Enhancing Communication Among Patients with Cancer, Caregivers, and Extended Family: Development of a Communication Module

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Narrative Literature Review

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Information Sources

2.1.4. Search Strategy

2.1.5. Selection Process

2.1.6. Data Analysis

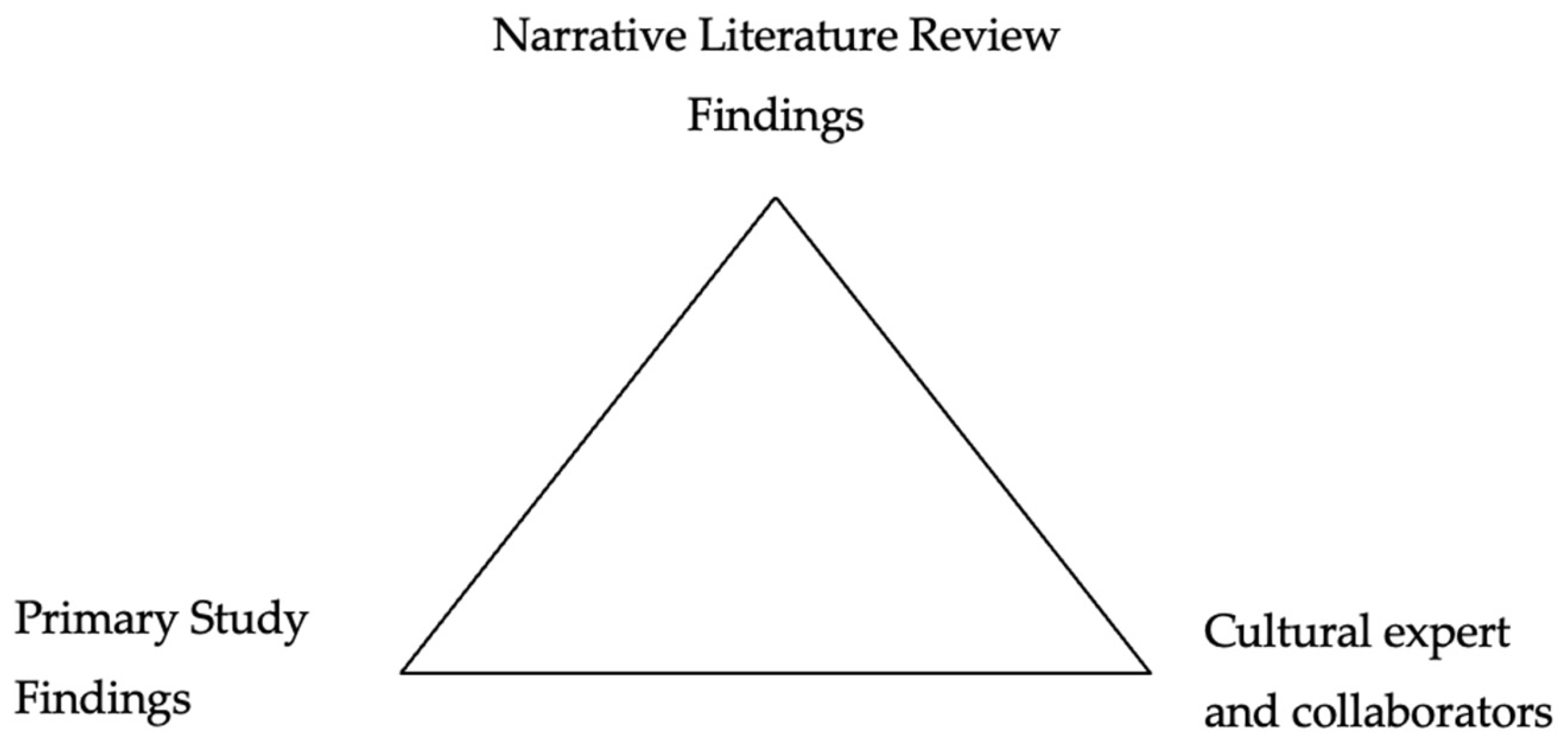

2.2. Data Triangulation

2.2.1. Primary Study

2.2.2. Study and Cultural Expert Background

2.2.3. Data Triangulation Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Narrative Literature Review Findings

3.1.1. Online Sources

| Author (Year) | Title | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Foundation NZ (n.d.) [29] | Communicating to friends & family | Provides support for patients with cancer on how and what they could communicate with others. |

