A Review on the Multidisciplinary Approach for Cancer Management in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Focus on Nutritional, Lifestyle and Supportive Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Types of Cancer

- ▪

- Carcinomas: begin in epithelial cells that line internal and external lining of the body; examples include skin, breast, lung, colon, prostate and bladder cancer [15].

- ▪

- Sarcomas: originate from connective or supportive tissues such as bones, tendons, cartilage, muscles, fat or blood vessels [16].

- ▪

- Leukemia: cancer of white blood cells (WBCs); begins in tissues that make blood cells such as the bone marrow and lymphatic system [17].

- ▪

- Lymphomas: cancer in the lymphatic system whereby they begin in lymph nodes and spread to other organs; examples include Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [18].

- ▪

- Myelomas: cancer in the plasma cells of the bone marrow and the cells that make up the immune system [19].

- ▪

- Melanomas: cancer in the skin and which arises from melanocytes, the cells that produce the melanin pigment in the skin.

- ▪

- Central nervous system tumors: cancers originating in the brain and spinal cord [20].

- ▪

- Mixed types: result from the combination of different cancer cell types, often involving both epithelial and mesenchymal cells, and may arise from a complex interplay of factors.

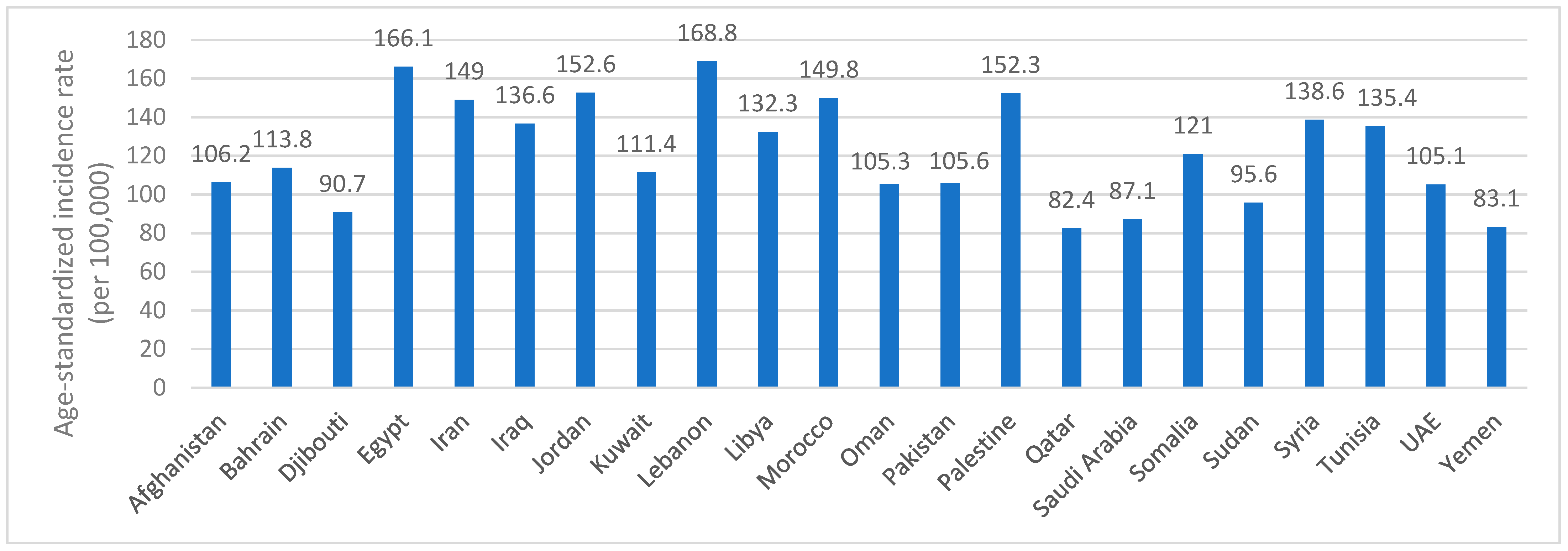

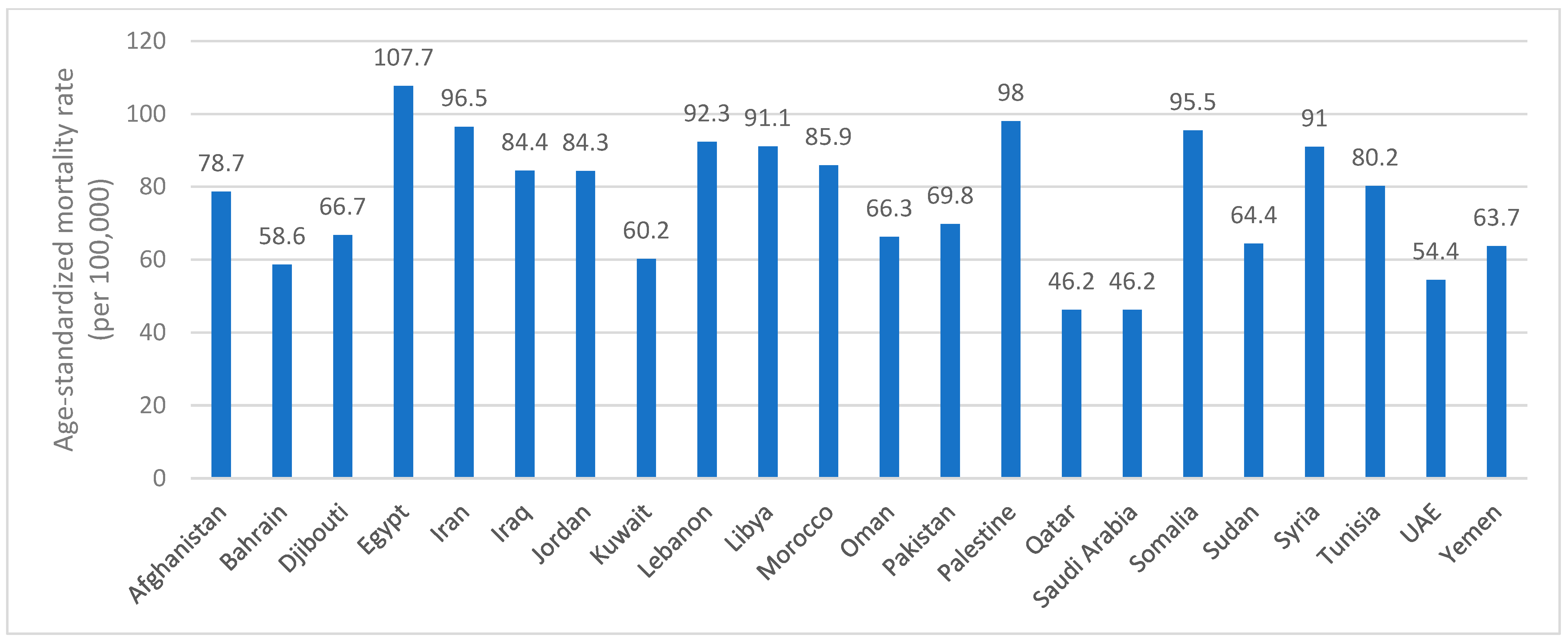

1.2. Global and Regional Prevalence

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Synthesis

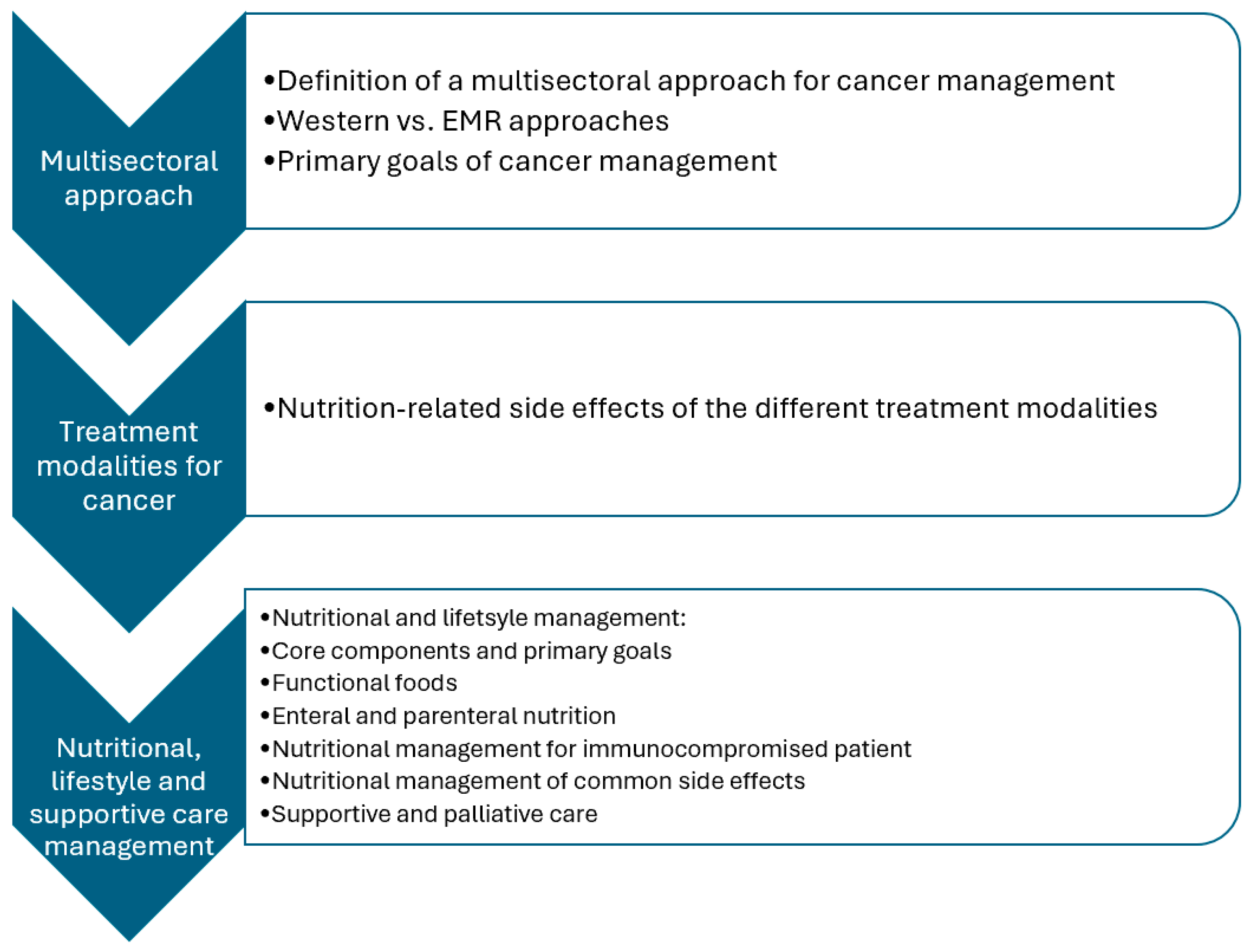

3. Management

3.1. Nutritional and Lifestyle Management

3.2. Core Components

3.3. Primary Goals

3.4. Functional Foods

3.5. Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition

3.6. Nutritional Management for Immunocompromised Patients

3.7. Nutritional Management of Common Side Effects

- Consuming 5–6 smaller, nutrient-rich meals frequently, every 1–2 h, by adapting a schedule to promote adequate oral intake and diet tolerance.

