Vulnerability and Complexity: Wartime Experiences of Arab Women During the Perinatal Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

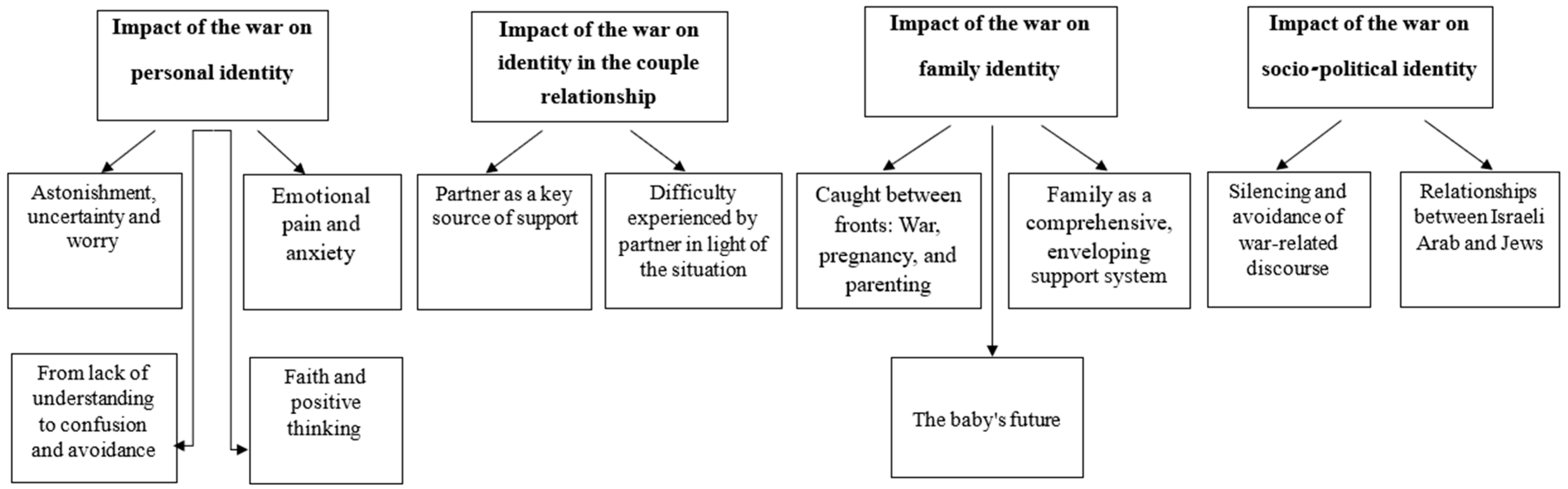

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Impact of the War on Personal Identity

3.1.1. Subtheme 1.1. Astonishment, Uncertainty, and Worry

“Perhaps this is a situation that has opened the door to hell for us, we are entering the unknown and there is doubt about what we will do and what will happen in future… The country has no answers at all to where all this is going”.(Interviewee 1)

“You put the worst-case scenario in front of you. Like, is there a chance that a major war will break out? Your thoughts go to the farthest places…Where will this lead us? It was clear that [the event] this time is different [from events] that preceded it. Therefore, we didn’t know when it would end, where it would lead, and how the situation would look”.(Interviewee 5)

“I am more afraid about what will happen… They are talking everywhere saying this is the beginning of a world war. It could be or not, no one knows, and if it starts—what will happen to us?”.(Interviewee 3)

“I felt worried, about how to continue living, what will happen to the girl [daughter], where will she go?”.(Interviewee 4)

“This situation is scary and worrying… war, when you hear about it for the first time, there is great fear”.(Interviewee 9)

3.1.2. Subtheme 1.2. Emotional Pain and Anxiety

“…there’s also pain for every person who has died without fighting, to give legitimacy to killing people is not human… there was pain from the consequences of the subject”.(Interviewee 1)

“It wasn’t easy, and I also, in the initial period… in the first 3–4 days of this period, I had a very hard time… an unpleasant feeling, I felt anger and nervousness”.(Interviewee 3)

“I was scared, I was anxious, I felt it wasn’t like always, this time I felt it was completely different…”.(Interviewee 8)

“There was stress and fear at the same time. Stress because nothing is known because we are going to an unknown place”.(Interviewee 5)

3.1.3. Subtheme 1.3. From Lack of Understanding to Confusion and Avoidance

“I felt that I was in a dream”.(Interviewee 2)

