Radical Imagination: An Afrofuturism and Creative Aging Program for Black Women’s Brain Health and Wellness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framework

1.1.1. Afrofuturism

1.1.2. Radical Healing

1.1.3. Creative Aging for Brain Health and Wellness

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Positionality Statements

2.2. Participants and Setting

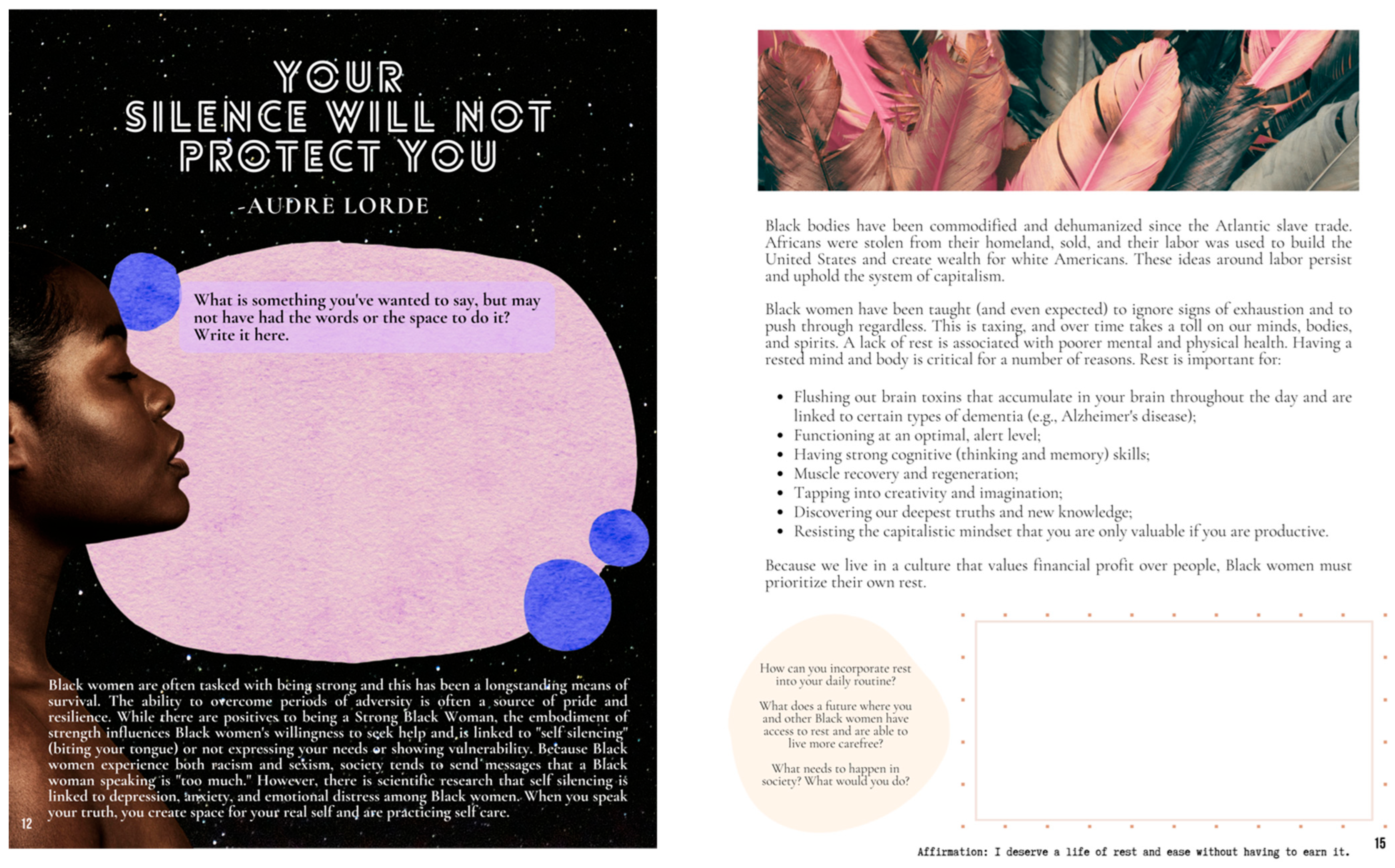

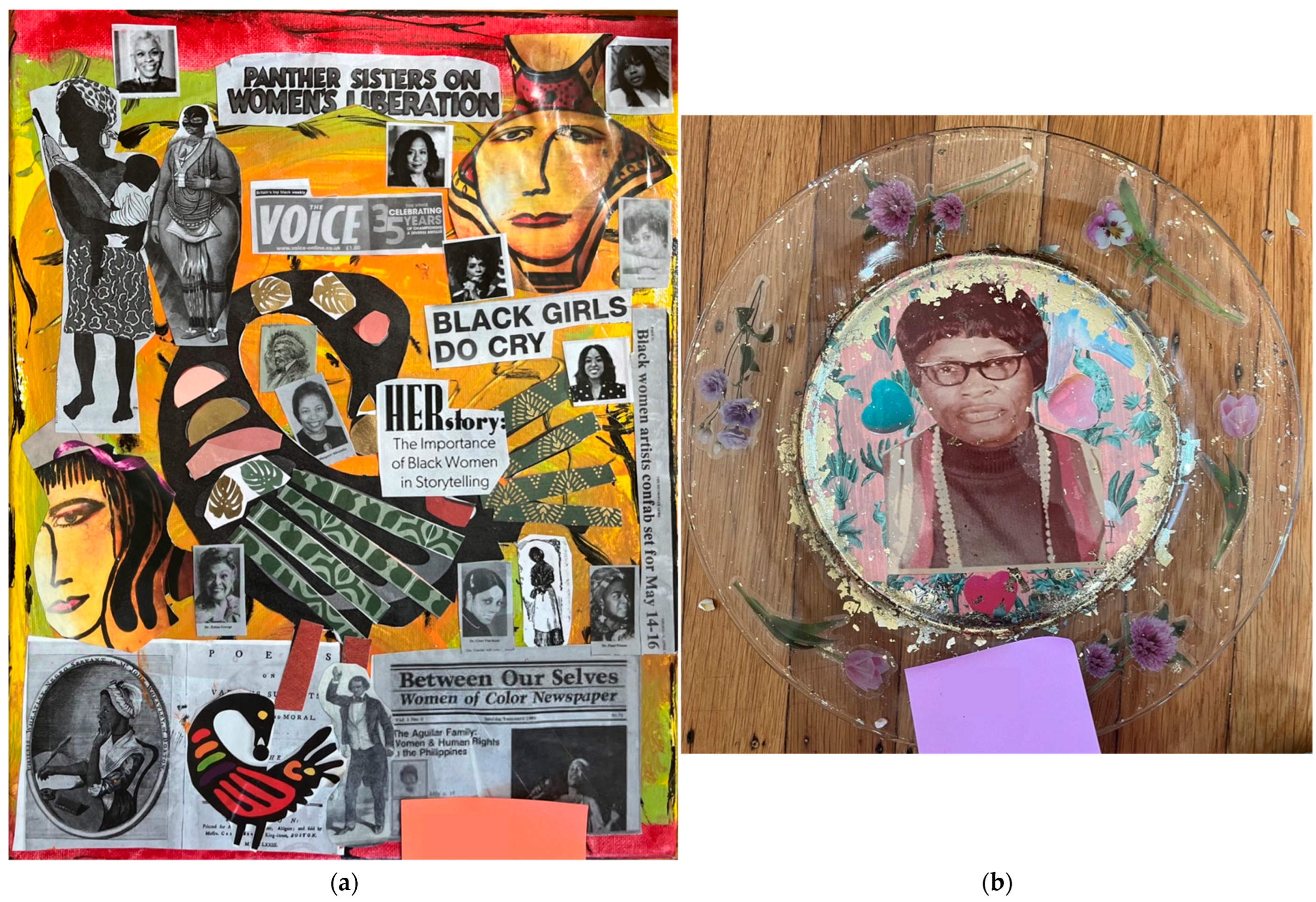

2.3. Program Description

2.4. Data Collection and Analyses

Post-Workshop Survey

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Retention

3.3. Exit Survey

3.3.1. Purpose for Attending

3.3.2. Programming Takeaways

3.3.3. Understanding and Application of Afrofuturism

3.3.4. Overall Interest in Radical Imagination

3.3.5. Recommendations

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, M.K.; Leath, S.; Settles, I.H.; Doty, D.; Conner, K. Gendered Racism and Depression among Black Women: Examining the Roles of Social Support and Identity. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2022, 28, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.A.; Williams, M.G.; Peppers, E.J.; Gadson, C.A. Applying Intersectionality to Explore the Relations between Gendered Racism and Health among Black Women. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.G.; Lewis, J.A. Gendered Racial Microaggressions and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Women: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol. Women Q. 2019, 43, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S.M.; Pasek, J. Intersectional Invisibility Revisited: How Group Prototypes Lead to the Erasure and Exclusion of Black Women. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2020, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, O.N.; Hillman, L.A.; Cernasev, A. Intersectional Invisibility Experiences of Low-Income African-American Women in Healthcare Encounters. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essed, P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-8039-4256-1. [Google Scholar]

