“Stuck Due to COVID”: Applying the Power and Control Model to Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Family Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 and Global Impacts

1.2. COVID-19 and Lockdowns in Australia

1.3. COVID-19 and Family Domestic Violence

1.4. FDV in Australia

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim

2.2. Study Context

2.3. Community-Based Participatory Research Approach

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection

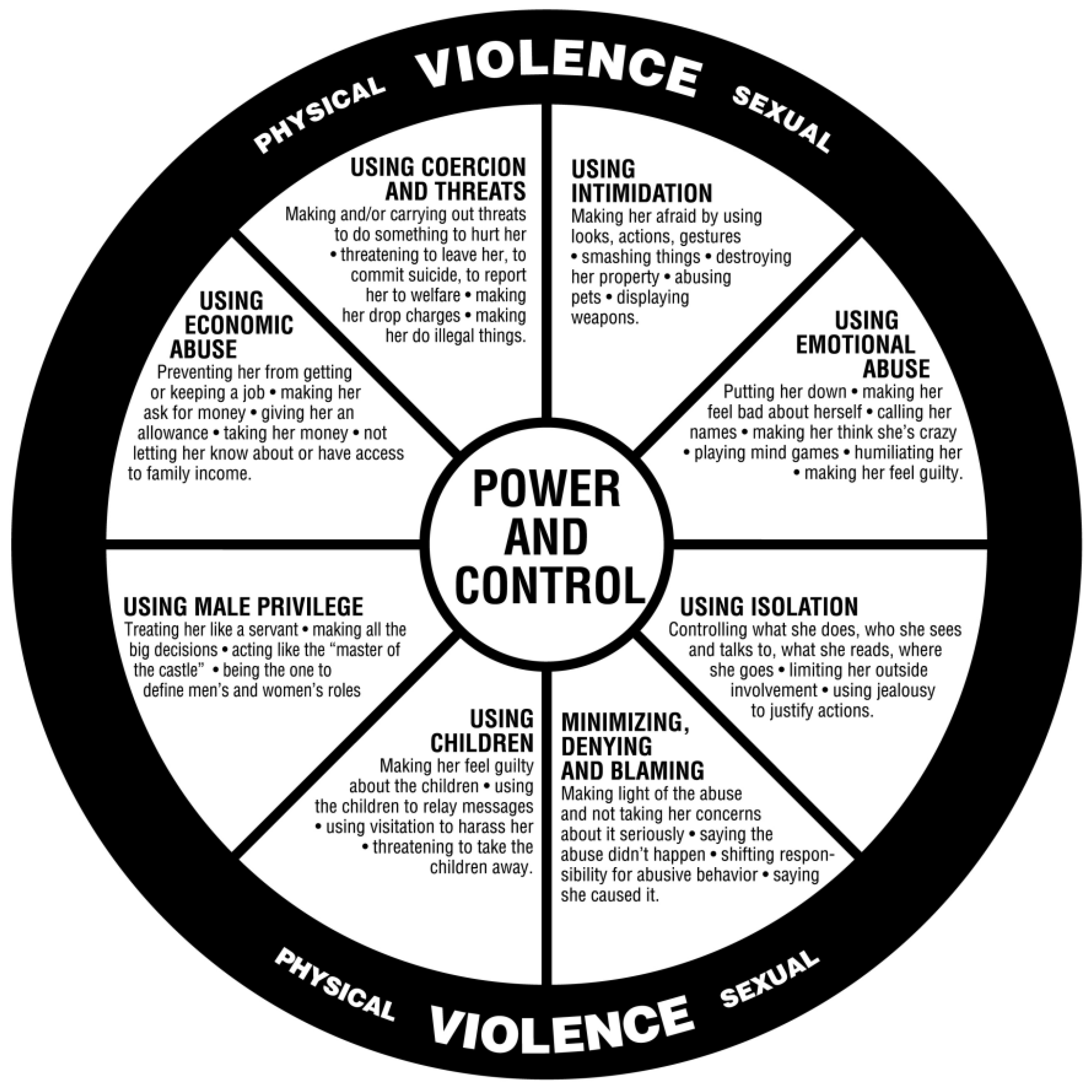

2.6. Power and Control Wheel

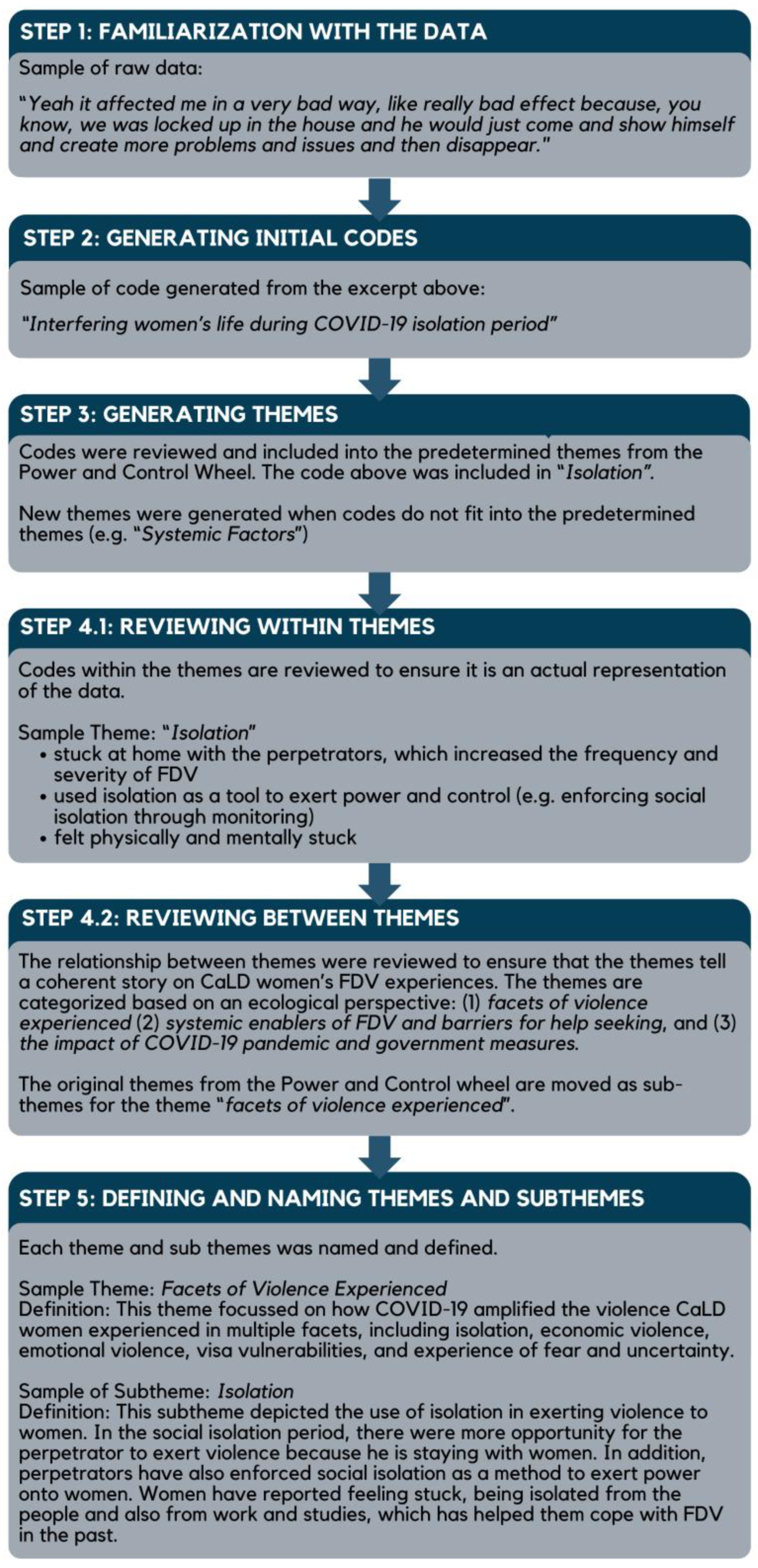

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Reflexivity

2.9. Data Confirmation

2.10. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Adapting the Power and Control Wheel