“As if a person was astonished and trying to understand what is happening and doesn’t understand, that is, fell asleep and woke up to the Holocaust. It was very difficult”.(Interviewee 3)

“When I read [the messages] I didn’t understand exactly what it was because of the size of the event. I didn’t understand whether the events described were true or were a prank. My husband came and explained it to me. I remember that I couldn’t absorb what he said, I managed to fully digest what happened only after one, two, three days… I managed to understand what’s happening and to understand the situation the country is in”.(Interviewee 7)

“It was very difficult… I even felt that I had no appetite and lost weight… I was very affected… I would watch the news or read the news and then I decided to stop. Even today I don’t see anything on the news…”.(Interviewee 10)

“I followed everything during the first three days until I decided to stop watching the news. After that, I decided to only follow updates on Facebook or social media. Recently, I decided to give up on social media too and not to know anything”.(Interviewee 3)

“The best step I took was deleting Instagram, to let myself breathe, and not to bring in negative energy, not into the home and not to my daughter, because I’m one of those people who those videos impact, and those stories that a mother lost her child and baby impact me a lot. It’s very hard for me and therefore, that’s it, I deleted it”.(Interviewee 4)

“Currently I don’t watch the news. I am immediately hurt when I see the news, even my husband opens his telephone and watches the news or television at my uncle’s house and also at my parents’ house—the same thing and loudly, everyone follows the news throughout the day. It disturbs me emotionally, I am exhausted, so I asked them to change the channel—and if it’s on the phone—to skip over it”.(Interviewee 6)

“The more I watched the news, I would cry and cry and cry until I set a boundary for myself that I am forbidden to watch the news anymore. Enough…”.(Interviewee 7)

3.1.4. Subtheme 1.4. Faith and Positive Thinking

“Nothing else will help us, other than strengthening ourselves with positive talk. To sit and say that things won’t work out—we will harm ourselves emotionally, and that will go against us. We need to strengthen ourselves with positive talk and in the end, everything will pass”.(Interviewee 6)

“I am usually a positive person. I never perceived myself as someone who thinks negatively. Many times, just the positive thoughts [help]. If something [bad] is going to happen, then it will happen, there is no way to prevent it. These are things that helped. Also sport”.(Interviewee 2)

“I would read the Quran a lot, that’s what helped me”.(Interviewee 4)

“I started to pray and told myself that everything is written by our God… Everything is in God’s hands… He gave me the faith and thus the fear diminished and calmed the soul”.(Interviewee 8)

3.2. Theme 2: Impact of the War on Identity in the Couple’s Relationship

3.2.1. Subtheme 2.1. Partner as a Key Source of Support

“Thank God, I have my partner [said with a smile], he supports me at every moment, I always share everything with him. It helps me”.(Interviewee 2)

“The first one to support me is my husband. He is the first person who is with me at home, it’s also my personal opinion that if the husband is supportive—then it’s enough. My husband helps me with housework and takes me out of the house—even if it’s half an hour… he shares other things with me, prepares food and everything”.(Interviewee 3)

“The one who helps me the most, and the most important, is my partner. He helps me in the house and with the girls, and [we] also talk to each other, which lowers [the pressure] on me a bit. We are both suffering from the same complexity”.(Interviewee 5)

“What most helps me is my husband thank God. He helps me, supports me, and accepts me… and even appreciates me more when he sees how much the woman suffers during pregnancy. [He asks] what I am lacking, what I want… he is always considerate in these matters, especially the appointments with the doctors. At first, he would make the appointments”.(Interviewee 6)

“My husband was with me in everything. He takes her [the baby] from me at night to let me sleep from 22:00 until the morning, and that is daily and not one day yes one day no. I am telling you honestly, every day—he would take her”.(Interviewee 4)

3.2.2. Subtheme 2.2. The Need to Support the Partner in Light of the Situation

“… He had a whole week where he lay in bed. He didn’t do anything; he didn’t even eat and barely drank some sage tea… I started to keep my distance from him… I started to tell him that I didn’t want to see you in this state… I try to take pressure off him, like payments, or I don’t tell him that I want to buy a certain item of clothing or things that I can live without. I can help him and help myself; the main thing is that this period doesn’t hurt me or the little girl”.(Interviewee 4)

