Exploring Male Body Image: A Scoping Review of Measurement Approaches and Mental Health Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prior Reviews of Body Image Measures

- The Body Dissatisfaction Scale of the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI BD);

- The Drive for Thinness subscale of the EDI;

- The Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ);

- The Shape and Weight Concern subscales of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE Q);

- The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS);

- The Contour Drawing Rating Scale (CDRS);

- The Body Image Ideals Questionnaire (BIQ);

- The Body Image Satisfaction Scale (BISS).

1.2. The Current Review

1.3. Research Questions

1.4. Scoping Review Purpose (PCC)

2. Methods

2.1. Research Framework

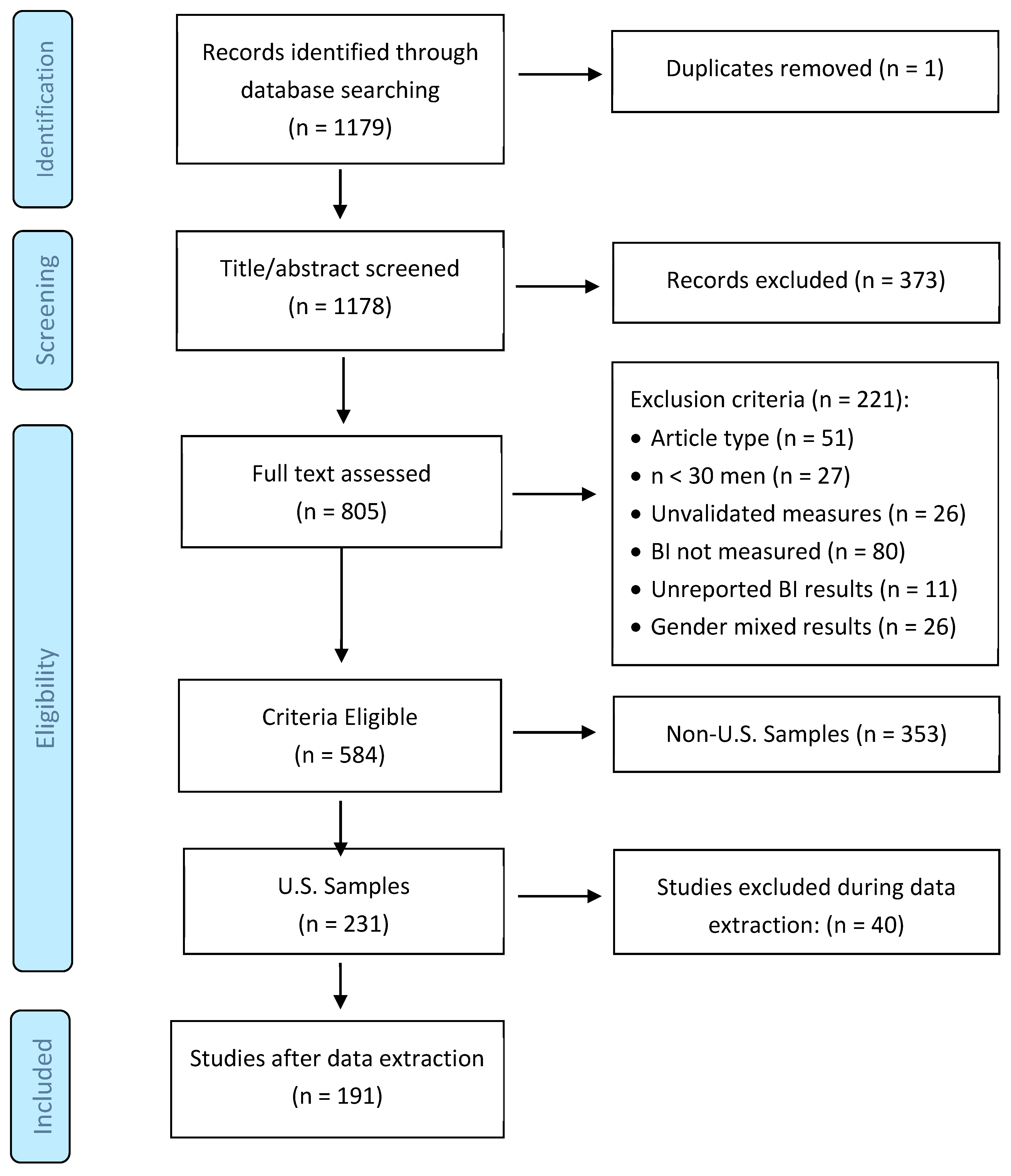

2.2. Identification and Selection of Studies

2.3. Screening Process

- Non-empirical, non-quantitative, or qualitative publications, or conference abstracts (n = 51);

