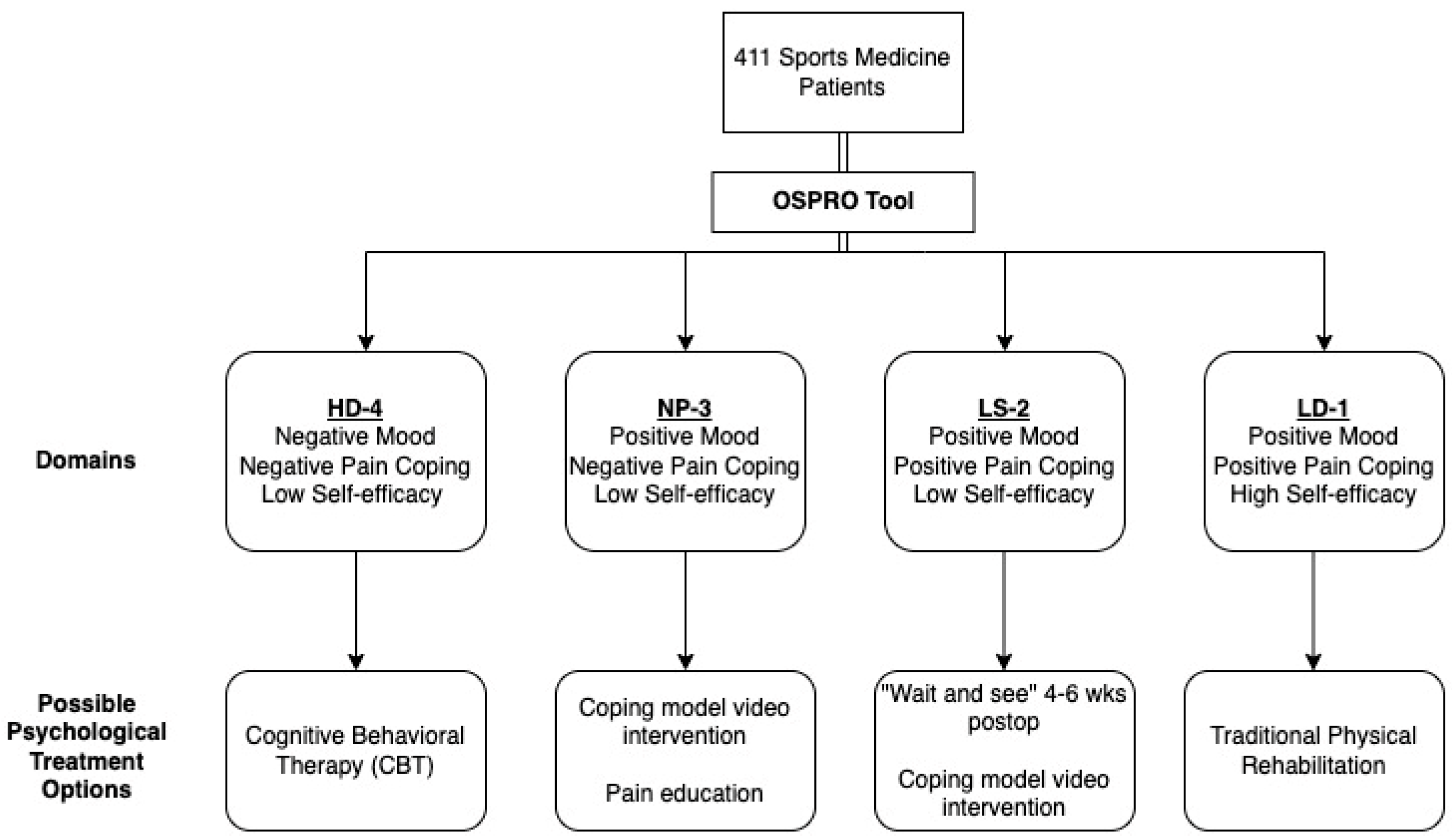

- (1)

- Patients in HD-4 may be most likely to benefit from early psychosocial interventions and more frequent monitoring. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is highly effective in reducing psychological distress following surgery and improves long-term scores for quality of life and reduced anxiety [27], but it is time-intensive and can be expensive for the patient. Because psychological interventions can be resource-intensive, it is important to limit referrals for CBT to patients that are most likely to benefit from it, such as patients with a HD-4 phenotype.