- Homan, P.; Brown, T.H.; King, B. Structural Intersectionality as a New Direction for Health Disparities Research. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, A.T.; Lewis, J.A. Gendered Racial Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress Symptoms Among Black Women. Psychol. Women Q. 2019, 43, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Lewis, J.A. Gendered Racism, Coping, Identity Centrality, and African American College Women’s Psychological Distress. Psychol. Women Q. 2016, 40, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.F.; Vonk, J.M.J.; Verney, S.P.; Witkiewitz, K.; Arce Rentería, M.; Schupf, N.; Mayeux, R.; Manly, J.J. Sex/Gender Differences in Cognitive Trajectories Vary as a Function of Race/Ethnicity. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.; Keene, D.; Bound, J. “Weathering” and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores Among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronimus, A.T.; Hicken, M.T.; Pearson, J.A.; Seashols, S.J.; Brown, K.L.; Cruz, T.D. Do US Black Women Experience Stress-Related Accelerated Biological Aging?: A Novel Theory and First Population-Based Test of Black-White Differences in Telomere Length. Hum. Nat. 2010, 21, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, H.O.; Taylor, R.J. Older Black Americans During COVID-19: Race and Age Double Jeopardy. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewe, S.E. The Task Is Far from Completed: Double Jeopardy and Older African Americans. Soc. Work Public Health 2019, 34, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, S.D.; Burnett-Bowie, S.-A.M.; Greendale, G.A.; Avis, N.E.; Reeves, A.N.; Richards, T.R.; Lewis, T.T. Disparities in Reproductive Aging and Midlife Health between Black and White Women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Womens Midlife Health 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Cintron, D.W.; Sims, K.D.; Mayeda, E.R.; Whitmer, R.A.; Gilsanz, P.; Mungas, D.; Glymour, M.M. Evaluating Measurement Invariance of the Everyday Discrimination Scale Among Older Black Men and Women. University of California, SF, USA. 2025. (In preparation) [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Jones, M.K. Gendered Racism and Subjective Cognitive Complaints among Older Black Women: The Role of Depression and Coping. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 36, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D.M.; Rosario, R.J.; Hernandez, I.A.; Destin, M. The Ongoing Development of Strength-Based Approaches to People Who Hold Systemically Marginalized Identities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 27, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, Q.L.; Oyewuwo-Gassikia, O.B. The Case for #BlackGirlMagic: Application of a Strengths-Based, Intersectional Practice Framework for Working with Black Women with Depression. Affilia 2017, 32, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- French, B.H.; Lewis, J.A.; Mosley, D.V.; Adames, H.Y.; Chavez-Dueñas, N.Y.; Chen, G.A.; Neville, H.A. Toward a Psychological Framework of Radical Healing in Communities of Color. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 48, 14–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. Race Against Time: Afrofuturism and Our Liberated Housing Futures. Crit. Anal. Law 2022, 9, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dery, M. (Ed.) Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8223-1531-5. [Google Scholar]

- Haenfler, R. Afrofuturism. Subcultures Soc. 2024. Available online: https://oldsitecopy.haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/afrofuturism/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Dando, M.B.; Holbert, N.; Correa, I. Remixing Wakanda: Envisioning Critical Afrofuturist Design Pedagogies. In Proceedings of the FabLearn, New York, NY, USA, 9 March 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 156–159. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B.D.; Hall, J.L.; O’Flynn, J.; Van Thiel, S. The Future of Public Administration Research: An Editor’s Perspective. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharff, D.P.; Mathews, K.J.; Jackson, P.; Hoffsuemmer, J.; Martin, E.; Edwards, D. More than Tuskegee: Understanding Mistrust about Research Participation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2010, 21, 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Y.R.; Johnson, A.M.; Newman, L.A.; Greene, A.; Johnson, T.R.B.; Rogers, J.L. Perceptions of Clinical Research Participation among African American Women. J. Womens Health 2007, 16, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, 1st ed.; Harlem Moon: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-7679-1547-2. [Google Scholar]