- Establishing regular mealtimes by using a timer rather than relying merely on hunger cues.

- Avoiding meal skipping.

- Consuming the largest meal at the time of the day when appetite is at its peak.

- Keeping nutrient-dense foods such as yogurt, cheeses, nuts and smoothies, always available for snacking.

- Modifying food choices, preparation and presentation of foods and beverages, as needed.

- Trying new dishes and recipes from time to time.

- Having high-energy, high-protein meals and snacks, or considering high-energy and high-protein supplements and smoothies, if needed.

- Having juices or soups whenever solid foods are not well-tolerated.

- Drinking enough liquids. Consuming liquids between meals and throughout the day, rather than during mealtime.

- Developing a pleasant, relaxed and stress-free environment to promote a better meal experience with family, friends and colleagues.

- Engaging in light physical activity as tolerated.

- Offering appetite stimulants/medications when the intake of foods and beverages is not sufficient.

- Examining other factors that may have an impact on appetite, including stress, depression and medications.

- Considering enteral or parenteral nutrition, if needed.

- Consuming 5–6 smaller, frequent meals and snacks a day.

- Having clear liquids such as water, clear broth and electrolytes, for the first 24–48 h after treatment, and then shifting gradually to solid foods (examples include crackers, dry white toasts, cooked white rice or pasta, baked potato, grilled chicken, boiled and plain egg, plain yogurt).

- Avoiding meal skipping.

- Eating and drinking slowly.

- Ensuring the snacks and meals are cool or warm (yet properly cooked) as they may have less odor and are therefore better tolerated.

- Keeping foods covered to prevent exposing their odor.

- Avoiding foods with strong odors like fish, garlic, onions, or having an exhaust fan, or ensuring the patient waits in a distant, well-ventilated room while the food is being prepared.

