Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Mortality Among Individuals with Suicidal Ideation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures: Mortality

2.3. Measures: Suicidal Ideation and CRC

2.4. Measures: Comorbid Conditions

2.5. Measures: Additional Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

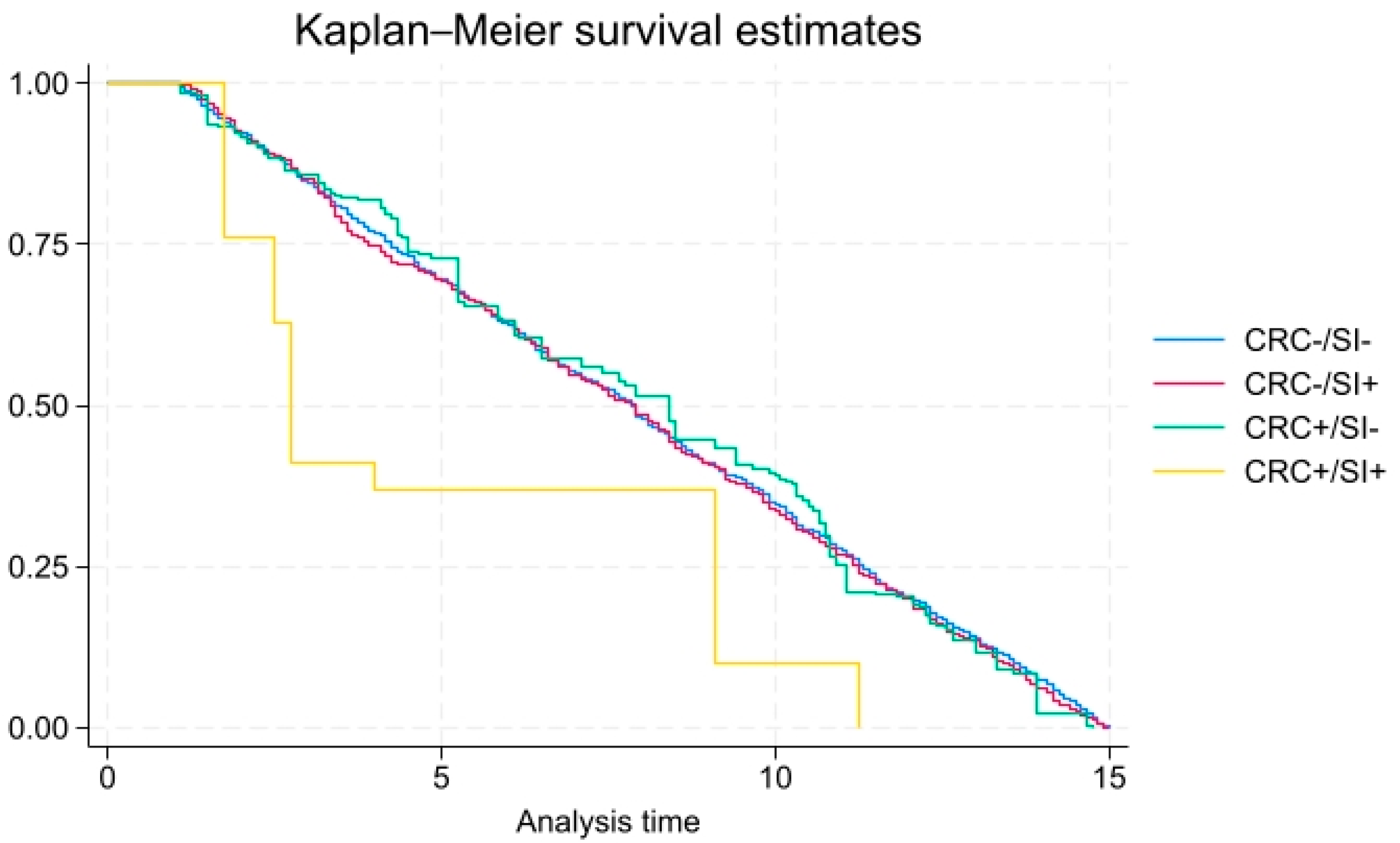

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2024 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/programs/prevention-and-wellness/mental-health-substance-abuse/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/index.html (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control. Suicide Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Martínez-Alés, G.; Jiang, T.; Keyes, K.M.; Gradus, J.L. The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2022, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.; Singer, D.; Carpinella, C.M.; Shawi, M.; Alphs, L. The health-related quality of life, work productivity, healthcare resource utilization, and economic burden associated with levels of suicidal ideation among patients self-reporting moderately severe or severe major depressive disorder in a national survey. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.; Haileyesus, T.; Stone, D.M. Economic cost of US suicide and nonfatal self-harm. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadis, H.M.; D’Aiuto, C.; Lamoureux-Lamarche, C.; Pitrou, I.; Gontijo Guerra, S.; Berbiche, D. Pain, functional disability, and mental disorders as potential mediators of the association between chronic physical conditions and suicidal ideation in community-living older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. Suicides among non-elderly adult Hispanics, 2010–2020. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.L.; Joiner, T.E.; Shahar, G. Suicidality in chronic illness: An overview of cognitive–affective and interpersonal factors. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2021, 28, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, K.M.; Duffy, M.; Kennedy, G.; Stentz, L.; Leon, J.; Herrerias, G.; Fulcher, S.; Joiner, T.E. Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death among Veterans and service members: A comprehensive meta-analysis of risk factors. Mil. Psychol. 2022, 34, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samawi, H.H.; Shaheen, A.A.; Tang, P.A.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Cheung, W.Y.; Vickers, M.M. Risk and predictors of suicide in colorectal cancer patients: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, e513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favril, L.; Yu, R.; Uyar, A.; Sharpe, M.; Fazel, S. Risk factors for suicide in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies. BMJ Ment. Health 2022, 25, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoun, F.; Elshiwy, K.; Elkeraie, Y.; Merjaneh, Z.; Khoudari, G.; Sarmini, M.T.; Gad, M.; Al-Husseini, M.; Saad, A. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: Recent trends and impact on outcomes. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khubchandani, J.; Banerjee, S.; Gonzales-Lagos, R.; Kopera-Frye, K. Food Insecurity Is Associated with a Higher Risk of Mortality among Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Karuniawati, H.; Jairoun, A.A.; Urbi, Z.; Ooi, D.J.; John, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Kibria, K.M.K.; Mohiuddin, A.K.M.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Colorectal cancer: A review of carcinogenesis, global epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and treatment strategies. Cancers 2022, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, V.; Oveisi, N.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Loree, J.M.; Murphy, R.A.; De Vera, M.A. Colorectal cancer and onset of anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8751–8766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Khubchandani, J.; Tisinger, S.; Batra, K.; Greenway, M. Mortality risk among adult Americans living with cancer and elevated CRP. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024, 90, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.E.; Shrout, M.R.; Madison, A.A.; Alfano, C.M.; Povoski, S.P.; Lipari, A.M.; Carson, W.E., III.; Malarkey, W.B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients: Ties to pain, fatigue, and inflammation. Psycho-Oncol. 