- Eseonu, T.; Okoye, F. Making a Case for Afrofuturism as a Critical Qualitative Inquiry Method for Liberation. Public Integr. 2023, 26, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Jarrett, T.G. The Black Radical Imagination: A Space of Hope and Possible Futures. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1241922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solórzano, D.G.; Yosso, T.J. Critical Race Methodology: Counter-Storytelling as an Analytical Framework for Education Research. Qual. Inq. 2002, 8, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. Black Quantum Futurism: Theory & Practice; Black Quantum Futurism; AfroFuturist Affair, House of Future Science Books: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-9960050-3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R. Spinning the Arrow of Time Studies in Search of New Directions. Time Soc. 2022, 31, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.C. Afrofuturism and the Technologies of Survival. Afr. Arts 2017, 50, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Is Afrofuturism the Socio-Political Movement We’ve Been Building? The Griot. 2021. Available online: https://thegrio.com/2021/08/02/afrofuturism-socio-political-movement/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Watts, R.J. Integrating Social Justice and Psychology. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 32, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioneso, N.A.; Hunter, C.D.; Gobin, R.L.; McNeil Smith, S.; Mendenhall, R.; Neville, H.A. Community Healing and Resistance Through Storytelling: A Framework to Address Racial Trauma in Africana Communities. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8264-1276-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lear, J. Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-674-02746-6. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, H.A. The Role of Counseling Centers in Promoting Wellbeing and Social Justice. In Proceedings of the Big Ten Counseling Center Conference, Champaign, IL, USA, February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. All About Love: New Visions, 1st ed.; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-06-095947-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being?: A Scoping Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; ISBN 978-92-890-5455-3. [Google Scholar]

- Klimczuk, A. Creative Aging: Drawing on the Arts to Enhance Healthy Aging. In Encyclopedia of Geropsychology; Pachana, N.A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-981-287-080-3. [Google Scholar]

