Reconfiguring Rehabilitation Services for Rural South Africans with Disabilities During a Health Emergency: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 and Rehabilitation Services

1.2. Experiences of Rehabilitation Practitioners During COVID-19

1.3. Knowledge Gap in Rural Rehabilitation Services

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

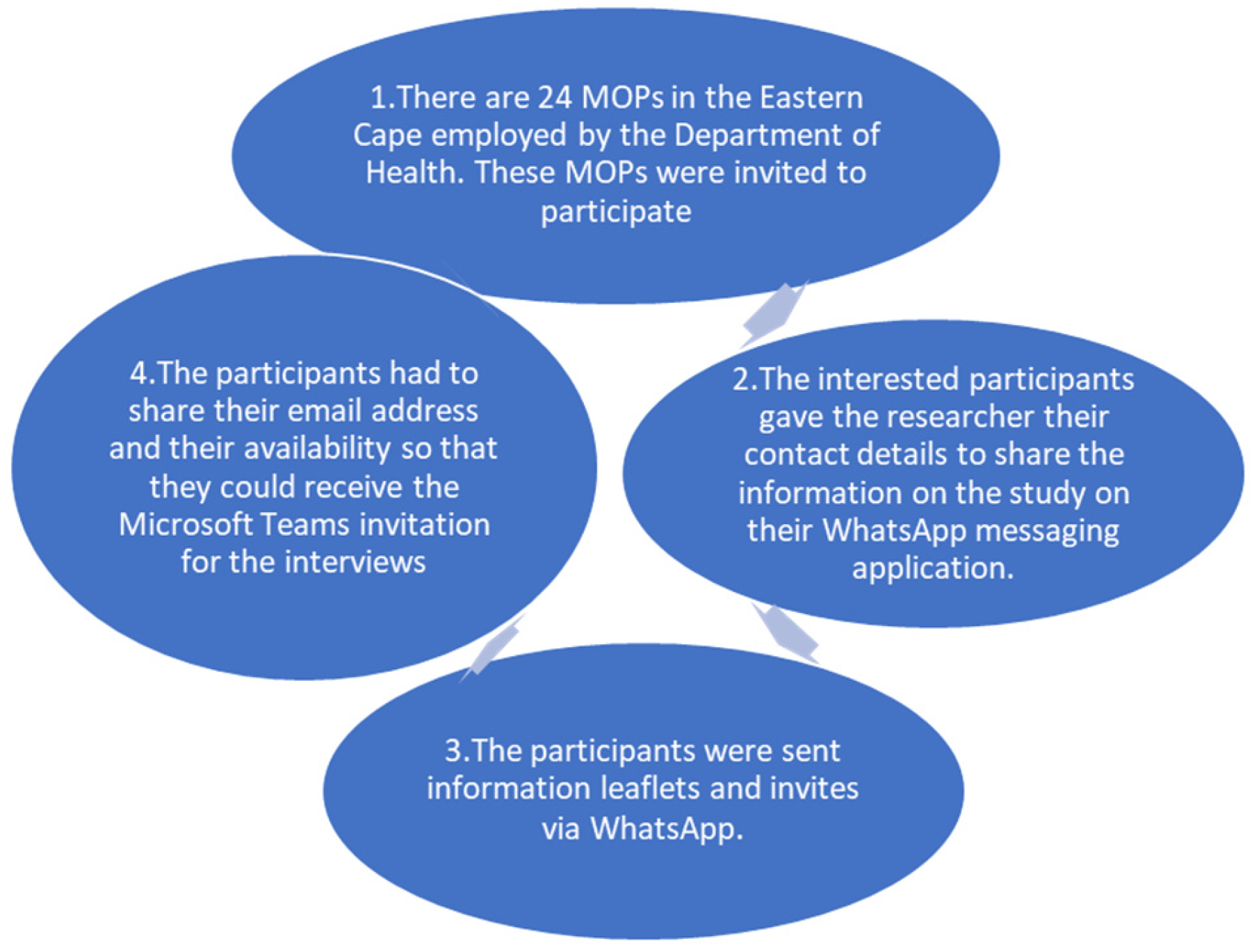

2.2. Study Population and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

- The first author acquainted herself with the data by listening to the audio-visual recordings of each interview on MS Teams. This process was repeated four times while checking against the transcripts for the accuracy of the data with the co-authors. The first author documented her thoughts in the form of notes and stored raw data of all notes, transcripts, and reflective notes.

