Protecting Repositories of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Health-Focused Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Review Objectives

1.2. Positionality

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Design

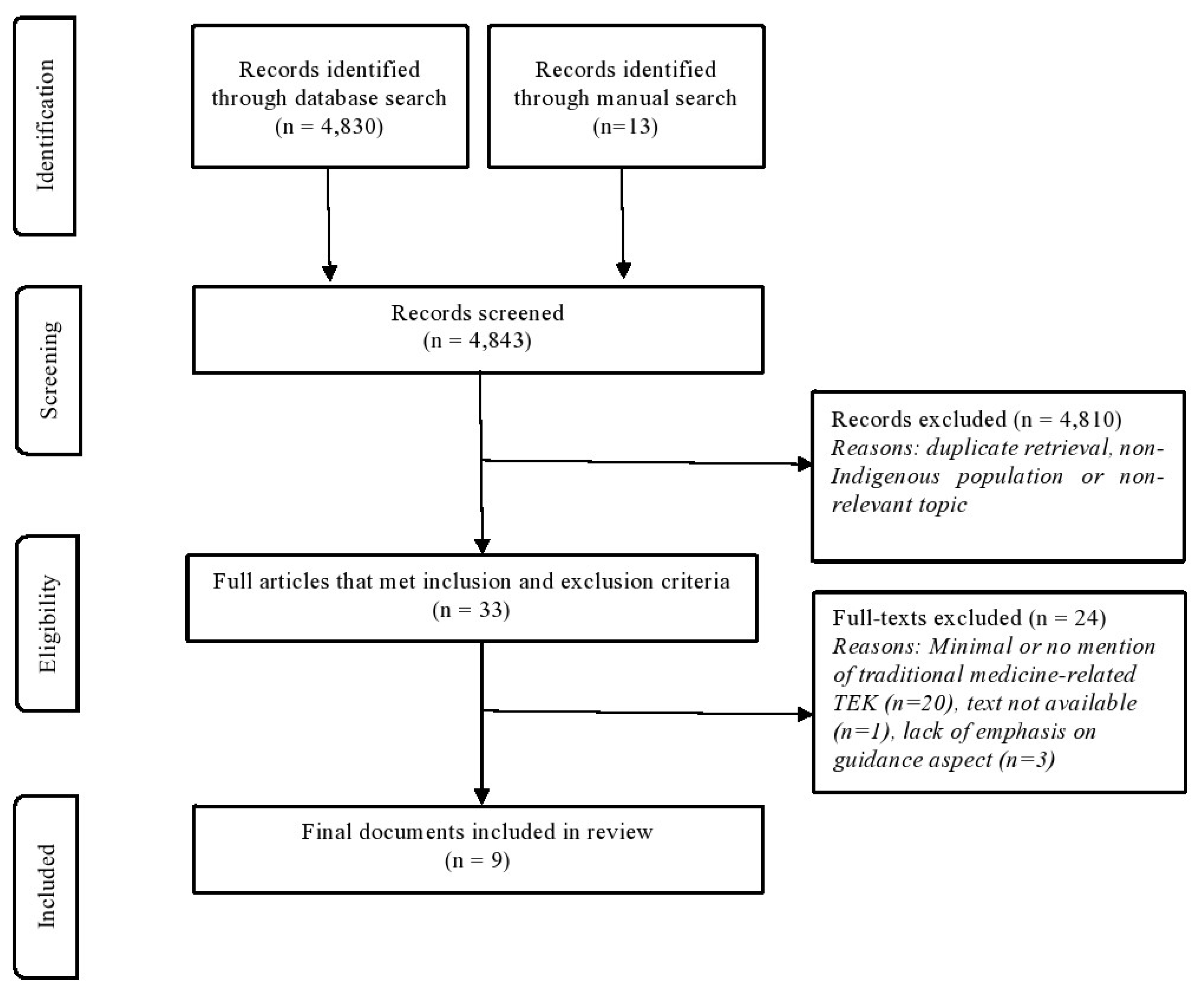

2.2. Search Terms, Procedures, and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Article Screening

2.4. Data Characterization, Summary, and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Impacts on Indigenous Health and Wellbeing-Related TEK Repositories

[m]ost archives and libraries hold information of a confidential, sensitive, or sacred nature… For Native American communities, the public release of or access to specialized information or knowledge—gathered with and without informed consent—can cause irreparable harm [38].