- Swadling, C. Creative Ageing—It’s All in Your Mind. Hippocampus 2022. Available online: https://www.newcastle.edu.au/hippocampus/story/2022/creative-ageing-its-all-in-your-mind (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Johnson, J.K.; Stewart, A.L.; Acree, M.; Nápoles, A.M.; Flatt, J.D.; Max, W.B.; Gregorich, S.E. A Community Choir Intervention to Promote Well-Being Among Diverse Older Adults: Results From the Community of Voices Trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, C.M.; Yoshizaki-Gibbons, H.M.; Morhardt, D. The Memory Ensemble: Improvising Connections among Performance, Disability, and Ageing. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2017, 22, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jünemann, K.; Marie, D.; Worschech, F.; Scholz, D.S.; Grouiller, F.; Kliegel, M.; Van De Ville, D.; James, C.E.; Krüger, T.H.C.; Altenmüller, E.; et al. Six Months of Piano Training in Healthy Elderly Stabilizes White Matter Microstructure in the Fornix, Compared to an Active Control Group. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 817889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, G.D.; Perlstein, S.; Chapline, J.; Kelly, J.; Firth, K.M.; Simmens, S. The Impact of Professionally Conducted Cultural Programs on the Physical Health, Mental Health, and Social Functioning of Older Adults. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, B.; Das, A.; Maguire, S.; Fleet, G.; Punamiya, A. The Little Intervention That Could: Creative Aging Implies Healthy Aging among Canadian Seniors. Aging Ment. Health 2024, 28, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noice, T.; Noice, H.; Kramer, A.F. Participatory Arts for Older Adults: A Review of Benefits and Challenges. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herholz, S.C.; Herholz, R.S.; Herholz, K. Non-Pharmacological Interventions and Neuroplasticity in Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.Y.; Schlaug, G. Music Making as a Tool for Promoting Brain Plasticity across the Life Span. Neuroscientist 2010, 16, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Antonietti, A.; Daneau, B. The Relationships Between Cognitive Reserve and Creativity. A Study on American Aging Population. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y.; Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Belleville, S.; Cantilon, M.; Chetelat, G.; Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Kempermann, G.; Kremen, W.S.; et al. Whitepaper: Defining and Investigating Cognitive Reserve, Brain Reserve, and Brain Maintenance. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, A.; Beaty, R.; Silvia, P.; Spreng, R.N.; Turner, G.R. Creative Aging: Functional Brain Networks Associated with Divergent Thinking in Older and Younger Adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 75, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, L.; Chalavi, S.; Swinnen, S.P. Aging and Brain Plasticity. Aging 2018, 10, 1789–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, F.H.D.G.; Fox, A.M.; Tusch, E.S.; Sorond, F.; Mohammed, A.H.; Daffner, K.R. In Vivo Evidence for Neuroplasticity in Older Adults. Brain Res. Bull. 2015, 114, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeda, E.R.; Glymour, M.M.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Whitmer, R.A. Inequalities in Dementia Incidence between Six Racial and Ethnic Groups over 14 Years. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.-X.; Cross, P.; Andrews, H.; Jacobs, D.M.; Small, S.; Bell, K.; Merchant, C.; Lantigua, R.; Costa, R.; Stern, Y.; et al. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in Northern Manhattan. Neurology 2001, 56, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, C.R.; Kaneshiro, C.; Jang, J.Y.; Reynolds, C.A.; Pedersen, N.L.; Gatz, M. Differences Between Women and Men in Incidence Rates of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 64, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonke, J.; Golden, T.; Francois, S.; Hand, J.; Chandra, A.; Clemmons, L.; Fakunle, D.; Jackson, M.R.; Magsamen, S.; Rubin, V.; et al. Creating Healthy Communities through Cross-Sector Collaboration [White Paper]. 2019. Available online: https://arts.ufl.edu/site/assets/files/174533/uf_chc_whitepaper_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Wiseman, J.; Brasher, K. Community Wellbeing in an Unwell World: Trends, Challenges, and Possibilities. J. Public Health Policy 2008, 29, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engh, R.; Martin, B.; Laramee Kidd, S.; Gadwa Nicodemus, A. WE-Making: How Arts & Culture Unite People to Work toward Community Well-Being; Metris Arts Consulting: Easton, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Secules, S.; McCall, C.; Mejia, J.A.; Beebe, C.; Masters, A.S.; Sanchez-Pena, M.L.; Svyantek, M. Positionality Practices and Dimensions of Impact on Equity Research: A Collaborative Inquiry and Call to the Community. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, T. Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto, 1st ed.; Little, Brown Spark: New York, NY, USA; Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-316-36521-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Jarrett, T.; Henderson, A.J. The Other Side of Time. 2023. Available online: https://www.tanishahilljarrett.com/othersideoftime (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooks, B. Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness. Framew. J. Cine. Media 2022, 10, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.B.; Varma, V.R.; Pettigrew, C.; Albert, M.S. African Americans and Clinical Research: Evidence Concerning Barriers and Facilitators to Participation and Recruitment Recommendations. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcantonio, E.R.; Aneja, J.; Jones, R.N.; Alsop, D.C.; Fong, T.G.; Crosby, G.J.; Culley, D.J.; Cupples, L.A.; Inouye, S.K. Maximizing Clinical Research Participation in Vulnerable Older Persons: Identification of Barriers and Motivators. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomida, K.; Shimoda, T.; Nakajima, C.; Kawakami, A.; Shimada, H. Social Isolation/Loneliness and Mobility Disability Among Older Adults. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2024, 13, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, L.B.; Solway, E.S.; Malani, P.N. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. JAMA 2024, 331, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K.; Ghesquiere, A.; Glickman, K. Bereavement and Complicated Grief. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reher, D.; Requena, M. Living Alone in Later Life: A Global Perspective. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2018, 44, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elovainio, M.; Lahti, J.; Pirinen, M.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Malmberg, A.; Lipsanen, J.; Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Hakulinen, C. Association of Social Isolation, Loneliness and Genetic Risk with Incidence of Dementia: UK Biobank Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Tamayo, K.; Manrique-Espinoza, B.; Ramírez-García, E.; Sánchez-García, S. Social Isolation Undermines Quality of Life in Older Adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugesen, K.; Baggesen, L.M.; Schmidt, S.A.J.; Glymour, M.M.; Lasgaard, M.; Milstein, A.; Sørensen, H.T.; Adler, N.E.; Ehrenstein, V. Social Isolation and All-Cause Mortality: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Denmark. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachón-Alonso, L.; Hakulinen, C.; Jokela, M.; Komulainen, K.; Elovainio, M. Loneliness and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: Longitudinal Analysis in 15 Countries. Psychol. Aging 2023, 38, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, N.J.; Wu, Q.; Rentz, D.M.; Sperling, R.A.; Marshall, G.A.; Glymour, M.M. Loneliness, Depression and Cognitive Function in Older U.S. Adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadswell, A.; Bungay, H.; Wilson, C.; Munn-Giddings, C. The Impact of Participatory Arts in Promoting Social Relationships for Older People within Care Homes. Perspect. Public Health 2020, 140, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadswell, A.; Wilson, C.; Bungay, H.; Munn-Giddings, C. The Role of Participatory Arts in Addressing the Loneliness and Social Isolation of Older People: A Conceptual Review of the Literature. J. Arts Communities 2017, 9, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remm, S.; Halcomb, E.; Hatcher, D.; Frost, S.A.; Peters, K. Understanding Relationships between General Self-efficacy and the Healthy Ageing of Older People: An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmele, U.; Ballhausen, N.; Ihle, A.; Kliegel, M. In Older Adults, Perceived Stress and Self-Efficacy Are Associated with Verbal Fluency, Reasoning, and Prospective Memory (Moderated by Socioeconomic Position). Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.K.; Akram, S.; Colverson, A.J.; Hack, G.; Golden, T.L.; Sonke, J. Arts Engagement as a Health Behavior: An Opportunity to Address Mental Health Inequities. Community Health Equity Res. Policy 2024, 44, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioranelli, M.; Roccia, M.G.; Garo, M.L. The Role of Arts Engagement in Reducing Cognitive Decline and Improving Quality of Life in Healthy Older People: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1232357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A. Community Group Membership and Multidimensional Subjective Well-Being in Older Age. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.D. Future Orientation and Health Among Older Adults: The Importance of Hope. Educ. Gerontol. 2014, 40, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, O. Black Scholar Interview with Octavia Butler: Black Women and the Science Fiction Genre. Black Sch. 1986, 17, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tosaya, L.C. Gender and Race in Science Fiction and the Emergence of Afrofuturism. Masters Thesis, California State University, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- West, C. Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire, and Their Homegirls: Developing an “Oppositional” Gaze toward the Images of Black Women. In Lectures on the Psychology of Women; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers, R.J.; Mustafaa, F.N.; Noel, B. Cultural Integrity and African American Empowerment: Insights and Practical Implications for Community Psychology. In APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Methods for Community Research and Action for Diverse Groups and Issues; Bond, M.A., Serrano-García, I., Keys, C.B., Shinn, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 459–474. ISBN 978-1-4338-2260-5. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, M.W.; Galarza, A.; Todman, L.C. Ethnic–Racial Identity Latent Profiles Protect against Racial Discrimination in Black American Adults. J. Couns. Psychol. 2024, 71, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, R.M.; Copeland-Linder, N.; Martin, P.P.; Lewis, R.L. Racial Identity Matters: The Relationship between Racial Discrimination and Psychological Functioning in African American Adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.M.; Jones, M.K. Black Women at War: A Comprehensive Framework for Research on the Strong Black Woman. Womens Stud. Commun. 2021, 44, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spates, K.; Evans, N.M.; Watts, B.C.; Abubakar, N.; James, T. Keeping Ourselves Sane: A Qualitative Exploration of Black Women’s Coping Strategies for Gendered Racism. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.N.; Hunter, C.D. “I Had To Be Strong”: Tensions in the Strong Black Woman Schema. J. Black Psychol. 2016, 42, 424–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.K.; Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Latimer, K.; Reynolds, A.; Garrett, N.; Harris, I.; Joseph, S.; Jones, A. The Role of Coping in the Relationship Between Endorsement of the Strong Black Woman Schema and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Women. J. Black Psychol. 2021, 47, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.A.; Maxwell, M.; Pope, M.; Belgrave, F.Z. Carrying the World With the Grace of a Lady and the Grit of a Warrior: Deepening Our Understanding of the “Strong Black Woman” Schema. Psychol. Women Q. 2014, 38, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Thomas, M.D.; Michaels, E.K.; Reeves, A.N.; Okoye, U.; Price, M.M.; Hasson, R.E.; Syme, S.L.; Chae, D.H. Racial Discrimination, Educational Attainment, and Biological Dysregulation among Midlife African American Women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 99, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant, T. You Have to Show Strength: An Exploration of Gender, Race, and Depression. Gend. Soc. 2007, 21, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Singleton, N.N. Strong Black Woman Schema and Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Perceived Emotional Support. J. Black Psychol. 2017, 43, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Superwoman Schema: African American Women’s Views on Stress, Strength, and Health. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.L.J.E.; Nkomo, S.M. Armoring: Leaming to Withstand Racial Oppression. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 1998, 29, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambley-Ebron, D.; Dole, D.; Karikari, A. Cultural Preparation for Womanhood in Urban African American Girls: Growing Strong Women. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 27, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.J.; King, C.T. Gendered Racial Socialization of African American Mothers and Daughters. Fam. J. 2007, 15, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, V. Stronger: An Examination of the Effects of the Strong Black Woman Narrative through the Lifespan of African American Women. Masters Thesis, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Gender, Black Feminism, and Black Political Economy. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2000, 568, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M. Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman; Verso: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-78168-821-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.A.; Kenny, R.A. “I’m Too Old for That”—The Association between Negative Perceptions of Aging and Disengagement in Later Life. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 100, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Leon, R. Afro- and Age-Futurism: Imagining a Better Future for All Elders. Gener. Today 2021. Available online: https://generations.asaging.org/afro-and-age-futurism-better-future-elders (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Dei, G.J.S.; Karanja, W.; Erger, G. Making the Case for the Incorporation of African Indigenous Elders and Their Cultural Knowledges into Schools. In Elders’ Cultural Knowledges and the Question of Black/African Indigeneity in Education; Critical Studies of Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 16, pp. 153–174. ISBN 978-3-030-84200-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J. The Human Imagination: The Cognitive Neuroscience of Visual Mental Imagery. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacter, D.L.; Addis, D.R.; Hassabis, D.; Martin, V.C.; Spreng, R.N.; Szpunar, K.K. The Future of Memory: Remembering, Imagining, and the Brain. Neuron 2012, 76, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousanis, N. Unflattening; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-674-74443-1. [Google Scholar]