3.2. Facets of Violence Women Experienced

3.2.1. Isolation

“Yeah it affected me in a very bad way, like really bad effect because, you know, we was locked up in the house and he would just come and show himself and create more problems and issues and then disappear.”(P19)

“We still talk on the phone every single day. She’s my best friend, but it got to the point where I stopped ringing her because I was so skinny [due to the violence]. That she would just panic. And by this stage, we were already in lockdown, and I couldn’t leave the country, and they couldn’t come into the country because of COVID. So she knew that there was nothing that she could do, from [my home country], and I knew that there was nothing that she could do. So I just stopped calling because she was just so worried.”(P13)

“I was away in [my home country] due to the visa issue I couldn’t come and I was stuck with his mother and his mother’s sister at his place back home. So, although it was not mandatory for me [to stay with them], I did it out of goodwill but it kind of turned back on me because I was given COVID by them and they all left me and went to another city…. 21 days of isolation there almost killed me. I used to call my friend and cry daily”.(P2)

3.2.2. Economic Violence

“So COVID came, and, you know how [businesses] had to close down completely. So government been paying us the JobKeeper to keep our businesses. Another fight started there. This money is a lot of money. You should give it to me, I can manage your life. Why are you not letting me manage your life? I said, look, make money, manage your own money and your life. Why are you always want to manage me?”(P3)

3.2.3. Emotional Violence

“I started having symptoms, and they all were in denial. When I asked them that I need to get my COVID test done, they said that you have lots of money to waste, why do you want to get a COVID test done? Because it costed a lot then.”(P2)

“And when it happened, I just went—I was very, very depressed. And they showed no remorse. They were very weird… they said that, you know, I should go home. Why am I acting out?… So I was very angry at that as well.”(P2)

“And because of the lockdown. I was home every day. There was nothing I could do except wait for him to come home and cook for him. That was all I did for a year…I’ve already developed such deep feelings and dependence on him…I didn’t depend on him financially, but emotionally. Because he was the only thing in your [my] world for a whole year…we had to make up because it felt like if I lost him, I lost my world.”(P23)

3.2.4. Visa Vulnerabilities

“I didn’t know if I could stay because of the permanent residency…I was panicking inside every day. You’re anxious and you don’t know what tomorrow’s like. I was on a tourist visa and I only had three months. I had to keep extending it. Who knew what was going to happen—next? And I have asthma, so before—without the vaccination—if COVID came back home, I was led to believe that it would be really severe for me.”(P23)

“[I] don’t have any single thing. I asked him that I left my—some of my sweaters and shawls and everything. Can you please give me one of them? He said, I threw all of your luggage outside. I don’t have any single thing of yours in my room. He already threw it. Because he knew that [I] can’t come in. That’s the pandemic days. No flight will come. And my visa was about to finish.”(P21)

“I couldn’t stay with my cousins because they all are males…I said to my cousin that-that you can stay inside [the house] and I can like, stay outside in your car, but I can’t stay alone with you all men. Because I was very, very stressed.”(P21)

3.2.5. Experiences of Fear and Uncertainty

“I was telling him, you’ve been exposed out and he was like, so what and he was coming and grabbing my son and he was kissing top to toe, like, now your mummy get COVID too, like that’s how he was acting.”(P3)

“I thought maybe I wouldn’t survive just because of this… condition, he would… make me die and everyone would say oh she died because of COVID. No one would come to know why I died.”(P5)

“I think the fear I had during COVID, it added up more when the DV happened…I was constantly in flight or fight mode. I was constantly scared. What’s gonna happen next? What’s gonna happen? Am I gonna get punched today? Am I gonna get shouted? I’m like that every day now.”(P25)

“I’m very careful. I don’t trust people. I’m very scared…because of what happened, I just don’t want anybody to come in…If someone comes and says…we [will] help you. I’ll always ask, are you for real? What do you want in return from me? I’m scared. And the police are saying, no, we are here to help. They’re genuine.”(P25)

3.3. Systemic Enablers of FDV and Barriers to Help Seeking

3.3.1. FDV Service Provision

“And many of the organisations taking excuse, or this is COVID time so we can’t do it. We can’t give you appointment, this is delay, pandemic effect was delaying of the things because even it is very safe to talk... they could put mask, sanitiser was there. A lot of things you can take care of while doing but still organisation was making excuse the pandemic.”(P5)