- Considering dry, starchy foods (such as crackers, white toasts, dry cereals, mashed potatoes and white rice).

- Limiting the intake of acidic foods and beverages.

- Avoiding high-fat, oily, spicy or excessively sweet foods.

- Limiting fiber-rich foods (vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds) and gas-producing foods (such as cruciferous vegetables, raw vegetables including onions, cabbage, broccoli, as well as beans, dairy products with lactose and carbonated beverages).

- Drinking small amounts of clear liquids that are cold or at room temperature to make up for fluid losses.

- Drinking using a straw or directly from a closed cup or bottle to help avoid any odor and to increase the fluid intake.

- Sucking on sugar-free candies to help relieve nausea.

- Consuming bland, soft and easily digestible foods specifically on days of treatment.

- Incorporating complementary therapies such as ginger tea, deep breathing, acupressure bracelets and other relaxation approaches such as reading a book, listening to music and meditating, to aid in the management of symptoms.

- Rinsing the mouth with plain water or baking soda and salt throughout the day.

- Adhering to the prescribed medications for treating nausea.

- Using anti-emetics before meals to provide relief.

- Having the medications with the food rather than on an empty stomach.

- Considering IV fluids or parenteral nutrition when the patient presents with severe vomiting.

- Consuming around 6–8 smaller meals and snacks every 3–4 h.

- Having the meals and snacks at room temperature as they may be more tolerated as such.

- Limiting the intake of high-insoluble fiber foods such as raw vegetables, bran, nuts and seeds.

- Eating high-soluble fiber foods such as pectin-rich fruits (apples, applesauce, bananas), oatmeal, soft white bread, potatoes and white rice; soluble fiber may be beneficial in managing diarrhea.

- Consuming bland foods such as plain rice cakes, plain noodles, plain white pasta, plain white toast, pretzels and crackers.