“I see that he is stressed. Also economically, because he wants to ensure all our needs and our son’s [needs]. This is the most important thing, he doesn’t want to be in a place where he can’t meet our needs, because then he is under stress and pressure. He tries not to show me, but I feel it. When I share with him, I do it calmly, because I don’t want to pressure him more. I always wish him success and try to raise his spirits with positive things”.(Interviewee 6)

“The people at my husband’s work come from faraway places… then he had to be in their place, and he was away from home for more hours. This increased his stress at home, he felt more responsible and nervous, was busier, and was dominated by feelings of pressure and fear…”.(Interviewee 9)

3.3. Theme 3: Impact of the War on Family Identity

3.3.1. Subtheme 3.1. Caught Between Fronts: War, Pregnancy, and Parenting

“I don’t know how long the war will continue or what will happen when I give birth… At some point, I said to myself that everything was messed up. Just thinking about it is exhausting. In the meantime, I am not functioning with my daughters because my thoughts are constantly at work, and also because I’m tired. I am not managing to focus on the pregnancy because of the situation and because of my daughters… I feel as if I’m torn between several spaces and at the same time I don’t know where I am standing”.(Interviewee 5)

“…In those days I didn’t even remember I was pregnant; I forgot about it. Sometimes I felt guilty, because I’m also responsible for another soul [the fetus], someone also needs to worry about her. Despite this, I was forced to cope with events that were larger than me… [when] there’s another child with you in the house—it’s much more frightening… even with the return to educational frameworks to routine two weeks ago, my fear grew… the educational frameworks in it aren’t set up and they aren’t prepared for emergencies, so, until they [the local council] take care of things, I have to cope with the question—where should I leave my daughter when I go to work?”.(Interviewee 2)

“…Usually, a pregnant woman’s hormones change and she is afraid to give birth. Following the events, I don’t ask how I will give birth, but what will happen to my children?… How will I deal with the safety issues? If I want to leave the house and the birth process begins to happen, what will I do?….(Interviewee 9)

3.3.2. Subtheme 3.2. Family as a Comprehensive Enveloping Support System

“When I’m stressed, I meet my parents, they calm me down, stand by my side and understand me. When they are next to me, I feel support and strength and am not afraid… I get my strength from them”.(Interviewee 10)

“My mother comes and helps me prepare food and also with the housework, on an emotional level they (the parents) always talk to me and calm me down… One day I was sitting with my husband’s parents in the yard, and we heard the sirens. I felt that everyone was concerned first of all that I would be safe… I felt that I had an escort and I was not alone…”.(Interviewee 8)

“My husband’s parents live below us in the same building. They supported me a lot, tried to help with tasks that I needed to do at home, and did things for me so that I could rest and not exert myself. My husband and I are from the same town, and my parents live in the same town. They also helped me a lot, they came to my house, checked if I needed anything, invited me to come to their house to change the atmosphere a little sometimes”.(Interviewee 3)

“On the days when my husband slept outside the home, I was afraid to stay at home alone, at least in the beginning. Therefore, I used to sleep at my parents’ house until the whole period passed. I have an excellent relationship with my mother and with my sister. This makes it easier for me to share with them”.(Interviewee 2)

3.3.3. Subtheme 3.3. The Baby’s Future

“I thought to myself—how will my daughter grow up? How will she live? What if she is exposed to hatred? What if someone treats her with racism? How will she cope with this?”.(Interviewee 7)

“It’s a sense of fear for her… I love her [her daughter] and want her to stay with me, so I am always afraid for her. It’s like, she is mine, born from God, I don’t trust someone else to raise her or to do something for her. There was great fear—and now anything I do—I take her with me: in the shower, in the toilet, to bathe, to cook, and even to sleep. I don’t even want to close my eyes… I didn’t sleep at all for several days so that she would be next to me, and I would protect her”.(Interviewee 1)

“What scares me the most is what will happen to my children. I want my son to be born into a safe atmosphere, with less conflict between Arabs and Jews… I want him to be born in an atmosphere that isn’t dangerous… That he will live in stability, that I won’t be afraid for him. My son is the most important to me in life, I don’t want him to arrive in stress”.(Interviewee 6)

3.4. Theme 4: Impact of the War on Socio-Political Identity

3.4.1. Subtheme 4.1. Silencing and Avoidance of War-Related Discourse

“If someone asks me any question about the war, I will not answer him. I prefer to be distant. The solution is—not to talk about this subject”.(Interviewee 3)