3.3.2. Immigration System

“I called the suicidal hotline a few times because I just felt so helpless…The first time, I hung up briefly, because back then I wasn’t a permanent residency yet. It came to mind that actually your mental health will impact your ability to obtain a permanent residency. Your visa could get rejected based on severe mental health conditions. So nobody wants to take the risk.”(P23)

3.4. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Government Measures on Women and Families

3.4.1. COVID-19 Pandemic Enabling FDV

“His mum passed away during the COVID time. And he couldn’t go back to [home country]. He seems very—[Interviewer: Upset with that.] Yeah. Upset with that. And then when he has a delusion—he taking the marijuana, and then he keeps saying his mom’s still alive, and we trying to cheat him, say his mom passed away. He opened all the windows and doors, just say, oh my mom is coming, something like that…I think if at that time my husband was able to visit his families in overseas, the things may be a little bit different.”(P11)

“He was at breaking point with work and I think that contributed to us separating because his workload tripled. So where most people were laid off, and he was working from home, I’m studying from home, the kids were off school. I was still expected to do everything I did while he was just working all the time on his computer seven o’clock till seven…and I think that was a big contribution to us separating. It was a huge stress for us… He was under an enormous amount of pressure and something had to give and unfortunately it was me.”(P7)

3.4.2. COVID-19 Pandemic Reducing the Impact of FDV

“I remember that it was actually quite positive because when all of the bars shut, it meant that he couldn’t go out drinking… So he stayed at home. You know, so at least I knew where he was. So that some of the lockdowns actually benefited me because he couldn’t go missing for five days.”(P13)

“And I would take that in a very positive way because I think it was a point where we all realized that, okay, family’s more important… So I think COVID has given us a lot of eye-opening points as well in our lives where we realised that—what is the priority and what’s not.”(P1)

3.4.3. COVID-19 Pandemic Paled into Insignificance

“Well there’s nothing specific for me, during the pandemic, it’s still the same, you know, as it was before pandemic or after pandemic. It’s just him. There is no other problem in my life. It’s just my ex is the biggest problem.”(P15)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. The Experience of Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic from CaLD Women’s Perspectives

4.3. The Experience of Violence Post COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. Experiences of CaLD Women in WA in Comparison to Other Countries