2022, 31, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Tworoger, S.S.; Zhang, X.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Kubzansky, L.D. Anxiety, depression, and colorectal cancer survival: Results from two prospective cohorts. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, E.S.; Moazzam, Z.; Woldesenbet, S.; Lima, H.A.; Endo, Y.; Azap, L.; Yang, J.; Dillhoff, M.; Ejaz, A.; Pawlik, T.M.; et al. Suicidal ideation among patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3929–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.M.; Lin, C.L.; Hsu, C.Y.; Kao, C.H. Risk of suicide attempts among colorectal cancer patients: A nationwide population-based matched cohort study. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 2794–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Banerjee, S.; Radak, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Dunn, P. Food insecurity and mortality in American adults: Results from the NHANES-linked mortality study. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonson, M.; Sigström, R.; Van Orden, K.A.; Fässberg, M.M.; Skoog, I.; Waern, M. Life-weariness, wish to die, active suicidal Ideation, and all-cause mortality in population-based samples of older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Park, E.M.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Nichols, H.B. Suicide rates among patients with cancers of the digestive system. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, J.; Emile, S.H.; Wignakumar, A.; Horesh, N.; DeTrolio, V.; Gefen, R.; Garoufalia, Z.; Wexner, S.D. Risk factors for suicide in patients with colorectal cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. Surgery 2025, 178, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, Z.; Ji, X.; Shen, Q.; Tuo, J.; Bi, J.; Li, H.; Xiang, Y. Global pattern and trends of colorectal cancer survival: A systematic review of population-based registration data. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.; de la Croix, H.; Grönkvist, R.; Park, J.; Rosenberg, J.; Tasselius, V.; Angenete, E.; Haglind, E. Suicide after colorectal cancer—A national population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2024, 26, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulskas, A.; Patasius, A.; Kaceniene, A.; Urbonas, V.; Smailyte, G. Suicide risk among colorectal cancer patients in Lithuania. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Talukder, A.M.; Walsh, N.J.; Lawson, A.G.; Jones, A.J.; Bishop, J.L.; Kruse, E.J. Clinical and epidemiological factors associated with suicide in colorectal cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Behnezhad, S. Cancer diagnosis and suicide mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24 (Suppl. 2), S94–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Xie, J.; Duan, Y.; Li, J.; She, Z.; Lu, W.; Chen, Y. The psychological distress of gastrointestinal cancer patients and its association with quality of life among different genders. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.M.; Kim, S.J.; Song, S.K.; Kim, H.R.; Kang, B.D.; Noh, S.H.; Chung, H.C.; Kim, K.R.; Rha, S.Y. Prevalence and prognostic implications of psychological distress in patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tuijl, L.A.; Basten, M.; Pan, K.Y.; Vermeulen, R.; Portengen, L.; de Graeff, A.; Dekker, J.; Geerlings, M.I.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Ranchor, A.V. Depression, anxiety, and the risk of cancer: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Cancer 2023, 129, 3287–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, D.E.; Hanganu, B.; Postolica, R.; Buhas, C.L.; Paparau, C.; Ioan, B.G. Suicide Risk in Digestive Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of Sociodemographic, Psychological, and Clinical Predictors. Cancers 2025, 17, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bausys, A.; Kryzauskas, M.; Abeciunas, V.; Degutyte, A.E.; Bausys, R.; Strupas, K.; Poskus, T. Prehabilitation in modern colorectal cancer surgery: A comprehensive review. Cancers 2022, 14, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total Population (n = 34,276) | CRC (+) (n = 208) | CRC (−) (n = 34,015) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking Status * | |||