3.2. Indigenous Traditional Knowledge Are Diverse, Living Health-Embodying Knowledges

3.3. Indigenous Data Concerns Around Ethics, Ownership, Use, and Governance in the Management of TEK Archives

3.4. Platforming Indigenous Peoples’ Access and Rights to Their Data in Repositories

3.5. Securing and Protecting Indigenous Data in an Honorable Way Is Important

3.6. Wise Practices and Challenges in Supporting Indigenous-Led Repository Development

4. Discussion

[Indigenous] communities are encountering more frequent destructive storms, fire, and flooding, putting them and their [T]ribal histories and land stewardship at great risk. It is imperative to create accessible, digital versions of valuable and threatened knowledges [43].

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Redvers, N. The Value of Global Indigenous Knowledge in Planetary Health. Challenges 2018, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Celidwen, Y.; Schultz, C.; Horn, O.; Githaiga, C.; Vera, M.; Perdrisat, M.; Mad Plume, L.; Kobei, D.; Cunningham Kain, M.; et al. The determinants of planetary health: An Indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e156–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, D. Indigenous knowledge systems in environmental governance in Canada. KULA 2021, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Aubrey, P.; Celidwen, Y.; Hill, K. Indigenous Peoples: Traditional knowledges, climate change, and health. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildcat, D. Traditional Ecological Knowledges. In Re-Indigenizing Ecological Consciousness and the Interconnectedness to Indigenous Identities; Montgomery, M., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2022; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, G. Native Science and Sustaining Indigenous Communities. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability; New Directions in Sustainability and Society; Nelson, M.K., Shilling, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic & Social Council (UNESC). Indigenous determinants of health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), New York, NY, USA, 17–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic & Social Council (UNESC). Improving the health and wellness of Indigenous Peoples globally: Operationalization of Indigenous determinants of health. In Proceedings of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), New York, NY, USA, 15–26 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Settee, P. Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Canada. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability; Nelson, M.K., Shilling, D., Eds.; New Directions in Sustainability and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Redvers, N.; Menzel, K.; Carroll, D.; Zavaleta, C.; Kokunda, S.; Kobei, D.M.; Rojas, J.N. The conceptualization of health and well-being through Indigenous Peoples and their Indigenous Traditional Medicine Systems. Bull. World Health Organ. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Team. WHO traditional medicine global summit 2023 meeting report: Gujarat declaration. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2023, 14, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planetary Health Alliance. What is Planetary Health? Available online: https://planetaryhealthalliance.org/what-is-planetary-health/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Tu’itahi, S.; Watson, H.; Egan, R.; Parkes, M.W.; Hancock, T. Waiora: The importance of Indigenous worldviews and spirituality to inspire and inform Planetary Health Promotion in the Anthropocene. GHP 2021, 28, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; Lindsay, N.M. A commentary on land, health, and Indigenous knowledge(s). Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Lokugamage, A.U.; Barreto, J.P.L.; Bajracharya, M.B.; Harris, M. Epistemicide, health systems, and planetary health: Re-centering Indigenous knowledge systems. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, K. Community archival practice: Indigenous grassroots collaboration at the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. Am. Arch. 2015, 78, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breske, A. Politics of Repatriation: Formalizing Indigenous Repatriation Policy. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2018, 25, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, T.R. Decolonizing Archival Methodology: Combating hegemony and moving towards a collaborative archival environment. Altern. Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2016, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, K.; Hillman, L.; Hillman, L.; Harling, A.R.S.; Talley, B.; McLaughlin, A. Building Sípnuuk: A Digital Library, Archives, and Museum for Indigenous Peoples. Coll. Manag. 