- Having hydrating beverages and foods like water, broth, gelatine and low-sugar popsicles.

- Avoiding lactose-rich foods and beverages such as dairy products and substituting them with lactose-free options such as unsweetened nut/seed milk and yogurt (soy, almond).

- Avoiding high-fat foods, fried foods, spicy foods and seasonings.

- Avoiding foods with sugar alcohols such as sugar-free candies and gums.

- Aiming for at least 8 cups of fluids a day.

- Limiting the consumption of juices because of their sorbitol content.

- Avoiding caffeine-rich beverages (such as coffee and tea), sugar-sweetened beverages, carbonated beverages and alcoholic drinks.

- Adhering to the prescribed medications for managing diarrhea.

- Having the medications with the food rather than on an empty stomach.

- Considering parenteral nutrition in case oral intake is not well-tolerated.

- Consuming foods that are easy to chew.

- Enjoying soft, moist foods with additional broth, soup, gravies, sauces, dressings or vegetable oils. Avoiding spicy, acidic, seasoned and salty options.

- Trying various food temperatures (warm, cool or chilled) to better identify which temperatures are most soothing and tolerable; yet ensuring foods are consumed at a safe temperature.

- Cutting foods into smaller pieces or blending them to ease swallowing.

- Preparing smoothies using low-acidic fruits such as melon, banana and peaches, and adding yogurt or milk if desired; they are good energy boosters.

- Sucking on low-sugar popsicles or ice chips to numb and ease the mouth or throat pain.

- Limiting the consumption of dry or rough-textured foods like dry toasts, crackers, pretzels, chips, nuts and raw vegetables and citrus fruits and juices.

- Avoiding vinegar, some condiments (pepper, chili, hot sauce), caffeine-rich beverages, carbonated beverages and alcoholic drinks.

- Avoiding foods that may cause irritations in the mouth and throat, such as crunchy foods, sugary foods, spicy foods, acidic foods and seasoned and salted foods.

- Increasing the intake of fluids.

- Drinking with a straw to minimize irritations in the mouth.

- Abstaining from smoking and using tobacco products.

- Rinsing the mouth with plain water or baking soda and salt, and avoiding alcohol-containing mouthwashes, throughout the day.

- Consuming smaller, frequent, easy-to-chew meals and snacks a day.

- Opting for ready-made foods, or foods that are easy to prepare and eat such as tuna, eggs, cheese and crackers, peanut butter and toast, cereal bars and puddings.

- Preparing additional foods, whenever it is most convenient.

- Keeping nutrient-rich foods always available for snacking.

- Having snacks and beverages by the bedside or chairside for easy access.

- Eating when appetite is at its peak.

- Drinking fluids, as much as possible.

- Limiting the consumption of caffeine-rich beverages and alcoholic drinks.

- Requesting support with meal preparation and grocery shopping, from family, friends and colleagues.

- Consulting with the healthcare professional regarding the need for supplements.

- Following good sleeping practices and having a short nap during the day if needed.

- Engaging in daily activities and exercises if tolerated.

- Consulting with a physical therapist for more guidance on exercises to help improve strength and mobility.

- Considering meditation, yoga and stretching exercises, whenever feasible.

- Consulting with the healthcare professional to help treat pain, anxiety or depression, if present.

- Consuming smaller, frequent meals and snacks a day.

- Educating patients on ways to change food texture, temperature or flavor in order to improve their intakes.

- Using plastic utensils when experiencing metallic tastes.

- Having cool foods rather than warm ones, as they may have less odor; yet ensuring foods are consumed at a safe temperature.

- Keeping foods covered to prevent exposing their odor.

- Avoiding foods with strong odors, or having an exhaust fan, or ensuring the patient waits in a distant, well-ventilated room while the food is being prepared.

- Choosing non-meat protein foods such as chicken, turkey, dairy products and legumes, particularly if meat aversions are being experienced.

- Enhancing the flavor of foods or even masking changes in taste by using sauces, marinades, herbs, spices, lemon juice and seasoning blends; yet avoiding the use of onions and garlic because of their strong odor.

- Using flavorings and seasonings to prepare foods.

- Enhancing the flavor of water by using herbs, lemons or fruits.

- Trying citrus fruits to promote saliva production, only in the absence of open sores.

- Enjoying tart foods such as lemon sorbet, citrus fruits, lemonade, dried cranberries, pickles and olives, which may be well-tolerated if sores are not present.

- Using salt to reduce the sweetness of sugary foods.

- Drinking using a straw or directly from a closed cup or bottle to help avoid any odor and to increase the fluid intake.

- Considering the foods and beverages that are more appealing and preferred by the patient.

- Practicing proper oral hygiene by brushing the teeth after meals with a soft toothbrush and by rinsing the mouth with plain water or baking soda and salt, and avoiding alcohol-containing mouthwashes, throughout the day.

- Enjoying soft, moist foods with additional broth, soup, gravies, sauces, dressings or vegetable oils. Avoiding hot, spicy, sour or salty options.

- Soaking foods in liquids to soften them.

- Choosing foods that can be easily swallowed.

