Systematic Evaluation of How Indicators of Inequity and Disadvantage Are Measured and Reported in Population Health Evidence Syntheses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening

2.4. Outcome Selection

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

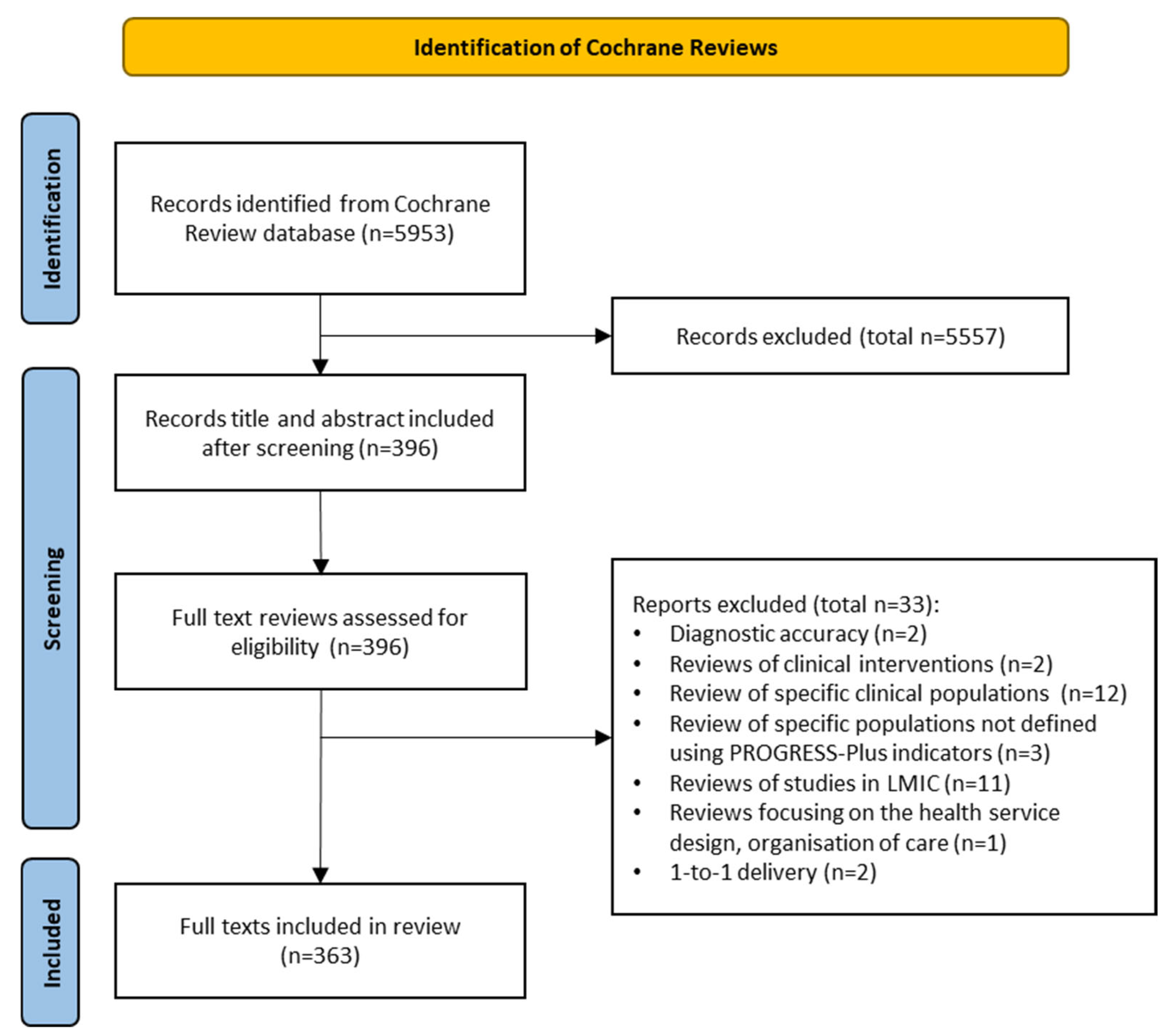

3.1. Results of Screening

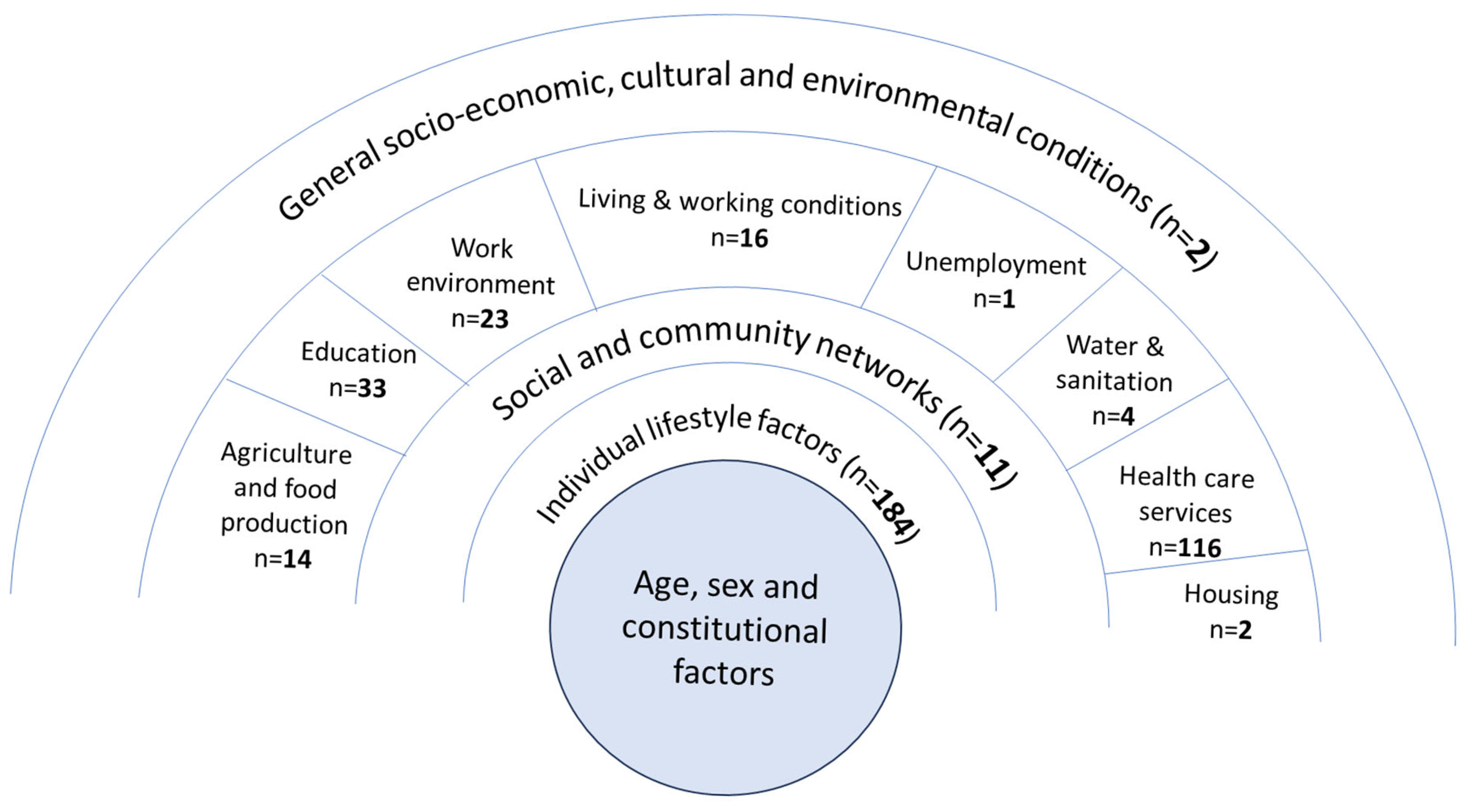

3.2. Characteristics of Reviews

3.3. Measurement and Reporting of Health Inequities or Inequalities

3.4. Use of PROGRESS/PROGRESS-Plus

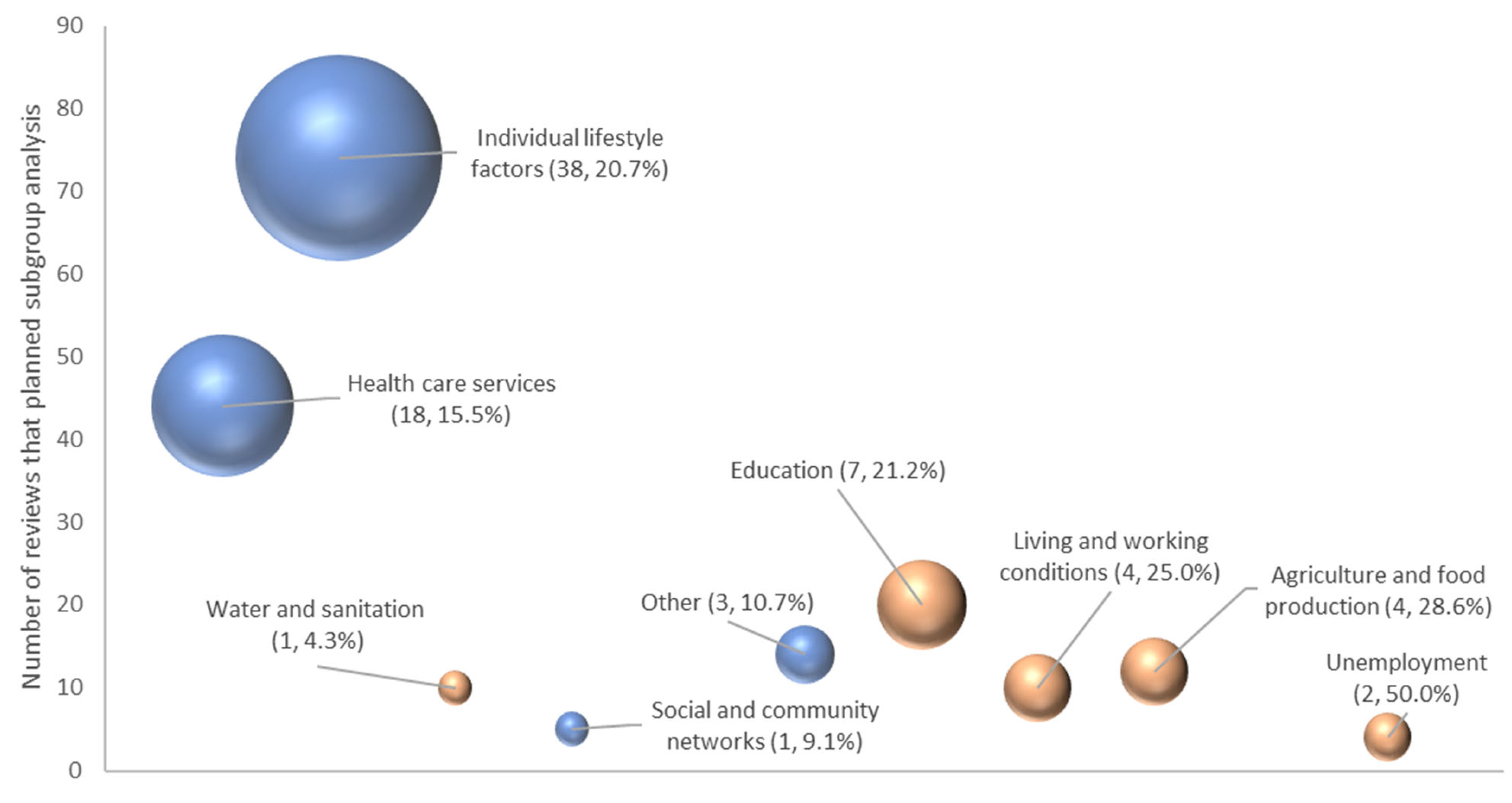

3.5. Subgroup Analysis by PROGRESS-Plus Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frohlich, K.L.; Potvin, L. Transcending the known in public health practice: The inequality paradox: The population approach and vulnerable populations. Am. J. Public. Health 2008, 98, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, V.; Petkovic, J.; Hartling, L.; Klassen, T.; Kristjansson, E.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Petticrew, M.; Stott, D.; Thomson, D.; Ueffing, E.; et al. Chapter 16: Equity and Specific Populations. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Porroche-Escudero, A.; Popay, J. The Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting integration of equity into applied health research. J. Public. Health 2021, 43, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, A.V. On the Distinction-or Lack of Distinction-Between Population Health and Public Health. Am. J. Public. Health 2016, 106, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Montoya, J. The practical irrelevance of distinguishing between public health and population health. Rev. De La Univ. Ind. De Santander. Salud 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.A.; Khaw, K.-T.; Marmot, M. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine: The Complete Original Text; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rukmana, D. Vulnerable Populations. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6989–6992. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Goldblatt, P.; Boyce, T.; Di McNeish, M.; Grady, I.G. Fair Society, Health Lives: The Marmot Review. In Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010; Insititute of Health Equity, University College London: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arcaya, M.C.; Arcaya, A.L.; Subramanian, S.V. Inequalities in health: Definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 27106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Handbook on Health Inequality Monitoring: With a Special Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Almeida-Filho, N. A glossary for health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; O’Neill, J.; Waters, E.; White, H.; PRISMA-Equity Bellagio Group. PRISMA-Equity 2012 Extension: Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews with a Focus on Health Equity. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Nambiar, D.; Schlotheuber, A.; Reidpath, D.; Ross, Z. Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT): Software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Petkovic, J.; Moher, D.; Waters, E.; White, H.; Tugwell, P.; Atun, R.; Awasthi, S.; Barbour, V.; et al. Extending the PRISMA statement to equity-focused systematic reviews (PRISMA-E 2012): Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 70, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, T.; Raymond, A.; Rachet-Jacquet, L. Quantifying Health Inequalities in England; The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Glasziou, P.; Sanders, S. Investigating causes of heterogeneity in systematic reviews. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavis, J.N.; Røttingen, J.-A.; Bosch-Capblanch, X.; Atun, R.; El-Jardali, F.; Gilson, L.; Lewin, S.; Oliver, S.; Ongolo-Zogo, P.; Haines, A. Guidance for evidence-informed policies about health systems: Linking guidance development to policy development. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M.; Graham, H.; Macintyre, S.J.; Bambra, C.; Egan, M. Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 2: Assembling the evidence jigsaw. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugwell, P.; Petticrew, M.; Kristjansson, E.; Welch, V.; Ueffing, E.; Waters, E.; Bonnefoy, J.; Morgan, A.; Doohan, E.; Kelly, M.P. Assessing equity in systematic reviews: Realising the recommendations of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. BMJ 2010, 341, c4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Brown, H. Road traffic crashes: Operationalizing equity in the context of health sector reform. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2003, 10, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, J.; Oliver, S.; Lorenc, T. Reflections on developing and using PROGRESS-Plus Equity Update. Equity Update Cochrane Health Equity Methods Group 2008, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hollands, G.J.; South, E.; Shemilt, I.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J.; Sowden, A.J. Methods used to conceptualize dimensions of health equity impacts of public health interventions in systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2024, 169, 111312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunonga, T.P.; Hanratty, B.; Bower, P.; Craig, D. A systematic review finds a lack of consensus in methodological approaches in health inequality/inequity focused reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 156, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, V.; Dewidar, O.; Tanjong Ghogomu, E.; Abdisalam, S.; Al Ameer, A.; Barbeau, V.I.; Brand, K.; Kebedom, K.; Benkhalti, M.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. How effects on health equity are assessed in systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 1, MR000028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, D.; Retzer, A.; Ahmed, K.; Keeley, T.; Armes, J.; Brown, J.M.; Calman, L.; Gavin, A.; Glaser, A.W.; Greenfield, D.M.; et al. Systematic Evaluation of Patient-Reported Outcome Protocol Content and Reporting in Cancer Trials. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Devane, D.; Begley, C.M.; Clarke, M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.D.; Galobardes, B.; Matijasevich, A.; Gordon, D.; Johnston, D.; Onwujekwe, O.; Patel, R.; Webb, E.A.; Lawlor, D.A.; Hargreaves, J.R. Measuring socio-economic position for epidemiological studies in low- and middle-income countries: A methods of measurement in epidemiology paper. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Background Document to WHO-Strategy Paper for Europe; Institute for Future Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hombali, A.S.; Solon, J.A.; Venkatesh, B.T.; Nair, N.S.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Fortification of staple foods with vitamin A for vitamin A deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 5, CD010068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lhachimi, S.K.; Pega, F.; Heise, T.L.; Fenton, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Griebler, U.; Sommer, I.; Bombana, M.; Katikireddi, S. Taxation of the fat content of foods for reducing their consumption and preventing obesity or other adverse health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD012415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pega, F.; Carter, K.; Blakely, T.; Lucas, P.J. In-work tax credits for families and their impact on health status in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD009963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfindern, M.; Heisen, T.L.; Hiltonn Boon, M.; Pega, F.; Fenton, C.; Griebler, U.; Gartlehner, G.; Sommer, I.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Lhachimi, S.K. Taxation of unprocessed sugar or sugar-added foods for reducing their consumption and preventing obesity or other adverse health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD012333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.H.M.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; Elwenspoek, M.; Foxen, S.C.; Magee, L.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Davison, C.M.; Ufholz, L.A.; Freeman, J.; Shankar, R.; Newton, L.; Brown, R.S.; Parpia, A.S.; Cozma, I.; et al. Later school start times for supporting the education, health, and well-being of high school students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD009467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, L.; Sumar, N.; Barberio, A.M.; Trieu, K.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Tarasuk, V.; Webster, J.; Campbell, N.R.C. Population-level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 9, CD010166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.R.A.; Francis, D.P.; Hairi, N.N.; Othman, S.; Choo, W.Y. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD010321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno Tablante, E.; Pachón, H.; Guetterman, H.M.; Finkelstein, J.L. Fortification of wheat and maize flour with folic acid for population health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD012150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, C.; O’Mara-Eves, A.; Porter, J.; Coleman, T.; Perlen, S.M.; Thomas, J.; McKenzie, J.E. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD001055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coren, E.; Hossain, R.