“How should I answer someone who makes extreme statements in front of me? Or is it preferable not to answer at all? Before [the war], I would answer regularly, not extremely, but I did have the possibility of answering him in a respectful and understanding way. However, this war is different. [During] this war, it’s preferable not to answer at all, it’s preferable not to speak. This war changed the balance [of power]. It is not similar to what was before. Before this, you could imagine that you were permitted to say certain things. Right now, it’s not [like that], you feel that you are forbidden to say one letter about your feelings”.(Interviewee 7)

“When I am with people, I prefer to speak as little as possible and not to express a position, so that whoever is sitting with me—will feel that each one lives in a different world”.(Interviewee 4)

3.4.2. Subtheme 4.2. The Relationships Between Israeli Arab and Jews

“I work in Jewish educational frameworks, and there it is more difficult. When people hear you speaking Arabic, they immediately [mark you] with a red mark…”.(Interviewee 2)

“What frightened me at the beginning of the war was that I work in a hospital… there are both Jews and Arabs… I remember that at the start of the war, Jews frequently confronted us verbally…If the situation had continued this way, I would not have been prepared to continue my work, because I did not want to work in a place where I don’t feel comfortable going there”.(Interviewee 5)

“I hear that the whole issue of relations between Jews and Arabs is especially complicated in a war because Arabs are not able to speak in workplaces. Because if they express their opinions, it will be considered that they think against [their Jewish colleagues], every word is perceived differently and perhaps you will lose your position”.(Interviewee 1)

“I thought, how will I meet my colleagues, Arab and Jewish? Since I’m not a politician, I was afraid to speak about politics… The following day, I couldn’t decide whether to go to work or not. I work in a hospital, and by evening I decided not to go… I had a fear that they would make faces, or they wouldn’t talk to me, or they would turn on me”.(Interviewee 3)

“I started to doubt my ability to go to work and to meet people from other nations… What helped me a little was that the Jews who worked with me at the same workplace left [to join] the army for the emergency call-up order. Perhaps that made it easier for me in this situation, or it is possible that the situation became more difficult because I held a certain position without meeting the other side… Specifically, I avoid going to places like this when they are crowded with Jews. This all affected the period of my pregnancy; it has become much more depressing”.(Interviewee 7)