- Sucking on low-sugar ice pops, frozen grapes or melon balls.

- Enjoying tart foods such as lemon sorbet, citrus fruits, lemonade, dried cranberries, pickles and olives, for better saliva production, if sores are not present.

- Consuming mashed rice and potatoes, instead of dry bread, toast or crackers.

- Considering liquid nutritional supplements to help meet nutritional needs.

- Limiting foods that may impact the mouth such as hard, hot, spicy, sour, salty or crunchy foods.

- Sipping small amounts of fluids between meals.

- Having a water bottle on-the-go, at all times.

- Avoiding caffeine-rich beverages and alcoholic drinks.

- Abstaining from smoking and using tobacco products.

- Avoiding cariogenic foods such as sweets, candies, cakes, sweet pastries, as well as sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Brushing the teeth after meals with a soft toothbrush and rinsing the mouth with plain water or baking soda and salt, and avoiding alcohol-containing mouthwashes, throughout the day.

- Applying lip balms to moisturize the lips.

- Using a cool mist humidifier when sleeping to increase the moisture in the air.

- Consulting with the healthcare professional regarding the need for medications that may help.

- Consuming 5–6 smaller, frequent meals and snacks a day.

- Modifying food texture, as tolerated.

- Thickening liquids if necessary.

- Cutting foods into smaller pieces or blending them to ease swallowing.

- Considering soft, moist or pureed foods if necessary.

- Adding broth, soup, gravies, sauces, dressings or vegetable oils to moisten dry foods and meals such as meats and cereals. Avoiding spicy and high-acidic options.

- Having high-energy, high-protein meals and snacks, or considering high-energy and high-protein supplements and smoothies, if needed.

- Limiting dry, sharp, crunchy or rough-textured foods such as dry toasts, crackers, pretzels, chips, nuts, raw vegetables and citrus fruits.

- Soaking some dry foods, such as breads or cereals, in milk may help soften them.

- Limiting the consumption of spicy foods, high-acidic foods and beverages such as tomatoes, oranges, lemonades, citrus fruit juices and carbonated beverages.

- Drinking cold beverages or beverages at room temperature.

- Drinking with a straw to minimize irritations in the mouth.

- Avoiding alcoholic drinks.

- Abstaining from smoking and using tobacco products.

- Practicing proper oral hygiene but avoiding alcohol-containing mouthwashes.

- Adhering to the prescribed medications for treating painful swallowing, oral discomfort, esophagitis and/or infection.

- Considering enteral nutrition if needed to provide sufficient intake as long as the patient is unable to consume adequate amounts orally.

- It is recommended to give bisphosphonates or send the patient to the dentist for full dental inspection and care before radiotherapy to the jaw.

3.8. Supportive Care in Cancer Management

3.9. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANH | Artificial nutrition and hydration |

| EMR | Eastern Mediterranean Region |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| IARC | International Agency for Research |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| NOCs | N-nitroso compounds |

| ONSs | Oral nutrition supplements |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| UN | United Nations |