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Bakker, B. Interventions for promoting reintegration and reducing harmful behaviour and lifestyles in street-connected children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD009823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Mahmood, S.B.; Moin, A.; Kumar, R.; Mukhtar, K.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Food fortification with multiple micronutrients: Impact on health outcomes in general population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 12, CD011400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Gwirtz, J.A.; Pasricha, S.R. Fortification of maize flour with iron for controlling anaemia and iron deficiency in populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD010187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husk, K.; Lovell, R.; Cooper, C.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Garside, R. Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: A review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, CD010351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, G.; Sheehan, Y.; Badcock, N.A.; Francis, D.A.; Wang, H.C.; Kohnen, S.; Banales, E.; Anandakumar, T.; Marinus, E.; Castles, A. Phonics training for English-speaking poor readers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD009115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.H.; Schoonees, A.; Sriram, U.; Faure, M.; Seguin-Fowler, R.A. Caregiver involvement in interventions for improving children’s dietary intake and physical activity behaviors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD012547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosdøl, A.; Lidal, I.B.; Straumann, G.H.; Vist, G.E. Targeted mass media interventions promoting healthy behaviours to reduce risk of non-communicable diseases in adult, ethnic minorities. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD011683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Mithra, P.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Kumar, N.; De-Regil, L.M.; Nair, N.S.; Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Solon, J.A. Fortification of rice with vitamins and minerals for addressing micronutrient malnutrition. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD009902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, J.; Duench, S.; Trawin, J.; Dewidar, O.; Pardo Pardo, J.; Simeon, R.; DesMeules, M.; Gagnon, D.; Hatcher Roberts, J.; Hossain, A.; et al. Behavioural interventions delivered through interactive social media for health behaviour change, health outcomes, and health equity in the adult population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, CD012932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.; Sachdev, H.S.; Gera, T.; De-Regil, L.M.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Fortification of staple foods with zinc for improving zinc status and other health outcomes in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 6, CD010697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Philipsborn, P.; Stratil, J.M.; Burns, J.; Busert, L.K.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Polus, S.; Holzapfel, C.; Hauner, H.; Rehfuess, E. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and their effects on health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD012292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Redmore, J.; Watkins, S.H.; Kipping, R.; White, J.; Chittleborough, C.; Langford, R.; Er, V.; Lingam, R.; et al. Individual-, family-, and school-level interventions targeting multiple risk behaviours in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD009927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C.; Gibson, M.; Sowden, A.; Wright, K.; Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: Evidence from systematic reviews. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2010, 64, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karran, E.L.; Cashin, A.G.; Barker, T.; Boyd, M.A.; Chiarotto, A.; Dewidar, O.; Mohabir, V.; Petkovic, J.; Sharma, S.; Tejani, S.; et al. Using PROGRESS-plus to identify current approaches to the collection and reporting of equity-relevant data: A scoping review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 163, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, L.; Smith, E.R.; Barlow, J.; Livingstone, N.; Herath, N.; Wei, Y.; Spreckelsen, T.F.; Macdonald, G. Video feedback for parental sensitivity and attachment security in children under five years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 11, CD012348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revenson, T.A.; Zoccola, P.M. New Instructions to Authors Emphasize Open Science, Transparency, Full Reporting of Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample, and Avoidance of Piecemeal Publication. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, Z.; Willis, A.; Salisu-Olatunji, S.O.; Jeffers, S.; Khunti, K.; Routen, A. Reporting and representation of underserved groups in intervention studies for patients with multiple long-term conditions: A systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2024, 117, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retzer, A.; Jolly, K.; Calvert, M.; Adab, P.; Campbell, N.; Varney, J. Methodology Generation for Core Outcome Data Sets in Population Health Research. Available online: https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR135211 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Petticrew, M.; Wilson, P.; Wright, K.; Song, F. Quality of Cochrane reviews. Quality of Cochrane reviews is better than that of non-Cochrane reviews. BMJ 2002, 324, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Koletsi, D.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Madigan, C.; Pandis, N.; Loef, M.; Walach, H.; Sauer, S.; Kleijnen, J.; Seehra, J.; et al. Most healthcare interventions tested in Cochrane Reviews are not effective according to high quality evidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 148, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dewidar, O.; Rizvi, A.; Huang, J.; Desai, P.; Doyle, R.; Ghogomu, E.; Rader, T.; Nicholls, S.G.; Antequera, A.; et al. A scoping review establishes need for consensus guidance on reporting health equity in observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 160, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.; Lawson, D.O.; Young, T.; Dewidar, O.; Nicholls, S.; Akl, E.A.; Little, J.; Magwood, O.; Shamseer, L.; Ghogomu, E.; et al. Guidance relevant to the reporting of health equity in observational research: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuagbaw, L.; Aves, T.; Shea, B.; Jull, J.; Welch, V.; Taljaard, M.; Yoganathan, M.; Greer-Smith, R.; Wells, G.; Tugwell, P. Considerations and guidance in designing equity-relevant clinical trials. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, R.; Galizia, I.; Tanaka, S.; Sheffel, A.; Buse, K.; Hawkes, S. The gender and geography of publishing: A review of sex/gender reporting and author representation in leading general medical and global health journals. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauh, T.J.; Read, J.G.; Scheitler, A.J. The Critical Role of Racial/Ethnic Data Disaggregation for Health Equity. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2021, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, L.; Carroll, C. Implications of research that excludes under-served populations. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). Levelling up the United Kingdom; DLUHC: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Strategic Mapping of Institutional Frameworks and Their Approach to Equity; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo, K.B.; Wang, Y.C.; Harris, A.; Auerbach, J.; Koo, D.; O’Carroll, P. Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action for Public Health to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition—July 2023; UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. European Regional Obesity Report 2022; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics Childbearing for Women Born in Different Years, England and Wales: 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/childbearingforwomenbornindifferentyearsenglandandwales/2020 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Retzer, A.; Adab, P.; Calvert, M.; Campbell, N.; Varney, J.; Fisher, P.; Arhin-Tenkorang, D.; Merriman, J.; Harris, I.; Khatsuria, F.; et al. Core outcome set development in population health: Potential opportunities and methodological guidance. BMJ Public Health, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.K.; Balogun, O.O.; Ota, E.; Takahashi, K.; Mori, R. Supplementation with multiple micronutrients for breastfeeding women for improving outcomes for the mother and baby. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD010647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.J.; Taylor, F.; Martin, N.; Gottlieb, S.; Taylor, R.S.; Ebrahim, S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12, CD009217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akl, E.A.; Kairouz, V.F.; Sackett, K.M.; Erdley, W.S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Fiander, M.; Gabriel, C.; Schünemann, H. Educational games for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 1, CD006411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khudairy, L.; Flowers, N.; Wheelhouse, R.; Ghannam, O.