- Sample size of fewer than 30 cisgender men (n = 27);

- Use of unvalidated body image measures (n = 26);

- Body image not assessed (n = 80);

- Results not disaggregated by gender (n = 26);

- Insufficient quantitative results for effect-size extraction (n = 11);

2.4. Classification of Measures

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Relative Popularity of Thinness-, Muscularity-, and Non-Specific Measures

3.3. Research on Mental-Health Outcomes and Body Image

3.3.1. Thinness-Oriented Body Image Measures

3.3.2. Muscularity-Oriented Measures of Body Image

3.3.3. Non-Specific Measures of Body Image

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Characteristics and Measure Utilization

4.2. Associations Between BI and Mental Health Outcomes

4.2.1. Depression

4.2.2. Anxiety

4.2.3. Self-Esteem

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, Z.J.; Rodriguez, P.; Wright, D.R.; Austin, S.B.; Long, M.W. Estimation of Eating Disorders Prevalence by Age and Associations With Mortality in a Simulated Nationally Representative US Cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcelus, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Wales, J.; Nielsen, S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blinder, B.J.; Cumella, E.J.; Sanathara, V.A. Psychiatric comorbidities of female inpatients with eating disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milos, G.; Spindler, A.; Hepp, U.; Schnyder, U. Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation: Links with psychiatric comorbidity in eating disorder subjects. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milos, G.F.; Spindler, A.M.; Buddeberg, C.; Crameri, A. Axes I and II comorbidity and treatment experiences in eating disorder subjects. Psychother. Psychosom. 2003, 72, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F. Body image: Past, present, and future. Body Image 2004, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M. Body image across the adult life span: Stability and change. Body Image 2004, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.D. What is body image? Behav. Res. Ther. 1994, 32, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P. Causes of eating disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, L.; Johnston, L.S.; Augustyniak, K. Prevention of eating disorders: Identification of predictor variables. Eat. Disord. J. Treat. Prev. 1999, 7, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Resnick, M.D.; Garwick, A.; Blum, R.W. Body dissatisfaction and unhealthy weight-control practices among adolescents with and without chronic illness: A population-based study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1995, 149, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, L.; Zeman, J. The Contribution of Emotion Regulation to Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating in Early Adolescent Girls. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.A.; Mond, J.; Eisenberg, M.; Ackard, D.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. The link between body dissatisfaction and self-esteem in adolescents: Similarities across gender, age, weight status, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.B.; Brownell, K.D.; Wilfley, D.E. Relationship of weight, body dissatisfaction, and self-esteem in African American and white female dieters. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1997, 22, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfield, G.S.; Moore, C.; Henderson, K.; Buchholz, A.; Obeid, N.; Flament, M.F. Body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, depression, and weight status in adolescents. J. Sch. Health 2010, 80, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederman, M.W.; Pryor, T.L. Body dissatisfaction, bulimia, and depression among women: The mediating role of drive for thinness. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2000, 27, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; Abhyankar, P.; Dimova, E.; Best, C. Associations between body dissatisfaction and self-reported anxiety and depression in otherwise healthy men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.M.; Ferraro, F.R. Body satisfaction in college women after brief exposure to magazine images. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2004, 98 Pt 1, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Henry, P.E. Women’s body images: The results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Sex Roles 1995, 33, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafini, B.A.; Pozzilli, P. Body weight and beauty: The changing face of the ideal female body weight. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbner’s Cultivation Theory in Media Communication. 2023. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/cultivation-theory.html (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Thompson, J.K. The (mis)measurement of body image: Ten strategies to improve assessment for applied and research purposes. Body Image 2004, 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, S. Promoting Positive Body Image in Males and Females: Contemporary Issues and Future Directions. Sex Roles 2010, 63, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, D.R.; Sasse, D.K. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. J. Am. Coll. Health 2000, 48, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Bergeron, D.; Schwartz, J.P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Male Body Attitudes Scale (MBAS). Body Image 2005, 2, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleaves, D.H.; Cepeda-Benito, A.; Williams, T.L.; Cororve, M.B.; Fernandez, M.d.C.; Vila, J. Body image preferences of self and others: A comparison of spanish and american male and female college students. Eat. Disord. 