Gain-Framed Text Messages and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Screening Patients: A Brief Report of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

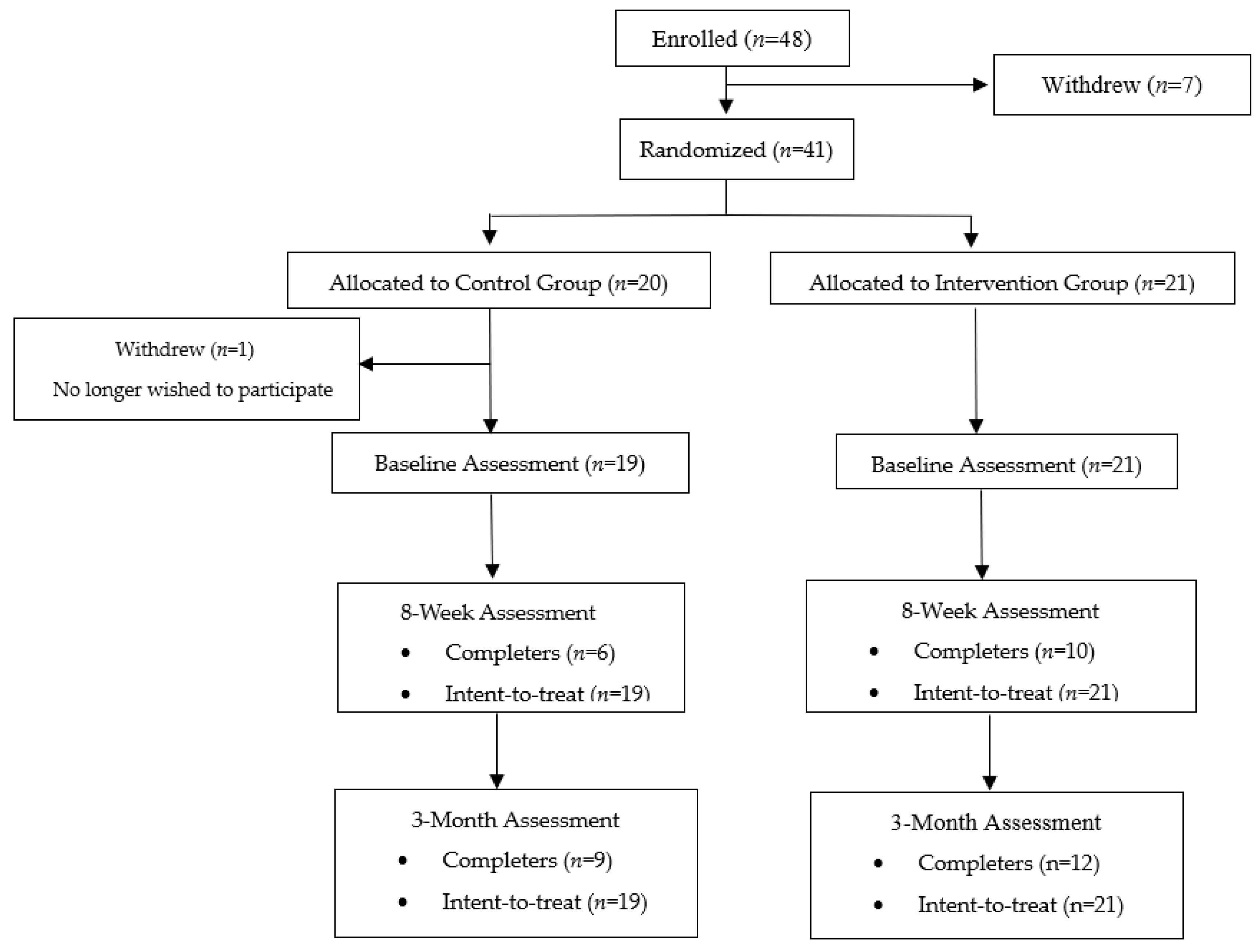

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanner, N.T.; Kanodra, N.M.; Gebregziabher, M.; Payne, E.; Halbert, C.H.; Warren, G.W.; Egede, L.E.; Silvestri, G.A. The association between smoking abstinence and mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.M.; Rothman, A.J.; Almirall, D.; Begnaud, A.; Chiles, C.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Fu, S.S.; Graham, A.L.; Lindgren, B.R.; Melzer, A.C.; et al. Lung cancer screening and smoking cessation clinical trials. SCALE (smoking cessation within the context of lung cancer screening) collaboration. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, K.L.; Dressler, E.V.; Weaver, K.E.; Sutfin, E.L.; Miller, D.P., Jr.; Bellinger, C.; Kittel, C.; Stone, J.R.; Petty, W.J.; Land, S.R.; et al. The optimizing lung screening trial (WF-20817CD): Multicenter randomized effectiveness implementation trial to increase tobacco use cessation for individuals undergoing lung screening. Chest 2023, 164, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.S.; Rothman, A.J.; Vock, D.M.; Lindgren, B.R.; Almirall, D.; Begnaud, A.; Melzer, A.C.; Schertz, K.L.; Branson, M.; Haynes, D.; et al. Optimizing longitudinal tobacco cessation treatment in lung cancer screening: A sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2329903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.L.; Williams, R.M.; Li, T.; Luta, G.; Smith, L.; Davis, K.M.; Stanton, A.C.; Niaura, R.; Abrams, D.; Lobo, T.; et al. A randomized trial of telephone-based smoking cessation treatment in the lung cancer screening setting. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeliadt, S.; Heffner, J.; Coggeshall, S.; Nici, L.; Becker, D.; Klein, D.; Hildie, S.; Feemster, L. A pragmatic randomized trial of proactive smoking cessation support following lung cancer screening. In Proceedings of the Chest 2023, Honolulu, HI, USA, 8–11 October 2023; Volume 164, pp. A6393–A6394. [Google Scholar]

- Rojewski, A.M.; Bailey, S.R.; Bernstein, S.L.; Cooperman, N.A.; Gritz, E.R.; Karam-Hage, M.A.; Piper, M.E.; Rigotti, N.A.; Warren, G.W. Considering systemic barriers to treating tobacco use in clinical settings in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, C.; Knight, R.; Robertson, S.; Whittaker, R.; Edwards, P.; Zhou, W.; Rodgers, A.; Cairns, J.; Kenward, M.G.; Roberts, I. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): A single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A meta-analytic review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toll, B.A.; Martino, S.; Latimer, A.; Salovey, P.; O’Malley, S.; Carlin-Menter, S.; Hopkins, J.; Wu, R.; Celestino, P.; Cummings, K.M. Randomized trial: Quitline specialist training in gain-framed vs. standard-care messages for smoking cessation. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toll, B.A.; O’Malley, S.S.; Katulak, N.A.; Wu, R.; Dubin, J.A.; Latimer, A.; Meandzija, B.; George, T.P.; Jatlow, P.; Cooney, J.L.; et al. Comparing gain-and loss-framed messages for smoking cessation with sustained-release bupropion: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007, 21, 534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, M.J.; Hughes, J.R.; Gray, K.M.; Wahlquist, A.E.; Saladin, M.E.; Alberg, A.J. Nicotine therapy sampling to induce quit attempts among smokers unmotivated to quit: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 1901–1907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jardin, B.F.; Cropsey, K.L.; Wahlquist, A.E.; Gray, K.M.; Silvestri, G.A.; Cummings, K.M.; Carpenter, M.J. Evaluating the effect of access to free medication to quit smoking: A clinical trial testing the role of motivation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 16, 992–999. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, M.C.; McCarthy, E.D.; Jackson, T.C.; Zehner, E.M.; Jorenby, E.D.; Mielke, M.; Smith, S.S.; Guiliani, A.T.; Baker, T.B. Integrating smoking cessation treatment into primary care: An effectiveness study. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roughgarden, K.L.; Toll, B.A.; Tanner, N.T.; Frazier, C.C.; Silvestri, G.A.; Rojewski, A.M. Tobacco treatment specialist training for lung cancer screening providers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.M.; Sobell, L.C.; Sobell, M.B.; Leo, G.I. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.; Ndoen, E.; Borland, R. Smokers’ risk perceptions and misperceptions of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and nicotine replacement therapies. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018, 37, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.E.; Coleman, B.; Tessman, G.K.; Dickinson, D.M. Unpacking smokers’ beliefs about addiction and nicotine: A qualitative study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2017, 31, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall Sample (N = 40) | Intervention Group (n = 21) | Control Group (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Insurance Status a | |||

| Medicare | 17 (42.5%) | 10 (47.6%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| Medicaid | 14 (35.0%) | 7 (33.3%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| Private | 14 (35.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| None | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Other | 4 (10.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 22 (55%) | 12 (57.1%) | 10 (52.6%) |