2017, 42, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.D. Where Are the Records? In Tribal Libraries, Archives, and Museums: Preserving Our Language, Memory, and Lifeways; Roy, L., Bhasin, A., Arriaga, S.K., Eds.; Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, L.; Alonzo, D. The Record Road: Growing Perspectives on Tribal Archives. In Tribal Libraries, Archives, and Museums: Preserving Our Language, Memory, and Lifeways; Roy, L., Bhasin, A., Arriaga, S.K., Eds.; Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J. ‘Coping and grieving’: An overview of the unprecedented 2023 wildfire season. NNSL. 2023. Available online: https://www.nnsl.com/news/coping-and-grieving-an-overview-of-the-unprecedented-2023-wildfire-season-7274918 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Celidwen, Y.; Redvers, N.; Githaiga, C.; Calambás, J.; Añaños, K.; Chindoy, M.E.; Vitale, R.; Rojas, J.N.; Mondragón, D.; Rosalío, Y.V.; et al. Ethical principles of traditional Indigenous medicine to guide western psychedelic research and practice. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 18, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, K.; Vine, M.M.; Snelling, S.J.; Harris, R.; Smylie, J.; Manson, H. Principles, Approaches, and Methods for Evaluation in Indigenous Contexts: A Grey Literature Scoping Review. CJPE 2019, 34, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; McMillan, F. Reconciliation and Indigenous self-determination in health research: A call to action. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, M.J.; McMillan, F.; Warne, D.; Bennett, B.; Kidd, J.; Williams, N.; Martire, J.L.; Worley, P.; Hutten-Czapski, P.; Saurman, E.; et al. ICIRAS: Research and reconciliation with indigenous peoples in rural health journals. AJRH 2022, 30, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, K.; Haworth-Brockman, M.; Stout, R.; Moffitt, P.; Gelowitz, J.; Schneider, J.; Demczuk, L. Indigenous perspectives on wellness and health in Canada: Study protocol for a scoping review. SR 2020, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, D.; Redvers, N. Protecting and Storing Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Scoping Review. Open Sci. Framew. 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/wyn4h/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia. Available online: http://www.covidence.org (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Redvers, N.; Blondin, B. Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrutia, J.; Anderson, B.T.; Belouin, S.J.; Berger, A.; Griffiths, R.R.; Glob, C.S.; Henningfield, J.E.; Labate, B.C.; Maier, L.J.; Maternowska, M.C.; et al. Psychedelic Science, Contemplative Practices, and Indigenous and Other Traditional Knowledge Systems: Towards Integrative Community-Based Approaches in Global Health. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2023, 55, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 12771288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVivo Software, Lumivero: Denver, Colorado. Available online: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Anderson, J. Access and control of Indigenous knowledge in libraries and archives: Ownership and future use. In Correcting Course: Rebalancing Copyright for Libraries in the National and International Arena; American Library Association: Chicago, IL, USA; The MacArthur Foundation: Chicago, IL, USA; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, E.; Kennedy, P.; MacDonald, W.; Bonaparte, S.; Laszlo, K.; Sinclair, W. Aboriginal Archives Guide; Association of Canadian Archivists: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- First Archivist Circle. Protocols for Native American Archival Materials; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, T. A Drum Speaks: A Partnership to Create a Digital Archive Based on Traditional Ojibwe Systems of Knowledge. RBM 2007, 8, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, R.; LaHache, T.; Whiteduck, T. Digital Data Management as Indigenous Resurgence in Kahnawà:ke. IIPJ 2015, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malsale, P.; Sanau, N.; Tofaeono, T.I.; Kavisi, Z.; Willy, A.; Mitiepo, R.; Lui, S.; Chambers, L.E.; Plotz, R.D. Protocols and Partnerships for Engaging Pacific Island Communities in the Collection and Use of Traditional Climate Knowledge. BAMS 2018, 99, 2471–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Jennings, M.; Jennings, D.; Little, M. Indigenous Data Sovereignty in Action: The Food Wisdom Repository. J. Indig. Wellbeing 2019, 4, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yunes, E.; Itchuaqiyaq, C.U.; Long, K. THE