| Never smoked | 54.8 (53.8–55.9) | 45.5 (27.7–63.3) | 54.9 (53.9–55.9) |

| Formerly smoked | 25.0 (24.3–25.7) | 40.4 (24.9–56.0) | 24.2 (24.2–25.6) |

| Currently smoke | 20.2 (19.5–20.9) | 14.1 (10.0–18.1) | 20.2 (19.5–20.9) |

| Obesity (yes, 95%CI) | |||

| Obese BMI ≥ 30 | 37.6 (37.0–38.3) | 42.6 (31.5–53.7) | 37.6 (36.9–38.3) |

| Hypertension (yes, 95% CI) ** | 32.2 (31.5–32.8) | 67.9 (62.8–73.1) | 32.0 (31.3–32.7) |

| Diabetes (yes, 95% CI) ** | 11.8 (11.3–12.3) | 25.8 (19.7–32.0) | 11.8 (11.3–12.2) |

| Cardiovascular Disease (yes, 95% CI) ** | 8.6 (8.3–9.0) | 23.2 (17.7–28.6) | 8.5 (8.2–8.9) |

| Suicidal Ideation ** | |||

| Not at all | 96.7 (96.5–96.9) | 93.4 (86.1–97.0) | 96.7 (96.5–96.9) |

| Several days | 2.3 (2.2–2.5) | 2.0 (0.5–8.2) | 2.3 (2.2–2.5) |

| More than half the days | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 2.0 (0.9–4.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

| Nearly every day | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 2.6 (0.6–10.8) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Age (years, SE) ** | 47.5 (0.19) | 66.7 (1.64) | 47.4 (0.19) |

| Gender (Male %, 95% CI) | 48.7 (48.3–49.1) | 46.1 (36.4–55.9) | 48.7 (48.3–49.1) |

| Ethnicity ** | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 67.9 (65.9–69.8) | 82.2 (77.4–87.0) | 67.8 (6.3–67.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.0 (9.7–12.3) | 10.1 (5.6–14.6) | 11.0 (9.7–12.3) |