| Male | 18 (45%) | 9 (42.9%) | 9 (47.4%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 7 (17.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Married | 18 (45.0%) | 11 (52.4%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| Separated | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Divorced | 9 (22.5%) | 5 (23.8%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Widow | 4 (10.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Cohabitating | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race a | |||

| Black or African American | 13 (32.5%) | 5 (23.8%) | 8 (42.1%) |

| White | 27 (67.5%) | 15 (71.4%) | 12 (63.2%) |

| Other | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 40 (100.0%) | 40 (100%) | 40 (100%) |

| Education Level | |||

| Less than high school/GED | 10 (25.0%) | 4 (19.1%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| High school diploma/GED | 13 (32.5%) | 6 (28.6%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| Vocational training | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Associate’s degree/Some college | 11 (27.5%) | 8 (38.1%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 3 (7.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 2 (10.6%) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed full-time | 5 (12.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Employed part-time | 6 (15.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Unemployed or disabled | 18 (45.0%) | 9 (42.9%) | 9 (47.4%) |

| Retired | 10 (25.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Other | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Income (amount per year) | |||

| <USD 8000–USD14,999 | 11 (27.5%) | 5 (23.8%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| USD 15,000–USD 24,999 | 8 (20.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| USD 25,000–USD 34,999 | 5 (12.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| USD 35,000–USD 49,999 | 6 (15.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| USD 50,000–USD 64,999 | 3 (7.5%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| USD 65,000–USD 79,999 | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| USD 80,000–USD 100,000 | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| >USD 100,000 | 3 (7.5%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age in years (Mean, SD) | 64.4 (6.2) | 65.4 (6.1) | 63.4 (6.3) |

| Nicotine dependence (FTND Score; Mean, SD) | 4.3 (1.9) | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.4 (1.7) |

| Cigarettes per day at baseline (Mean, SD) | 14.8 (9.0) | 17.6 (9.42) | 11.8 (7.6) |

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy Product | 2 Weeks n (%) | 4 Weeks n (%) | 6 Weeks n (%) | 8 Weeks n (%) | 12 Weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | |||||

| Patches | 9 (42.9%) | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (52.4%) | 9 (42.9%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| Lozenges | 13 (61.9%) | 9 (42.9%) | 8 (38.1%) | 4 (19.0%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| Gum | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nasal spray | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Control Group | |||||

| Patches | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Lozenges | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gum | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nasal spray | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Question | N (%) |

|---|---|

| The advice that I received via text was easy to understand. | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Somewhat disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Somewhat agree | 0 (0%) |

| Agree | 6 (60.0%) |

| Strongly agree | 4 (40.0%) |

| The text messages were helpful in my attempt to quit smoking. | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 1 (10.0%) |

| Somewhat disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Somewhat agree | 0 (0%) |

| Agree | 7 (70.0%) |

| Strongly agree | 2 (20.0%) |

| I felt the texts were personalized to me. | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (10.0%) |

| Disagree | 2 (20.0%) |

| Somewhat disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0 (0%) |

| Somewhat agree | 0 (0%) |

| Agree | 6 (60.0%) |

| Strongly agree | 1 (10.0%) |

| You received 3 text messages per day. Did you think that this was… | |

| Far too few texts | 0 (0%) |

| Too few texts | 0 (0%) |

| The perfect amount of texts | 9 (90.0%) |

| Too many texts | 1 (10.0%) |

| Far too many texts | 0 (0%) |

| Were you satisfied with the interactive texts? | |

| Not at all satisfied | 1 (10.0%) |

| Slightly satisfied | 0 (0%) |

| Moderately satisfied | 1 (10.0%) |

| Very satisfied | 4 (40.0%) |

| Extremely satisfied | 4 (40.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pebley, K.; Toll, B.A.; Carpenter, M.J.; Silvestri, G.; Rojewski, A.M. Gain-Framed Text Messages and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Screening Patients: A Brief Report of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040543

Pebley K, Toll BA, Carpenter MJ, Silvestri G, Rojewski AM. Gain-Framed Text Messages and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Screening Patients: A Brief Report of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040543

Chicago/Turabian StylePebley, Kinsey, Benjamin A. Toll, Matthew J. Carpenter, Gerard Silvestri, and Alana M. Rojewski. 2025. "Gain-Framed Text Messages and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Screening Patients: A Brief Report of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040543

APA StylePebley, K., Toll, B. A., Carpenter, M. J., Silvestri, G., & Rojewski, A. M. (2025). Gain-Framed Text Messages and Nicotine Replacement Therapy for Smoking Cessation Among Lung Cancer Screening Patients: A Brief Report of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040543