REMATRIATION PROJECT: Building Capacity for Community Digital Archiving in Northwest Alaska. In Proceedings of the iPRES 2023, Champaign, IL, USA, 19–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L.R. Anticolonial Strategies for the Recovery and Maintenance of Indigenous Knowledge. Am. Indian Q. 2004, 28, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.; Dewar, J. Traditional Indigenous Approaches to Healing and the modern welfare of Traditional Knowledge, Spirituality and Lands: A critical reflection on practices and policies taken from the Canadian Indigenous Example. IIPJ 2011, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Nadeau, M.; Prince, D. Urban land-based healing: A northern intervention strategy. Int. J. Indig. Health 2021, 16, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, J. “The land is a healer”: Perspectives on land-based healing from Indigenous practitioners in northern Canada. Int. J. Indig. Health 2020, 15, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, J.; Danto, D.; Walsh, R. Indigenous Grassroots and Family-Run Land-Based Healing in Northern Ontario. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, M. My mother wild: Land and healing for Indigenous youth’s wellness and life transitions. Int. J. Indig. Health 2023, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D.; Mad Plume, L.; Redvers, N. Food access interventions in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: A scoping review. JAFSD 2025, 14, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, R.T.; Grier, A.; Lightning, R.; Mayan, M.J.; Toth, E.L. Cultural continuity, traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta First Nations: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, M.D. Cultural Continuity as a Determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ Health: A Metasynthesis of Qualitative Research in Canada and the United States. IIPJ 2016, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Wexler, L.; Apok, C.A.; Black, J.; Chaliak, J.A.; Cueva, K.; Hollingsworth, C.; McEachern, D.; Peter, E.T.; Ullrich, J.S.; et al. Indigenous Community-Level Protective Factors in the Prevention of Suicide: Enlarging a Definition of Cultural Continuity in Rural Alaska Native Communities. Prev. Sci. 2025, 26, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; McConkey, S.; Beaudoin, E.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J. Mental health and cultural continuity among an urban Indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2024, 115, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums (ATALM). Resources for Native Cultural Institutions. Available online: https://www.atalm.org/programs/current-programs/going-home-returning-material-culture-to-native-communities/resources-for-native-cultural-institutions/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). The First Nations Principles of OCAP. Available online: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/ (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). Barriers and Levers for the Implementation of OCAP. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2014, 5, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Adelson, N.; Mickelson, S. The Miiyupimatisiiun research data archives project: Putting OCAP® principles into practice. Digit. Libr. Perspect. 2022, 38, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.R.; Garba, I.; Figueroa-Rodríguez, O.L.; Holbrook, J.; Lovett, R.; Materechera, S.; Parsons, M.; Raseroka, K.; Rodriguez-Lonebear, D.; Rowe, R.; et al. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci. J. 2020, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.R.; Garba, I.; Plevel, R.; Small-Rodriguez, D.; Hiratsuka, V.Y.; Hudson, M.; Garrison, N.A. Using Indigenous Standards to Implement the CARE Principles: Setting Expectations through Tribal Research Codes. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 823309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, D.; Redvers, N.; McGregor, D. Rebuilding a KINShip Approach to the Climate Crisis: A Comparison of Indigenous Knowledges Policy in Canada and the United States. JISD 2025, 13, 66–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/default.shtml (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Robinson, D.; Raven, M.; Makin, E.; Kalfatak, D.; Hickey, F.; Tari, T. Legal geographies of kava, kastom and indigenous knowledge: Next steps under the Nagoya Protocol. Geoforum 2021, 118, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Medline | “Indigenous knowledge *” OR “traditional knowledge *” AND digitization OR preserv * OR archiv * OR repositor * AND protocol OR guideline * OR template OR “best practice” AND health OR wellness |