- (2)

- Patients in NP-3 (poor pain coping and low self-efficacy) may benefit from lower-intensity interventions to enhance coping and self-efficacy, such as coping model video interventions, where models perform rehabilitation exercises, reflect on problems faced, and discuss strategies to overcome them in one preoperative and one postoperative video (total duration of 16 min) [28]. Coping model interventions are aimed at reducing anxiety and perceptions of pain, which is thought to improve self-efficacy and function in the postoperative rehabilitation period [29,30,31]. Studies have also demonstrated the efficacy of combining education led by a physical therapist with impairment-based interventions in lowering both pain catastrophizing scores and coping skill strategies [32,33,34,35]. Specifically, one-on-one pain neuroscience education (helping patients to re-conceptualize their pain from a neurobiological perspective) with information booklets is another option for lower-intensity intervention.

- (3)

- Patients in LS-2 may be most likely to naturally transition to a low-distress phenotype over the course of routine rehabilitation as their confidence in physical activity improves. For this reason, these patients may benefit most from a “wait and see” approach, where traditional rehabilitation is offered and psychological distress is monitored over the first 4–6 weeks of rehabilitation to determine whether psychologically focused interventions are warranted.

- (4)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSPRO-YF | Optimal Screening or Prediction of Referral and Outcome—Yellow Flag |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| ASES | American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Score |

| IKDC | International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| STAXI | State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory |

| FABQ | Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire |

| TSK-11 | Tampa Scale of Kinesaphobia-11 |

| PCS | Pain Catastrophizing Scale |

| SER | Self-Efficacy for Rehabilitation Outcome Scale |

| CPAQ | Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SANE | Single Assessment Numerical Evaluation |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| HD-4 | High Distress Class 4 |