- The first author sorted and organised the data manually, grouping the data into codes by using tables on Microsoft Word. The codes were informed by words, phrases, and sentences that addressed the research question. These were shared with the co-authors.

- The first author analysed the codes by using a reflexive diary with sub-themes and main themes. Codes were grouped into sub-themes. These sub-themes were grouped into themes. These codes were further compiled in a Microsoft Word document.

- Themes and sub-themes were reviewed and analysed by the co-authors, who were supervisors of the first author.

- The generated themes were then defined and named by all authors.

- The findings were written in the form of themes and sub-themes with explanations supported by verbatim quotes from the participants, as presented in the Results section. The reflexive diary was used to make sense of the data and making notes on interpretation. This helped when writing up the Results and Discussion sections.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

- Beneficence: Beneficence is the moral duty to maximise good and minimise bad [27]. We ensured that participants were well informed about risks that they might be exposed to and ensured that consent was granted at all times. Participants were made aware of the potential data risks that might happen should data be accessed by unauthorized personnel in the event of being hacked. This was mitigated by using pseudo-names on all stored data to protect the identity of the participants. The interviews were also saved in a different system in an encrypted folder.

- Non-Maleficence: All parties involved in the research study, including participants, participating communities, and the larger South African society, should be treated fairly in terms of risks and benefits [27]. Participants were informed about what was required from them and that their human rights would not be violated. Once the interviews were performed, participants were compensated with gift vouchers and data bundles to connect to the internet.

- Autonomy and Dignity: People’s decisions must be treated with respect, and they must be given the opportunity to exercise their right to self-determination [27]. Every participant had the right to express themselves in the interview, without infringement of their rights. We also ensured their privacy by safeguarding Confidentiality.

2.6. Ensuring Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Description of Participants

3.2. Themes Emerging from the Data

3.2.1. Theme 1: Disrupted Access to O&P Services

“No-one knew what we were supposed to do. People in charge were not even aware that the O&P department existed or what we do”.

“The continuation of outreach would have assisted in ensuring accessibility of services to people with disabilities”.

“Most services continued but casting and making new devices were only for those that were urgent”.

“Everything continued as normal like there was nothing new that was put in place to be guided by. So, we had to work as normal”.

“Patients were seen according to the number of patients that are accepted by OOPD [Orthopaedic Out Patient Department]. We receive walk-in patients from that department. We did not have our own schedule so we are relied on them”.

“Services were not halted but patients just did not show up and numbers decreased during this time. Everything was kept close to normal as possible”.

3.2.2. Theme 2: O&P Backlog and Limited Services

“We experienced a heavy backlog and limited assistive devices. Patients would not receive the appropriate rehabilitation services they needed”.

“We could not buy certain materials for patients if the money was redirected to the purchase of PPE. This has resulted in us having a backlog and disadvantaging the patients with disability. It meant that [persons with disabilities] will further not receive treatment and this will negatively affect them”.

“Most services continued, but casting and making new devices were only for those that were urgent. Patients that needed their devices repaired were prioritised during this time. New devices were not issued and this created a long backlog. Orthotic devices were prioritised so that we can avoid contractures. We also continued issuing all off-shelf devices”.

“All services were rendered but a professional was only allowed to see a certain number [of patients] per day in order to reduce the risk of contracting the virus”.

“We were one hundred percent operational. We did manufacture of orthotic and prosthetic devices. The only time we became a bit congested was when a staff member got ill or even staff members’ families got ill then they had to be out of work. But service continued the same”.

“Nothing has changed post COVID-19 but we are trying our level best in decluttering the backlog it has left for us”.

“There was little consideration for persons with disabilities … people could not access our services during this period, increasing the backlog”.

“O&P was an afterthought and we could not buy certain materials for patients if the money was not redirected to the purchase of PPE. This has resulted in us having a backlog and disadvantaging the patients with disability. It meant that persons with disabilities will further not receive treatment and this will negatively affect them”.