| City of Hope (n.d.) [31] | Communicating with friends and family during and after cancer treatment | The source provides tips or recommendations for communicating a cancer diagnosis to family and friends. |

| Harpham (2021) [27] | Managing communications with family & friends | A column blog that provides insights and tips, such as possible topics, for communicating with family and friends. |

| Mapes (2016) [26] | ‘Coming out’ with cancer: Patients, experts discuss ins and outs of sharing a diagnosis | A personal experience of communicating with family members and provided tips to communicate with them. |

| National Cancer Institute (2015) [30] | Talking to family and friend about your advanced cancer | This source recommends approaching different family members and what the patient should expect from them. |

| Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (n.d.) [28] | Talking to your family about pancreatic cancer | This source provides recommendations for possible topics for communicating with different family members. |

3.1.2. Preliminary Studies

| Author (Year) | Title | Study Type | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ewing et al. (2016) [32] | Sharing news of a lung cancer diagnosis with adult family members and friends: A qualitative study to inform a supportive intervention | Qualitative study | Phase 1: 20 patients, 17 accompanying individuals, 27 healthcare professionals. Phase 2: 24 healthcare professionals and six service users | This study identifies the challenge of sharing bad news and a potential framework to guide the delivery of a supportive intervention tailored to patients’ individual needs. |

| Fisher and Seibaek (2021) [33] | Patient perspectives on relatives and significant others in cancer care: An interview study | Qualitative study | 17 women in gynecological cancer treatment | Relatives represent a unique resource and support to patients. Additionally, neighbors and people who had experienced cancer were an important and valuable support to the patients. |

| Haaksman et al. (2024) [37] | Open communication between patients and relatives about illness & death in advanced cancer—results of the eQuiPe Study | A prospective, longitudinal, multicenter, observational cohort study | 160 bereaved relatives of patients with advanced cancer | Open communication about illness and death between patients and relatives seems to be important, as it is associated with a lower degree of bereavement distress. |

| Peterson et al. (2018) [35] | Patterns of family communication and preferred resources for sharing information among families with a Lynch syndrome diagnosis | Qualitative study | 127 participants: 32 probands (individuals identified with the mutation) and 95 family members | Both probands and family members were most likely to share genetic test results with parents and siblings and least likely to share the results with aunts, uncles, and cousins. |

| Rodríguez et al. (2016) [36] | Family ties: The role of family context in family health history communication about cancer | Correlational study | 472 women | Greater family cohesion, flexibility, and a higher self-efficacy were related to a higher communication frequency and cancer information sharing. |

| Tsuchiya et al. (2022) [34] | Cancer disclosure to friends: Survey on psychological distress and perceived social support provision | Correlational study | 473 patients with cancer | A more significant pre-disclosure distress was associated with being a young adult, being a woman, and delaying disclosure. After disclosing, participants perceived receiving emotional support. |