| LD-1 | Low Distress Class |

| LS-2 | Low Self-Efficacy Class 2 |

| NP-3 | Negative Pain Coping Class 3 |

References

- Samitier, G.; Marcano, A.I.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Cugat, R.; Farmer, K.W.; Moser, M.W. Failure of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2015, 3, 220–240. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki, K.; Sugaya, H. Complications after arthroscopic labral repair for shoulder instability. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2015, 8, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poleshuck, E.L.; Bair, M.J.; Kroenke, K.; Damush, T.M.; Tu, W.; Wu, J.; Krebs, E.E.; Giles, D.E. Psychosocial stress and anxiety in musculoskeletal pain patients with and without depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piussi, R.; Krupic, F.; Senorski, C.; Svantesson, E.; Sundemo, D.; Johnson, U.; Senorski, E.H. Psychological impairments after ACL injury—Do we know what we are addressing? Experiences from sports physical therapists. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, G.S.; Sell, T.C.; Zarega, R.; Reiter, C.; King, V.; Wrona, H.; Mills, N.; Ganderton, C.; Duhig, S.; Raisasen, A.; et al. Kinesiophobia, Knee Self-Efficacy, and Fear Avoidance Beliefs in People with ACL Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 3001–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, J.S.; Pimentel, S.D.; Yakobov, E.; Edwards, R.R. A Systematic Review of the Association Between Perceived Injustice and Pain-Related Outcomes in Individuals with Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 1449–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Ademi, Z.; Osborne, R.H.; Liew, D. Comparison of Health-Related quality of life, work status, and health care utilization and costs according to hip and knee joint disease severity: A national Australian study. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbay, S.R.; Ackerman, I.N.; Russell, T.G.; Macri, E.M.; Crossley, K.M. Health-Related quality of life after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Fotis, K.; Pearson, L.; Schoch, P.; Broughton, N.; Brennan-Olsen, S.L.; Bucknill, A.; Cross, E.; Bunting-Frame, N.; Page, R.S. Impaired Health-Related quality of life, psychological distress, and productivity loss in younger people with persistent shoulder pain: A cross-sectional analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 3785–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, S.R.; Fitzgerald, G.K.; Wisniewski, S.; Delitto, A. Predictors of pain and function outcome after rehabilitation in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, H.; Turk, D.C. Chronic back pain and rheumatoid arthritis: Predicting pain and disability from cognitive variables. J. Behav. Med. 1988, 11, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, J.P.; Jildeh, T.R.; Buckley, P.J.; Abbas, M.J.; Mumuni, S.; Okoroha, K.R. Older, Heavier, Arthritic, Psychiatrically Disordered, and Opioid-Familiar Patients Are at Risk for Opioid Use After Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2021, 3, e2025–e2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.M.; Baker, R.; Goltz, D.E.; Wickman, J.; Lentz, T.A.; Cook, C.; George, S.Z.; Klifto, C.S.; Anakwenze, O.A. Heterogeneity of Pain-Related psychological distress in patients seeking care for shoulder pathology. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2022, 31, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, H.; Rijk, L.; Thomas, J.; Ring, D.; Reichel, L.M.; Fatehi, A. Mental-Health Phenotypes and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Upper-Extremity Illness. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2021, 103, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.M.; Daltro, C.; Kraychete, D.C.; Lopes, J. The cognitive behavioral therapy causes an improvement in quality of life in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2012, 70, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olason, M.; Andrason, R.H.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Kristbergsdottir, H.; Jensen, M.P. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in an Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation Program for Chronic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial with a 3-Year Follow-up. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 25, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, T.A.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Bialosky, J.E.; Zeppieri, G., Jr.; Dai, Y.; Wu, S.S.; George, S.Z. Development of a Yellow Flag Assessment Tool for Orthopaedic Physical Therapists: Results From the Optimal Screening for Prediction of Referral and Outcome (OSPRO) Cohort. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, P.; Calfee, C.S.; Delucchi, K.L. Practitioner’s Guide to Latent Class Analysis: Methodological Considerations and Common Pitfalls. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e63–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, T.A.; George, S.Z.; Manickas-Hill, O.; Malay, M.R.; O’Donnell, J.; Jayakumar, P.; Jiranek, W.; Mather, R.C., 3rd. What General and Pain-Associated Psychological Distress Phenotypes Exist Among Patients with Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020, 478, 2768–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J.K.; Magidson, J. Latent Gold 4.0 User’s Guide; Statistical Innovations Inc.: Belmont, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, T.; Schmukler, J.; Castrejon, I. Patient questionnaires in osteoarthritis: What patients teach doctors about their osteoarthritis on a multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) in clinical trials and clinical care. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. 120), 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.C.; Dunn, K.M.; Main, C.J.; Hay, E.M. Subgrouping low back pain: A comparison of the STarT Back Tool with the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J.; Hallden, K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin. J. Pain 1998, 14, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelson, A.J.; George, S.Z.; Maluf, K.S.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E. Future directions in painful knee osteoarthritis: Harnessing complexity in a heterogeneous population. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundell, S.D.; Goode, A.P.; Suri, P.; Heagerty, P.J.; Comstock, B.A.; Friedly, J.L.; Gold, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Avins, A.L.; Nedeljkovic, S.S.; et al. Effect of Comorbid Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis on Longitudinal Clinical and Health Care Use Outcomes in Older Adults With New Visits for Back Pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeverenyi, C.; Kekecs, Z.; Johnson, A.; Elkins, G.; Csernatony, Z.; Varga, K. The Use of Adjunct Psychosocial Interventions Can Decrease Postoperative Pain and Improve the Quality of Clinical Care in Orthopedic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Pain 2018, 19, 1231–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, R.; Prapavessis, H.; Clatworthy, M. Modeling and rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Ann. Behav. Med. 2006, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, F.A. The Psychological Effects of Modeling in Athletic Injury Rehabilitation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, F. Integrating sport psychology and sports medicine in research. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1997, 10, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, M.S.; Sell, K.E.; Shelbourne, K.D.; Klootwyk, T.E. Current concepts on accelerated ACL rehabilitation. J. Sport Rehabil. 1994, 3, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Puentedura, E.J.; Diener, I.; Peoples, R.R. Preoperative therapeutic neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: A single-case fMRI report. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2015, 31, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Rico, D.; Langerwerf, L.; Maiers, N.; Diener, I.; Cox, T. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for shoulder surgery: A case series. S. Afr. J. Physiother. 2020, 76, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluch, E.; Duenas, L.; Falla, D.; Baert, I.; Meeus, M.; Sanchez-Frutos, J.; Nijs, J. Preoperative Pain Neuroscience Education Combined With Knee Joint Mobilization for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, E.; Sabo, M.T. Can pain catastrophizing be changed in surgical patients? A scoping review. Can. J. Surg. 2018, 61, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, Z.R.; Carvalho, M.L.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Lentz, T.A. Screening for Yellow Flags in Orthopaedic Physical Therapy: A Clinical Framework. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model—Number of Classes (k) | df | BIC | AIC | Likelihood Ratio | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 400 | 6062.53 | 6073.53 | 2454.8055 | - |