“A certain number of patients were taken a day, this was done so as to avoid a huge number of patients coming to the hospital and risk of contracting the virus”.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Safety Measures and Adaptation Control

“We implemented our own infection control measures … like hand sanitisers and social distancing”.

“We had to come up with what we can do or cannot do to make sure that we don’t get infected or infect the patients”.

“Due to small space of work we were instructed as staff members to rotate, and fifty percent of the staff be at home and fifty percent be at work. However, if you are at home, you should consider yourself as someone who is on standby. Should the need arise for you to be at work you should avail yourself. If not, you sign leave. This was to ensure the continuity of the services to the public but at the same time adhere to the rules and guidelines of the pandemic”.

“Staff attended some trainings conducted by infection control manager about the pandemic to be equipped and be ready for any pandemic that might come in the future”.

3.2.4. Theme 4: Lingering Challenges and Gaps

“My concerns were shortage of materials, patients not coming to the hospital for services as told or on appointments, not being able to deliver to patients to our fullest potential because of the fear of the unknown following the pandemic. Even after the pandemic none of the concerns have changed because we are still in the same situation as compared to that time of the pandemic”.

“The COVID-19 pandemic helped give us recognition as essential services and this meant that patients could still access our services regardless of some of the restrictions on services that were rendered during this time”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuper, H.; Banks, L.M.; Bright, T.; Davey, C.; Shakespeare, T. Disability inclusive COVID-19 response: What it is, why it is important and what we can learn from the United Kingdom’s response. Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, E.L.; McKinney, V.; Swartz, L. Access to healthcare for people with disabilities in South Africa: Bad at any time, worse during COVID-19? South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 63, a5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ned, L.; McKinney, E.L.; McKinney, V.; Swartz, L. COVID-19 pandemic and disability: Essential considerations. Soc. Health Sci. 2020, 18, 136–148. Available online: https://unisapressjournals.co.za/index.php/SaHS/article/view/13177 (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Ned, L.; McKinney, E.L.; McKinney, V.; Swartz, L. Experiences of vulnerability of people with disabilities during COVID-19 in South Africa. South Afr. Health Rev. 2022, 24, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwerder, B.; Pokharel, S.; Khadka, K.; Wong, S.; Morrison, J. Understanding how children and young people with disabilities experience COVID-19 and humanitarian emergencies in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Glob. Health Action 2021, 15, 2107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/global-report-on-health-equity-for-persons-with-disabilities (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Banks, L.M.; Davey, C.; Shakespeare, T.; Kuper, H. Disability inclusive responses to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from research on social protection in low-and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. 2019 “General Household Survey”. In Statistics; Government of South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Uys, K.; Casteleijn, D.; Van Niekerk, K.; Balbadur, R.; d’Oliveira, J.; Msimango, H. The impact of COVID-19 on occupational therapy services in Gauteng Province, South Africa: A qualitative study. In South African Health Review: Health Sector Responses to COVID-19; Govender, K., George, G., Padarath, A., Moeti, T., Eds.; Health Systems Trust: Durban, South Africa, 2021; pp. vii–ix. Available online: https://www.hst.org.za/publications/South%20African%20Health%20Reviews/SAHR21_WEB_NoBlank_sm_24022022_OD.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Report 27 August 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Maphumulo, W.; Bhengu, B. Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid. A critical review. Curationis 2019, 42, a1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, K.; Ned, L.; Engelbrecht, M. Disability inclusion and pandemic policymaking in South Africa: A framework analysis. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 26, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalatse, N.; Casteleijn, D.; du Plooy, E.; Msimango, H.; Ramodike, V. Occupational therapists’ perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on their clients in Gauteng, South Africa. South Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 52, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Biljon, H.M.; Van Niekerk, L. Working in the time of COVID-19: Rehabilitation clinicians’ reflections of working in Gauteng’s public healthcare during the pandemic. Afr. J. Disabil. 2022, 11, a889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puli, L.; Layton, N.; Mont, D.; Shae, K.; Calvo, I.; Hill, K.D.; Callaway, L.; Tebbutt, E.; Manlapaz, A.; Groenewegen, I.; et al. Assistive technology provider experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, S.N.; Seedat, J.; Coutts, K.; Kater, K.