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Source type and date | English language; peer reviewed sources, as well as government and organizational sources (e.g., Indigenous government reports), and toolkits. No limit for publication date. |

| Traditional ecological knowledges focus | Indigenous health and wellbeing-related TEK as a concept for this review was used as an “umbrella term” for anything specific or related to health and wellbeing-related ecological knowledges (e.g., food, plants). |

| Population | Documentation is relevant for Indigenous communities with no limits to geographic context. |

| Process of repository development | Documentation addresses the need for and/or the development of a TEK-related repository, and clearly indicates a process for securing and/or moving TEK-related data. |

| Reference | Year | Country | Document Type (* Open Access) | Type of TEK Addressed | Key Findings: Indigenous Repository Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson [36] | 2005 | Australia | Conference proceeding | Ceremonial, traditional medicine | Covers key aspects of Indigenous materials held in non-Indigenous repositories including control, access, and ownership. Also provides case studies and digital aspects (i.e., computer use to access repository) to enhance Indigenous access, and issues of custodianship. |

| Association of Canadian Archivists [37] | 2007 | Canada | Guidance document | Land, language, food | Introductory guidance on archival concepts, basic requirements of archiving, additional general information on assistance and resources. |

| First Archivist Circle at Northern Arizona University [38] | 2007 | United States | Guidance document | Ceremonial, traditional medicine, land | Covers various aspects of archiving Indigenous materials including relationships, intellectual property issues, copyright/repatriation, protocols, reciprocal education, and training. Also provides resources and guidelines for action. |

| Powell [39] | 2007 | United States | Academic journal article | Ceremonial, traditional medicine, plants, land | Provides an overview of key aspects of partnerships to build Indigenous digital archives and discusses lessons learned. |

| McMahon et al. [40] | 2015 | Canada | Academic journal article | Health, land | Covers various aspects of Indigenous digital data management. Also provides a case study of community data management and data governance strategy. |

| Karuk Tribe et al. [19] | 2017 | United States | Academic journal article * | Traditional medicine, food, plants, land | Highlights Indigenous access, control, and repatriation of materials in non-Indigenous repositories. Shares the process of building the Sípnuuk repository including planning, user needs assessment, and establishing protocols and policies for repositories. |

| Malsale et al. [41] | 2018 | Pacific Islands | Academic journal article | Climate, land, plants | Provides a case study example of partnerships that platform Indigenous input including protocols for community engagement to collect and store TEK. Also provides an overview of the legal landscape around TEK. |

| Johnson-Jennings et al. [42] | 2019 | United States | Academic journal article * | Food, plants, land | Outlines key aspects of Indigenous data sovereignty and provides a theoretical framework for developing the Food Wisdom Repository. |

| Yunes et al. [43] | 2023 | United States | Conference proceeding | Land, climate | Provides a case study of building community digital archiving capacity and strategy towards data sovereignty. |

| Category | Sub-Category |

|---|---|

| Impacts on Indigenous health and wellbeing-related TEK repositories | -Impacts of Euro-Western-centric worldviews in archive development and methodologies |

| -Historical trauma and colonization’s effects and impacts on Indigenous health-related TEK repositories | |

| Indigenous knowledges are diverse, living, health-embodying knowledges | -Longstanding cultural protocols and transmission of TEK being a living process |

| -TEK related to health and medicine | |

| Indigenous data concerns around ethics, ownership, use, and governance in the management of TEK archives | -Data ethics, theft, misuse, and expropriation |

| Platforming Indigenous Peoples' access and rights to their data in repositories | -Countering Western data narratives in the governance and management of repositories |

| -Unbalanced power dynamics between Indigenous Peoples and government/settler-colonial institutions affect data repositories | |

| Securing and protecting Indigenous data in an honorable way is important | -Indigenous data ecosystems and worldviews |

| -Indigenous data sovereignty processes, principles, and policies within repositories | |

| Wise practices and challenges in supporting Indigenous-led repository development | -Challenges in the development and maintenance of data repositories |

| -Community access to Indigenous knowledge repositories and processes for consultation | |

| -Decolonizing methodologies and wise practices for Indigenous knowledge repository development |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carroll, D.; Houndolo, M.M.; Big George, A.; Redvers, N. Protecting Repositories of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Health-Focused Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060886

Carroll D, Houndolo MM, Big George A, Redvers N. Protecting Repositories of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Health-Focused Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060886

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarroll, Danya, Mélina Maureen Houndolo, Alia Big George, and Nicole Redvers. 2025. "Protecting Repositories of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Health-Focused Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060886

APA StyleCarroll, D., Houndolo, M. M., Big George, A., & Redvers, N. (2025). Protecting Repositories of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledges: A Health-Focused Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060886