3.1.3. Randomized Control Trials

3.1.4. Reviews

3.2. Integration of the Findings to Protocol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Tseng, T.-S.; Sutton, V.D.; Price, L. Global Perspectives on Improving Chronic Disease Prevention and Management in Diverse Settings. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2021, 18, E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiakponna, E.C.; Agbomola, J.O.; Ipede, O.; Karakitie, L.O.; Ogunsina, A.J.; Adebayo, K.T.; Tinuoye, M.O. Psychosocial Factors in Chronic Disease Management: Implications for Health Psychology. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Kelly, B. Emotional Dimensions of Chronic Disease. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Adams, R.N.; Mosher, C.E.; Winger, J.G.; Abonour, R.; Kroenke, K. Cancer-Related Loneliness Mediates the Relationships between Social Constraints and Symptoms among Cancer Patients. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Rudzki, G.; Lewandowski, T.; Rudzki, S. The Problems and Needs of Patients Diagnosed with Cancer and Their Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greidanus, M.A.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; de Rijk, A.E.; Tiedtke, C.M.; Dierckx de Casterlé, B.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W.; Tamminga, S.J. Perceived Employer-Related Barriers and Facilitators for Work Participation of Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review of Employers’ and Survivors’ Perspectives. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion, I.V.; Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Marquez, D.X. Examining Cultural Factors That Influence Treatment Decisions: A Pilot Study of Latino Men with Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 2013, 28, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Blasco, N.; Rosario, L.; Shen, M.J. Latino Advanced Cancer Patients’ Prognostic Awareness and Familial Cultural Influences on Advance Care Planning Engagement: A Qualitative Study. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2023, 17, 26323524231193038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCCS El Papel de la Familia en el Bienestar Mental en las Poblaciones Hispanas. Available online: https://hccsphila.org/es/learning-center/el-papel-de-la-familia-en-el-bienestar-mental-en-las-poblaciones-hispanas (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Sabogal, F.; Marín, G.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Marín, B.V.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Hispanic Familism and Acculturation: What Changes and What Doesn’t? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, M.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Afolabi, O.; Koffman, J. Family Involvement in Advance Care Planning for People Living with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Mixed-Methods Review. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laryionava, K.; Hauke, D.; Heußner, P.; Hiddemann, W.; Winkler, E.C. “Often Relatives Are the Key […]”—Family Involvement in Treatment Decision Making in Patients with Advanced Cancer Near the End of Life. Oncologist 2021, 26, e831–e837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario-Ramos, L.; Torres-Marrero, S.; Rivera, T.; Navedo, M.E.; Burgos, R.; Garriga, M.; del Carmen Pacheco, M.; Lopez, B.; Torres, Y.; Torres-Blasco, N. Preparing for Cancer: A Qualitative Study of Hispanic Patient and Caregiver Needs. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/extended-family (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Lewis, F.M.; Cochrane, B.B.; Fletcher, K.A.; Zahlis, E.H.; Shands, M.E.; Gralow, J.R.; Wu, S.M.; Schmitz, K. Helping Her Heal: A Pilot Study of an Educational Counseling Intervention for Spouses of Women with Breast Cancer. Psychooncology 2007, 17, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Blasco, N.; Rosario-Ramos, L.; Arguelles, C.; Torres Marrero, S.; Rivera, T.; Vicente, Z.; Navedo, M.E.; Burgos, R.; Garriga, M.; del Carmen Pacheco, M.; et al. Development of a Community-Based Communication Intervention among Latin Caregivers of Patients Coping with Cancer. Healthcare 2024, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Valencia, M.M. Principles, Scope, and Limitations of the Methodological Triangulation. Investig. Educ. En Enfermeria 2022, 40, e03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-13454-3. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, K.d.S.; Ribeiro, M.C.; de Queiroga, D.E.U.; da Silva, I.A.P.; Ferreira, S.M.S. The Use of Multiple Triangulations as a Validation Strategy in a Qualitative Study. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polite, B.N.; Adams-Campbell, L.L.; Brawley, O.W.; Bickell, N.; Carethers, J.M.; Flowers, C.R.; Foti, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Griggs, J.J.; Lathan, C.S.; et al. Charting the Future of Cancer Health Disparities Research: A Position Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4548–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavel, M.; Sanders, K.D. Community-Engaged Research: Cancer Survivors as Community Researchers. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2014, 9, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkisian, N.; Gerena, M.; Gerstel, N. Extended Family Ties Among Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Whites: Superintegration or Disintegration? Fam. Relat. 2006, 55, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Blasco, N.; Costas Muñiz, R.; Zamore, C.; Porter, L.; Claros, M.; Bernal, G.; Shen, M.J.; Breitbart, W.; Castro, E.M. Cultural Adaptation of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Latino Families: A Protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e045487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Blasco, N.; Costas-Muñiz, R.; Rosario, L.; Porter, L.; Suárez, K.; Peña-Vargas, C.; Toro-Morales, Y.; Shen, M.; Breitbart, W.; Castro-Figueroa, E.M. Psychosocial Intervention Cultural Adaptation for Latinx Patients and Caregivers Coping with Advanced Cancer. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapes, D. “Coming out” with Cancer: Patients, Experts Discuss Ins and Outs of Sharing a Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.fredhutch.org/en/news/center-news/2016/01/coming-out-with-cancer-disclosing-diagnosis.html (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Harpham, W.S. Managing Communications with Family & Friends. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/oncology-times/blog/ViewFromtheOtherSideoftheStethoscope/pages/post.aspx?PostID=29 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Talking to Your Family About Pancreatic Cancer. Available online: https://pancan.org/facing-pancreatic-cancer/living-with-pancreatic-cancer/talking-to-your-family/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Communicating to Friends & Family. Available online: https://www.breastcancerfoundation.org.nz/support/ive-just-been-diagnosed/how-to-communicate-to-friends-and-family (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Talking to Family and Friends About Your Advanced Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/talking (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Communicating with Friends and Family During and After Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cityofhope.org/patients/living-with-cancer/social-concerns-and-relationships/communicating-with-friends-and-family (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Ewing, G.; Ngwenya, N.; Benson, J.; Gilligan, D.; Bailey, S.; Seymour, J.; Farquhar, M. Sharing News of a Lung Cancer Diagnosis with Adult Family Members and Friends: A Qualitative Study to Inform a Supportive Intervention. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.; Seibaek, L. Patient Perspectives on Relatives and Significant Others in Cancer Care: An Interview Study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 52, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Adachi, K.; Kumagai, K.; Kondo, N.; Kimata, A. Cancer Disclosure to Friends: Survey on Psychological Distress and Perceived Social Support Provision. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.; Koptiuch, C.; Wu, Y.P.; Mooney, R.; Elrick, A.; Szczotka, K.; Keener, M.; Pappas, L.; Kanth, P.; Soisson, A.; et al. Patterns of Family Communication and Preferred Resources for Sharing Information among Families with a Lynch Syndrome Diagnosis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.M.; Corona, R.; Bodurtha, J.N.; Quillin, J.M. Family Ties: The Role of Family Context in Family Health History Communication About Cancer. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaksman, M.; Ham, L.; Brom, L.; Baars, A.; Van Basten, J.-P.; Van Den Borne, B.E.E.M.; Hendriks, M.P.; De Jong, W.K.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Van Lindert, A.S.R.; et al. Open Communication between Patients and Relatives about Illness & Death in Advanced Cancer—Results of the eQuiPe Study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodurtha, J.N.; McClish, D.; Gyure, M.; Corona, R.; Krist, A.H.; Rodríguez, V.M.; Maibauer, A.M.; Borzelleca, J.; Bowen, D.J.; Quillin, J.M. The KinFact Intervention—A Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Family Communication About Cancer History. J. Womens Health 2014, 23, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiquelho, R.; Neves, S.; Mendes, Á.; Relvas, A.P.; Sousa, L. proFamilies: A Psycho-Educational Multi-Family Group Intervention for Cancer Patients and Their Families. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.L. Family Communication and Decision Making at the End of Life: A Literature Review. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, Q.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. Communication Needs of Cancer Patients and/or Caregivers: A Critical Literature Review. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, e7432849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandhyala, S.; Kumar, N. Everyday Assertiveness and Its Significance for Overall Mental Well-Being. Univers. J. Public Health 2024, 12, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griner, D.; Smith, T.B. Culturally Adapted Mental Health Intervention: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2006, 43, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama Hall, G.C.; Ibaraki, A.Y.; Huang, E.R.; Marti, C.N.; Stice, E. A Meta-Analysis of Cultural Adaptations of Psychological Interventions. Behav. Ther. 2016, 47, 993–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Cook, P.; Xu, S.; Ranzinger, L.H.; Conklin, J.L.; Alfahad, A.A.S.; Ping, Y.; Shieh, K.; Barroso, S.; Villegas, N.; et al. Family-Based Psychosocial Interventions for Adult Latino Patients with Cancer and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1052229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.L.; Mathews, H.F.; Moye, J.P.; Congema, M.R.; Hoffman, S.J.; Murrieta, K.M.; Johnson, L.A. Four Kinds of Hard: An Understanding of Cancer and Death among Latino Community Leaders. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2021, 8, 23333936211003557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M.; Castro, F.G.; Strycker, L.A.; Toobert, D.J. Cultural Adaptations of Behavioral Health Interventions: A Progress Report. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, F.F.; Booth, J.M. Cultural Adaptation of Interventions in Real Practice Settings. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2015, 25, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Title | Type of Study | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodurtha et al. (2014) [38] | The KinFact intervention: A randomized controlled trial to increase family communication about cancer history. | RCT | 490 women; 245 per group | The KinFact intervention successfully promoted family communication about cancer risk by educating women to enhance their communication skills surrounding family history. |