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. (Ed.) Blossoming and growing in the transition to parenthood. In Pathways and Barriers to Parenthood; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveley, S. Becoming mum: Exploring the emergence and formulation of a mother’s identity during the transition into motherhood. In Childbearing and the Changing Nature of Parenthood: The Contexts, Actors, and Experiences of Having Children; Costa, R.P., Blair, S.L., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; Volume 14, pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, M.L.; Clarke, A.D.; Rigato, S. The mental health crisis of expectant women in the UK: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on prenatal mental health, antenatal attachment and social support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarratano, G.P.; Barcelona, V.; Savage, J.; Harville, E. Mental health and worries of pregnant women living through disaster recovery. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendavid, E.; Boerma, T.; Akseer, N.; Langer, A.; Malembaka, E.B.; Okiro, E.A.; Wise, P.H.; Heft-Neal, S.; Black, R.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet 2021, 397, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Ziv, Y.; Brom, D. Multiple traumas, maternal depression, mother-child relationship, social support, and young children’s behavioral problems. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 892–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim IC, Z.; Tam, W.W.; Chudzicka-Czupała, A.; McIntyre, R.S.; Teopiz, K.M.; Ho, R.C.; Ho, C.S. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress in war-and conflict-afflicted areas: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 978703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpiniello, B. The mental health costs of armed conflicts—A review of systematic reviews conducted on refugees, asylum-seekers and people living in war zones. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A.; Cohen, M.; Azaiza, F. Factors associated with routine screening for the early detection of breast cancer in cultural-ethnic and faith-based communities. Ethn. Health 2019, 24, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O.; Chasson, M.; Abu Sharkia, S.; Weiss, E. Distress and anxiety associated with COVID-19 among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020, 38, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O.; Chasson, M.; Erel-Brodsky, H.; Abu-Sharkia, S.; Skvirsky, V.; Horowitz, E. Contributors to COVID-19-related childbirth anxiety among pregnant women in two pandemic waves. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simhi, M.; Schiff, M.; Pat-Horenczyk, R. Economic disadvantage and depressive symptoms among Arab and Jewish women in Israel: The role of social support and formal services. Ethn. Health 2024, 29, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyamini, I.M.; Shoshana, A. “I wanted to be a bride, not a wife”: Accounts of child marriage in the Bedouin community in Israel. Transcult. Psychiatry 2023, 60, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meler, T. Money, power, and inequality within marriage among Palestinian families in Israel. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 68, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayanni, M. Multiculturalism as covering: On the accommodation of minority religions in Israel. Am. J. Comp. Law 2018, 66, 831–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Crenshaw, K.W.; McCall, L. Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.B.; Pemberton, H.R.; Tonui, B.; Ramos, B. Responding to perinatal health and services using an intersectional framework at times of natural disasters: A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, L.; Mijalevich-Soker, E.; Joffe, E.; Awad-Yasin, M.; Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and war-related concerns among pregnant women: The contribution of self-mastery and intolerance of uncertainty. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Froimovici, M.; O’Rourke, N.; Azbarga, Z.; Okby-Cronin, R.; Salman, L.; Alkatnany, A.; Grotto, I.; Daoud, N. Direct and indirect determinants of prenatal depression among Arab-Bedouin women in Israel: The role of stressful life events and social support. Midwifery 2021, 96, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelöf, K.; Thomas, K.; Almquist-Tangen, G.; Nyström, C.D.; Löf, M. Well-being during pregnancy and the transition to motherhood: An explorative study through the lens of healthcare professionals. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Taken Out of Context? Hamas Backtracks on Senior Official’s Statements Regretting Consequences of 2023 Assault on Israel. FDD. 24 February 2025. Available online: https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2025/02/24/taken-out-of-context-hamas-backtracks-on-senior-officials-statements-regretting-consequences-of-2023-assault-on-israel/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Hatch, S.L.; Dohrenwend, B.P. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: A review of the research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 40, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.L.; Gilman, S.E.; Breslau, J.; Breslau, N.; Koenen, K.C. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreier, H.M.; Bosquet Enlow, M.; Ritz, T.; Coull, B.A.; Gennings, C.; Wright, R.O.; Wright, R.J. Lifetime exposure to traumatic and other stressful life events and hair cortisol in a multi-racial/ethnic sample of pregnant women. Stress 2016, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A.Y.; McCall, L. Intersectionality and social explanation in social science research. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atewologun, D. Intersectionality Theory and Practice. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; 2018; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/business/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.001.0001/acrefore-9780190224851-e-48 (accessed on 27 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Qutteina, Y.; Nasrallah, C.; James-Hawkins, L.; Nur, A.A.; Yount, K.M.; Hennink, M.; Rahim HF, A. Social resources and Arab women’s perinatal mental health: A systematic review. Women Birth 2018, 31, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaby, R.; Peres, H. Between a woman and her fetus: Bedouin women mediators advance the health of pregnant women and babies in their society. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Age | Employment | Mother/Pregnant | Religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | Nurse | Mother to 3-month-old daughter | Muslim |

| 2 | 31 | Educational psychologist | Mother to 3-year-old daughter and 5 months pregnant | Druze |

| 3 | 30 | Human resources director | 5 months pregnant | Muslim |

| 4 | 28 | Teacher | Mother to 7-month-old daughter | Muslim |

| 5 | 33 | Physiotherapist | Mother to 2 children and 9 months pregnant | Muslim |

| 6 | 26 | Lawyer | 8 months pregnant | Muslim |

| 7 | 32 | Physician | 7 months pregnant | Muslim |

| 8 | 28 | Teacher | 8 months pregnant | Muslim |

| 9 | 32 | Nurse | Mother to 2 children and 8 months pregnant | Christian |

| 10 | 25 | Does not work | 9 months pregnant | Muslim |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awad-Yasin, M.; Ring, L.; Mijalevich-Soker, E.; Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. Vulnerability and Complexity: Wartime Experiences of Arab Women During the Perinatal Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040588

Awad-Yasin M, Ring L, Mijalevich-Soker E, Taubman – Ben-Ari O. Vulnerability and Complexity: Wartime Experiences of Arab Women During the Perinatal Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040588

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwad-Yasin, Maram, Lia Ring, Elad Mijalevich-Soker, and Orit Taubman – Ben-Ari. 2025. "Vulnerability and Complexity: Wartime Experiences of Arab Women During the Perinatal Period" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040588

APA StyleAwad-Yasin, M., Ring, L., Mijalevich-Soker, E., & Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. (2025). Vulnerability and Complexity: Wartime Experiences of Arab Women During the Perinatal Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040588