2000, 8, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.D.; Adler, N.E. Female and male perceptions of ideal body shapes: Distorted views among Caucasian college students. Psychol. Women Q. 1992, 16, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Greene, P.A. Gender differences in body weight perception and weight-loss strategies of college students. Women Health 1988, 14, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schooler, D.; Ward, L.M. Average Joes: Men’s relationships with media, real bodies, and sexuality. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2006, 7, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leit, R.A.; Pope, H.G.; Gray, J.J. Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: The evolution of playgirl centerfolds. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2001, 29, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, H.G.; Olivardia, R.; Gruber, A.; Borowiecki, J. Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 26, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Buchanan, G.M.; Sadehgi-Azar, L.; Peplau, L.A.; Haselton, M.G.; Berezovskaya, A.; Lipinski, R.E. Desiring the muscular ideal: Men’s body satisfaction in the United States, Ukraine, and Ghana. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2007, 8, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strother, E.; Lemberg, R.; Stanford, S.C.; Turberville, D. Eating Disorders in Men: Underdiagnosed, Undertreated, and Misunderstood. Eat. Disord. 2012, 20, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, G.S.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Halliwell, E. Can appearance conversations explain differences between gay and heterosexual men’s body dissatisfaction? Psychol. Men Masculinity 2014, 15, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunmuga Sundaram, C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Butow, P.N.; Sundaresan, P.; Rutherford, C. A systematic review of body image measures for people diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC). Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3657–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.M.; Brown, D.L. Body image assessment: A review of figural drawing scales. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, J.; Kwakkenbos, L.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Rumsey, N.; Frisén, A.; Brandão, M.P.; Silva, A.G.; Dooley, B.; Rodgers, R.F.; Fitzgerald, A. Systematic review of body image measures. Body Image 2019, 30, 170–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.; Tod, D.; Molnar, G. A systematic review of the drive for muscularity research area. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 7, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.B.; Bulik, C.M. Gender differences in compensatory behaviors, weight and shape salience, and drive for thinness. Eat. Behav. 2004, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmstead, M.P.; Polivy, J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1983, 2, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, N.M.; Hyde, J.S. The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and Validation. Psychol. Women Q. 1996, 20, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.J.; Taylor, M.J.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoi, S.L.; Shields, S.A. The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional Structure and Sex Differences in a College Population. J. Personal. Assess. 1984, 48, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, T.; Langenbucher, J.; Schlundt, D.G. Muscularity concerns among men: Development of attitudinal and perceptual measures. Body Image 2004, 1, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, M.B.; Petrie, T.A. Male body satisfaction: Factorial and construct validity of the Body Parts Satisfaction Scale for men. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Cash, T.F.; Mikulka, P.J. Attitudinal Body-Image Assessment: Factor Analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. J. Personal. Assess. 1990, 55, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, L.; Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N. The Body Appreciation Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2005, 2, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Measure (Studies’ n) | Validation Sample | Psychometrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/Scale | (n) | Gen | Age | Pop | Reliability and Validity |

| Thinness-Oriented (n = 14 depression studies, avg r = 0.30 [men] and 0.32 [women]; n = 5 anxiety studies, avg r = 0.16 [men] and 0.25 [women]; n = 12 self-esteem studies, avg r = −0.25 [men] and −0.40 [women]) | |||||

| Body Dissatisfaction Scale of the Eating Disorder Inventory [41] | (28) | Fem | 20–22 | Clin/Coll | Reliability: High internal consistency in both samples (~0.91). Validity: Criterion (significant mean differences between clinical and non-clinical subsamples) and convergent (high r with other body dissatisfaction measures [0.55 to 0.69]). |

| Concerns, Shape, and Weight Scales of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire [42] | (25) | Fem | 16–35 | Com/Clin | Reliability: Acceptable with high internal consistency in both samples across all scales (0.78 to 0.85). Validity: Criterion (significant mean differences between the community and clinical subsamples). |

| Objectified Body Consciousness Scales: Surveillance, Body Shame, and Control [43] | (16) | Fem | 17–39 | Col | Reliability: Acceptable with high internal consistency across the three scales (0.72 to 0.89). Validity: The scales were negatively correlated with “body esteem”, but the correlations were modest (−0.51) to low (−0.16). |