| Chiquelho et al. (2011) [39] | Pro families: a psycho-educational multifamily group interventions for cancer patients and their families. | Quasi-experimental study | 57 participants from 19 families, divided into five groups | The program responds to the patients’ and families’ needs, prevents an increase in the patient’s level of psychosocial maladjustment, promotes an adequate level of family cohesion, and diminishes the perceived stress of patients and family members. |

| Author (Year) | Title | Type of Study | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kishino et al. (2022) [12] | Family involvement in advance care planning for people living with advanced cancer: A systematic mixed-methods review | Systematic mixed-method review | 14 articles | This review identified individuals’ and family members’ perceptions concerning family involvement in advance care planning and presented components for a family-integrated advance care planning intervention. |

| Wallace (2014) [40] | Family communication and decision making at the end of life: A literature review | Narrative literature review | This review did not include the sample size. | Family members’ communication is crucial during end-of-life care. |

| Communication Strategies | Content | Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt list Delegating Methods of telling others Priority list Seeking support Using informational material Training and educating Booklet Practicing | Learn what to say | We included possible topics (e.g., disclosing the cancer diagnosis, talking about the prognosis of the illness, treatment and symptoms, and sharing emotions and thoughts) and strategies (e.g., delegating, considering the appropriate methods for delivering information, and creating a priority list of family members) to guide the patient and caregiver on what to communicate to extended family. |

| Active listener: Patience Honesty Active speaker: Patience Honesty Training and educating Booklet Practicing | Improve general communication | We included guidelines on general assertive communication skills as a speaker and listener. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Marrero, S.D.; Argüelles-Berrios, C.; Rivera-Torres, N.; Rosario-Ramos, L.; De Lahongrais-Lamboy, A.; Torres-Blasco, N. Enhancing Communication Among Patients with Cancer, Caregivers, and Extended Family: Development of a Communication Module. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040541

Torres-Marrero SD, Argüelles-Berrios C, Rivera-Torres N, Rosario-Ramos L, De Lahongrais-Lamboy A, Torres-Blasco N. Enhancing Communication Among Patients with Cancer, Caregivers, and Extended Family: Development of a Communication Module. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040541

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Marrero, Stephanie D., Carled Argüelles-Berrios, Ninoshka Rivera-Torres, Lianel Rosario-Ramos, Alondra De Lahongrais-Lamboy, and Normarie Torres-Blasco. 2025. "Enhancing Communication Among Patients with Cancer, Caregivers, and Extended Family: Development of a Communication Module" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040541

APA StyleTorres-Marrero, S. D., Argüelles-Berrios, C., Rivera-Torres, N., Rosario-Ramos, L., De Lahongrais-Lamboy, A., & Torres-Blasco, N. (2025). Enhancing Communication Among Patients with Cancer, Caregivers, and Extended Family: Development of a Communication Module. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040541