A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Countries with Highest and Lowest Levels of Discrimination

3.2. Geographic Patterns of Discrimination

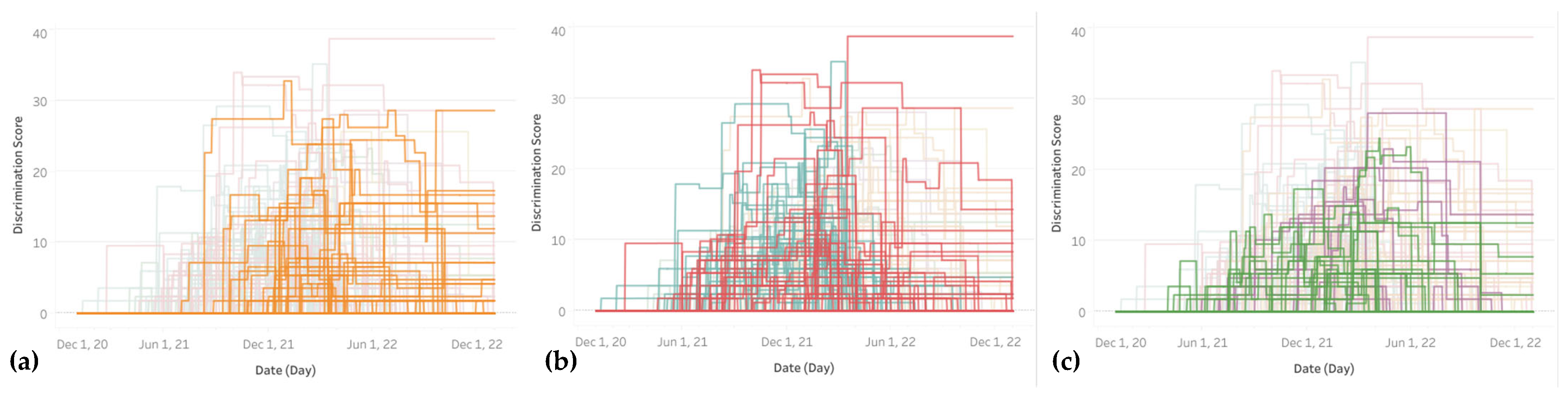

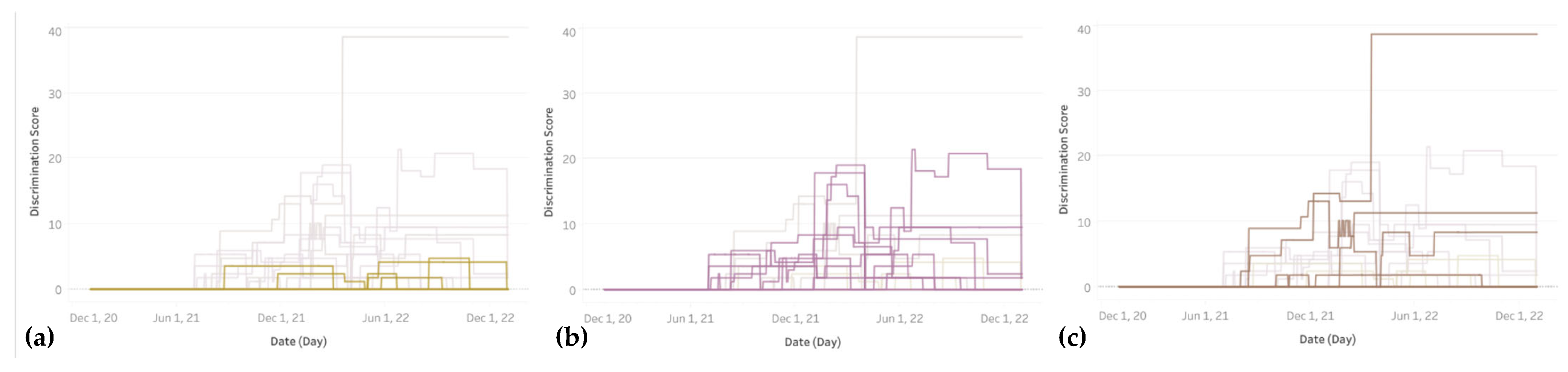

3.3. Timeline of Discrimination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alwan, N.A.; Burgess, R.A.; Ashworth, S.; Beale, R.; Bhadelia, N.; Bogaert, D.; Dowd, J.; Eckerle, I.; Goldman, L.R.; Greenhalgh, T.; et al. Scientific consensus on the COVID-19 pandemic: We need to act now. Lancet 2020, 396, e71–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine. 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201124234740/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/vaccine-benefits.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—4 September 2020. 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200906210508/https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---4-september-2020 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- United Nations. UN Chief: Global Vaccination Plan Is ‘Only Way out’ of the Pandemic|UN News. 30 November 2021. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1106792 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Shrotri, M.; Swinnen, T.; Kampmann, B.; Parker, E.P.K. An interactive website tracking COVID-19 vaccine development. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e590–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, A. Rules for Operating at Warp Speed. Issues Sci. Technol. 2022, 38, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Blake, E.; Tatlow, H.; Andretti, B.; Boby, T.; Green, K.; Hale, T.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Pott, A.; Wade, A.; et al. A panel dataset of COVID-19 vaccination policies in 185 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Kingori, P. No Jab, No Job? Ethical Issues in Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, M. Keeping you informed during negotiations. Br. Columbia Med. J. 2021, 63, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, O.; Rinner, C. Elements of Propaganda in the Western World’s Political, Public Health, and Media Narratives of 2020–2022. In The COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Challenges and Considerations; Egel, E., Patton, C., Eds.; Ethics International Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 78–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chaufan, C. ‘You Are Not a Horse’: Medicalization, Social Control, and Academic Discourse in the COVID-19 Era. In Controversies in the Pandemic; Varon, J., Marik, P.E., Rendell, M., Iglesias, J., de Souza, C., Prabhudesai, P., Eds.; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2024; pp. 60–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bardosh, K.; de Gur-Arie, R.F.A.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime Minister of Canada. Prime Minister Announces Mandatory Vaccination for the Federal Workforce and Federally Regulated Transportation Sectors. 6 October 2021. Available online: https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2021/10/06/prime-minister-announces-mandatory-vaccination-federal-workforce-and (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Backgrounder: Government of Canada Suspends Mandatory Vaccination for Federal Employees [Backgrounders]. 14 June 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/news/2022/06/backgrounder-government-of-canada-suspends-mandatory-vaccination-for-federal-employees.html (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. Vaccination Policies and Human Rights: Frequently Asked Questions for Employers and Employees. 21 October 2021. Available online: https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/resources/vaccination-policies-and-human-rights-frequently-asked-questions-employers-and-employees (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Canadian Human Rights Commission. What is Discrimination? 17 November 2021. Available online: https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/about-human-rights/what-discrimination (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Jean-Jacques, M.; Bauchner, H. Vaccine Distribution-Equity Left Behind? JAMA 2021, 325, 829–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.A.; Mermin-Bunnell, K.M. The ethics of COVID-19 vaccine distribution. J. Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, A.R.; Lockhart, S.H.; Shen, Z.; Azar, K.M.J. Measuring and Promoting SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Equity: Development of a COVID-19 Vaccine Equity Index. Health Equity 2021, 5, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Chattu, V.K. Prioritizing “equity” in COVID-19 vaccine distribution through Global Health Diplomacy. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Najeeb, H.; Moeed, A.; Naeem, U.; Asghar, M.S.; Chughtai, N.U.; Yousaf, Z.; Seboka, B.T.; Ullah, I.; Lin, C.-Y.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 770985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N.; McDonald, J.; Heredia, C. The Risk-Benefit Balance in the COVID-19 “Vaccine Hesitancy” Literature: An Umbrella Review Protocol. Int. J. Vaccine Theory Pract. Res. 2022, 2, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, D.; Germán Roux, A.; Dressen, B. The coverage of medical injuries in company trial informed consent forms. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N. Is resistance to COVID-19 vaccination a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry of vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 688–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bîrsanu, S.-E.; Plaiasu, M.C.; Nanu, C.A. Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management. Vaccines 2022, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, M. Ethics of vaccine refusal. J. Med. Ethics 2022, 48, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. COVID-19: Stigmatising the unvaccinated is not justified. Lancet 2021, 398, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watteel, R.N. Fisman’s Fraud: The Rise of Canadian Hate Science; Indigo; Rainsong Books: Woodinville, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, J.; Savulescu, J.; Brown RC, H.; Wilkinson, D. The unnaturalistic fallacy: COVID-19 vaccine mandates should not discriminate against natural immunity. J. Med. Ethics 2022, 48, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinner, C. Pandemic Open Data: Blessing or Curse? In New Trends and Challenges in Open Data; Kakulapati, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graso, M.; Aquino, K.; Chen, F.X.; Bardosh, K. Blaming the unvaccinated during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of political ideology and risk perceptions in the USA. J. Med. Ethics 2024, 50, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, A.; Jørgensen, F.; Petersen, M. Discriminatory attitudes against unvaccinated people during the pandemic. Nature 2022, 613, 7945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, A. On the Scapegoating of the Unvaccinated: A Media Analysis of Political Propaganda During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kritische Gesellschaftsforschung [Critical Society Studies]. 2022. Available online: https://www.criticalsocietystudies.com/Journal/Article/59/15 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Verkerk, R.; Kathrada, N.; Plothe, C.; Lindley, K. Self-Selected COVID-19 “Unvaccinated” Cohort Reports Favorable Health Outcomes and Unjustified Discrimination in Global Survey. Int. J. Vaccine Theory Pract. Res. 2022, 2, 321–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maras, M.-H.; O’Brien, W. Discrimination, stigmatization, and surveillance: COVID-19 and social sorting. Inf. Commun. Technol. Law 2022, 32, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, L.F.; Begley, A. COVID-19 vaccination requirements for Ireland’s healthcare students. Crit. Soc. Policy 2023, 43, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstner, K. Solidarity and Political Narratives in Crises—Responses to Deviant Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 14, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstner, K. After Two Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: Communication about Unvaccinated Individuals and Possible Social Consequences. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2023, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstner, K. Facing the unvaccinated: Emotions, stereotypes, and the desire for punishment during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Rom. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Smith, M.J.; Emanuel, E. Learning from five bad arguments against mandatory vaccination. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3301–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktionary. Discrimination. In Wiktionary, the Free Dictionary. 2024. Available online: https://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=discrimination&oldid=78565217 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19 (Working Paper, Version 15 BSG-WP-2020/032). 2023. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/BSG-WP-2020-032-v15.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- OxCGRT. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Data Repository [Computer Software]. Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-dataset (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; et al. Our World in Data, COVID-19: Stringency Index. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-stringency-index (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Roser, M. What is the COVID-19 Stringency Index? Our World in Data. 2021. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/metrics-explained-covid19-stringency-index (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Gouvy, C.; Chalton, A. France: Thousands Protest Against Vaccination, COVID-19 Passes. CTV News. 17 July 2021. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220516062148/https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/france-thousands-protest-against-vaccination-covid-19-passes-1.5513214 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Bermingham, P. Macron Ties French Vaccine Passports to Booster Shots. Politico. 9 November 2021. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/france-ties-seniors-vaccine-passports-to-booster-shots/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Natiqqizi, U. COVID Vaccination to Become Virtually Compulsory in Azerbaijan. Eurasianet. 29 July 2022. Available online: https://eurasianet.org/covid-vaccination-to-become-virtually-compulsory-in-azerbaijan (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Shahzad, A. Threats of Cellphone Blocks, Work Bans Boost Pakistan’s Vaccination Rate. Reuters, Asia Pacific. 