| WBCs | White blood cells |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cancer: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. About Cancer: Understanding Cancer. What Is Cancer? Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Fearon, K.C.; Barber, M.D.; Moses, A.G. The cancer cachexia syndrome. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 10, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattox, T.W. Cancer cachexia: Cause, diagnosis, and treatment. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbemi, A.; Khanna, S.; Njiki, S.; Yedjou, C.G.; Tchounwou, P.B. Impact of gene–environment interactions on cancer development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, P.; Mininni, M.; Deiana, G.; Marino, G.; Divella, R.; Bochicchio, I.; Giuliano, A.; Lapadula, S.; Lettini, A.R.; Sanseverino, F. Healthy lifestyle and cancer risk: Modifiable risk factors to prevent cancer. Nutrients 2024, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. The Cancer Process. Chapter 2 in Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Renehan, A.G.; Roberts, D.L.; Dive, C. Obesity and cancer: Pathophysiological and biological mechanisms. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 114, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Prevention. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/cancer-prevention (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer-Causing Substances in the Environment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: A Global Perspective; World Cancer Research Fund: London, UK; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Research UK. Types of Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/what-is-cancer/how-cancer-starts/types-of-cancer (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Classification. Available online: https://training.seer.cancer.gov/disease/categories/classification.html (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.; Bridge, J.; Hoegendoorn, P. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pui, C.-H.; Evans, W.E. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, S.; Campo, E.; Harris, N.; Jaffe, E.; Pileri, S.; Stein, H.; Thiele, J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, A.; Kenneth, A. Multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro-Oncol 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, S.P.; Mullighan, C.G. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Kruchko, C.; Patil, N.; Tihan, T.; Cioffi, G.; Fuchs, H.E.; Waite, K.A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabello, L.; Troisi, R.J.; Savage, S.A. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Interdiscip Int. J. Am. Cancer Soc. 2009, 115, 1531–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarlock, K.; Meshinchi, S. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: Biology and therapeutic implications of genomic variants. Pediatr. Clin. 2015, 62, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, J.; Morrow, K. Chapter 36: Medical Nutrition Therapy for Cancer Prevention, Treatment, and Survivorship. In Krause and Mahan’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process, 16th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN Cancer Tomorrow. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. SDG Target 3.4. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/sdg-target-3.4-noncommunicable-diseases-and-mental-health (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Cancer: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jawhari, B.; Ludwick, D.; Keenan, L.; Zakus, D.; Hayward, R. Benefits and challenges of EMR implementations in low resource settings: A state-of-the-art review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafer, N.; Gebre, N.; Jabeen, I.; Ashrafizadeh, H.; Rassouli, M.; Mahmoud, L. A model for integrating palliative care into Eastern Mediterranean health systems with a primary care approach. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Types of Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Ben-Arye, E.; Samuels, N.; Daher, M.; Turker, I.; Nimri, O.; Rassouli, M.; Silbermann, M. Integrating complementary and traditional practices in Middle-Eastern supportive cancer care. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2017, 2017, lgx016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbermann, M.; Epner, D.; Charalambous, H.; Baider, L.; Puchalski, C.M.; Balducci, L.; Gultekin, M.; Abdalla, R.; Daher, M.; Al-Tarawneh, M. Promoting new approaches for cancer care in the Middle East. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24 (Suppl. S7), vii5–vii10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoclinic. Cancer: Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cancer/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20370594 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer Treatments. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer-survivors/patients/treatments.html (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- American Cancer Society. How Treatment Is Planned and Scheduled. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/making-treatment-decisions/planning-scheduling-treatment.html (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- De Felice, F.; Malerba, S.; Nardone, V.; Salvestrini, V.; Calomino, N.; Testini, M.; Boccardi, V.; Desideri, I.; Gentili, C.; De Luca, R. Progress and Challenges in Integrating Nutritional Care into Oncology Practice: Results from a National Survey on Behalf of the NutriOnc Research Group. Nutrients 2025, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, E.; Dixon, S.; Claghorn, K.; Levin, R.; Mill, J.; Spees, C. Closing the Gap in Nutrition Care at Outpatient Cancer Centers: Ongoing Initiatives of the Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2018, 118, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasco, P.; Monteiro-Grillo, I.; Camilo, M. Individualized nutrition intervention is of major benefit to colorectal cancer patients: Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of nutritional therapy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Thordardottir, E.; West, C.P.; Jatoi, A. Does dietary counseling improve quality of life in cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Support. Oncol. 2008, 6, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isenring, E.A.; Teleni, L. Nutritional counseling and nutritional supplements: A cornerstone of multidisciplinary cancer care for cachectic patients. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 7, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccagnella, A.; Morello, M.; Da Mosto, M.C.; Baruffi, C.; Marcon, M.L.; Gava, A.; Baggio, V.; Lamon, S.; Babare, R.; Rosti, G. Early nutritional intervention improves treatment tolerance and outcomes in head and neck cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulin, D.; Donadini, A.; Gander, S.; Griesser, A.; Blanc, C.; Hübner, M.; Schäfer, M.; Demartines, N. Cost-effectiveness of the implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol for colorectal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langius, J.A.; Zandbergen, M.C.; Eerenstein, S.E.; van Tulder, M.W.; Leemans, C.R.; Kramer, M.H.; Weijs, P.J. Effect of nutritional interventions on nutritional status, quality of life and mortality in patients with head and neck cancer receiving (chemo) radiotherapy: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison-Jones, V.; West, M. Post-Operative Care of the Cancer Patient: Emphasis on Functional Recovery, Rapid Rescue, and Survivorship. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8575–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Oncology General Guidance; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Therapy Interactions with Foods and Dietary Supplements (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/dietary-interactions-pdq (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- National Cancer Institute. Weight Changes, Malnutrition, and Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/appetite-loss (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Nutrition During Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/nutrition (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Ryan, A.M.; Power, D.G.; Daly, L.; Cushen, S.J.; Bhuachalla, Ē.N.; Prado, C.M. Cancer-associated malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia: The skeleton in the hospital closet 40 years later. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.A.; Clayton, M.F.; Collins, K.K.; Gold, H.T.; Laiyemo, A.O.; Truesdale, K.P.; Ritzwoller, D.P. The Pathways to Prevention program: Nutrition as prevention for improved cancer outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Nutrition in Cancer Care (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/appetite-loss/nutrition-hp-pdq#:~:text=Maintain%20weight.,Produce%20better%20surgical%20outcomes (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- American Cancer Society. Benefits of Good Nutrition During Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/coping/nutrition/benefits.html (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Ravasco, P. Nutrition in cancer patients. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misiąg, W.; Piszczyk, A.; Szymańska-Chabowska, A.; Chabowski, M. Physical activity and cancer care—A review. Cancers 2022, 14, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanpour, M.; Nazer, M.R.; Obeidavi, Z.; Akbari, M.; Ezati, P.; Kor, N.M. Functional foods and their role in cancer prevention and health promotion: A comprehensive review. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 740. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.R.; Siddiqua, T.J. Functional foods in cancer prevention and therapy: Recent epidemiological findings. Funct. Foods Cancer Prev. Ther. 2020, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.; Williams, E. Nutrition support in the oncology setting. In Oncology for Clinical Practice, 2nd ed.; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2021; pp. 218–249. [Google Scholar]