| 2 | 388 | 4887.78 | 4910.78 | 1207.8278 | 0.931 |

| 3 | 376 | 4646.53 | 4681.53 | 894.3603 | 0.956 |

| 4 * | 364 | 4509.19 | 4556.19 | 684.7953 | 0.929 |

| 5 | 352 | 4463.11 | 4522.11 | 566.4881 | 0.952 |

| 6 | 340 | 4444.32 | 4515.32 | 475.476 | 0.911 |

| Model—Number of Classes (k) | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | Class 5 | Class 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 43.80% | 56.20% | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | 42.09% | 28.22% | 29.68% | - | - | - |

| 4 * | 24.33% | 24.09% | 24.57% | 27.01% | - | - |

| 5 | 18.20% | 9.25% | 22.87% | 24.33% | 25.30% | |

| 6 | 25.30% | 18.00% | 8.52% | 6.60% | 18.25% | 23.36% |

| HD-4 | NP-3 | LS-2 | LD-1 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 100 | 99 | 101 | 111 | |

| Age, mean (sd) | 39.84 (17.52) | 44.42 (18.32) | 39.49 (18.19) | 45.49 (17.90) | 0.028 |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Caucasian/White | 45 (45.0) | 62 (62.6) | 72 (71.3) | 90 (81.1) | |

| Black or African American | 43 (43.0) | 27 (27.3) | 18 (17.8) | 16 (14.4) | |

| Other/Mixed/Not Reported | 12 (12.0) | 10 (10.1) | 11 (10.9) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Ethnicity = Hispanic (%) | 31 (47.0) | 29 (50.0) | 39 (63.9) | 40 (56.3) | 0.235 |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 4 (4.2) | 7 (7.4) | 5 (5.2) | 5 (4.8) | 0.784 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (sd) | 31.30 (7.61) | 29.60 (7.37) | 28.43 (6.17) | 28.94 (6.35) | 0.084 |

| Current Smoker, n (%) | 10 (14.5) | 7 (10.3) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.7) | 0.032 |

| General Anesthesia (vs. Other), n (%) | 11 (16.4) | 8 (11.8) | 4 (5.9) | 7 (9.3) | 0.247 |

| Procedure, n (%) | - | - | - | - | 0.458 |

| - | - | - | - | - | Totals |

| AC Joint/Clavicle Resection | 12 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (4.5) |