5 August 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/threats-cellphone-blocks-work-bans-boost-pakistans-vaccination-rate-2021-08-05/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Tidiane Diop, C.A. Pandemic in the Land of Ta Thousand Hills: Rwanda and COVID-19. The Munk School, University of Toronto. 10 January 2020. Available online: https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/research/pandemic-land-thousand-hills-rwanda-and-covid-19 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Bariyo, N. In Some African Nations, Armed Police Enforce COVID-19 Vaccinations: Vaccines are Becoming More Available but Public Wariness of the Shots Poses a Major Hurdle to Inoculation. Wall Street Journal. 28 February 2022. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-some-african-nations-armed-police-enforce-covid-19-vaccinations-11646056306 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ngarambe, A.; Steinwehr, U. Rwandans Report Being Forcibly Vaccinated. Deutsche Welle. 18 January 2022. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/rwanda-forcibly-vaccinating-people-against-covid-victims-say/a-60413978 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Africanews Democratic Republic of Congo: Rwandans Escaping COVID-19 Vaccination Deported. 2022. Available online: https://www.africanews.com/2022/01/13/drc-rwandans-escaping-covid-19-vaccination-deported/) (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Zhu, K.-W. Conflict between freedom and health in the COVID-19 pandemic: An appraisal of China’s zero-COVID-19 policy (13:1548). F1000Research 2024, 13, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Coronavirus in Tanzania: The Country That’s Rejecting the Vaccine. BBC News. 6 February 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55900680 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Mfinanga, S.G.; Gatei, W.; Tinuga, F.; Mwengee, W.M.; Yoti, Z.; Kapologwe, N.; Nagu, T.; Swaminathan, M.; Makubi, A. Tanzania’s COVID-19 vaccination strategy: Lessons, learning, and execution. Lancet 2023, 401, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, M.C. For the Greater Good? The Devastating Ripple Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Balancing the Rights of the Individual with the “Common Good”—Ethical and Policy Frameworks for COVID-19 Pandemic Management. In The COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethical Challenges and Considerations; Egel, E., Patton, C., Eds.; Ethics International Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Public Health Ethics Framework: A Guide for Use in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse/ethics-framework-guide-use-response-covid-19-pandemic.html (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 and Mandatory Vaccination: Ethical Considerations. Policy Brief Prepared by the WHO COVID-19 Ethics and Governance Working Group, Dated 30 May 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354585/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policy-brief-Mandatory-vaccination-2022.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N.; Moncrieffe, R. COVID-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: A cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. J. Public Health Emerg. 2024, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.T.; Serhan, M.; Mithani, S.S.; Smith, D.; Ang, J.; Thomas, M.; Wilson, K. The barriers, facilitators and association of vaccine certificates on COVID-19 vaccine uptake: A scoping review. Glob. Health 2023, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Differentiation Based on Vaccination Status | Coding Values | Flag Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 School closing (schools and universities) | Yes | 0—no measures 1—recommend closing or open with alterations 2—require closing some 3—require closing all | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C2 Workplace closing | Yes | 0—no measures 1—recommend closing or open with alterations 2—require closing for some 3—require closing for all—but—essential workplaces (e.g., grocery stores, doctors) | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C3 Cancel public events | Yes | 0–no measures 1—recommend cancelling 2—require cancelling | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C4 Restrictions on gathering size | Yes | 0—no restrictions 1—restrictions on very large gatherings > 1000 2—restrictions on gatherings > 100 3—restrictions on gatherings > 10 4—restrictions on gatherings of 10 people or less | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C5 Close public transport | Yes | 0—no measures 1—recommend closing (or significantly reduce) 2—require closing | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C6 Stay-at-home requirements | Yes | 0—no measures 1—recommend not leaving house 2—require not leaving house with exceptions for daily exercise, grocery shopping, and ’essential’ trips 3—require not leaving house with minimal exceptions (e.g., allowed to leave once a week, or only one person can leave at a time, etc.) | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C7 Restrictions on internal movement (between cities/regions) | Yes | 0—no measures 1—recommend not to travel 2—restrictions in place | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| C8 Restrictions on international travel (for foreign travellers, not citizens) | Yes | 0—no restrictions 1—screening arrivals 2—quarantine arrivals from some or all regions 3—ban arrivals from some regions 4—ban on all regions | |