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S.; Rees, K. Vitamin C supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD011114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khudairy, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Mead, E.; Johnson, R.E.; Fraser, H.; Olajide, J.; Murphy, M.; Velho, R.M.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD012691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaouat, S.; Reddy, V.K.; Räsänen, K.; Khan, S.; Lumens, M. Educational interventions for preventing lead poisoning in workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD013097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andras, A.; Ferket, B. Screening for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 4, CD010835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikpo, D.; Edet, E.S.; Chibuzor, M.T.; Odey, F.; Caldwell, D.M. Educational interventions for improving primary caregiver complementary feeding practices for children aged 24 months and under. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD011768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Camosso-Stefinovic, J.; Gillies, C.; Shaw, E.J.; Cheater, F.; Flottorp, S.; Robertson, N.; Wensing, M.; Fiander, M.; Eccles, M.P.; et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD005470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, M.M.; Strzeszynski, L.; Topor-Madry, R. Mass media interventions for smoking cessation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD004704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, O.O.; da Silva Lopes, K.; Ota, E.; Takemoto, Y.; Rumbold, A.; Takegata, M.; Mori, R. Vitamin supplementation for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, CD004073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Tu, X.; Wei, Q. Water for preventing urinary stones. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD004292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, J.; Bergman, H.; Kornør, H.; Wei, Y.; Bennett, C. Group-based parent training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in young children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD003680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, H.; Henschke, N.; Hungerford, D.; Pitan, F.; Ndwandwe, D.; Cunliffe, N.; Soares-Weiser, K. Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: Vaccines in use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD008521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergwall, S.; Johansson, A.; Sonestedt, E.; Acosta, S. High versus low-added sugar consumption for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 1, CD013320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G.; Gluud, L.L.; Nikolova, D.; Whitfield, K.; Krstic, G.; Wetterslev, J.; Gluud, C. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of cancer in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD007469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G.; Gluud, L.L.; Nikolova, D.; Whitfield, K.; Wetterslev, J.; Simonetti, R.G.; Bjelakovic, M.; Gluud, C. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 1, CD007470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buppasiri, P.; Lumbiganon, P.; Thinkhamrop, J.; Ngamjarus, C.; Laopaiboon, M.; Medley, N. Calcium supplementation (other than for preventing or treating hypertension) for improving pregnancy and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD007079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Movsisyan, A.; Stratil, J.M.; Biallas, R.L.; Coenen, M.; Emmert-Fees, K.M.F.; Geffert, K.; Hoffmann, S.; Horstick, O.; Laxy, M.; et al. International travel-related control measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD013717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, K.; Lancaster, T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD003440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carberry, A.E.; Gordon, A.; Bond, D.M.; Hyett, J.; Raynes-Greenow, C.H.; Jeffery, H.E. Customised versus population-based growth charts as a screening tool for detecting small for gestational age infants in low-risk pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD008549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, B.; Keats, E.C.; Bhutta, Z.A. Zinc supplementation for improving pregnancy and infant outcome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD000230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson-Chahhoud, K.; Ameer, F.; Sayehmiri, K.; Hnin, K.; van Agteren, J.E.M.; Sayehmiri, F.; Brinn, M.P.; Esterman, A.J.; Chang, A.B.; Smith, B.J. Mass media interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD001006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson-Chahhoud, K.V.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Sharrad, K.J.; Kopsaftis, Z.; Brinn, M.P.; To-A-Nan, R.; Bond, C.M. Community pharmacy personnel interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD003698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, S.; Ngo, H.T.T.; Liira, J.; Liira, H. Education and training for preventing sharps injuries and splash exposures in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 4, CD012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clar, C.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Loveman, E.; Kelly, S.A.M.; Hartley, L.; Flowers, N.; Germanò, R.; Frost, G.; Rees, K. Low glycaemic index diets for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD004467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.L.; Evans, J.R.; Smeeth, L. Community screening for visual impairment in older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD001054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.L.; Loveman, E.; O’Malley, C.; Azevedo, L.B.; Mead, E.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Ells, L.J.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Rees, K. Diet, physical activity, and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in preschool children up to the age of 6 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, CD012105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepinsek, M.A.; Taylor, E.A.; Michener, K.; Stewart, F. Interventions for preventing mastitis after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD007239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppo, A.; Galanti, M.R.; Giordano, L.; Buscemi, D.; Bremberg, S.; Faggiano, F. School policies for preventing smoking among young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, CD009990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.J.; Barrett, H.L.; Price, S.A.; Callaway, L.K.; Dekker Nitert, M. Probiotics for preventing gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 4, CD009951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Rayco-Solon, P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD007950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Noguera, M.F.; Calvache, J.A.; Bonfill Cosp, X.; Kotanidou, E.P.; Galli-Tsinopoulou, A. Supplementation with long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) to breastfeeding mothers for improving child growth and development. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD007901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demicheli, V.; Barale, A.; Rivetti, A. Vaccines for women for preventing neonatal tetanus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, V.; Jefferson, T.; Di Pietrantonj, C.; Ferroni, E.; Thorning, S.; Thomas, R.E.; Rivetti, A. Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD004876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, V.; Jefferson, T.; Ferroni, E.; Rivetti, A.; Di Pietrantonj, C. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD001269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyakova, M.; Shantikumar, S.; Colquitt, J.L.; Drew, C.M.; Sime, M.; MacIver, J.; Wright, N.; Clarke, A.; Rees, K. Systematic versus opportunistic risk assessment for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD010411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbert, J.O.; Elrashidi, M.Y.; Stead, L.F. Interventions for smokeless tobacco use cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 10, CD004306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Lawrenson, J.G. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD000253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, F.; Minozzi, S.; Versino, E.; Buscemi, D. Universal school-based prevention for illicit drug use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12, CD003020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanshawe, T.R.; Halliwell, W.; Lindson, N.; Aveyard, P.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD003289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faseru, B.; Richter, K.P.; Scheuermann, T.S.; Park, E.W. Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD002928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellmeth, G.L.T.; Heffernan, C.; Nurse, J.; Habibula, S.; Sethi, D. Educational and skills-based interventions for preventing relationship and dating violence in adolescents and young adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD004534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gaxiola, A.; De-Regil, L. Intermittent iron supplementation for reducing anaemia and its associated impairments in adolescent and adult menstruating women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD009218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Allara, E.; Bo, A.; Gasparrini, A.; Faggiano, F. Media campaigns for the prevention of illicit drug use in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD009287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiander, M.; McGowan, J.; Grad, R.; Pluye, P.; Hannes, K.; Labrecque, M.; Roberts, N.W.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Welch, V.; Tugwell, P. Interventions to increase the use of electronic health information by healthcare practitioners to improve clinical practice and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3, CD004749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, T.; Malavolti, M.; Borrelli, F.; Izzo, A.A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Horneber, M.; Vinceti, M. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 3, CD005004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodgren, G.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions to change the behaviour of health professionals and the organisation of care to promote weight reduction in children and adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD000984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodgren, G.; O’Brien, M.A.; Parmelli, E.; Grimshaw, J.M. Local opinion leaders: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD000125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsetlund, L.; O’Brien, M.A.; Forsén, L.; Mwai, L.; Reinar, L.M.; Okwen, M.P.; Horsley, T.; Rose, C.J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD003030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Richards, J.; Thorogood, M.; Hillsdon, M. Remote and web 2.0 interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9, CD010395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, D.R.; Moreira, M.T.; Almeida Santimano, N.M.L.; Smith, L.A. Social norms information for alcohol misuse in university and college students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD006748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.; Callinan, J.E.; McHugh, J.; van Baarsel, S.; Clarke, A.; Doherty, K.; Kelleher, C. Legislative smoking bans for reducing harms from secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD005992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, K.; McHugh, J.; Callinan, J.E.; Kelleher, C. Impact of institutional smoking bans on reducing harms and secondhand smoke exposure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, CD011856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.M.Z.; Andriolo, B.N.G.; Torloni, M.R.; Soares, B.G.O.; de Oliveira Gomes, J.; Andriolo, R.B.; Canteiro Cruz, E. Vaccines for preventing herpes zoster in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 11, CD008858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartlehner, G.; Thaler, K.; Chapman, A.; Kaminski-Hartenthaler, A.; Berzaczy, D.; Van Noord, M.G.; Helbich, T.H. Mammography in combination with breast ultrasonography versus mammography for breast cancer screening in women at average risk. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD009632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, A.; Zomahoun, H.T.; Carmichael, P.-H.; Uwizeye, C.B.; Légaré, F.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Auguste, D.U.; Massougbodji, J. Printed educational materials: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD004398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.J.; Maria, A.R.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Villanueva, G.; Fønhus, M.S.; Glenton, C.; Lewin, S.; Henschke, N.; Buckley, B.S.; Mehl, G.L.; et al. Mobile technologies to support healthcare provider to healthcare provider communication and management of care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD012927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, A.J.; Reid, H.; Thomas, E.E.; Nunan, D.; Foster, C. Exercise prior to influenza vaccination for limiting influenza incidence and its related complications in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD011857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafdi, M.; Hoevenaar-Blom, M.P.; Richard, E. Multi-domain interventions for the prevention of dementia and cognitive decline. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD013572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.; O’Doherty, L.; Gilchrist, G.; Tirado-Muñoz, J.; Taft, A.; Chondros, P.; Feder, G.; Tan, M.; Hegarty, K. Psychological therapies for women who experience intimate partner violence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD013017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, K.B.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Webster, A.C.; Yap, C.M.Y.; Payne, B.A.; Ota, E.; De-Regil, L.M. Iodine supplementation for women during the preconception, pregnancy and postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD011761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, L.; Flowers, N.; Holmes, J.; Clarke, A.; Stranges, S.; Hooper, L.; Rees, K. Green and black tea for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD009934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; Igbinedion, E.; Holmes, J.; Flowers, N.; Thorogood, M.; Clarke, A.; Stranges, S.; Hooper, L.; Rees, K. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD009874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; Dyakova, M.; Holmes, J.; Clarke, A.; Lee, M.S.; Ernst, E.; Rees, K. Yoga for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD010072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, L.; Clar, C.; Ghannam, O.; Flowers, N.; Stranges, S.; Rees, K. Vitamin K for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD011148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; May, M.D.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Rees, K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD011472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Chepkin, S.C.; Ye, W.; Bullen, C.; Lancaster, T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lindson, N.; Freeman, S.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Theodoulou, A.; Aveyard, P. Behavioural interventions for smoking cessation: An overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD013229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Theodoulou, A.; Farley, A.; Hajek, P.; Lycett, D.; Jones, L.L.; Kudlek, L.; Heath, L.; Hajizadeh, A.; Schenkels, M.; et al. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, CD006219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Lindson, N.; Butler, A.R.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Begh, R.; Theodoulou, A.; Notley, C.; Rigotti, N.A.; Turner, T.; et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, CD010216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefler, M.; Liberato, S.C.; Thomas, D.P. Incentives for preventing smoking in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD008645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H.; Chalker, E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 1, CD000980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H.; Louhiala, P. Vitamin C for preventing and treating pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD005532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, V.C.W.; Urquhart, D.M.; Kelsall, H.L.; Zamri, E.N.; Sim, M.R. Ergonomic interventions for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck among office workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD008570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, G.J.; Lawrie, T.A.; Atallah, Á.N.; Torloni, M.R. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, G.J.; Manyame, S.; Medley, N.; Williams, M.J. Calcium supplementation commencing before or early in pregnancy, for preventing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD011192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Adedire, O.; Copsey, B.J.; Boniface, G.J.; Sherrington, C.; Clemson, L.; Close, J.C.T.; Lamb, S.E. Multifactorial and multiple component interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD012221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, S.L.; Acharya, N.; Silver, A.; Sheni, R.; Yu, E.A.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Mehta, S. Effects of oral vitamin D supplementation on linear growth and other health outcomes among children under five years of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD012875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, S.H.; Ho, J.J.; Jahanfar, S.; Angolkar, M. Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD007202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Brown, J.; Norris, E.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Hayes, E.; Lindson, N. Mindfulness for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 4, CD013696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson Vann, J.C.; Jacobson, R.M.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Asafu-Adjei, J.K.; Szilagyi, P.G. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD003941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanfar, S.; Jaafar, S.H. Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD006965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasani, B.; Simmer, K.; Patole, S.K.; Rao, S.C. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in infants born at term. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD000376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.; Jawad, I.; Alwan, N.A. Interventions using social networking sites to promote contraception in women of reproductive age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yuan, B.; Huang, F.; Lu, Y.; Garner, P.; Meng, Q. Strategies for expanding health insurance coverage in vulnerable populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD008194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, N.; Hooker, L.; Reisenhofer, S.; Di Tanna, G.L.; García-Moreno, C. Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, CD012423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsch-Völk, M.; Barrett, B.; Kiefer, D.; Bauer, R.; Ardjomand-Woelkart, K.; Linde, K. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD000530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Ryan, R.; Walsh, L.; Horey, D.; Leask, J.; Robinson, P.; Hill, S. Face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD010038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, E.C.; Haider, B.A.; Tam, E.; Bhutta, Z.A. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD004905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, M.M.; Phillips, R.; Brown, S.J.; Cro, S.; Cornelius, V.; Carlsen, K.C.; Lødrup Skjerven, H.O.; Rehbinder, E.M.; Lowe, A.J.; Dissanayake, E.; et al. Skin care interventions in infants for preventing eczema and food allergy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, CD013534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.A.M.; Hartley, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Jones, H.M.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Clar, C.; Germanò, R.; Lunn, H.R.; Frost, G.; et al. Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD005051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, D.; Mulvaney, C.A.; Ye, L.; Stevens, T.; Mytton, J.A.; Stewart-Brown, S. Parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 3, CD006020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaratne, S.; Littlecott, H.; Sell, K.; Burns, J.; Rabe, J.E.; Stratil, J.M.; Litwin, T.; Kreutz, C.; Coenen, M.; Geffert, K.; et al. Measures implemented in the school setting to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 1, CD015029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogsbøll, L.T.; Jørgensen, K.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C. General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD009009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehnl, A.; Seubert, C.; Rehfuess, E.; von Elm, E.; Nowak, D.; Glaser, J. Human resource management training of supervisors for improving health and well-being of employees. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD010905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Helmreich, I.; Chmitorz, A.; König, J.; Binder, H.; Wessa, M.; Lieb, K. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD012527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, A.T.; Dalsbø, T.K.; Luong Thanh, B.Y.; Agarwal, A.; Durand-Moreau, Q.V.; Kirkehei, I. Computer-based versus in-person interventions for preventing and reducing stress in workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD011899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, R.; Yazdizadeh, B.; Davari, M.; Nouhi, M.; Kelishadi, R. Newborn screening for galactosaemia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 6, CD012272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Salam, R.A.; Haider, B.A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Folic acid supplementation during pregnancy for maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 3, CD006896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrenson, J.G.; Evans, J.R. Omega 3 fatty acids for preventing or slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD010015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E.; Fisher, E.; Eccleston, C.; Palermo, T.M. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD009660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindson, N.; Klemperer, E.; Hong, B.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Aveyard, P. Smoking reduction interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD013183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindson-Hawley, N.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Begh, R.; Farley, A.; Lancaster, T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, CD005231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissiman, E.; Bhasale, A.L.; Cohen, M. Garlic for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD006206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.Y.; Zhong, B.L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for family carers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 8, CD012791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, N.; Macdonald, G.; Carr, N. Restorative justice conferencing for reducing recidivism in young offenders (aged 7 to 21). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, CD008898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone-Banks, J.; Norris, E.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; West, R.; Jarvis, M.; Chubb, E.; Hajek, P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD003999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone-Banks, J.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Print-based self-help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD001118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.M.; Grey, T.W.; Chen, M.; Denison, J.; Stuart, G. Behavioral interventions for improving contraceptive use among women living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD010243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.M.; Steiner, M.; Grimes, D.A.; Hilgenberg, D.; Schulz, K.F. Strategies for communicating contraceptive effectiveness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD006964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.M.; Grey, T.W.; Hiller, J.E.; Chen, M. Education for contraceptive use by women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD001863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.M.; Bernholc, A.; Chen, M.; Tolley, E.E. School-based interventions for improving contraceptive use in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 6, CD012249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.M.; Grey, T.W.; Tolley, E.E.; Chen, M. Brief educational strategies for improving contraception use in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, CD012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveman, E.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Johnson, R.E.; Robertson, W.; Colquitt, J.L.; Mead, E.L.; Ells, L.J.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Rees, K. Parent-only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong Thanh, B.Y.; Laopaiboon, M.; Koh, D.; Sakunkoo, P.; Moe, H. Behavioural interventions to promote workers’ use of respiratory protective equipment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD010157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Sánchez, L.; Clark, P.; Winzenberg, T.M.; Tugwell, P.; Correa-Burrows, P.; Costello, R. Calcium and vitamin D for increasing bone mineral density in premenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD012664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrides, M.; Crosby, D.D.; Shepherd, E.; Crowther, C.A. Magnesium supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 4, CD000937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.C.C.; Worthington, H.; Walsh, T.; Chong, L.-Y. Fluoride gels for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD002280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.C.C.; Chong, L.-Y.; Worthington, H.V.; Walsh, T. Fluoride mouthrinses for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD002284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Germanò, R.; Hartley, L.; Adler, A.J.; Rees, K. Nut consumption for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD011583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziak, W.; Jawad, M.; Jawad, S.; Ward, K.D.; Eissenberg, T.; Asfar, T. Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD005549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeill, A.; Gravely, S.; Hitchman, S.C.; Bauld, L.; Hammond, D.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Tobacco packaging design for reducing tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD011244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, E.; Brown, T.; Rees, K.; Azevedo, L.B.; Whittaker, V.; Jones, D.; Olajide, J.; Mainardi, G.M.; Corpeleijn, E.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD012651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medley, N.; Vogel, J.P.; Care, A.; Alfirevic, Z. Interventions during pregnancy to prevent preterm birth: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD012505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, P.; Gomersall, J.C.; Gould, J.F.; Shepherd, E.; Olsen, S.F.; Makrides, M. Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD003402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.J.; Murray, L.; Beckmann, M.M.; Kent, T.; Macfarlane, B. Dietary supplements for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 10, CD009104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischke, C.; Verbeek, J.H.; Job, J.; Morata, T.C.; Alvesalo-Kuusi, A.; Neuvonen, K.; Clarke, S.; Pedlow, R.I. Occupational safety and health enforcement tools for preventing occupational diseases and injuries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD010183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Guevara, C.; Buitrago-Garcia, D.; Felix, M.L.; Guerra, C.V.; Hidalgo, R.; Martinez-Zapata, M.J.; Simancas-Racines, D. Vaccines for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 12, CD002190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motuhifonua, S.K.; Lin, L.; Alsweiler, J.; Crawford, T.J.; Crowther, C.A. Antenatal dietary supplementation with myo-inositol for preventing gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2, CD011507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktabhant, B.; Lawrie, T.A.; Lumbiganon, P.; Laopaiboon, M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD007145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naude, C.E.; Visser, M.E.; Nguyen, K.A.; Durao, S.; Schoonees, A. Effects of total fat intake on bodyweight in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD012960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndikom, C.M.; Fawole, B.; Ilesanmi, R.E. Extra fluids for breastfeeding mothers for increasing milk production. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD008758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noone, C.; McSharry, J.; Smalle, M.; Burns, A.; Dwan, K.; Devane, D.; Morrissey, E.C. Video calls for reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD013632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notley, C.; Gentry, S.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Bauld, L.; Perera, R.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD004307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, C.; Hawton, K.; Lloyd, K.; Price, S.F.; Dennis, M.; John, A. Means restriction for the prevention of suicide on roads. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD013738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, C.; Wood, S.; Hawton, K.; Kandalama, U.; Glendenning, A.C.; Dennis, M.; Price, S.F.; Lloyd, K.; John, A. Means restriction for the prevention of suicide by jumping. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD013543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.G.; Gordon, M.; Banks, S.S.C.; Thomas, M.R.; Akobeng, A.K. Probiotics to prevent infantile colic. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, D.A.; Sinn, J.K.H. Prebiotics in infants for prevention of allergy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 3, CD006474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, D.A.; Sinn, J.K.H.; Jones, L.J. Infant formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergic disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD003664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachito, D.V.; Eckeli, A.L.; Desouky, A.S.; Corbett, M.A.; Partonen, T.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Riera, R. Workplace lighting for improving alertness and mood in daytime workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD012243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.; Trak-Fellermeier, M.A.; Martinez, R.X.; Lopez-Perez, L.; Lips, P.; Salisi, J.A.; John, J.C.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Regimens of vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD013446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja, T.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Colomer, N.; Castañon, C.; Leniz Martelli, J. Manually-generated reminders delivered on paper: Effects on professional practice and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 12, CD001174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Dowswell, T. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD004736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Rosas, J.P.; De-Regil, L.M.; Gomez Malave, H.; Flores-Urrutia, M.C.; Dowswell, T. Intermittent oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 10, CD009997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, N.; Balakrishna, Y.; Durao, S. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD005266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosino, A.; Turpin-Petrosino, C.; Hollis-Peel, M.E.; Lavenberg, J.G. ‘Scared Straight’ and other juvenile awareness programs for preventing juvenile delinquency. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD002796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Hartley, L.; Day, C.; Flowers, N.; Clarke, A.; Stranges, S. Selenium supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 1, CD009671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, K.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Takeda, A.; Stranges, S. Vegan dietary pattern for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2, CD013501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, S.; Perrier, L.; Goldman, J.; Freeth, D.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 3, CD002213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelone, F.; Harrison, R.; Goldman, J.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Hillsdon, M.; Thorogood, M.; Foster, C. Face-to-face interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9, CD010392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Thorogood, M.; Hillsdon, M.; Foster, C. Face-to-face versus remote and web 2.0 interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9, CD010393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, C.; Ramsay, J.; Sadowski, L.; Davidson, L.L.; Dunne, D.; Eldridge, S.; Hegarty, K.; Taft, A.; Feder, G. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3, CD005043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, C.; Vigurs, C.; Cameron, J.; Yeo, L. A realist review of which advocacy interventions work for which abused women under what circumstances. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD013135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.; Yeoh, S.E.; Kolbach, D.N. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing venous insufficiency in a standing worker population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 10, CD006345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, A.; Ota, E.; Hori, H.; Miyazaki, C.; Crowther, C.A. Vitamin E supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD004069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, A.; Ota, E.; Nagata, C.; Shahrook, S.; Crowther, C.A. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD004072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjes, A.W.S.; Denton, D.A.; Di Nisio, M.; Chong, L.Y.; Abraham, R.P.; Al-Assaf, A.S.; Anderson, J.L.; Malik, M.A.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Martínez, G.; et al. Vitamin and mineral supplementation for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in mid and late life. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD011906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeterdal, I.; Lewin, S.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Glenton, C.; Munabi-Babigumira, S. Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, R.; Zuberi, N.F.; Bhutta, Z.A. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD000179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandall, J.; Soltani, H.; Gates, S.; Shennan, A.; Devane, D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD004667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangkomkamhang, U.S.; Lumbiganon, P.; Laopaiboon, M. Hepatitis B vaccination during pregnancy for preventing infant infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD007879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santesso, N.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Brignardello-Petersen, R. Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in older people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, CD001255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauni, R.; Verbeek, J.H.; Uitti, J.; Jauhiainen, M.; Kreiss, K.; Sigsgaard, T. Remediating buildings damaged by dampness and mould for preventing or reducing respiratory tract symptoms, infections and asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD007897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, F.G.; Mahmud, N.; Reneman, M.F.; Fassier, J.B.; Jungbauer, F.H.W. Pre-employment examinations for preventing injury, disease and sick leave in workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD008881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, T.; Sinn, J.K.H.; Osborn, D.A. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in infancy for the prevention of allergy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, CD010112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmucker, C.; Eisele-Metzger, A.