- Doley, J. Enteral nutrition overview. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlana, D. Parenteral nutrition overview. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Pediatric Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Nutrition Support; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Szefel, J.; Kruszewski, W.J.; Buczek, T. Enteral feeding and its impact on the gut immune system and intestinal mucosal barrier. Gastroenterol. Rev. 2015, 10, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland Clinic. Tube Feeding (Enteral Nutrition). Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/21098-tube-feeding--enteral-nutrition (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Cleveland Clinic. Parenteral Nutrition. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22802-parenteral-nutrition (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Macris, P. Chapter 15: Medical nutrition therapy for hematopoietc cell transplantation. In Oncology Nutrition for Clinical Practice, 2nd ed.; Coble Voss, A., Williams, V., Eds.; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2021; pp. 304–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, H.R.; Sadeghi, N.; Agrawal, D.; Johnson, D.H.; Gupta, A. Things we do for no reason: Neutropenic diet. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 13, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Five Keys to Safer Food Manual; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food Safety. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food Safety. Available online: https://www.foodsafety.gov/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Water. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. General Cooking and Food Safety Tips for Cancer; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Food Safety: For Older Adults and People with Cancer, Diabetes, HIV/AIDS, Organ Transplants, and Autoimmune Diseases; Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition: College Park, MD, USA, 2020.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Neutropenia: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145148&ncm_toc_id=145148&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Grant, B.L. American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Nutrition for Cancer Survivors: Eating Well, Staying Well During and After Cancer, 2nd ed.; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Eating Hints: Before, During and After Cancer Treatment; US Department of Health and Human Services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018.

- Elliott, L. Symptom management of cancer therapies. In Oncology Nutrition for Clinical Practice; Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library. ONC: Executive Summary of Recommendations. 2013. Available online: https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5291&cat=5067&ref=E62F2E2D246161DD51AD8B609D4CF7D6D3BF6D6B1A5681E46B3F3CFD42C19974FF33B10EF1662B4980046CA9A25E9C0CA0B7C84D0C1C60A1 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Managing Side Effects of Cancer and Treatment; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Maximizing Nutrition During Cancer Treatment; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R. Managing nutrition impact symptoms of cancer treatment. In Oncology for Clinical Practice, 2nd ed.; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2021; pp. 194–217. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment—Appetite Loss: Nutrition in Cancer Care (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/appetite-loss/nutrition-hp-pdq#cit/section_3.5 (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Nausea and Vomiting: Medical Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145147&ncm_toc_id=270168&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Nausea and Vomiting: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145147&ncm_toc_id=270171&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Nausea and Vomiting Nutrition Therapy; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/client_ed.cfm?ncm_client_ed_id=23 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nausea and Vomiting Nutrition Therapy; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment—Nausea and Vomiting. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/nausea-vomiting (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Diarrhea: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145142&ncm_toc_id=270118&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diarrhea, Bloating, and Stomach Cramps Nutrition Therapy; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment—Diarrhea: Cancer Treatment Side Effect. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/diarrhea (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Diarrhea Nutrition Therapy; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment—Mouth and Throat Problems: Cancer Treatment Side Effects. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/mouth-throat (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Fatigue: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145145&ncm_toc_id=270130&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treatment: Side Effects of Cancer Treatment—Cancer Fatigue. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/fatigue (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Taste and Smell Alterations: Physical Observations; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA; Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145152&ncm_toc_id=270175&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Altered Taste and Smell Nutrition Therapy; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Xerostomia: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA. Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145155&ncm_toc_id=270186&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Care Manual. Oncology: Side Effect Management. Dysphagia: Nutrition Intervention; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Cleveland, OH, USA. Available online: https://www-nutritioncaremanual-org.ezproxy.aub.edu.lb/topic.cfm?ncm_category_id=1&lv1=22938&lv2=145087&lv3=145143&ncm_toc_id=270126&ncm_heading=Nutrition%20Care (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Scotté, F.; Taylor, A.; Davies, A. Supportive care: The “Keystone” of modern oncology practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, R.; Davies, A.; Cooksley, T.; Gralla, R.; Carter, L.; Darlington, E.; Scotté, F.; Higham, C. Supportive care: An indispensable component of modern oncology. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 32, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Palliative Care: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/palliative-care (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- National Institutes of Health and National Cancer Institute. Palliative Care in Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/care-choices/palliative-care-fact-sheet (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. Palliative Care Definition. Available online: https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/definition/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Trentham, K. Nutritional management of oncology patients in palliative and hospice settings. In Oncology Nutrition for Clinical Practice; Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Psychosocial Support Options for People with Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/coping/understanding-psychosocial-support-services.html (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Kesonen, P.; Salminen, L.; Kero, J.; Aappola, J.; Haavisto, E. An integrative review of Interprofessional teamwork and required competence in specialized palliative care. Omega 2022, 89, 1047–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrevall, Y. Nutritional support at the end of life. Nutrition 2015, 31, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of New Cases—2022 (In Thousands) | Number of Deaths—2022 (In Thousands) | Projected Number of New Cases—2050 (In Thousands) | Projected Number of Deaths—2050 (In Thousands) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 130.1 | 52.8 | 401.4 | 186.4 |