-A. ‘We are in this together’ Voices of speech-language pathologists working in South African healthcare contexts during level 4 and level 5 lockdown of COVID-19. South Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2021, 68, a792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatya, B.; Khan, F. Rehabilitation response in pandemics. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Biase, S.; Cook, L.; Skelton, D.A.; Witham, M.; Ten Hove, R. The COVID-19 rehabilitation pandemic. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, H.L.; Oh-Park, M.; Cifu, D.X. The war on COVID-19 pandemic: Role of rehabilitation professionals and hospitals. American J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firshman, P.; Hoffman, K.; Rapolthy-Beck, A. Occupational Therapy for COVID-19 Patients in ICU and Beyond; Intensive Care Society: London, UK, 2020; pp. 2–15. Available online: https://ics.ac.uk/resource/occupational-therapy-for-covid-19-patients-in-icu.html (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Balton, S.; Pillay, M.; Armien, R.; Vallabhjee, A.L.; Muller, E.; Heywood, M.J.; van der Linde, J. Lived experiences of South African rehabilitation practitioners during coronavirus disease 2019. Afr. J. Disabil. 2024, 13, a1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlongwane, N.; Ned, L.; McKinney, E.; McKinney, V.; Swartz, L. Experiences of organisations of (or that serve) persons with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdown period in South Africa. Int. J. Ofenvironmental Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; McCabe, C.; Keogh, B.; Brady, A.; McCann, M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adeoye-Olatunde, O.A.; Olenik, N.L. Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Department of Health. Ethics in Health Research Principles, Processes and Structures, 2nd ed; National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2023-04/NHREC-DoH-2015-Ethics-in-Health-Research-Guidelines-1_0.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Fernandes, J.; Donovan-Hall, M. Healthcare professionals’ experiences of primary lower limb prosthetic rehabilitation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Physiotherapy 2024, 123, e249–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutwali, R.; Ross, E. Disparities in physical access and healthcare utilization among adults and without disabilities in South Africa. Disabil Health J. 2019, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.M.; MacLachlan, M.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; Holloway, C.; Austin, V. Developing inclusive and resilient systems: COVID-19 and assistive technology. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 36, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M.G.; Orrù, G.; Littera, R.; Firinu, D.; Chessa, L.; Cossu, G.; Primavera, D.; Del Giacco, S.; Tramontano, E.; Manocchio, N.; et al. Comparing the responses of countries and national health systems to the COVID-19 pandemic: A critical analysis with a case-report series. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 7868–7880. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Municipal District | Years of Experience | Gender | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | OR Tambo District | 3 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 2 | OR Tambo District | 4 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 3 | OR Tambo District | 3 | Female | Grade1 MOP |

| Participant 4 | OR Tambo District | 4 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 5 | OR Tambo District | 3 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 6 | Amathole District | 6 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 7 | Amathole District | 6 | Female | Chief MOP |

| Participant 8 | Amathole District | 5 | Male | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 9 | Amathole District | 5 | Male | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 10 | Sarah Baartman District | 10 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 11 | Sarah Baartman District | 8 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

| Participant 12 | Sarah Baartman District | 4 | Female | Grade 1 MOP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tekula, L.; Engelbrecht, M.; Ned, L. Reconfiguring Rehabilitation Services for Rural South Africans with Disabilities During a Health Emergency: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040567

Tekula L, Engelbrecht M, Ned L. Reconfiguring Rehabilitation Services for Rural South Africans with Disabilities During a Health Emergency: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040567

Chicago/Turabian StyleTekula, Litakazi, Madri Engelbrecht, and Lieketseng Ned. 2025. "Reconfiguring Rehabilitation Services for Rural South Africans with Disabilities During a Health Emergency: A Qualitative Descriptive Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040567

APA StyleTekula, L., Engelbrecht, M., & Ned, L. (2025). Reconfiguring Rehabilitation Services for Rural South Africans with Disabilities During a Health Emergency: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040567