4.5. Implications and Recommendations

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Msemburi, W.; Karlinsky, A.; Knutson, V.; Aleshin-Guendel, S.; Chatterji, S.; Wakefield, J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long covid—Mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, L.; Temerev, A.; Flahault, A. Comparing the scope and efficacy of COVID-19 response strategies in 16 countries: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrofi, M.M.; Mahama, M.; Nevo, C.M. Nexus between the gendered socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 and climate change: Implications for pandemic recovery. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.J.; Dri, G.G.; Logan, P.; Tan, J.B.; Flahault, A. COVID-19 down under: Australia’s initial pandemic experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Tallon, M.; Smith, T.; Jones, L.; Mörelius, E. COVID-19 in Western Australia: ‘The last straw’ and hopes for a ‘new normal’ for parents of children with long-term conditions. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, N. Understanding Experiences and Impacts of COVID-19 on Individuals with Mental Health and AOD Issues from CaLD Communities; Mental Health Commission: Perth, Australia, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bhoyroo, R.; Chivers, P.; Millar, L.; Bulsara, C.; Piggott, B.; Lambert, M.; Codde, J. Life in a time of COVID: A mixed method study of the changes in lifestyle, mental and psychosocial health during and after lockdown in Western Australians. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Western Australia. COVID-19 Coronavirus: Declarations. 2022. Available online: https://www.wa.gov.au/government/document-collections/covid-19-coronavirus-declarations (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Sarasjarvi, K.K.; Chivers, P.; Bhoyroo, R.; Codde, J. Bouncing back from COVID-19: A Western Australian community perspective. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1216027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.; Dembele, L.; Dawes, C.; Jane, S.; Macmillan, L. The Australian National Research Agenda to End Violence against Women and Children (ANRA) 2023–2028; Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Limited (ANROWS): Sydney, Australia, 2023; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Government. COVID-19 Response Inquiry Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/resources/covid-19-response-inquiry-report (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Smyth, C.; Cullen, P.; Breckenridge, J.; Cortis, N.; Valentine, K. COVID-19 lockdowns, intimate partner violence and coercive control. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 56, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, E.; Lotta, G.; Fernandez, M.; Herten-Crabb, A.; Mac Fehr, L.; Maple, J.-L.; Paina, L.; Wenham, C.; Willis, K. SDG5 “Gender Equality” and the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid assessment of health system responses in selected upper-middle and high-income countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1078008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence. 2023. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/types-of-violence/family-domestic-violence (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- UN Women. Press Release: UN Women Raises Awareness of the Shadow Pandemic of Violence Against Women During COVID-19; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, M.; Rubini, E.; Bahattab, A.; Loddo, M.; Della Corte, F.; Ragazzoni, L.; Valente, M. Vulnerability of migrant women during disasters: A scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillimore, J.; Pertek, S.; Akyuz, S.; Darkal, H.; Hourani, J.; McKnight, P.; Ozcurumez, S.; Taal, S. “We are Forgotten”: Forced migration, sexual and gender-based violence, and Coronavirus Disease-2019. Violence Against Women 2021, 28, 2204–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.L.; Berecki-Gisolf, J.; Clapperton, A.; O’Brien, K.S.; Liu, S.; Gibson, K. Definitions of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD): A Literature Review of Epidemiological Research in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennewell, C.; Shaw, B.J. Perth, Western Australia. Cities 2008, 25, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, T.; Islam, N.; Tandon, D.; Ho-Asjoe, H.; Rey, M. Using community-based participatory research as a guiding framework for health disparities research centers. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2007, 1, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Greater Perth 2021 Census All Persons QuickStats. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/5GPER (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Jiménez-Chávez, J.C.; Rosario-Maldonado, F.J.; Torres, J.A.; Ramos-Lucca, A.; Castro-Figueroa, E.M.; Santiago, L. Assessing acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary effectiveness of a community-based participatory research curriculum for community members: A contribution to the development of a community-academia research partnership. Health Equity 2018, 2, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.B.; Duran, B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. (Ed.) Doing research in a cross-cultural context: Methodological and ethical challenges. In Doing Cross-Cultural Research: Ethical and Methodological Perspectives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. 2020. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- McAlpine, L. Why might you use narrative methodology? A story about narrative. Eest. Haridusteaduste Ajak. Est. J. Educ. 2016, 4, 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) Introduction: The discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research, in Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs. Understanding the Power and Control Wheel. 2017. Available online: https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wheels/faqs-about-the-wheels/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Rankine, J.; Percival, T.; Finau, E.; Hope, L.; Kingi, P.; Peteru, M.C.; Powell, E.; Robati-Mani, R.; Selu, E. Pacific peoples, violence, and the Power and Control Wheel. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 2777–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, H.L.; Bonomi, A.E.; Mass, M.K.; Bogen, K.W.; O’Malley, T.L. #MaybeHeDoesntHitYou: Social media underscore the realities of intimate partner violence. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 885–891. [Google Scholar]