| Body Shape Questionnaire [44] | (14) | Fem | 20–24 | Com/Clin/Coll | Reliability: Not reported. Validity: Criterion (significant mean differences between the community and clinical subsamples) and convergent (high r with body dissatisfaction measure [0.66]). |

| Factor I of the Eating Attitudes Test [45] | (7) | Fem | 18–25 | Clin/Coll | Reliability: High internal consistency in both subsamples (0.86 to 0.90). Validity: Criterion (significant mean differences between the community and clinical subsamples) and convergent (high r with body image composite [0.61]). |

| Muscularity-Oriented (n = 14 depression studies, avg r = 0.23 [men] and 0.19 [women]; n = 5 anxiety studies, avg r = 0.23 [men] and 0.019 [women]; n = 6 self-esteem studies, avg r = −0.20 [men] and −0.15 [women]) | |||||

| Drive for Muscularity Scale [24] | (51) | Male and Fem | 18–24 | HS | Reliability: High internal consistency (0.84). Validity: Modest convergence with Mental health indicators such as self-esteem (−0.41) and depression (0.32) but small and nonsignificant association with others (e.g., eating disorder symptoms (−0.05); body-image dissatisfaction (−0.15)). |

| Male Body Attitudes Scales: Muscularity, Low Body Fat, and Height [25] | (23) | Male | 16–62 | Col | Reliability: High internal consistency/test–retest reliability for the total (0.91/0.91) and the scales (0.88/0.83 to 0.93/0.94). Validity: Evidence of construct validity with many body-image related measures (0.40 to 0.91), but not always (0.13 to 0.33). |

| Body Esteem (Male) Scales: Physical Attractiveness, Upper Body Strength, Physical Condition [46] | (9) | Male and Fem | nr | Col | Reliability: Adequate to high internal consistency for the scales (0.81 to 0.86). Validity: The individual scales correlated substantively with self-esteem in males (0.45 to 0.51). |

| Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory and Scales: Desire for Size, Appearance Intolerance, and Functional Impairment [47] | (8) | Mal | 18–72 | Com/WL | Reliability: The test–retest reliability was high (0.87). Validity: Evidence of convergent validity with many body-image related measures (0.45 to 0.68), but not always (0.06 to 0.35). |

| Body Parts Satisfaction Scale for Males: Face, Legs, Upper Body [48] | (6) | Mal | 18–22 | Col | Reliability: The internal consistency (0.87 to 0.97) and test–retest reliability (0.58 to 0.94) were high across the scales. Validity: Evidence of convergent validity was mixed (−0.02 to 0.49). |

| Non-Specific concerns (n = 12 depression studies, avg r = 0.34 [men] and 0.29 [women]; n = 5 anxiety studies, avg r = −0.24 [men] and −0.27 [women]; n = 7 self-esteem studies, avg r = −0.55 [men] and −0.57 [women]) | |||||

| Multidimensional Body Self-Relations Questionnaire [49] | (24) | Male and Fem | 15–87 | Com | Reliability: High internal consistency (0.94). Validity: Strong associations with related constructs (0.50 to 0.73). |

| Body Appreciation Scale [50] | (12) | Fem | 18–22 | Col | Reliability: High internal consistency in both subsamples (~0.94). Validity: The scores were positively correlated with appearance evaluation and negatively related to body dissatisfaction for women and men (0.80 to −76). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pomichter, E.; Cepeda-Benito, A.; Ahmadkaraji, S.; DePalma, J.P. Exploring Male Body Image: A Scoping Review of Measurement Approaches and Mental Health Implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060834

Pomichter E, Cepeda-Benito A, Ahmadkaraji S, DePalma JP. Exploring Male Body Image: A Scoping Review of Measurement Approaches and Mental Health Implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060834

Chicago/Turabian StylePomichter, Emily, Antonio Cepeda-Benito, Shahrzad Ahmadkaraji, and John P. DePalma. 2025. "Exploring Male Body Image: A Scoping Review of Measurement Approaches and Mental Health Implications" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060834

APA StylePomichter, E., Cepeda-Benito, A., Ahmadkaraji, S., & DePalma, J. P. (2025). Exploring Male Body Image: A Scoping Review of Measurement Approaches and Mental Health Implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060834