| Workshop (Number of Attendees) | Purpose and Overview | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Welcome and orientation (n = 21) |

|

|

| 2: Sankofa (“Go back to the past and bring forward that which is useful.”) (n = 26) |

|

|

| 3: Legacy (n = 21) |

|

|

| 4: Affirmations from the future (n = 17) |

|

|

| 5: Black woman utopias (n = 17) |

|

|

| 6: The art of adornment (n = 18) |

|

|

| 7: Brain health education and common misconceptions (n = 17) |

|

|

| 8a: Shaping possible futures (n = 20) |

|

|

| 8b: We will rest (n = 14) |

|

|

| 9: Celebration and reflection (n = 17) |

|

|

| 10: Photoshoot: The Other Side of Time (n = 13) |

|

|

| Question | Very Untrue | Somewhat Untrue | Neutral | Somewhat True | Very True |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The topics discussed were interesting. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.30 | 12.5 | 81.3 |

| I learned about topics important for Black women. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.5 | 6.30 | 81.3 |

| I feel confident explaining Afrofuturism and its importance for Black women. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.5 | 29.4 | 47.1 |

| I am hopeful about my ability to shape the future. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.60 | 33.3 | 61.1 |

| The art activities in each class were interesting. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.5 | 87.5 |

| I am satisfied with the workshop series. | 0.00 | 5.60 | 0.00 | 22.2 | 72.2 |

| I would attend another workshop in the future. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.60 | 11.1 | 83.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Jackson, A.J.; Amuiri, A.; Aguirre, G.A. Radical Imagination: An Afrofuturism and Creative Aging Program for Black Women’s Brain Health and Wellness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060875

Hill-Jarrett TG, Jackson AJ, Amuiri A, Aguirre GA. Radical Imagination: An Afrofuturism and Creative Aging Program for Black Women’s Brain Health and Wellness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060875

Chicago/Turabian StyleHill-Jarrett, Tanisha G., Ashley J. Jackson, Alinda Amuiri, and Gloria A. Aguirre. 2025. "Radical Imagination: An Afrofuturism and Creative Aging Program for Black Women’s Brain Health and Wellness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060875

APA StyleHill-Jarrett, T. G., Jackson, A. J., Amuiri, A., & Aguirre, G. A. (2025). Radical Imagination: An Afrofuturism and Creative Aging Program for Black Women’s Brain Health and Wellness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060875