| ACL, PCL, or Other Ligamentous Repair | 63 (15.3) | 16 (16.0) | 14 (14.1) | 18 (17.8) | 15 (13.5) |

| LUA/MUA | 2 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Meniscus/Chondroplasty | 145 (35.3) | 37 (37.0) | 37 (37.4) | 32 (31.7) | 39 (35.1) |

| MPFL Recon | 12 (2.9) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (1.8) |

| ORIF | 43 (10.5) | 12 (12.0) | 9 (9.1) | 11 (10.9) | 11 (9.9) |

| Other/Unspecified | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.8) |

| Rotator Cuff Repair | 60 (14.6) | 13 (13.0) | 20 (20.2) | 14 (13.9) | 13 (11.7) |

| Shoulder Labral/Capsule Repair | 33 (8.0) | 13 (13.0) | 5 (5.1) | 7 (6.9) | 8 (7.2) |

| Tenodesis/Tenotomy | 37 (9.0) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.1) | 10 (9.9) | 16 (14.4) |

| HD-4 | NP-3 | LS-2 | LD-1 | p-Value | Post Hoc Pairwise Differences * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 100 | 99 | 101 | 111 | ||

| Pain, mean (sd) | 4.61 (3.30) | 3.71 (2.95) | 2.03 (2.62) | 2.66 (2.50) | <0.001 * | 4-2; 4-1; 3-2 |

| SANE, mean (sd) | 36.97 (26.88) | 41.44 (26.14) | 43.61 (31.17) | 48.07 (26.19) | 0.153 | |

| ASES, mean (sd) | 35.52 (21.49) | 40.22 (26.03) | 60.42 (28.31) | 52.25 (15.57) | 0.029 * | none |

| ASES unaffected side, mean (sd) | 80.33 (27.17) | 88.70 (20.77) | 96.94 (4.76) | 88.50 (21.61) | 0.439 | |

| IKDC, mean (sd) | 30.76 (21.61) | 33.43 (15.36) | 37.06 (17.90) | 38.25 (14.58) | 0.334 | |

| IKDC unaffected side, mean (sd) | 77.80 (20.45) | 79.40 (24.76) | 84.33 (20.35) | 88.67 (16.89) | 0.188 | |

| PROMIS category, mean (sd) | ||||||

| Physical Function | 33.58 (8.66) | 35.02 (10.91) | 36.35 (9.44) | 38.19 (9.45) | 0.091 | |

| Pain Interference | 67.08 (7.11) | 63.49 (7.84) | 60.84 (8.52) | 61.46 (6.85) | <0.001 * | 4-2; 4-1 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 59.36 (11.25) | 53.90 (9.79) | 51.59 (6.67) | 52.18 (9.85) | 0.007 * | none |

| Depression | 57.05 (10.88) | 48.91 (9.64) | 45.61 (8.05) | 45.96 (8.20) | <0.001 * | 4-3; 4-2; 4-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.I.; Morriss, N.J.; Stauffer, T.P.; Ralph, J.E.; Park, C.N.; Lentz, T.A.; Lau, B.C. Characterization of Tiered Psychological Distress Phenotypes in an Orthopaedic Sports Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060914

Kim BI, Morriss NJ, Stauffer TP, Ralph JE, Park CN, Lentz TA, Lau BC. Characterization of Tiered Psychological Distress Phenotypes in an Orthopaedic Sports Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060914

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Billy I., Nicholas J. Morriss, Taylor P. Stauffer, Julia E. Ralph, Caroline N. Park, Trevor A. Lentz, and Brian C. Lau. 2025. "Characterization of Tiered Psychological Distress Phenotypes in an Orthopaedic Sports Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060914

APA StyleKim, B. I., Morriss, N. J., Stauffer, T. P., Ralph, J. E., Park, C. N., Lentz, T. A., & Lau, B. C. (2025). Characterization of Tiered Psychological Distress Phenotypes in an Orthopaedic Sports Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060914