| Hispanic | 13.8 (12.0–15.6) | 5.1 (3.0–8.5) | 13.9 (12.1–15.7) |

| Other | 7.3 (6.2–8.6) | 2.6 (1.2–5.5) | 7.3 (6.2–8.6) |

| Education Level * | |||

| Some high school | 17.0 (15.8–18.3) | 23.9 (18.3–29.5) | 17.0 (17.9–20.0) |

| High school graduate | 22.2 (21.4–23.1) | 19.1 (12.9–25.3) | 22.3 (21.4–23.1) |

| Some college and beyond | 60.7 (59.7–62.5) | 57.0 (49.4–64.7) | 60.8 (59.0–62.5) |

| PIR < 2 (yes, 95% CI) | 13.8 (13.1–14.4) | 13.7 (10.5–16.9) | 13.8 (13.1–14.4) |

| All deaths (N, %) ** | 3609 (7.7) | 83 (34.6) | 3526 (7.6) |

| Total Population HR (95%CI) CRC vs. No-CRC | SI Without CRC HR (95%CI) | CRC Without SI HR (95%CI) | Both CRC and SI HR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC or SI | 1.39 (1.15–1.70) * | 1.42 (1.16–1.75) * | 1.37 (1.13–1.67) * | 5.40 (1.53–19.02) ** |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never smoked | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Formerly smoked | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) * | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) ** | 1.21 (1.09–1.34) ** | 0.83 (0.38–1.83) |

| Currently smoke | 2.25 (2.03–2.49) ** | 2.25 (2.03–2.49) ** | 2.25 (2.04–2.49) ** | 1.65 (0.97–2.81) |

| Obesity (yes vs. no) | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 1.04 (0.72–1.50) |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 1.23 (1.12–1.34) ** | 1.23 (1.12–1.35) ** | 1.22 (1.11–1.33) ** | 1.62 (1.02–2.57) * |

| Diabetes (yes vs. no) | 1.47 (1.37–1.58) ** | 1.48 (1.36–1.56) ** | 1.48 (1.38–1.59) ** | 1.15 (0.81–1.62) |

| CVD (yes vs. no) | 1.71 (1.54–1.89) ** | 1.71 (1.55–1.87) ** | 1.74 (1.58–1.92) ** | 1.01 (0.71–1.44) |

| Age | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) ** | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) ** | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) ** | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) ** |

| Gender (ref. female) | 1.31 (1.21–1.41) ** | 1.31 (1.21–1.41) ** | 1.32 (1.21–1.44) ** | 1.22 (0.79–1.90) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) * | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 1.01 (0.92–1.12) | 0.85 (0.51–1.41) |

| Hispanic | 0.64 (0.55–0.75) ** | 0.64 (0.54–0.74) ** | 0.66 (0.57–0.78) ** | 0.36 (0.22–0.60) ** |

| Other | 0.68 (0.54–0.85) * | 0.68 (0.55–0.86) | 0.69 (0.55–0.87) * | 0.37 (0.17–0.80) * |

| Education Level | ||||

| Some college or beyond | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some high school | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) * | 1.33 (1.10–1.60) * | 1.31 (1.07–1.59) * | 1.13 (0.81–1.58) |

| High school graduate | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) ** | 1.23 (1.11–1.37) ** | 1.24 (1.10–1.39) ** | 0.93 (0.62–1.41) |

| PIR ≥ 2 | 1.72 (1.53–1.94) ** | 1.70 (1.51–1.90) ** | 1.69 (1.52–1.88) ** | 2.16 (1.54–3.02) ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banerjee, S.; Khubchandani, J.; Nkemjika, S. Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Mortality Among Individuals with Suicidal Ideation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060862

Banerjee S, Khubchandani J, Nkemjika S. Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Mortality Among Individuals with Suicidal Ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060862

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanerjee, Srikanta, Jagdish Khubchandani, and Stanley Nkemjika. 2025. "Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Mortality Among Individuals with Suicidal Ideation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060862

APA StyleBanerjee, S., Khubchandani, J., & Nkemjika, S. (2025). Colorectal Cancer and the Risk of Mortality Among Individuals with Suicidal Ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060862