- Paymar, M.; Barnes, G. Countering Confusion About the Duluth Model; Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs: Duluth, MN, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CounteringConfusion.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Volpp, L. Working with Battered Immigrant Women: A Handbook to Make Services Accessible; Marin, L., Ed.; Family Violence Prevention Fund: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. NVivo 14. 2023. Available online: https://support.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/s/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 2022, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleth, M.; Serova, N.; Trojanowska, B.K. Prevention and Safer Pathways to Services for Migrant and Refugee Communities: Ten Research Insights from the Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Projects with Action Research (CALD PAR) Initiative (ANROWS Insights, 01/2020); ANROWS: Sydney, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/prevention-of-violence-against-women-and-safer-pathways-to-service/ (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Clark-Kazak, C. Ethical considerations: Research with people in situations of forced migration. Refuge 2017, 33, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. The Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Usher, K.; Jones, C.B.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Fatema Jackson, D. COVID-19 and family violence: Is this a perfect storm? Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, M.; Brewer, G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sower, E.A.; Alexander, A.A. The same dynamics, different tactics: Domestic violence during COVID-19. Violence Gend. 2021, 8, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentaraki, M.; Speake, J. Domestic violence in a COVID-19 context: Exploring emerging issues through a systematic analysis of the literature. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrave, M.; Maher, J. Coronavirus: Family Violence and Temporary Migration in the Time of COVID-19. Monash Lens, Monash University, 2020. Available online: https://lens.monash.edu/@marie-segrave/2020/04/02/1379949/coronavirus-family-violence-and-temporary-migration-in-the-time-of-covid-19 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Letourneau, N.; Luis, M.A.; Kurbatfinski, S.; Ferrar, H.J.; Pohl, C.; Marabotti, F.; Hayden, K.A. COVID-19 and family violence: A rapid review of literature published up to 1 year after the pandemic declaration. eClinical Med. 2022, 53, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Crowe, M.; Cleak, H.; Kallianis, V.; Braddy, L. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients experiencing family violence presenting to an Australian health service. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2022, 53, 1161–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrave, M.; Pfitzner, N. Family Violence and Temporary Visa Holders During COVID-19; Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, H.; Roman, B.; Mahmoud, A.; Boyle, C. Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant and Refugee Women and Children Experiencing DFV; Women’s Safety NSW: New South Wales, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Segrave, M.; Wickes, R.; Keel, C. Migrant and Refugee Women in Australia: The Safety and Security Survey; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, K.; Morley, C.; Warren, S.; Ryan, V.; Ball, M.; Clarke, J.; Vitis, L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Australian domestic and family violence services and their clients. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 56, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, A.; Lee, R.C.; Rojas-Guyler, L.; Lambert, J.; Smith, C.R. The influences of sociocultural norms on women’s decision to disclose intimate partner violence: Integrative review. Nurs. Inq. 2023, 30, e12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawrikar, P.; Katz, I. Recommendations for improving cultural competency when working with ethnic minority families in child protection systems in Australia. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2014, 31, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, R.P. Cultural collectivism, intimate partner violence, and women’s mental health: An analysis of data from 151 countries. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 1125771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Grossman, S.; Perkins, N. The effects of COVID-19 on domestic violence and immigrant families. Greenwich Soc. Work. Rev. 2020, 2, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Mangahas, X.; Nimmo, J. Domestic and Family Violence in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CaLD) Communities; Pro Bono Centre, The University of Queensland Australia: Brisbane, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, N.; Rai, A. Every cloud has a silver lining but… Pathways to seeking formal-help and South Asian immigrant women survivors of intimate partner violence. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 1170–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, C.; Carrington, K.; Ryan, V.; Warren, S.; Clarke, J.; Ball, M.; Vitis, L. Locked down with the perpetrator: The hidden impacts of Covid-19 on domestic and family violence in Australia. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2021, 10, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, R.; Robinson, K. Domestic and family violence for culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia during Covid-19 pandemic. Soc. Work. Action 2023, 35, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Satyen, L.; Toumbourou, J.W. Influence of cultural norms on formal service engagement among survivors of intimate partner violence: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024, 25, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Medicare. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/medicare?language=und (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence: FDSV and COVID-19. 2023. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/responses-and-outcomes/covid-19 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- McKibbin, G.; Humphreys, C.; Gallois, E.; Robinson, M.; Sijnja, J.; Yeung, J.; Goodbourn, R. “Never Waste a Crisis”: Domestic and Family Violence Policy and Practice Initiatives in Response to COVID-19; ANROWS: Sydney, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/never-waste-a-crisis-domestic-and-family-violence-policy-and-practice-initiatives-in-response-to-covid-19/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Pacheco, Y.J.O.; Toncel, V.I.B. Violence against women in the post-pandemic time of COVID-19. Aten. Primaria 2024, 29, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwegwe, E. A quarantine paradox: Understanding Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in post-COVID-19 era: Insights from Golden Valley mining community, Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, J.; Silva, A.L.; Gonçalves, M. Intimate Partner Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study About Dynamics and Help-Seeking Experiences of Immigrant Women in Portugal. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, B.; Hartley, M.; Saha, J.; Murray, S.; Glass, N.; Campbell, J.C. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on women’s health and safety: A study of immigrant survivors of intimate partner violence. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 1294–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, A.; Seff, I.; Caron, C.; Maglietti, M.M.; Erskine, D.; Poulton, C.; Stark, L. “The pandemic made us stop and think about who we are and what we want:” Using intersectionality to understand migrant and refugee women’s experiences of gender-based violence during COVID-19. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Majumder, M. Where is my home?: Gendered precarity and the experience of COVID-19 among women migrant workers from Delhi and National Capital Region, India. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E.; Fernado, T.; Gassner, L.; Hill, J.; Seidler, Z.; Summers, A. Unlocking the Prevention Potential: Accelerating Action to End Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence. Report of the Rapid Review of Prevention Approaches. 2024. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/resources/unlocking-the-prevention-potential (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Davies, S.E.; di Piramo, D. Spotlight on the gendered impacts of COVID-19 in Australia: A gender matrix analysis. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2022, 28, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Borah, S.B. COVID-19 and domestic violence: An indirect path to social and economic crisis. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffsky, R.; Beek, K.; Wayland, S.; Shanthosh, J.; Henry, A.; Cullen, P. “The real pandemic’s been there forever”: Qualitative perspectives of domestic and family violence workforce in Australia during COVID-19. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, N.; Fitz-Gibbon, K.; Meyer, S.; True, J. Responding to Queensland’s ‘Shadow Pandemic’ During the Period of COVID-19 Restrictions: Practitioner Views on the Nature of and Responses to Violence Against Women; Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre: Victoria, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.genderandcovid-19.org/resources/responding-to-queenslands-shadow-pandemic-during-the-period-of-covid-19-restrictions-practitioner-views-on-the-nature-of-and-responses-to-violence-against-women/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Australian Government. Domestic and Family Violence and Your Visa. Available online: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/domestic-family-violence-and-your-visa/family-violence-provisions (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Fair Agenda. Federal Budget 2024: It Leaves Gaping Holes in the Service Safety Net Women Need for Their Safety. Available online: https://www.fairagenda.org/2024budget (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence: How Do People Respond to FDSV. 2024. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/responses-and-outcomes/how-do-people-respond-to-fdsv (accessed on 1 April 2024).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | |

| Pakistan | 6 (22.2) |

| China | 2 (7.4) |

| India | 2 (7.4) |

| Iran | 2 (7.4) |

| Other | 13 (48.1) |

| Missing | 2 (7.4) |

| Arrival visa | |

| Partner visa | 10 (37) |

| Student visa | 5 (18.5) |

| Working Holiday visa | 2 (7.4) |

| Visitor visa | 2 (7.4) |

| Humanitarian visa | 1 (3.7) |

| Skilled Independent visa | 1 (3.7) |

| Other | 5 (18.5) |

| Does not know | 1 (3.7) |

| Number of years in Australia | |

| 1–2 years | 6 (22.2) |

| 3–5 years | 4 (14.8) |

| 6–9 years | 5 (18.5) |

| 10 or more years | 13 (44.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 3 (11.1) |

| Separated | 13 (48.1) |

| Divorced | 7 (25.9) |

| Widowed | 1 (3.7) |

| Never married | 2 (7.4) |

| Missing | 1 (3.7) |

| Number of children | |

| None | 8 (29.6) |

| One | 10 (37) |

| Two | 7 (25.9) |

| Three or more | 2 (7.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo, A.; Griffin, G.; Byambadash, H.; Mitchell, E.; Dantas, J.A.R. “Stuck Due to COVID”: Applying the Power and Control Model to Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Family Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040627

Lo A, Griffin G, Byambadash H, Mitchell E, Dantas JAR. “Stuck Due to COVID”: Applying the Power and Control Model to Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Family Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040627

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo, Azriel, Georgia Griffin, Hana Byambadash, Erin Mitchell, and Jaya A. R. Dantas. 2025. "“Stuck Due to COVID”: Applying the Power and Control Model to Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Family Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040627

APA StyleLo, A., Griffin, G., Byambadash, H., Mitchell, E., & Dantas, J. A. R. (2025). “Stuck Due to COVID”: Applying the Power and Control Model to Migrant and Refugee Women’s Experiences of Family Domestic Violence in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040627