| H1 Public information campaign | No | 0—no COVID-19 public information campaign 1—public officials urging caution 2—coordinated public information campaign | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| H2 Testing policy (access to tests) | No | 0—no testing policy 1—testing only those with symptoms AND specific criteria 2—testing of anyone with symptoms 3—open public testing | |

| H3 Contact tracing | No | 0—no contact tracing 1—limited 2—comprehensive | |

| H6 Facial coverings | Yes | 0—No policy 1—Recommended 2—Required in some shared/public spaces 3—Required in all shared/public spaces 4—Required outside the home at all times | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| H7 Vaccination Policy | No | 0—No availability 1—Availability for 1 of these 3 groups: key workers, clinically vulnerable, elderly 2—Availability for 2 of the groups 3—Availability for all 3 groups 4—Availability for all three groups plus more 5—Universal availability | 0—At cost to individual (or funded by NGO, insurance, or partially government-funded) 1—No or minimal cost to individual (gov’t-funded or subsidized) |

| H8 Protection of elderly people | Yes | 0—no measures 1—Recommended isolation, hygiene, and visitor restriction measures in LTCFs and/or elderly people to stay at home 2—Narrow restrictions for isolation, hygiene in LTCFs, some limitations on external visitors and/or restrictions protecting elderly people at home 3—Extensive restrictions for isolation and hygiene in LTCFs, all non-essential external visitors prohibited, and/or all elderly people required to stay at home and not leave the home with minimal exceptions, and receive no external visitors | 0—targeted to specific region 1—across whole country |

| Rank (Top 10) | Average Discrimination Score | Maximum Discrimination Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azerbaijan | 18.70 | Pakistan | 38.69 |

| 2 | Pakistan | 18.22 | France | 35.12 |

| 3 | Rwanda | 12.37 | Azerbaijan | 33.93 |

| 4 | Fiji | 11.31 | Saudi Arabia | 33.34 |

| 5 | Morocco | 10.58 | Cape Verde | 32.73 |

| 6 | Cape Verde | 10.53 | Rwanda | 28.57 |

| 7 | Saudi Arabia | 10.40 | Ecuador | 27.98 |

| 8 | Argentina | 9.86 | Turkey | 27.97 |

| 9 | Sierra Leone | 9.52 | Kosovo | 27.38 |

| 10 | Chile | 9.28 | Oman | 26.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rinner, C.; Uda, M.; Manwell, L. A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040467

Rinner C, Uda M, Manwell L. A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040467

Chicago/Turabian StyleRinner, Claus, Mariko Uda, and Laurie Manwell. 2025. "A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040467

APA StyleRinner, C., Uda, M., & Manwell, L. (2025). A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040467