| Lung | 54.7 | 49.4 | 133.8 | 125.4 |

| Colorectal | 54 | 30 | 128 | 79.3 |

| Liver | 48.6 | 46.8 | 117.9 | 116.5 |

| Lymphoma | 44.3 | 22.3 | 90.8 | 52.1 |

| Gastric | 37.8 | 31.3 | 101.9 | 87 |

| Leukemia | 34.5 | 25.3 | 65.9 | 54.7 |

| Esophageal | 19 | 17.9 | 46.7 | 46 |

| Pancreatic | 14.1 | 13.4 | 37 | 36 |

| Multiple myeloma | 7.3 | 6.1 | 18.3 | 16.4 |

| Treatment Modality | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|

| Surgery | Common side effects of gastrointestinal (GI) surgeries include early satiety, diarrhea, constipation, nausea and vomiting.Common side effects of head and neck surgeries (particularly in the mouth and pharyngeal regions) include chewing difficulties and dysphagia.Other side effects include fatigue and altered bowel function.GI surgeries mandate nill oral intake post-surgery that could last a few days.

|

| Radiation therapy | Radiation usually causes hair loss and skin changes at the irradiated place. If the radiotherapy is close to the abdominal area, diarrhea, vomiting and loss of appetite might happen. Radiation to the head and neck area leads to mucositis, dysphagia, xerostomia and alterations in taste. Changing the radiation dose or direction might help reduce these side effects. |

| Chemotherapy | Common side effects include early satiety, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, oral sores, alterations in taste, dysphagia, mucositis, infections, hair loss, anemia, loss of appetite, weight loss and anorexia. |

| Immunotherapy | Common side effects include diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, GI perforation, hemorrhage, loss of appetite and anorexia. |

| Hormonal therapy | Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, edema and fluid retention, high cholesterol levels and hyperglycemia, increased appetite and weight gain. |

| Targeted therapy | Common side effects include diarrhea, oral sores and wound-healing difficulties. |

| Hematopoietic cell transplantation | Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, xerostomia, oral sores, altered sense of taste, oral and esophageal mucositis, weight loss and anorexia. |

| Functional Food | Examples of Food Sources |

|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Apples, strawberries, blueberries, cranberries, dark green leafy vegetables, onions, garlic, whole grains, legumes, walnuts, coffee, tea, wine |

| Phenolic acids | Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, soybeans, walnuts, coffee, tea |

| Lycopene | Papaya, pink grapefruit, watermelon, apricots, tomatoes and tomato products |

| Alpha- and beta-carotenes | Mangoes, carrots, pumpkin, green leafy vegetables, sweet potato |

| Anthocyanins | Berries, grapes, plums, purple cabbage |

| Probiotics | Yogurt, fermented foods |

| Resveratrol | Berries, grapes, peanuts |

| Lignans | Whole grains, legumes, flaxseeds, coffee |

| Curcumin | Turmeric |

| General Recommendations | |

| |

| Safe food practices | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Hammerich, A.; Abdulghafar Aldayel, F.; Troisi, G.; Al-Jawaldeh, H.; Aguenaou, H.; Alsawahli, H.; Fadhil, I.; Sohaibani, I.; El Ati, J.; et al. A Review on the Multidisciplinary Approach for Cancer Management in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Focus on Nutritional, Lifestyle and Supportive Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040639

Al-Jawaldeh A, Hammerich A, Abdulghafar Aldayel F, Troisi G, Al-Jawaldeh H, Aguenaou H, Alsawahli H, Fadhil I, Sohaibani I, El Ati J, et al. A Review on the Multidisciplinary Approach for Cancer Management in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Focus on Nutritional, Lifestyle and Supportive Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040639

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Jawaldeh, Ayoub, Asmus Hammerich, Faisal Abdulghafar Aldayel, Giuseppe Troisi, Hanin Al-Jawaldeh, Hassan Aguenaou, Heba Alsawahli, Ibtihal Fadhil, Imen Sohaibani, Jalila El Ati, and et al. 2025. "A Review on the Multidisciplinary Approach for Cancer Management in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Focus on Nutritional, Lifestyle and Supportive Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040639

APA StyleAl-Jawaldeh, A., Hammerich, A., Abdulghafar Aldayel, F., Troisi, G., Al-Jawaldeh, H., Aguenaou, H., Alsawahli, H., Fadhil, I., Sohaibani, I., El Ati, J., Azar, J., Mahmoud, L., Barbar, M., Mqbel Alkhalaf, M., Gafer, N., Mohammed Alghaith, T., Mahdi, Z., & Taktouk, M. (2025). A Review on the Multidisciplinary Approach for Cancer Management in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Focus on Nutritional, Lifestyle and Supportive Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040639