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Lehane, C.; Kuellenberg de Gaudry, D.; Lohner, S.; Schwingshackl, L. Effects of a gluten-reduced or gluten-free diet for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 2, CD013556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.M.; Clark, J.; Julien, B.; Islam, F.; Roos, K.; Grimwood, K.; Little, P.; Del Mar, C.B. Probiotics for preventing acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD012941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.T.; Verbeek, J.H.; Ijaz, S.; Hermans, V.; Pedisic, Z. Workplace interventions for reducing sitting at work. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD010912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltan, F.; Cristofalo, D.; Marshall, D.; Purgato, M.; Taddese, H.; Vanderbloemen, L.; Barbui, C.; Uphoff, E. Community-based interventions for improving mental health in refugee children and adolescents in high-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD013657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staley, H.; Shiraz, A.; Shreeve, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.L.; Gajjar, K. Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD002834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, L.F.; Carroll, A.J.; Lancaster, T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD001007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.L.; Abrams, S.A.; Osborn, D.A. Vitamin D supplementation for term breastfed infants to prevent vitamin D deficiency and improve bone health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD013046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattan-Birch, H.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Kock, L.; Simonavicius, E.; Brose, L.; Jackson, S.; Shahab, L.; Brown, J. Heated tobacco products for smoking cessation and reducing smoking prevalence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 1, CD013790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.M.J.; Lindson, N.; Farley, A.; Leinberger-Jabari, A.; Sawyer, K.; te Water Naudé, R.; Theodoulou, A.; King, N.; Burke, C.; Aveyard, P. Smoking cessation for improving mental health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD013522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; McLellan, J.; Perera, R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD001293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Baker, P.R.; Thomas, B.C.; Lorenzetti, D.L. Family-based programmes for preventing smoking by children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD004493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Lorenzetti, D.L. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD005188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieu, J.; McPhee, A.J.; Crowther, C.A.; Middleton, P.; Shepherd, E. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus based on different risk profiles and settings for improving maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD007222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikka, C.; Verbeek, J.H.; Kateman, E.; Morata, T.C.; Dreschler, W.A.; Ferrite, S. Interventions to prevent occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD006396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uphoff, E.; Robertson, L.; Cabieses, B.; Villalón, F.J.; Purgato, M.; Churchill, R.; Barbui, C. An overview of systematic reviews on mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment of common mental disorders for refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD013458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ussher, M.H.; Faulkner, G.E.J.; Angus, K.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Taylor, A.H. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD002295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, F.A.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Reda, A.A.; Winkens, B.; Evers, S.; Kotz, D.; van Schayck, O.C.P. Healthcare financing systems for increasing the use of tobacco dependence treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD004305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaona, A.; Banzi, R.; Kwag, K.H.; Rigon, G.; Cereda, D.; Pecoraro, V.; Tramacere, I.; Moja, L. E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD011736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgara, R.; Phillips, A.; Lewis, L.K.; Baldock, K.; Wolfenden, L.; Ferguson, T.; Richardson, M.; Okely, A.; Beets, M.; Maher, C. Interventions in outside-school hours childcare settings for promoting physical activity amongst schoolchildren aged 4 to 12 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD013380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T.; Worthington, H.V.; Glenny, A.M.; Marinho, V.C.C.; Jeroncic, A. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD007868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; Eggins, E.; Hine, L.; Mathews, B.; Kenny, M.C.; Howard, S.; Ayling, N.; Dallaston, E.; Pink, E.; Vagenas, D. Child protection training for professionals to improve reporting of child abuse and neglect. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 7, CD011775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Rodgers, A.; Gu, Y.; Dobson, R. Mobile phone text messaging and app-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD006611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Goldman, S.; Stacey, F.G.; Grady, A.; Kingsland, M.; Williams, C.M.; Wiggers, J.; Milat, A.; Rissel, C.; Bauman, A.; et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies or practices targeting tobacco, alcohol, diet, physical activity and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD012439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Barnes, C.; Jones, J.; Finch, M.; Wyse, R.J.; Kingsland, M.; Tzelepis, F.; Grady, A.; Hodder, R.K.; Booth, D.; et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD011779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaacob, M.; Worthington, H.V.; Deacon, S.A.; Deery, C.; Walmsley, A.D.; Robinson, P.G.; Glenny, A.M. Powered versus manual toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD002281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonemoto, N.; Nagai, S.; Mori, R. Schedules for home visits in the early postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 7, CD009326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.; Angevaren, M.; Rusted, J.; Tabet, N. Aerobic exercise to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD005381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; El-Gibaly, O.M.H.; EL-Gazzar, A.F.E.S.; Al-Attar, G.S.T. Mobile clinics for women’s and children’s health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD009677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, L.H.; Kagina, B.M.; Ndze, V.N.; Hussey, G.D.; Wiysonge, C.S. Improving vaccination uptake among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD011895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammenwerth, E.; Neyer, S.; Hörbst, A.; Mueller, G.; Siebert, U.; Schnell-Inderst, P. Adult patient access to electronic health records. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2, CD012707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.M.; Adeney, K.L.; Shinn, C.; Safranek, S.; Buckner-Brown, J.; Krause, L.K. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD009905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Kumbargere Nagraj, S.; Khattri, S.; Ismail, N.M.; Eachempati, P. School dental screening programmes for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 7, CD012595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.R.A.; Francis, D.P.; Soares, J.; Weightman, A.L.; Foster, C. Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD008366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Smailagic, N.; Huband, N.; Roloff, V.; Bennett, C. Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD002020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Rönsch, H.; Elsner, P.; Dittmar, D.; Bennett, C.; Schuttelaar, M.L.A.; Lukács, J.; John, S.M.; Williams, H.C. Interventions for preventing occupational irritant hand dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, CD004414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrie, F.R.P.; Bearn, D.R.; Innes, N.P.T.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z. Interventions for the cessation of non-nutritive sucking habits in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3, CD008694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Boogaard, H.; Polus, S.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Rohwer, A.C.; van Erp, A.M.; Turley, R.; Rehfuess, E. Interventions to reduce ambient particulate matter air pollution and their effect on health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 5, CD010919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byber, K.; Radtke, T.; Norbäck, D.; Hitzke, C.; Imo, D.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Puhan, M.A.; Dressel, H.; Mutsch, M. Humidification of indoor air for preventing or reducing dryness symptoms or upper respiratory infections in educational settings and at the workplace. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 12, CD012219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catling, C.J.; Medley, N.; Foureur, M.; Ryan, C.; Leap, N.; Teate, A.; Homer, C.S.E. Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD007622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithongwongwatthana, S.; Yamasmit, W.; Limpongsanurak, S.; Lumbiganon, P.; Tolosa, J.E. Pneumococcal vaccination during pregnancy for preventing infant infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD004903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastin, S.; Gardiner, P.A.; Harvey, J.A.; Leask, C.F.; Jerez-Roig, J.; Rosenberg, D.; Ashe, M.C.; Helbostad, J.L.; Skelton, D.A. Interventions for reducing sedentary behaviour in community-dwelling older adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 6, CD012784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.; Opiyo, N.; Tavender, E.; Mortazhejri, S.; Rader, T.; Petkovic, J.; Yogasingam, S.; Taljaard, M.; Agarwal, S.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, CD005528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clar, C.; Oseni, Z.; Flowers, N.; Keshtkar-Jahromi, M.; Rees, K. Influenza vaccines for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 5, CD005050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.M.; O’Malley, L.A.; Elison, S.N.; Armstrong, R.; Burnside, G.; Adair, P.; Dugdill, L.; Pine, C. Primary school-based behavioural interventions for preventing caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 5, CD009378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, R.A.; King, S.E.; Marteau, T.M.; Prevost, A.T.; Bignardi, G.; Roberts, N.W.; Stubbs, B.; Hollands, G.J.; Jebb, S.A. Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD009315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desapriya, E.; Harjee, R.; Brubacher, J.; Chan, H.; Hewapathirane, D.S.; Subzwari, S.; Pike, I. Vision screening of older drivers for preventing road traffic injuries and fatalities. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD006252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.C.; Rothpletz-Puglia, P.; Dreker, M.R.; Iannotti, L.; Lutter, C.; Kaganda, J.; Rayco-Solon, P. Effectiveness of provision of animal-source foods for supporting optimal growth and development in children 6 to 59 months of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, CD012818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.G.K.; Naik, G.; Ahmed, H.; Elwyn, G.J.; Pickles, T.; Hood, K.; Playle, R. Personalised risk communication for informed decision making about taking screening tests. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, CD001865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejere, H.O.; Alhassan, M.B.; Rabiu, M. Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD003659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Els, C.; Jackson, T.D.; Milen, M.T.; Kunyk, D.; Wyatt, G.; Sowah, D.; Hagtvedt, R.; Deibert, D.; Straube, S. Random drug and alcohol testing for preventing injury in workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 12, CD012921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fanshawe, T.R.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Perera, R.; Lindson, N. Competitions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, CD013272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freak-Poli, R.L.A.; Cumpston, M.; Albarqouni, L.; Clemes, S.A.; Peeters, A. Workplace pedometer interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD009209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.J.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Di Nisio, M.; Karim, S.; Chong, L.Y.; March, E.; Martínez, G.; Vernooij, R.W.M. Computerised cognitive training for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in midlife. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.J.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Di Nisio, M.; Karim, S.; Chong, L.Y.; March, E.; Martínez, G.; Vernooij, R.W.M. Computerised cognitive training for 12 or more weeks for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in late life. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD012277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, M.; Thomson, H.; Banas, K.; Lutje, V.; McKee, M.J.; Martin, S.P.; Fenton, C.; Bambra, C.; Bond, L. Welfare-to-work interventions and their effects on the mental and physical health of lone parents and their children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD009820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillen, P.; Sinclair, M.; Kernohan, W.G.; Begley, C.M.; Luyben, A.G. Interventions for prevention of bullying in the workplace. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, CD009778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fraile, E.; Ballesteros, J.; Rueda, J.-R.; Santos-Zorrozúa, B.; Solà, I.; McCleery, J. Remotely delivered information, training and support for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD006440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyder, C.; Atherton, H.; Car, M.; Heneghan, C.J.; Car, J. Email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2, CD007979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, A.J.; Keogh, J.; Silva, V.; Scott, A.M. Exercise versus no exercise for the occurrence, severity, and duration of acute respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD010596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulani, A.; Sachdev, H.S. Zinc supplements for preventing otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD006639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrod, C.S.; Goss, C.W.; Stallones, L.; DiGuiseppi, C. Interventions for primary prevention of suicide in university and other post-secondary educational settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, CD009439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; Flowers, N.; Lee, M.S.; Ernst, E.; Rees, K. Tai chi for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 4, CD010366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; Lee, M.S.; Kwong, J.S.W.; Flowers, N.; Todkill, D.; Ernst, E.; Rees, K. Qigong for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD010390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, L.; Horey, D.; Romios, P.; Kis-Rigo, J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD009405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hult, M.; Lappalainen, K.; Saaranen, T.K.; Räsänen, K.; Vanroelen, C.; Burdorf, A. Health-improving interventions for obtaining employment in unemployed job seekers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1, CD013152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Worthington, H.V.; Walsh, T.; O’Malley, L.; Clarkson, J.E.; Macey, R.; Alam, R.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Glenny, A.M. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 6, CD010856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, D.; Kumar, A.; Carpenter, H.; Zijlstra, G.A.R.; Skelton, D.A.; Cook, J.R.; Stevens, Z.; Belcher, C.M.; Haworth, D.; Gawler, S.J.; et al. Exercise for reducing fear of falling in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD009848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, K.M.; Carr, R.; Donovan, T.; Gordon, M. Asthma education for school staff. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD012255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, T.; Maher, C.G.; Rieger, M.A.; Steinhilber, B. Work-break schedules for preventing musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders in healthy workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD012886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbiganon, P.; Martis, R.; Laopaiboon, M.; Festin, M.R.; Ho, J.J.; Hakimi, M. Antenatal breastfeeding education for increasing breastfeeding duration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD006425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, R.; Lethaby, A.; Irving, L.B.; Stone, C.; Byrnes, G.; Abramson, M.J.; Campbell, D. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD001991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Booth, J.N.; Laird, Y.; Sproule, J.; Reilly, J.J.; Saunders, D.H. Physical activity, diet and other behavioural interventions for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD009728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastellos, N.; Gunn, L.H.; Felix, L.M.; Car, J.; Majeed, A. Transtheoretical model stages of change for dietary and physical exercise modification in weight loss management for overweight and obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD008066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, C.A.; Smith, S.; Watson, M.C.; Parkin, J.; Coupland, C.; Miller, P.; Kendrick, D.; McClintock, H. Cycling infrastructure for reducing cycling injuries in cyclists. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD010415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Lockwood, C.; Stern, C.; McAneney, H.; Barker, T.H. Rinse-free hand wash for reducing absenteeism among preschool and school children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD012566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtagh, E.M.; Murphy, M.H.; Milton, K.; Roberts, N.W.; O’Gorman, C.S.M.; Foster, C. Interventions outside the workplace for reducing sedentary behaviour in adults under 60 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 7, CD012554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]